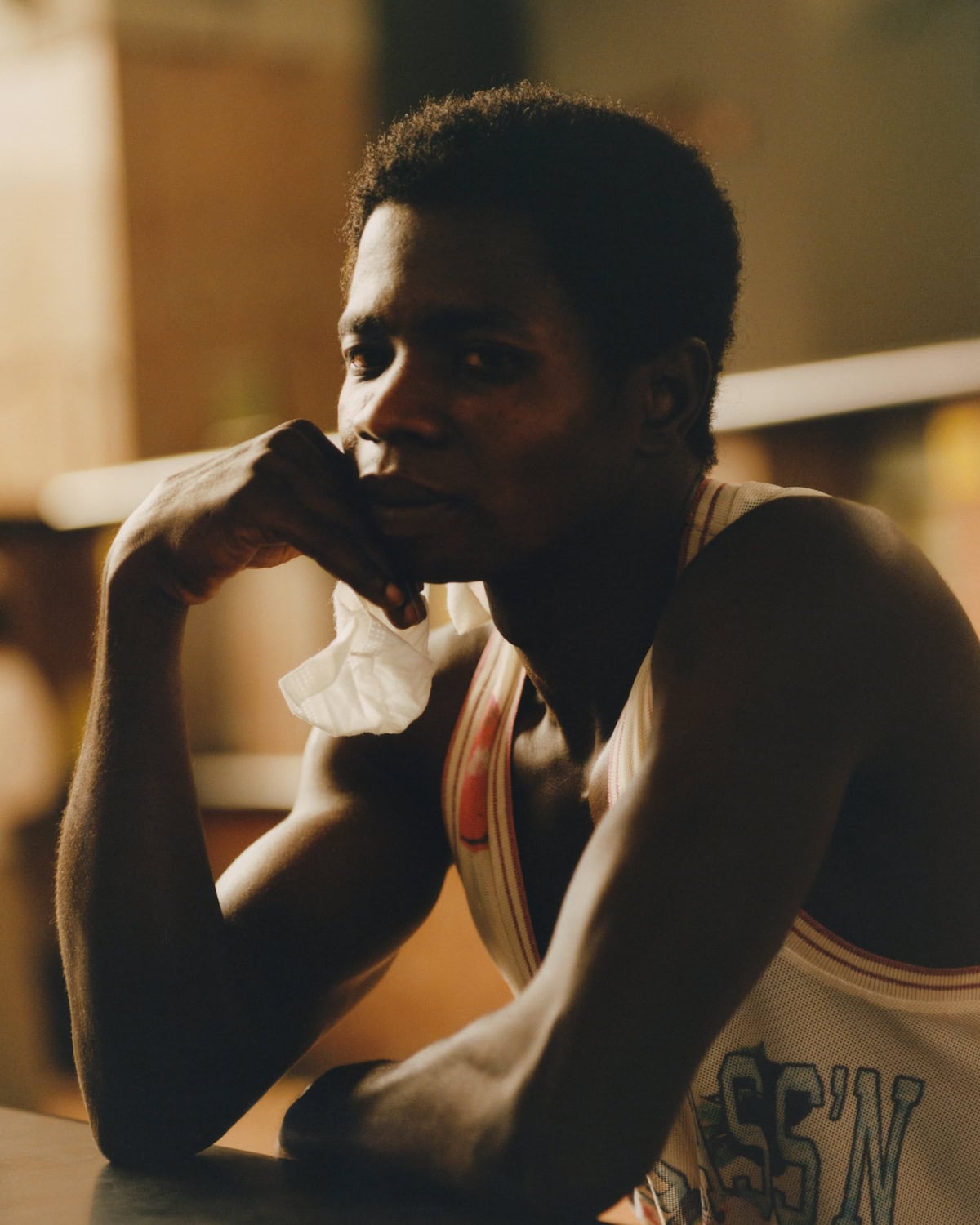

The beams of light are peeking through a grand semicircular window and illuminating the motes of dust. I am in Palermo. The stripped classicism of its main post office, while majestic, takes you back to Italy’s troubled past as you wait in a never-ending queue. All of a sudden, my view is blocked. It takes a few seconds for my eyes to adjust to the darkness before I finally see a tall man. The light wraps around his silhouette like a gentle, warm blanket. I ask, “Can I take your portrait?”. We start chatting and our conversation eventually becomes an inspiration for the journey that follows.

