The 23rd Triennale Milano International Exhibition, titled Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries, opens to the public on July 15 until December 11, 2022. Triennale Milano International Exhibition, which in 2023 will celebrate 100 years since its foundation, is one of the most important events devoted to design and architecture in the international field, and is sponsored by Triennale in collaboration with the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) and Italy’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs and International Aid. The 23rd International Exhibition addresses the theme of the unknown, asking questions about the mysteries of the known world, and opening up a discussion concerning the issue of “what we do not know that we don’t know”. The following is a text by Stefano Boeri for the first volume of the catalogue.

To ask what “we do not know that we don’t know” may seem to be a futile, even ridiculous exercise. And yet if we only stop for a second to take our distance from the repetitive rhythms of everyday life and to reflect on what has happened in the first part of the millennium, we will realise that this question is not rhetorical.

In the space of just a few years, humanity has experienced four great upheavals: the attack on the Twin Towers in 2001, the financial crisis in 2008, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and the war in Ukraine in 2022. Four crises, four global shocks, each of them different in its origins and effects, yet in some way interrelated.

Fundamentalist terrorism, the collapse of financial markets, pandemics, and wars between peoples are, in fact, different and extreme ways through which we might read the now unavoidable and increasingly rapid emergence of a great question regarding the future of the human species, the very meaning of our existence in the world and of our inhabitation of a small planet revolving around a star, a planet that constitutes no more than an irrelevant grain in the infinite system of galaxies.

The emerging question—to which various disciplines, and first of all anthropology as a self-reflective branch of knowledge, seek to give an answer—is whether it is still possible to think of ourselves as a living species capable of inhabiting the world on the basis of a principle of cognitive and cultural distancing from the world itself.

Whether it is still possible to perceive ourselves as a species which is hegemonic because it is able to establish a principle of distance and otherness with respect to the rest of life on the planet. Whether it is possible to continue to exercise the assumption of a “dualism”—between human and non-human, between culture and nature, between human technologies and natural phenomena, between the anthropic environment and natural environments—which has accompanied the development of human knowledge for many centuries.

The answer that Triennale Milano offers, thanks to the 23rd International Exhibition Unknown Unknowns, is that the four global crises of this millennium—accompanied by the continual and increasingly deafening background noise of the climate crisis—can be interpreted as four dramatic invitations to go beyond the founding dualism (or rather dualisms) of centuries of evolution of human knowledge.

We have understood, in fact, that fundamentalist terrorism cannot be treated as something different that can be circumscribed to geographically defined territories and cultures, but is rather a phenomenon generated in the thick of the globalization of human cultures.

Just as we have understood, to our cost, that great financial crises—beginning with the crisis of subprime mortgages—are inextricably linked to our social expectations and ambitions.

