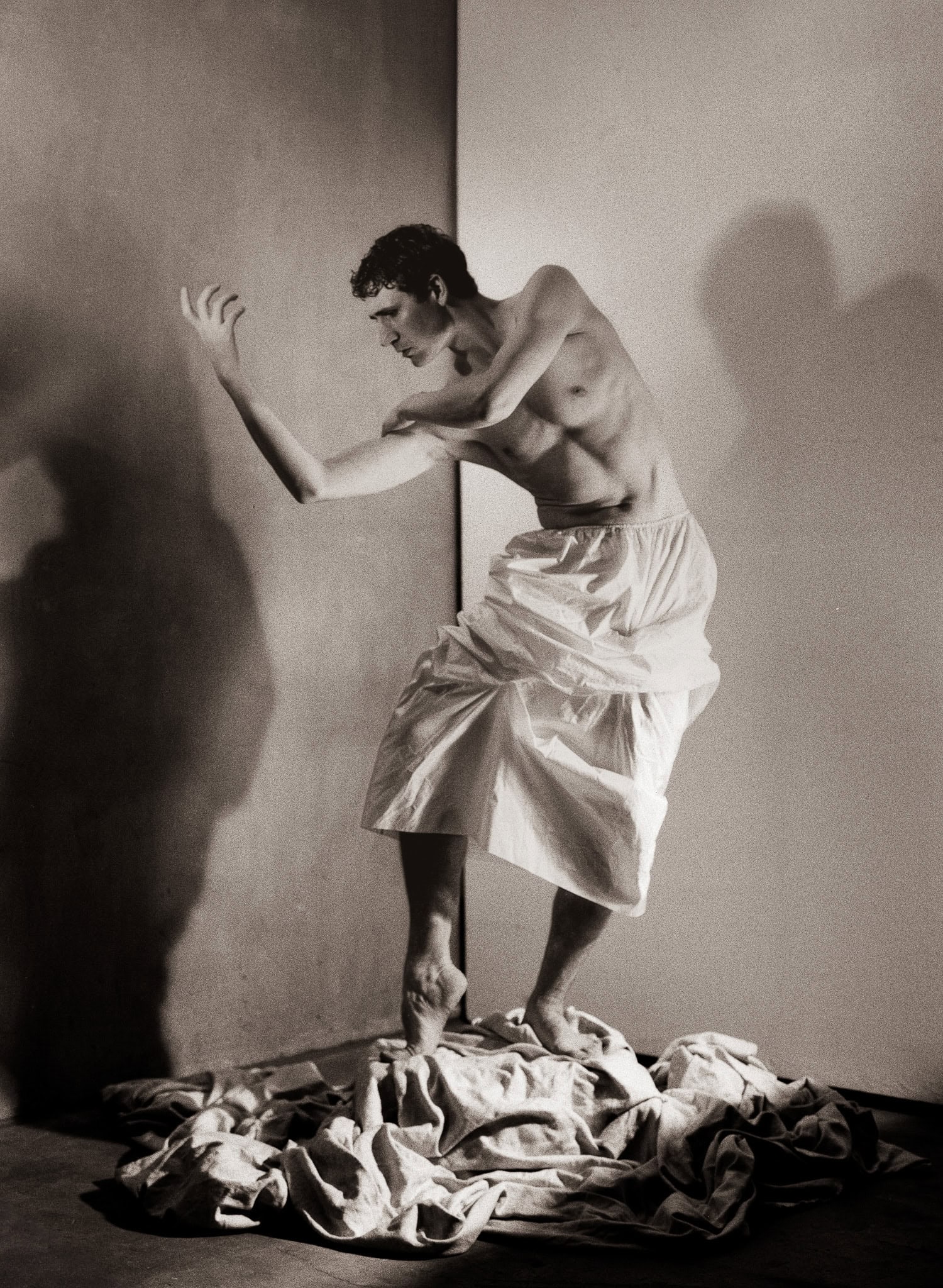

