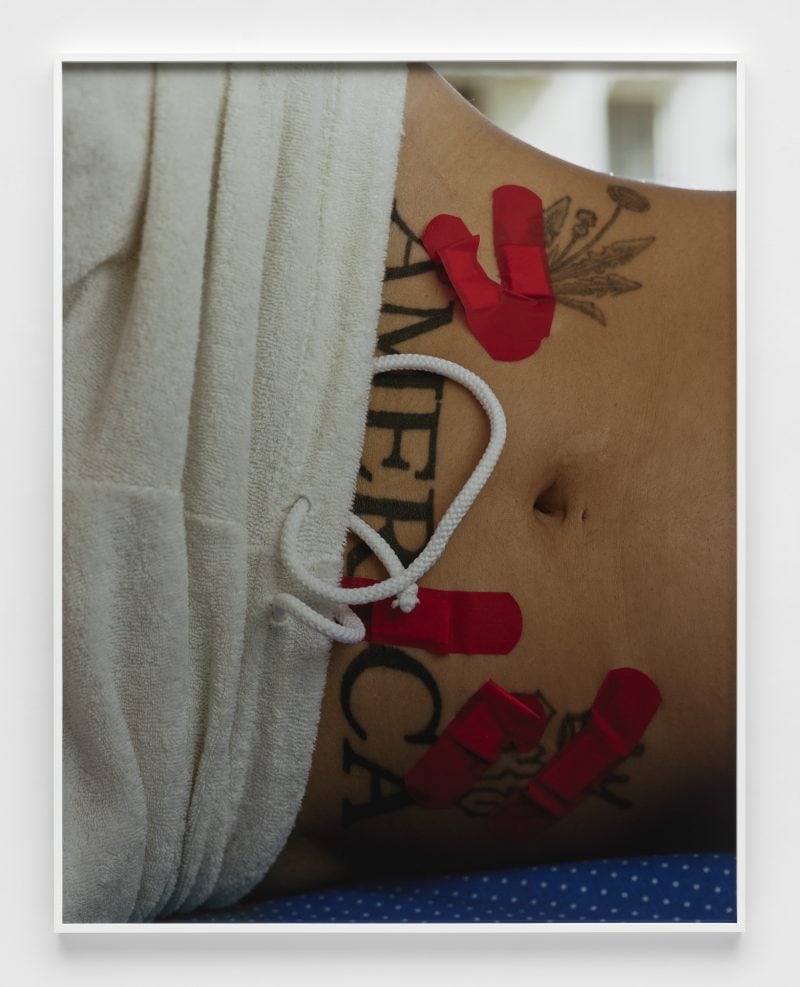

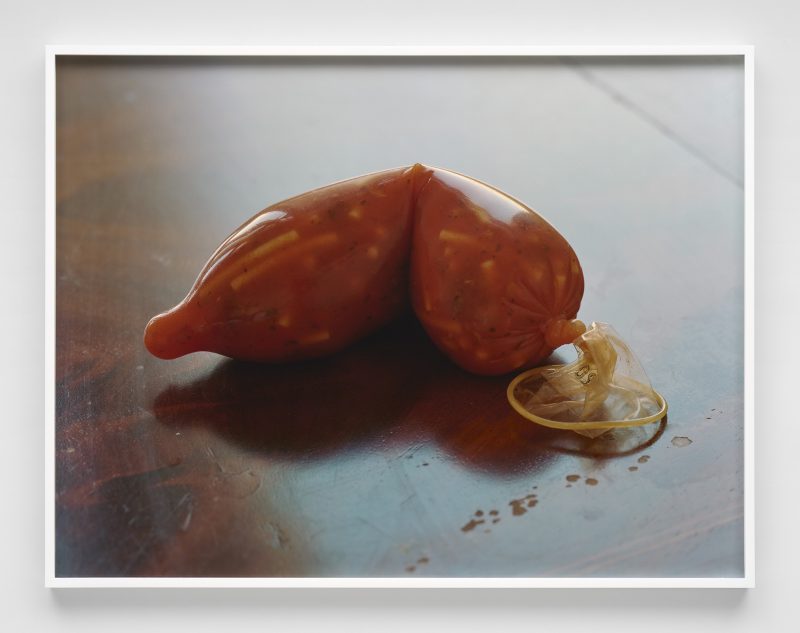

Amid division and endless interpretation, there’s something in Rødland’s photography that, I believe, we all feel at once. His images can never settle. Each frame is a collision site. Opposites grind against one another—ordinary and extraordinary, vulgar and innocent, mundane and divine. Circuits of meaning spark, shift, and mutate long after the image outlives its moment. This is why we keep coming back, always surprised.

In the following conversation, Rødland traces his trajectory along this timeline. He came up in an art world obsessed with everything but interiority—where the author was already dead, and photography teetered on exhaustion. And yet he kept at it. He treats the medium not as a relic, but as fertile, perpetually generative ground, something still capable of yielding value, surprise, friction: viscous liquids ooze across his pictures, but meaning takes root.

Across these pages, a curated selection of Rødland’s work by C41 spans decades of his career, celebrating some of his most iconic images. And as he guides us—or does he lead us astray?—through his visions, his approach, his journeys, we collide with a “dumb universe” that, in his words, is always hungry for meaning, growth, and something just beyond comprehension.

Daria Miricola: Photography hasn’t always been your primary medium. As a teenager, you expressed your ironic and introspective nature through drawings and cartoons. Later, during your university years, you came to see photography as a more fitting medium for your voice. Why did you feel it offered a deeper or more refined way to express yourself?

