Interview with Fosbury Architecture, the “Rhizomatic Brain” that curated the Italian Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale, between the disciplinary crisis and the worlds it can open up.

Rather than get deluded in trying to stitch the cracks of contemporary issues and contexts, this is a curatorial project that looks into their depths in order to find the best point to plunge headlong into them. Spaziale is indeed the manifesto of a generation of Italian architects who, orchestrated by the Fosbury Architecture collective, have given form to a constellation of visions on the architectural panorama that creeps into society with gentle changes, the result of multiple listening and multidirectional observations. Nine stations inside the Tese delle Vergini—the space that occupies the Italian Pavilion inside the Arsenale during the Venice Biennale—tell the story of the project Spaziale. Everyone belongs to everyone else, nine architectural interventions that have unravelled from Trieste to Sicily, signed by as many practices that move easily in the folds of the discipline, supported by advisors and in collaboration with different realities. To tell us about this plurality—in the rigour of a straight, specific and punctual vision—is the collective that curated the Pavilion, Fosbury Architecture, formed by Giacomo Ardesio, Alessandro Bonizzoni, Nicola Campri, Veronica Caprino and Claudia Mainardi, born between 1987 and 1989.

Elisabetta Donati De Conti: When did the Spaziale really start?

Fosbury Architecture: We were nominated at the end of July, and we built the expanded team of curators—even though all the architects, advisors and incubators exhibited today had already been contacted during the tender phase. The process, the rules of the game and the project guidelines have always remained unchanged since our first proposal. However, incubators and interlocutors have increased and have begun to contribute locally to the projects by helping and supporting them. Then the ride began because these kinds of processes, which may seem ephemeral, are actually very complicated on the territory, engaging entire ecosystems and constellations of people.

EDDC: Are these processes complicated to orchestrate, or are they complex because it is hard to get into languages and codes or to understand the context?

FA: All of this because the projects are very different: some had already existed for years and already had their own active network, so it was just a matter for the architects to start collaborating with the advisor and align themselves on the theme that we suggested. For example, Post Disaster have been working on the roofs of Taranto since 2018, and this, produced for the Biennale, is their fourth episode. In this case, therefore, it was a practice with its own consolidated know-how and expertise in how people work in Taranto—which, by the way, is a truly complicated context. They are originally from Taranto, which helps them, the municipality was already involved, and this also helps, and the community already knows what is happening. The one in Belmonte Calabro is also a project that was already active. Other projects, on the other hand, started from scratch. But all of them anchored themselves very well where they acted, and for us, it was essential to avoid the vertical dynamics with which to launch projects of this kind: usually, the antibodies tend to expel a foreign body.

EDDC: How did you avoid this “expulsion” risk in newly created projects?

FA: These were bets based on the sensibilities of the architectural practices. We have been talking, collaborating, living with many of them for years—for decades with some—so we know very well what they can do and what they could have done, and we also called the advisors to boost the projects, but in a precise direction.

EDDC: But even advisors and practices are couples—albeit exploded—that you have somehow imposed. Has this forcing worked by giving rise to unexplored questions, or in some cases, has it castrated some possibilities?

FA: They were softly imposed! The negative case does not exist; some had to leave their comfort zone, especially in the first phase. But when we talk about ourselves as a young generation—even if we are young in Italy when in the rest of the world we are no longer young—and a renewed approach to architecture is presented, it is essential to know how to put ourselves into the game, so we acted as mediators. Apart from perhaps some initial frictions, all the collaborations then got off to a great start. A duo in Trieste is even already thinking about the next project. The inauguration of the Italian Pavilion is, therefore, for us, a moment in which to celebrate a process that will continue.

EDDC: As architects, wasn’t it hard to take a step back from the design point of view? Clearly, your station is not there: you had to design the triggers and somehow then subtly govern these processes.

FA: Obviously all the projects on display are projects that we would have loved to have done, but in our interpretation of curatorship, there is a power of design that tries to find its way into the disciplinary crisis which, especially in Italy, has been permanent for decades now. Unfortunately, we continually witness renewed whining about the architect’s irrelevance.

EDDC: And why is there from your point of view?