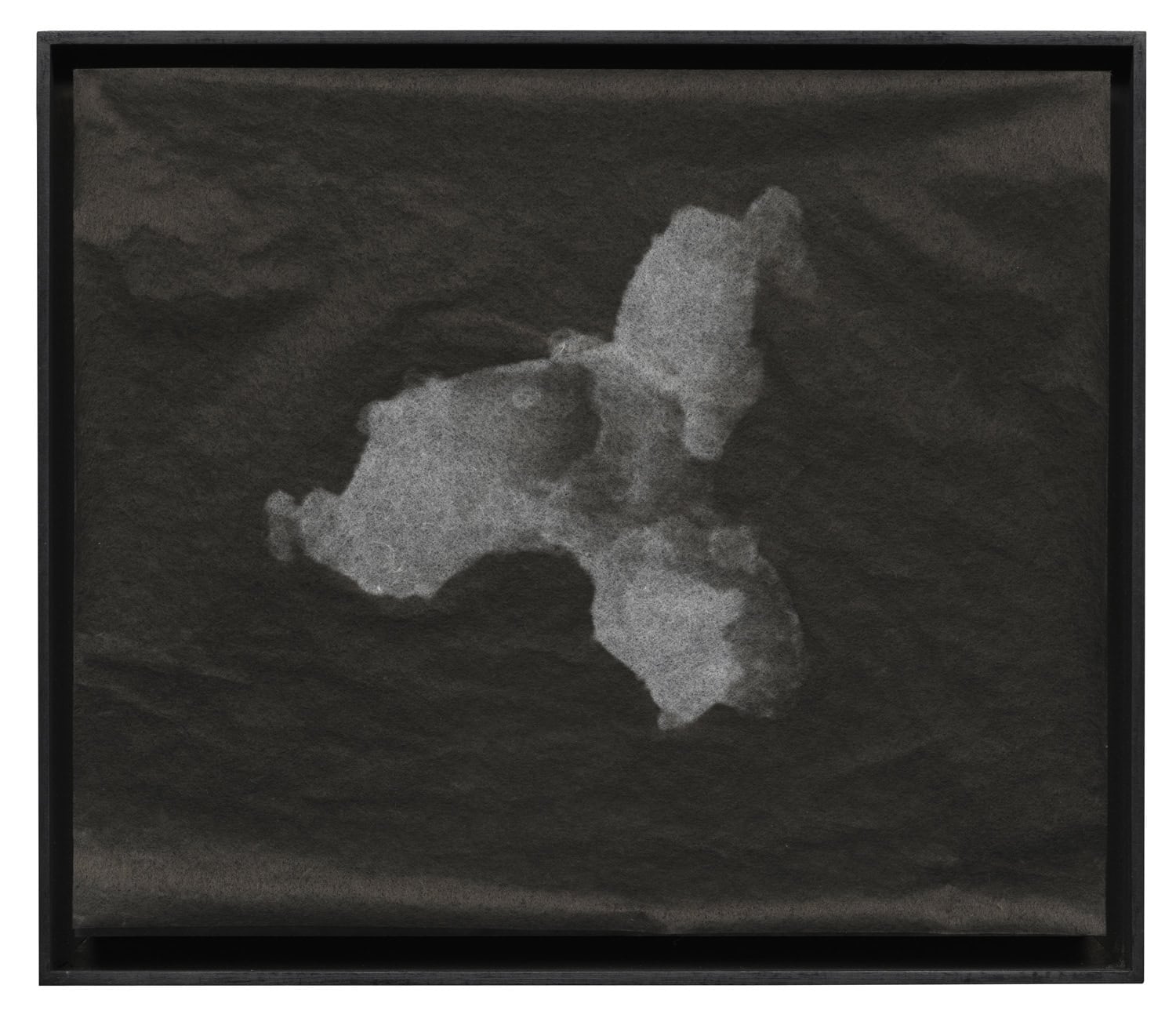

On the other hand, nothing more powerful than the pandemic of COVID-19, a microorganism that multiplies in the bodies of individual members of the human species, could bring us abruptly face to face with the fragility of our clumsy attempts to think of ourselves as “different” from nature and from the (vegetable and animal) manifestations that we have tried so hard to keep outside our bodies, our houses, and our cities, built over the centuries as exclusively mineral environments.

Finally, how can we fail to understand that the flare-up of wars of aggression, of genocides for the conquest or rule of territories, is the crudest manifestation of our belonging in toto to the animal world and to its cruel dynamics of competition for survival.

The truth is that the erosion of dualisms, of the dualism between human and non-human understood as the conceptual premise of our being in the world, has had and is having an immediate role in the extension of the sphere of the unknown, of what we do not know, do not map, and do not control.

A radical development that has the tone and the potency of a new perspective on the world.

For while it is true that for centuries we have measured the evolution of our species on the basis of a criterion of progressive extension, of gradual mapping of areas of the world still unknown, this perspective now seems to have become fragile, uncertain, and insufficient.