Torbjørn Rødland: I matured into photography. It’s just closer to who I found myself to be and to how the world presents itself to me. I didn’t approach drawing as a fine art in my teens, it was more centered on cleverness and having a dynamic line. But it was still a deeply creative process to become addicted to. The back-and-forth between what the hand does and what the eyes see drew me into the flow. With analogue photography, this process is drawn out to a ridiculous degree. I now typically wait days before I have any visual results. Still, I prefer it to the immediacy of digital photography.

DM: In much of your work, the light seems to come from behind the subjects, separating them from the background and creating both a sense of emotional distance and an almost sacred aura. What draws you to this particular use of light? What does it allow you to convey?

TR: I stumbled into that early on, while photographing in natural environments. In the beginning I would depict something with sunlight coming from a few alternative directions or angles, but in the end I always preferred the backlit results, and quickly stopped making the others. If I could clearly grasp what it allows me to convey, it may not continue to be so useful, but I think you’re right: the push is upwards, away from the mundane and into the realm of the gods.

DM: Hands and their gestures play a recurring role in your compositions—a detail especially clear in this selection curated by C41. Their presence often feels reminiscent of classical painting. What is the connection you see between hand gestures and references to art history?

TR: I don’t care much for references and language play, but it’s interesting to try to figure out why certain forms and motifs were effective in the first place. It often relates to more or less subtle energies flowing through our bodies. And I do tend to notice hands. I typically want my figures to show hands.

