Takashi Homma (1962) is a Japanese photographer living and working in Tokyo. In a previous life, he gained commercial experience shooting for international magazines in London. However, from the 1990s onwards, his focus shifted to territorial analysis and land investigation, which have defined his style ever since. His explorations started in Japan before expanding to the rest of the world and, in doing so, developing a specific scientific methodology. This new approach led him to question language itself, by reflecting on the very act of seeing and photographing as a way of capturing hidden variations of reality. In 2014, he established the basis for The Narcissistic City, an expansive project published in 2016 by Mack Books, which analyses the most representative and iconic buildings of different cities. The publication opens with an enigmatic sentence from Huber Damisch, exploring the relationship between man and the urban fabric he moves in.

“What kind of gaze does the city license? What kind of gaze does it induce, determine, inform, program, organise? What is the nature of the city as reality, as image and as symbol? What is this object of desire, at once near and ungraspable, fascinating and repulsive, attractive and intractable, necessary and unbearable, intimate and impenetrable, available and inaccessible, that it is for itself as well as for the man of the crowd, for the man in the street, for the man of the city, for those who inhabit it and those merely passing through it, for anyone who knows that it is a labyrinth but nonetheless allows himself to remain trapped in it?” Takashi Homma’s work can be seen as one of these unanswered questions. Even when seeking to explain it, he remains cryptical, almost implying that everyone must follow their own individual and intimate path to discover what lies behind his images. “It is a metaphor: architecture looks at the city narcissistically”, he states. I have to stop and read this again.

My first thought was that he must have an extraordinarily complex relationship with his surroundings but what I couldn’t work out was whether that relationship was predominantly conflictual, or whether in the end it became somehow dialectic. Apparently, this need to examine the city came from the realisation that “existing pictures were inconsistent” and there was still more to unwrap. Before exploring this concept, I needed to understand a key premise. What is it about a city that is narcissistic? I perceived it was something related to the relationship with architecture, but I couldn’t work out whether he considered narcissism a distinguishing mark, or rather an empty assumption, by which all cities are fundamentally equal. It was within this duality that I finally found the essence of Takashi Homma’s ambivalence.

