There is a specific vibration, like a mad restlessness, that creeps into the bodies of those who pass through Venice during the Biennale openings. It is concentrated in the grimaces and the rhythm of the steps, in the number of full glasses and the squeaking of the platforms at the piers. It is condensed into the line of people waiting for taxis at the water gates and the bodyguards of foreign ministers. Everything sounds like a schizophrenic ballet of bewildered tokens, dazzling in their shiny suits. You breathe an atavistic fear of being excluded from the world; all those inconsistent gestures and the frenzy of these days seem to tell of the fear of not being able to access the party: you have to move quickly to reach another place, another event, another opening. And it is better to lengthen the pace, but without spilling the cocktail.

And then it rains. People pile up under the terraces and under the porches, where their hair and make-up get ruined. It’s a bit grotesque, but above all, it’s fun to see the irritation on the faces of passers-by: all that effort for nothing.

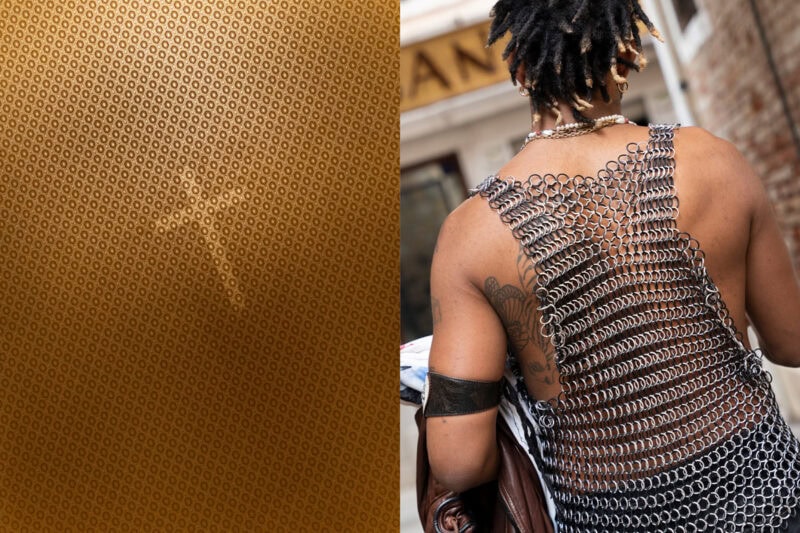

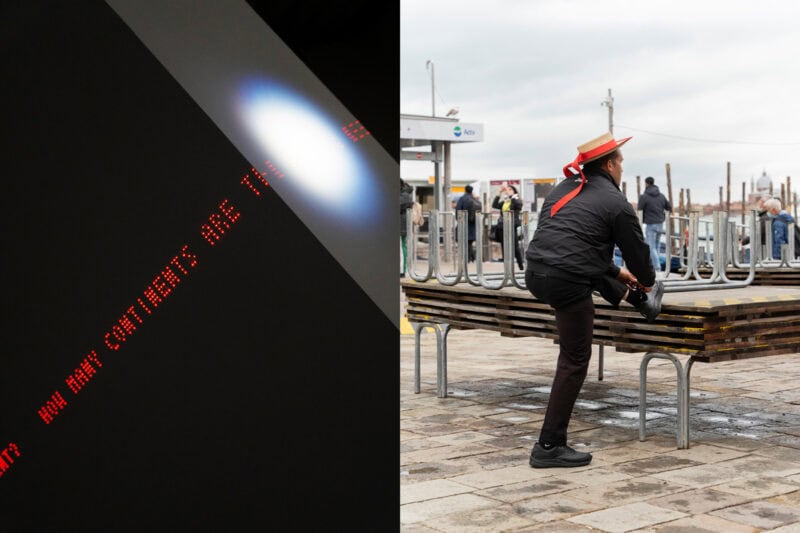

But beyond the inclement weather and the pressure of the queues, there is something else. It is precisely in the excitement of movement and the rush to the aperitifs that we perceive a common desire—perhaps unconscious—to transform oneself. These days Venice seems to give life to a comédie humaine, whose paradoxical traits inform us of a subterranean desire to become something other than oneself; as in a frenetic spectacle, people take on unusual and fantastic forms. Insects and feathered snakes, panthers, and aliens populate the calli and the city is deformed under the restless gaze of its inhabitants. The boats are space shuttles, the foundations become walkways and the buildings a sumptuous scenery. Each step is the general rehearsal for the following performances. Looking closer, it would seem as if we were catapulted into the same universe as Leonora Carrington’s The Milk of Dreams, inhabited by monstrous animals and supernatural beings; here, the lives of the characters change appearance, taking unpredictable diversions, go off the track and become something else. It is the impulse toward metamorphosis and abandonment to its infinite possibilities.

But there are also other forms of life. In the empty spaces left by the sparkling fauna of the openings, discrete and resistant animals infiltrate, who, attached to the walls of the calli, walk straight ahead with elbows high. Their pace is quick, unadorned, and sometimes annoyed. Sometimes they turn right or left, but only to occupy the side paths that they deviate and shorten. And so they become water snakes, eels, moles, and ants: like beings from the underground, they observe the complex movement that happens around them and dig a little space, resilient. Fluid and elastic, they stretch their bodies through the streets with tentacles and tails: for them, metamorphosis is not an alternative, but the only possible way to survive.

For a week, Venice has been island and stage, home, and square: it gives the possibility to be looked at and recognised. Finally, not behind a screen, but in the world—we have to show, conspicuously, that we exist, we have to make it known that we are alive and in a different form from two years ago. We change to manifest ourselves, but also in order not to succumb, aware or not that there is no alternative to transformation.