The sea, like a wet canvas, reflects the sun’s amber light. I stare at it through my aeroplane window until a tide picks up the sun’s rays and the light finds its way through the sparsely scattered little clouds. It shines straight into my eyes leaving me completely blind but equally mesmerised for a few seconds. I am heading south to the tiny island of Lampedusa.

The main town. Crowds of tourists. As if the temperature could not be more hellish, the stifling concrete emits even more heat. There really is no doubt that you are closer to North Africa than to the Italian mainland. Docked at the far end of the marina are three boats submerged to the point where they could sink within a matter of seconds. You can still see the clothes of the people who have arrived in them, strewn around and completely untouched. The view is heartbreaking, yet strangely, there is a certain sense of relief to it. Not everyone who takes that dangerous route makes it alive but they did.

Hidden from the sight of tourists and tucked away in the hills, is the “Hotspot” to which migrants are transported after their arrival. There, they undergo identification procedures and await a decision on their future. If their reason for crossing the sea does not meet official standards, they will more likely be deported. For instance, fleeing merciless persecution based on sexual orientation is not enough. If one has come from a part of the world to which the costs of deportation are relatively low, such as most parts of North Africa, they will be returned. Those hailing from more remote lands tend to find more luck, as the authorities are usually unwilling to cover the high costs of their deportation and instead choose to grant asylum.

Watching the Hotspot from afar, you can truly see how vast the diversity among the migrants is. They have come from the Middle East, virtually all parts of Africa and even corners of the globe as remote Southeast Asia. Some may flee famine, some war, but they have one thing in common—their land, in most cases still less than a century ago, used to be a Western colony.

In 2020, the Hotspot authorities took pride in erecting a new building which provides room for over 300 people, rather than 192. Many require urgent medical care, and they still arrive in numbers that vastly exceed the camp’s current capacity. It all could have been resolved much earlier, considering how little money it costs the European Union or Italy alone (even taking their internal struggles into account) to provide decent temporary shelter for those making dangerous sea crossings. And that is regardless of whether the migrants would eventually be deported or not. In fact, a wealthy individual could solve the matter single-handedly. Clearly though, permission is required and the reluctance to fully address this issue persists.

The island is truly tiny. So tiny, that at times you are able to see both shores simultaneously. As you walk further west, the busy beaches turn into steep, desolate cliffs surrounded by crystalline waters. The landscape becomes barren and the absence of virtually all the things that make you think of life creates an impression that there is just you, the breeze that gently caresses your skin and the vastness of the sea. But even the sea seems too distant and abstract to be associated with life. You are so high above the surface of the water that the tides merge together and before your eyes, there is just the colour blue in its simplest form, devoid of details.

My stay on Lampedusa slowly comes to an end. I finally manage to break through the old military zone to reach the island’s most remote, completely uninhabited part. As I clamber up the last hill, dozens of corroding boats stranded in the dry soil emerge from the horizon. Aware that I am trespassing, I approach slowly. Inside them, you will find all kinds of objects that were brought on board: cutlery, first aid kits, a broken satellite phone, life vests. Though what truly catches your eye, are the water bottles. So many water bottles, many still half-full—a reminder that what you are seeing is not a relic of the haunted past but a current reality.

The sun is setting. I rush to reach the end of the island and rest on the edge of the cliff. Before it disappears completely, I take the last picture. What a bizarre experience and what a place. An island tinged with such suffering but surrounded by an aura so pure and so serene.