FA: Because we live in a context that has completely changed: today, the archistars are waning. We believe that this Biennale can mark the sunset point of that approach, that of the architecture of the beautiful gesture, of the demiurge, of architecture as a solution and not as part of the problem. This Biennale, on the other hand, questions the role of the architect since construction is the second most polluting sector in the world. We are part of extremely extractive processes.

EDDC: The disciplinary crisis is, therefore due to the fact that the figure of the architect can be assimilated to that of a builder and not to an orchestra conductor or planner of services, experiences, travel arrangements, ways of being together, or other dynamics that resulted from the projects on display here. What can we start to trigger this cultural paradigm shift? Other countries have done it.

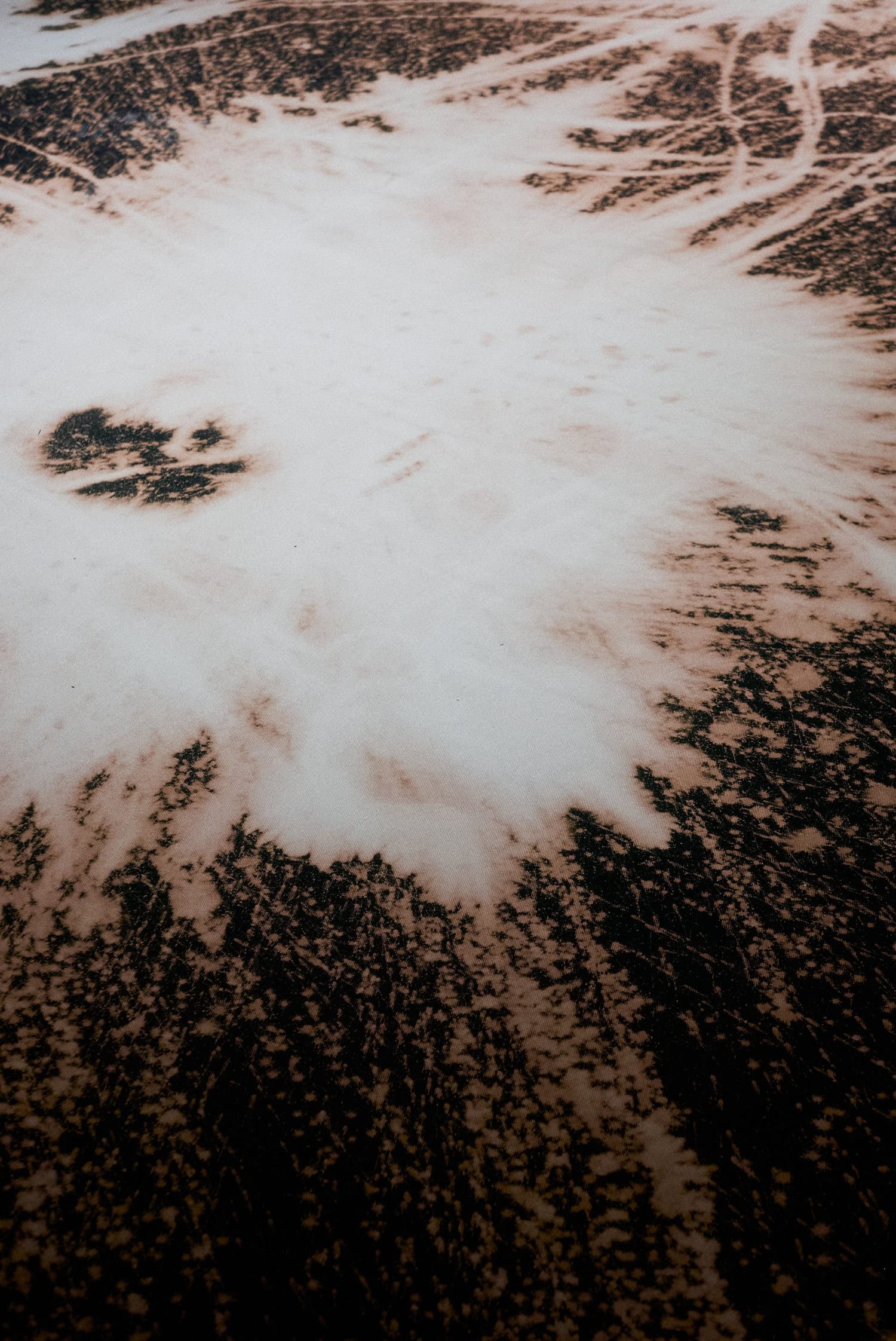

FA: Other countries have even historicized it. Obviously, even in these places, it is a niche, because architecture and construction are undeniably connected—where, in other words, economies move. However, these addressed in Spaziale are examples of urban regeneration that look at other ways of regenerating cities, without the twenty-year masterplans, without the great urban visions, which then fail to take into account an evolution of the world that is too rapid. The paradigmatic example here is the project by Studio Ossidiana, Librino, the name of a utopian neighbourhood designed in Catania by Kenzo Tange, which has remained unfinished because it is the result of the idea of doing total projects on a linear and positivist vision of human evolution, a line straight which is absolutely not the context in which we live today. Today, however, hosting this kind of architecture at the Biennale is already a victory for us. There is a world that opens up around these practices that we believe can grow, also to get the disciplinary crisis out of introspection, broaden the horizon of architecture to hitherto little-explored fields, but also affirm that we architects can have a role, an agency in the transformations, which must necessarily take into account the climate crisis that is now here. We can play a key role precisely because every crisis has a spatial dimension: we are ready to dominate it, but we cannot always detach from this easy marriage between architecture and the built as the ultimate and only goal.

EDDC: Where are these practices normally? Obviously, if they get here, you have brought them to the surface, but their seed often already existed. Like Concrete Jungle by Parasite 2.0, it is a project from scratch but which is grafted onto a very defined pre-existing situation, or Lemonot’s project on the mullet roe supply chain in Sardinia. Why, then, since these practices already exist, are they not culturally recognized as architectural practices?