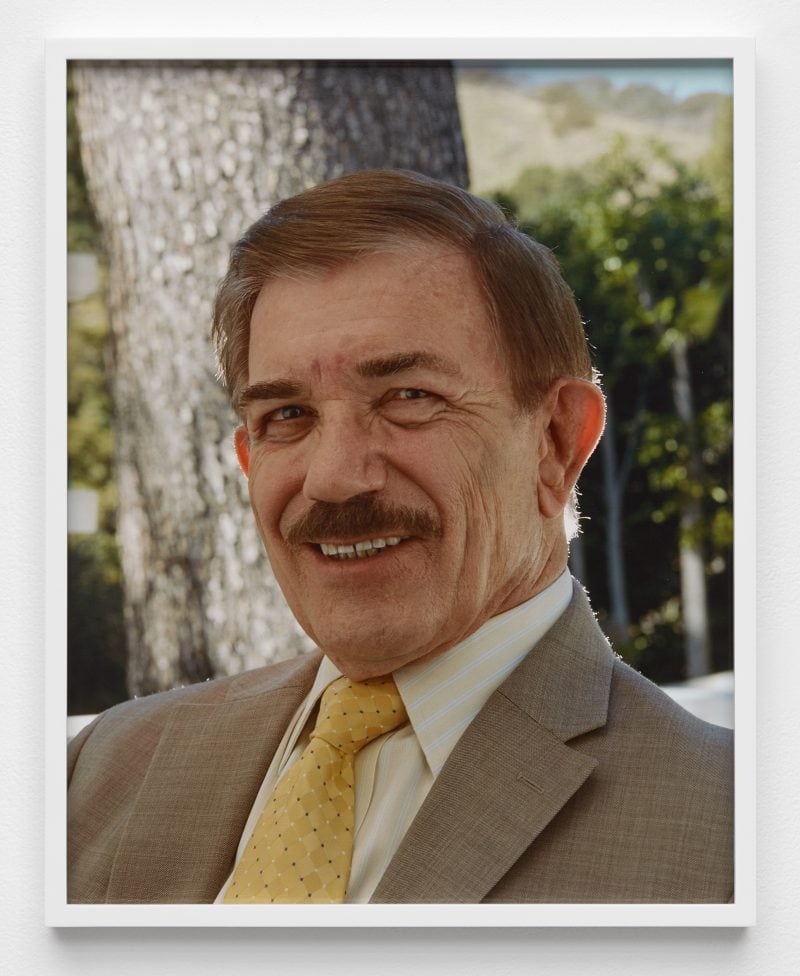

DM: You often work with models who seem to embody a kind of universal or archetypal human presence. Yet when you photograph celebrities, their recognizability introduces a different layer. Do figures like Robert Pattinson or Nicolas Cage still operate for you as symbolic types, or does their fame shift the meaning into something more personal or narrative

TR: Oh, it should always be personal, and the viewer should be able to recognize something in the image, some element that invites them to connect with it directly—without having to go through me, or the idea of me. How the photograph opens up to you changes if you can name the photographed person, and I find that to be fruitful, as long as it isn’t expected or automatic. On the other hand, a portfolio of exclusively celebrity portraits feels limited to me, like letting the medium of photography fall back into a promotional function—something that artists should continue to free it from

DM: Your work encourages close observation and open interpretation. Over time, have you noticed recurring patterns in how viewers respond to your images, particularly within Western culture? What does this reveal, in your view, about how we engage with belief or meaning today?

TR: I just had a group of photographs rejected by the Shanghai police, and their verdict—what can and what cannot be shown—is somewhat mysterious to me. Also in the West, reactions vary and change, even from decade to decade. Since I started exhibiting in the last half of the 1990s, the general direction is towards more trauma-informed interpretation, as I’m sure we’re all aware of. I don’t think anyone sees Jeff Wall’s picture titled Mimic as a racist photograph. It’s allowed to discuss the racist gesture it reenacts. My images are sporadically not granted that type of permission.

DM: Do you also find, when revisiting your own work, that unexpected aspects of yourself emerge? Has photography become a tool for self-discovery or analysis in ways you didn’t anticipate?