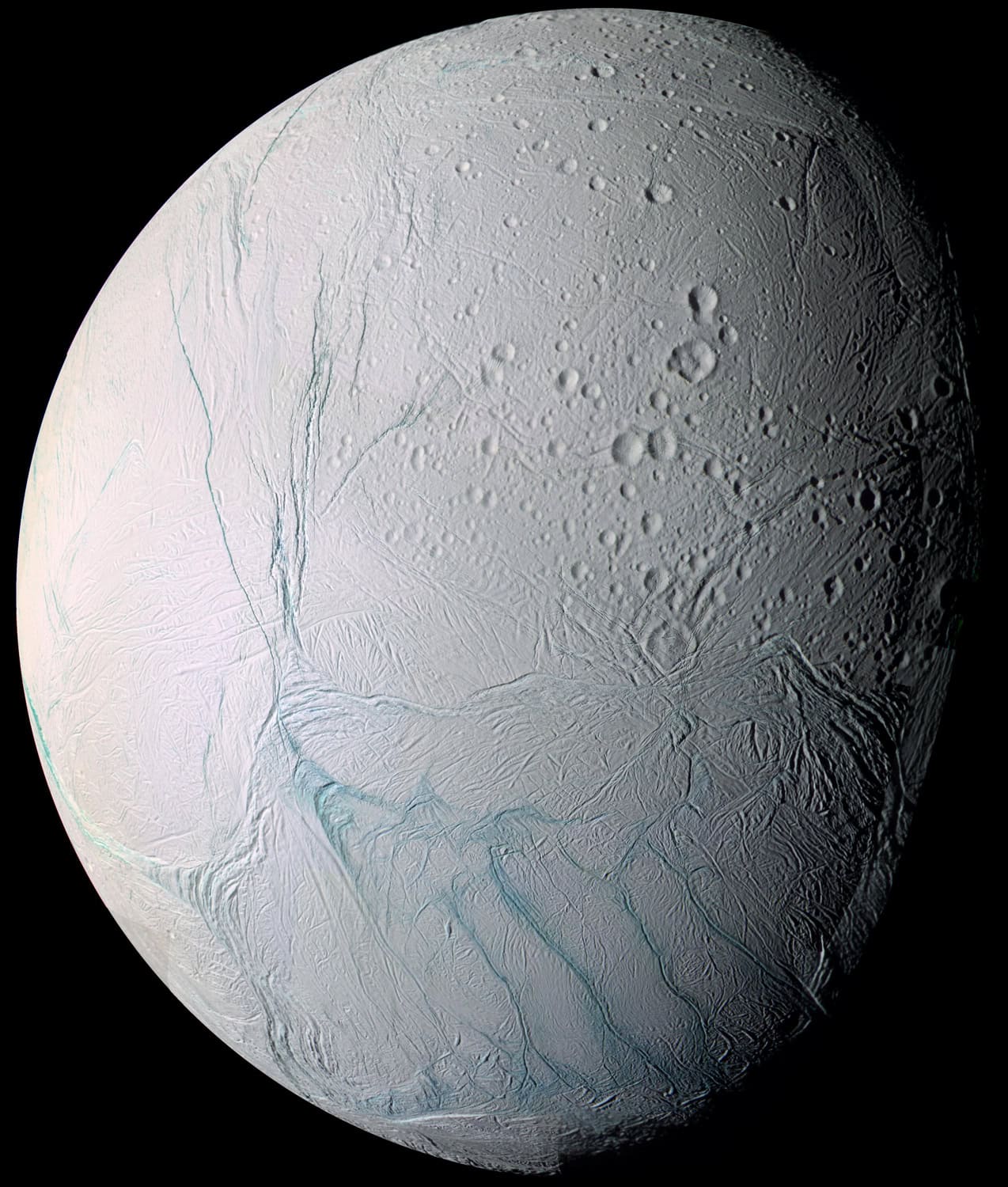

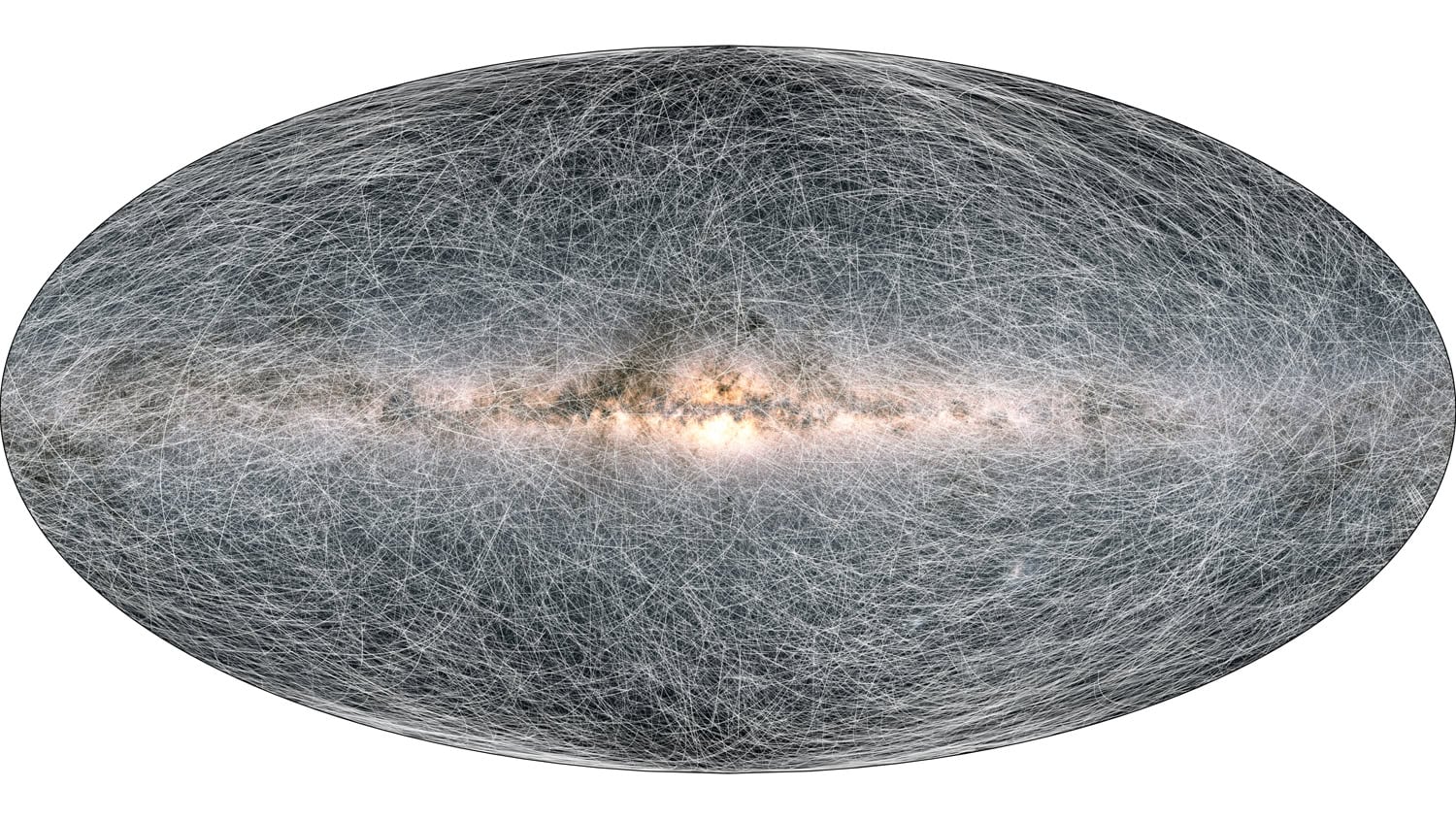

It is certainly true that the natural sciences and the human sciences have accustomed us to measuring—with varying degrees of precision—that which we still do not know: about the universe (95% still not visible), the ocean (95% still not mapped), the lands above sea level (of which we have anthropized barely 5%), even of cerebral synapses.

However, the point is no longer simply to extend this 5% and thus to widen our knowledge in order gradually to fill these vast gnoseological gaps.

The point is that in the age of the end of dualisms, of the mixture between living beings, of the interpenetration of cultures, of the collapse of our ambition to recognise the final limits and horizons of the phenomena of the world we inhabit, we still do not have even a vague idea of what 100% is, of the total and effective field still to be explored.

The forests, the fauna of the ocean, the depths of the galaxies, the neuronal connections, and the changing dynamics of migratory fluxes no longer seem to us to be measurable in their maximum vital and geographical extension. Not only because we have understood that their multidimensional nature cannot be pinned down to a quantitative measurement, that is to a horizon in relation to which we can evaluate the growth of our knowledge “geographically”, but above all because also our life, our aspirations, and the trajectories of our thought inhabit the multidimensional nature of these phenomena.

Within this non-measurable totality, we ourselves are included.

Three years ago, for the International Exhibition entitled Broken Nature, Triennale Milano invited scholars, designers, and artists to return to the natural world the resources extracted, manipulated, and compromised by centuries of human colonisation.

At a distance of only three years, this noble “ethics of compensation” suddenly seems excessively interconnected with the oppositional dualism that has separated our life as the hegemonic species from the other lives and the changing phenomena of the world. A dualism that has made us experience the unknown as a field of conquest and not as a condition to be inhabited and explored no longer with any totalising aspiration.