FA: Often due to disciplinary myopia, which tends to exclude or label a certain type of operation as artistic. We do our part by calling ourselves “practices”, even removing the role of the designer from the definition. But no one really winks at art–they are all architects, and so are we, all trained in architecture and capable of doing that fundamentally. In a transdisciplinary way, but that. Italian architecture is too often entrenched in the few concrete opportunities we have to build, neglecting the possibility of expanding the field and evolving.

EDDC: The task and purpose of architecture is, moreover, to ground an idea in the most transformative way possible.

FA: As architects, we realize that it is destabilizing when you don’t have a physical artefact at the end of a process, but many times, even if there is nothing, something has happened. This destabilizes precisely because a somewhat conservative class forms us with respect to a disciplinary vision that taught us this straight process: from a to b.

EDDC: How did the genesis, the idea or the spirit with which you wanted to carry on this curatorial project, which is very political in reality, develop?

FA: We try to avoid the political dimension because we find it rather fruitless. It is a disciplinary matter, which only sounds political because it has a political impact.

EDDC: But you bring forward some instances, and this is political.

FA: Exactly. However, there is the risk that being on the political level, discourse could be exploited. On the other hand, on a disciplinary, procedural level, it is possible to protect the path, which is where we want to take root, also to protect the practices on display. Obviously, then there is a political dimension that clearly emerges, above all, from certain planning intensities that are exhibited here.

EDDC: Doesn’t shun the political dimension slow down the process of scarce cultural recognition of a phenomenon?

FA: It is precisely this collective dimension of ours that helps us to mediate in this respect as well. What comes out of the group is already examined by the group: it seems chaotic to work in five, but by now, we are almost a Rhizomatic Brain. Fosbury has always been a platform for individuals working independently on other projects, full-time, part-time, working at night or when we could, on projects we strongly believed in, activating Fosbury only at specific times on specific projects. In turn, the activities brought to the Pavilion are not part of a laboratory of the future but of the present. They live so rooted in the reality that they are constant compromises. We are a generation capable of compromise. While architecture, up to a certain point, has only expressed self-assurance: even the radicals were extremely convinced of what they said. We, on the other hand, have a lot of doubts. Us and everyone else. So mediation is perhaps the most powerful political weapon we have developed and shared with all the invited practices.

EDDC: Perhaps doubt is also what characterizes a Rhizomatic Brain, in antithesis to the cultivation of the ego.

FA: The collective at the beginning serves to dilute fears. We had many doubts and few answers, an uncertain background due to our training and the fear of entering a post-2008 economic crisis market. So we huddled together and threw ourselves on the other side into the real world.