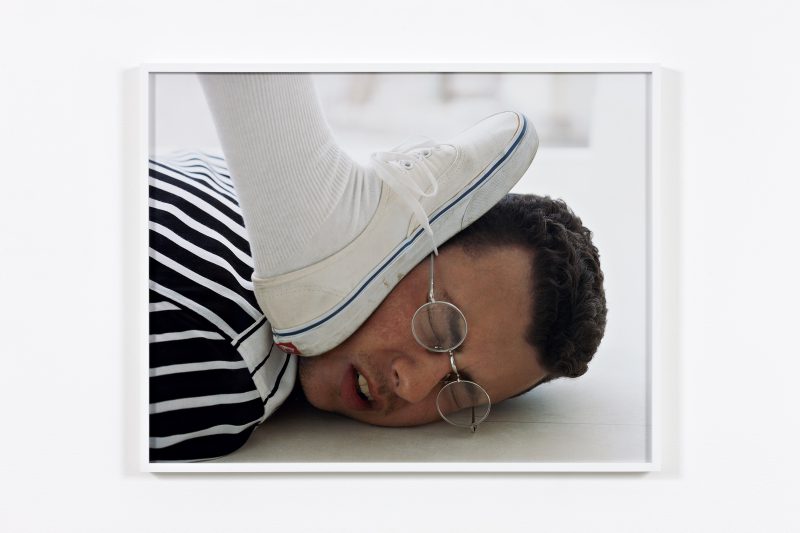

TR: It has, yes. I wasn’t prepared for that function, probably because it was taboo in art school in the early 1990s. The clearest example is perhaps how the sadism I was subjected to in elementary school started showing up in some of my pictures without me consciously deciding to even open up about that.

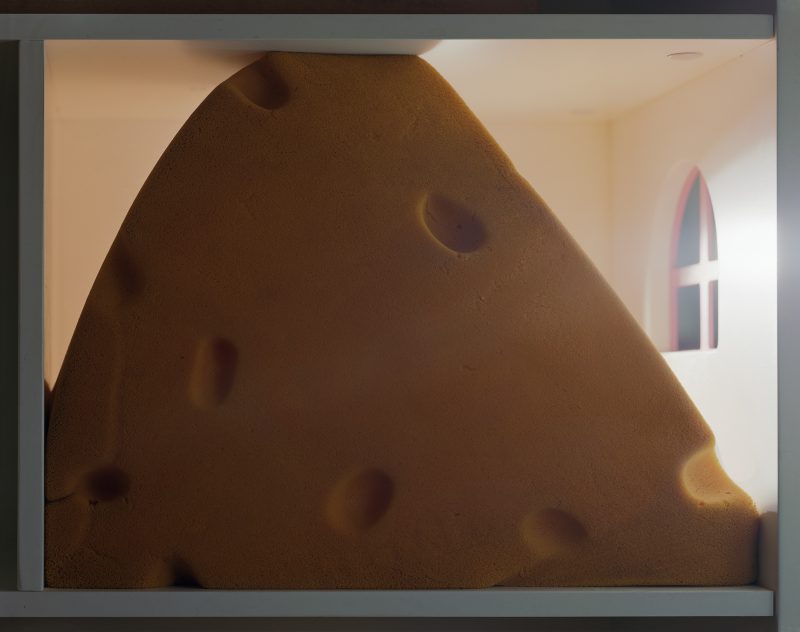

DM: Religion, magic, and mythology have long overlapped, sharing symbolic structures and ways of engaging with the invisible. Your work seems to draw from all three. How do these elements take shape in your practice? And how do you see them functioning in today’s cultural landscape?

TR: In today’s mainstream cultural landscape… I see them slowly break free from jokes and memes, and that is how they’ve emerged in my photography as well. And then I see them find a surprisingly comfortable home in the pictures that our intelligent machines generate. Does that make me put down my camera? No, I’m not delegating picture-making to the computers. But I am kind of impressed by their latest work.

DM: Some of your images evoke a feeling Mark Fisher described in The Weird and the Eerie—a disruption of the familiar that creates a sense of wrongness. Your photographs often feel grounded in reality but also subtly off. What visual choices or strategies do you use to create this atmosphere of estrangement or unease?

TR: Oh, I push and I pull and I stay with it and shake it and throw strobe light and jelly at it until it sings.