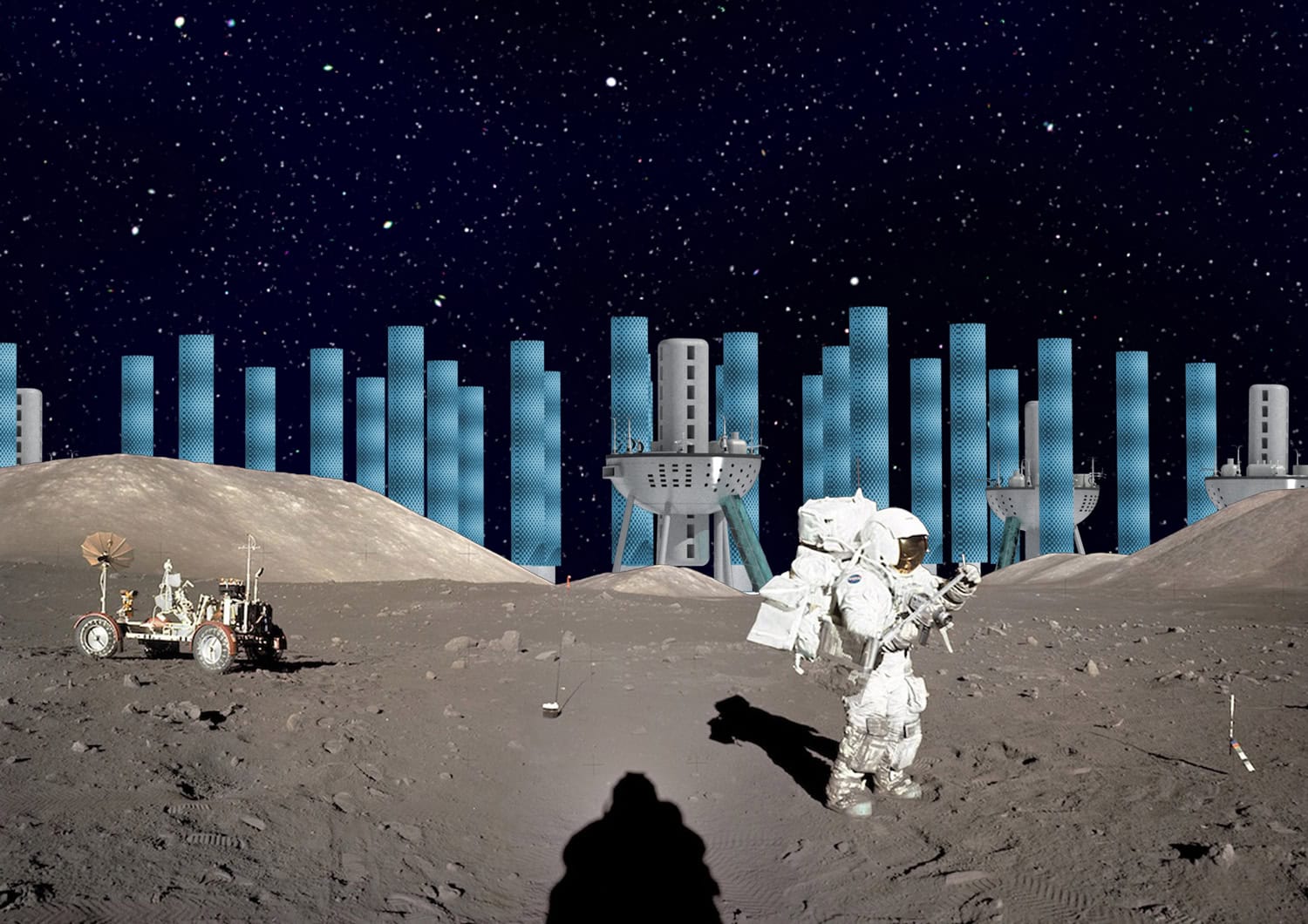

The great constellation of exhibitions, installations, and events which, thanks to the 23rd International Exhibition, will inhabit the spaces of Triennale Milano in the coming months, thus no longer has the ambition gradually to conquer the territory of the unknown, as if it were a battlefield, but rather to explore it with the attitude of the flâneur who, aware of the miscellany of the beings and the entities that flow through the world and therefore through us, chooses first of all the challenge of empathy: the ability—in this case totally and exclusively human—to see with the eyes of other species and of other living beings, and to map the confines of the contemporary unknown from these varied perspectives.

With the irony befitting those who know very well that there is nothing more anthropocentric than aspiring to conquer and represent, entirely arbitrarily, the point of view on the world of those who inhabit it with us.

What we do not know that we do not know is not, therefore, the realisation of a limit, but the perception of a form of knowledge that respects the unknown, sometimes embracing it, sometimes crossing it, sometimes dodging it.

But always accepting it as a constant presence of life.