EDDC: This Biennale gives the feeling of wanting to normalize the architectural acts to be brought to events of this kind. Biennials are, by their nature, moments in which to present ultra-special things, the pinnacle of research or very successful, super-virtuous things. On the other hand, the normalization of the architectural act opens up possibilities for everyday life in which architecture usually does not enter without necessarily having to tie it up with ribbons.

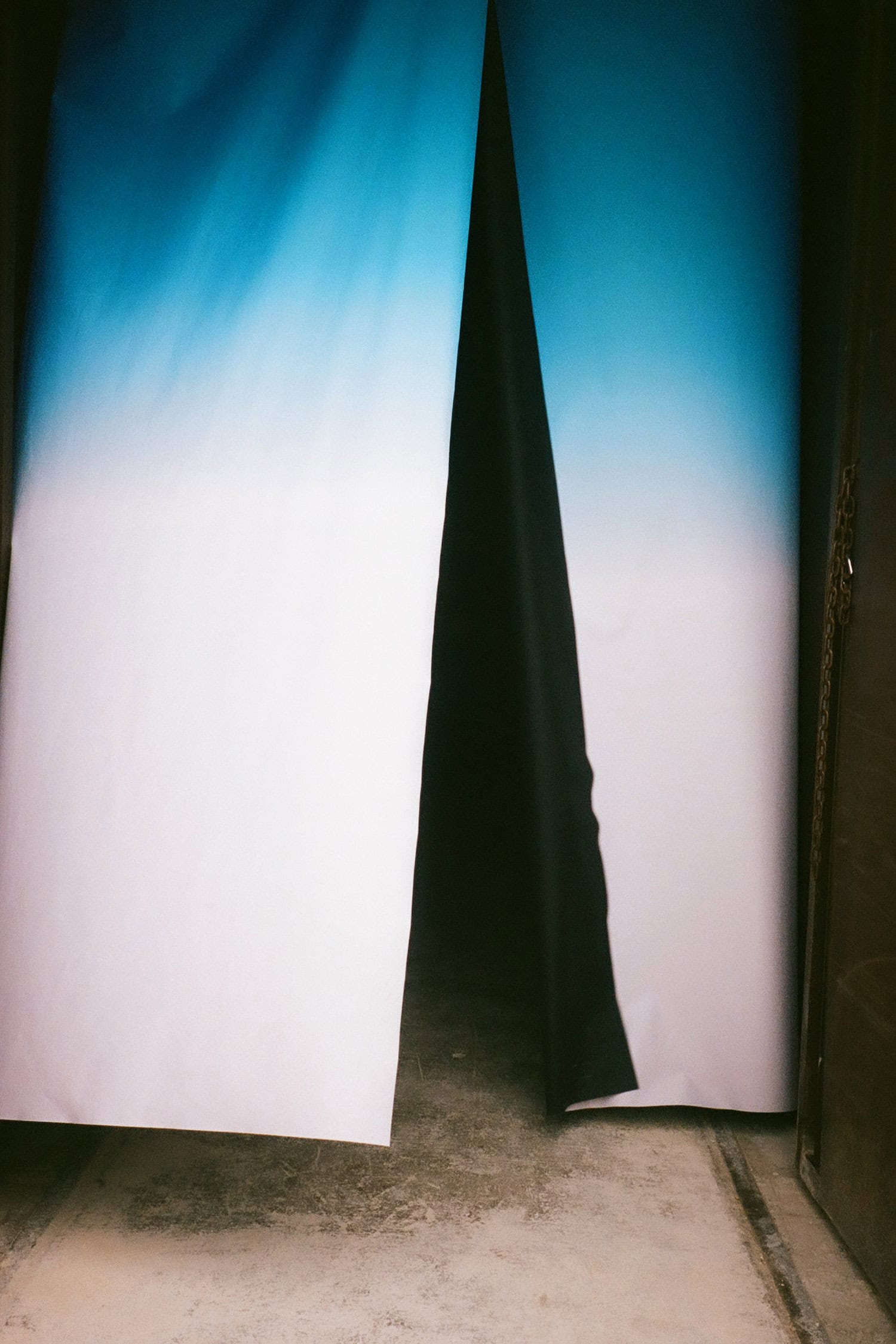

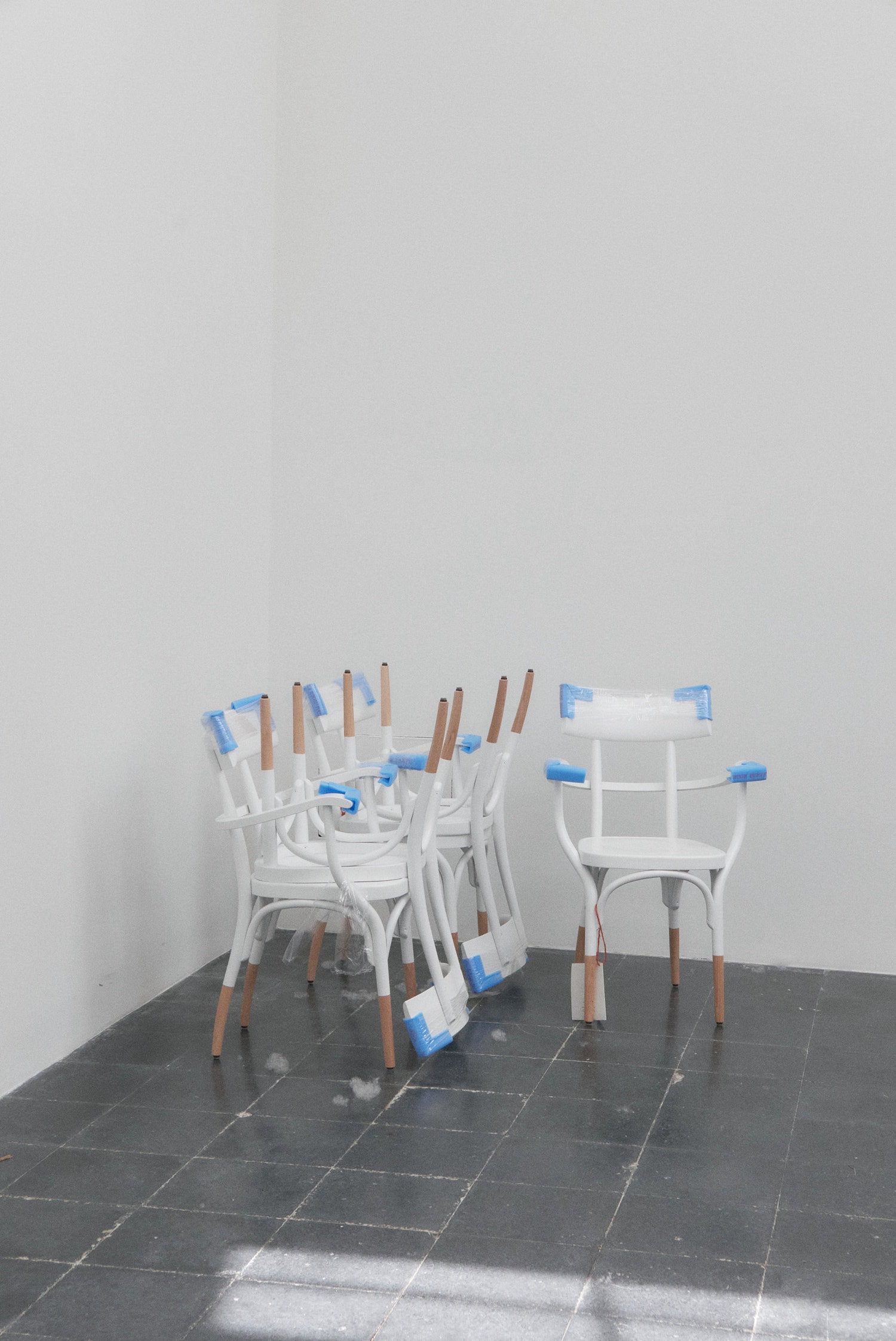

FA: For us, it was important to invest a good part of the budget in the territories, and here in Venice, we brought the essential minimum to document and celebrate a moment of synthesis and celebrate moments like the Biennale, but without impoverishing the processes that are elsewhere and that deserve all the resources possible. In the Arsenale, we have brought just enough to place people and works into the abyss, the space-time from which they come (and where they will return at the end of the Biennale), but with a process of reduction, evident above all in the first area—where the void is the protagonist, and consequently space is.