DM: Your work has sometimes been linked to the language of memes. Lately, I’ve also been thinking about a connection with the wave of so-called ‘elevated horror” in indie cinema, which often focuses on the paranoid body or Nordic myths and folklore. Films like Swallow, The Substance, Lamb, Men, or Midsommar all seem to draw on these topics. What do you think is fueling this new aesthetic, and do you see your work as part of that conversation?

TR: I do not, because they’re all so narrative, but the argument can definitely be made. It’s about reconnecting with the archaic, I guess. It’s about putting a lot of trust in the logic of the subconscious.

DM: I noticed a recurring motif of polka dot patterns in your work, including in a few images in this cover story. Since your compositions are always so deliberate, could you tell us more about your interest in this particular pattern?

It’s a dumb pattern. I’m drawn to the childishness of it. Yes, didn’t we just discuss the archaic and ways to reintroduce and reconnect with earlier states of development? I like to start with something not normally taken seriously, and then see what happens if I do.

DM: You once mentioned that your photographs—with their minimal, context-free settings—could be taken anywhere. Yet there are psycho-geographical traces of the places you’ve lived in: the mythic quality of Los Angeles, the melancholia and romantic relationship with nature from Norway. Given your deep interest in Japan and the time you’ve spent there, how do you see Japanese visual culture informing your images?

TR: It was mainly the cuteness. I was shocked to see extreme cuteness in mainstream culture. It mirrored aspects of what I was exploring at the time. It was clear to me that Japan had something to teach me. This was at the very beginning of the century, mind you: It was before YouTube and the democratic return of kittens in Western image culture with LOLcats and uploaded cat videos.

Japan also teaches a detailed and nonjudgemental attention to nature. This is perhaps the reason why this island has the best amateur photographers on the planet. Well, at least this used to be the case. I haven’t checked in lately.

DM: Architectural photography has become a distinct genre, though it’s still relatively young compared to landscape or portraiture. In traditional painting, architecture rarely held a central place. Your early work often focused on landscapes, and built environments appear only occasionally. What is your relationship to architecture, and what role does it play when it does show up in your work?

TR: Houses have rich symbolic forms, but I often struggle with all their straight lines. It’s easier for me to work with curved lines and organic structures. Give me a tree house, or a haunted house! The buildings in my pictures tend to be pointing and striving upwards, like castles and churches. Built interior details are common though. In contrast to the exteriors, they typically link or anchor the main forms to everyday realities. I have little use for a seamless backdrop.

DM: Your photograph Baby (2007), which appeared on the cover of Artforum, depicts a newborn whose gaze is strikingly intense. The hand resting on his chest recalls certain religious iconography, such as depictions of the Infant Jesus. How did this image come together? Was the pose directed, or did something spontaneous occur

during the shoot that created this uncanny effect?

TR: Oh, this person was too young to take direction. Do you know the saying ‘preparation meets opportunity’? It’s often like that. I set a scene and compose a frame, and then I’m eager and hungry for what can play out on that scene, within that frame. It’s incredible how much you receive when you’re really ready for it.

DM: I couldn’t find the essay you published in Hyperfoto, titled Telephoto. From what I understand, it explored themes of interiority and exteriority—ideas that still resonate in your work. Could you tell us more about that piece and how those concepts have evolved in your practice?

TR: I think that was the last of the essays I published in Hyperfoto on the heels of my art education. I remember it as an analysis of—or a meditation on—wide versus long lenses: a long lens points to an author to a lesser degree than a wide one. Its world is less subjective. But the idea of an observer in front of the depicted scene returns as binocular-subjectivity if you use an even longer lens. Those texts are in Norwegian, by the way.

I always wanted but rarely managed to prefer a wider lens. In the last year or so, I’ve been more successful than ever before. I find that if you let the medium of photography have its way, it starts digging into those light-reflective exteriors, hungry for interiority. I can say that with less shame now that it’s becoming apparent that computers can demonstrate extensive creativity. The dumb universe is hungry for song, growth and meaning. It never stops.