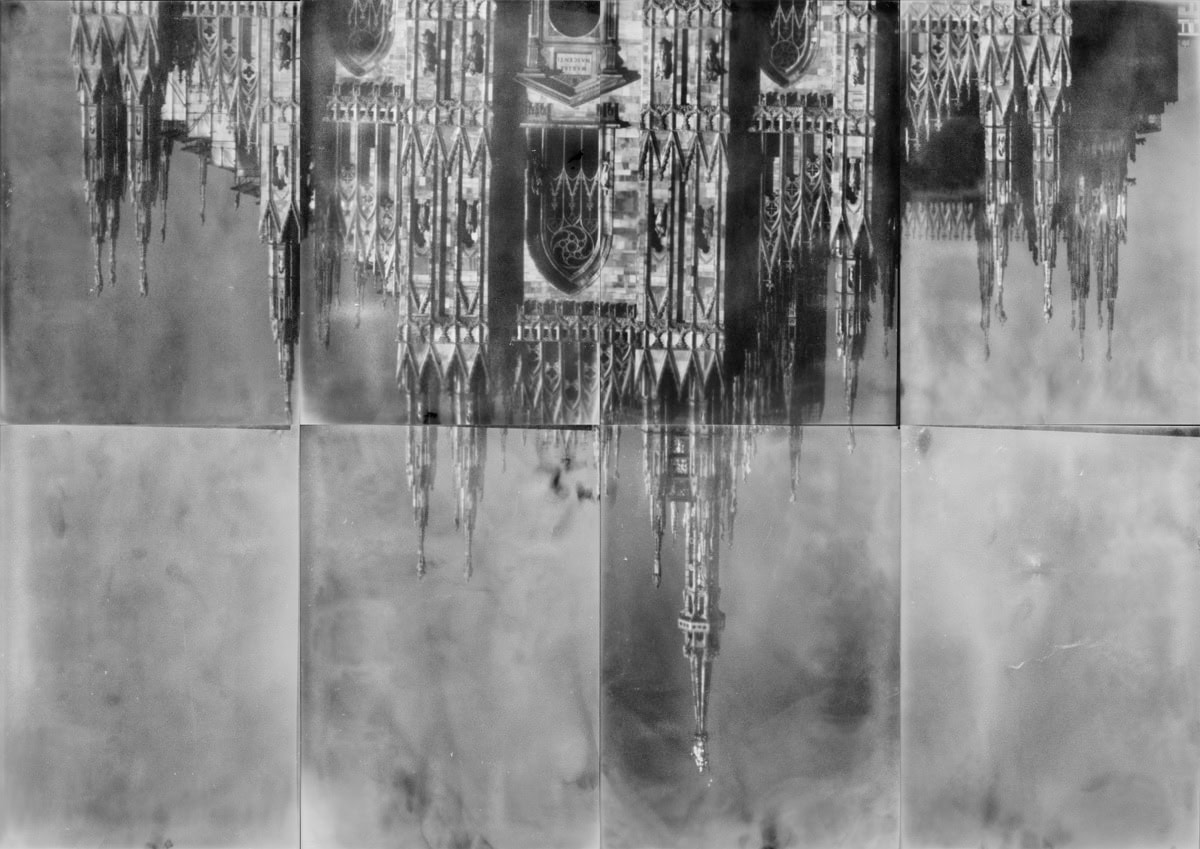

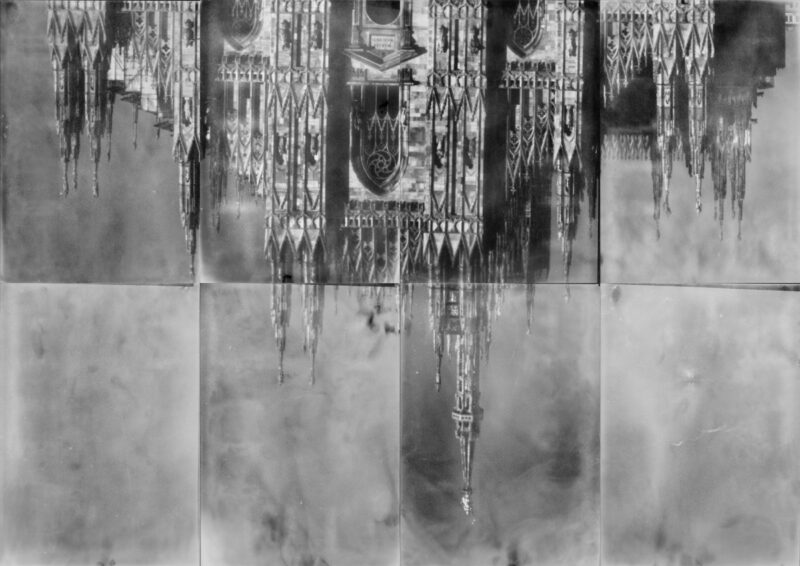

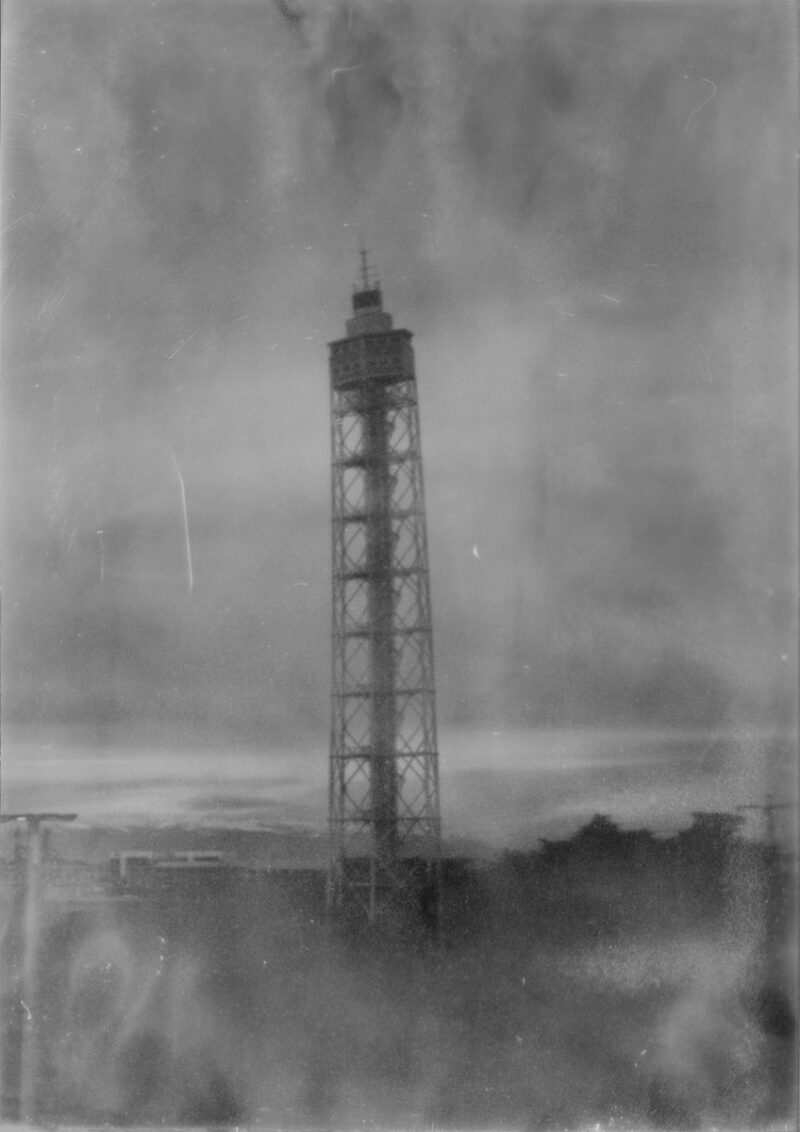

There emerges a common standard behind the buildings the artist chooses to represent. While mostly fitting the description of monumental architecture, he seems to treat each structure quite differently – as though seeking to change their very aura. This can be seen, for example, in the moving (and almost out of focus) images of the Torre Branca, or in the fragmented images of the Milan Cathedral. In this case, going beyond standard architecture photography by combining it with an impressionist gaze shows a specific intent that radically shifts our traditional point of view out of its comfort zone. “I’m more interested in what has been captured, rather than what I shoot”. Once again, Takashi Homma makes us question the very process that precedes the result and asks viewers to critically approach his fragmented images.

We cannot know if this fragmentation is a form of analytical deconstruction or the synthetical reconstruction of reality, but the point is to ask. There is nothing new in this assumption.

Takashi Homma’s work has always been characterised by powerful metalinguistic reflection.

The camera obscura device and upside-down images that define this specific project seem to reinforce this point, by inducing a kind of inversion in how we perceive the places we live in. “I want to shake the viewer’s stable vision”, he states, which is almost stating the obvious given how clearly this transpires from his images. The title reference, on the other hand, has a multitude of layers. In the myth of Narcissus, the protagonist falls in love with himself and eventually dies in his attempts to reach his reflection in the water, turning into a beautiful and ephemeral flower. Similarly, mirrors and windows are recurring metaphors in Homma’s work, a nod to both the cited myth and to architecture itself. They seem to underline the ambiguity of the subjects, as both separating and connecting elements.

The result is a collection of images that elude meaning. Tackling these images head on will not solve this ambiguity. Instead we might do well to remember that this is often the very nature of life: sometimes we see straight through it, sometimes it reflects back on us.

There are no rules.

Credits:

Words by Robin Sara Stauder

Photography by Takashi Homma