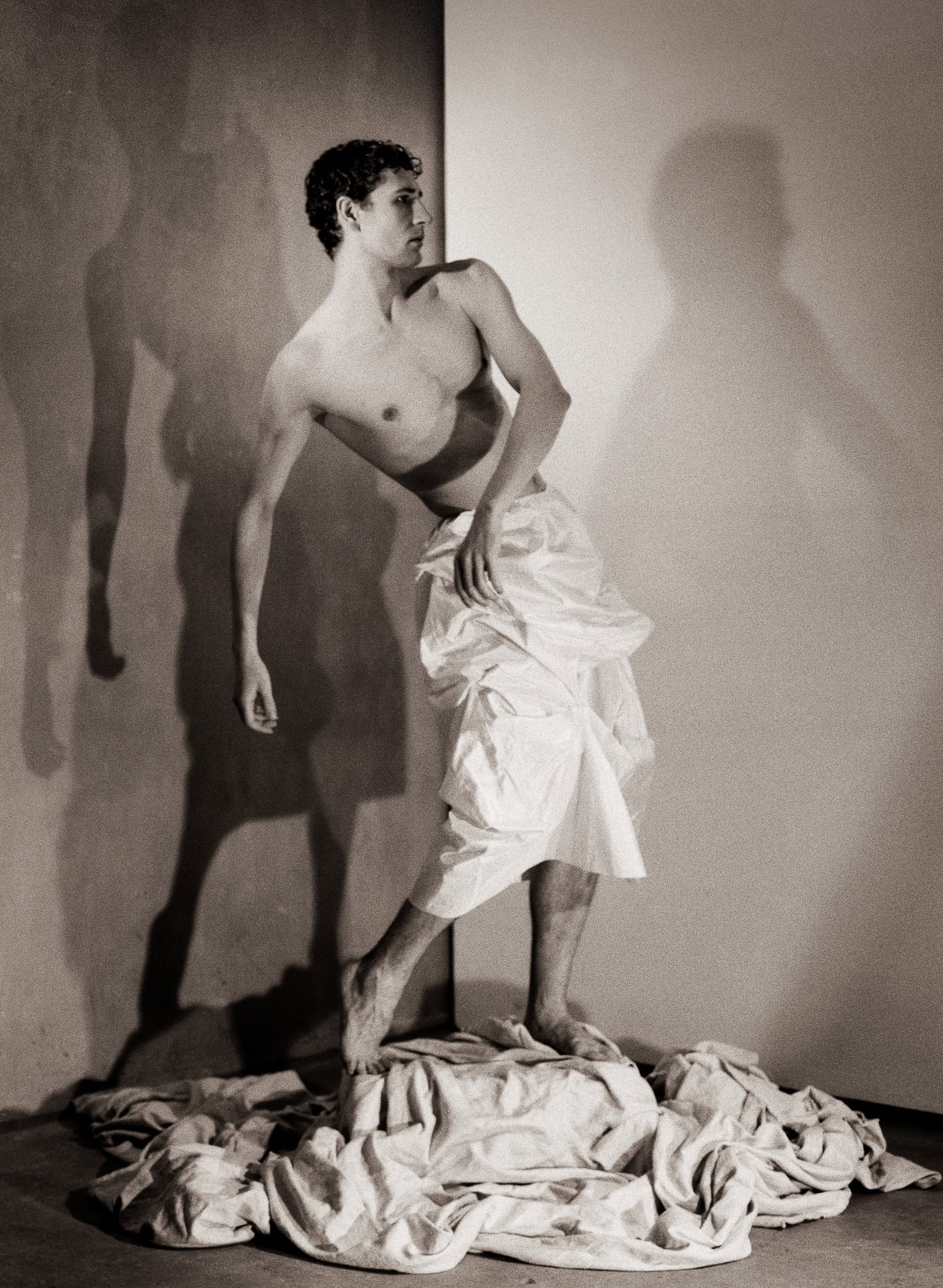

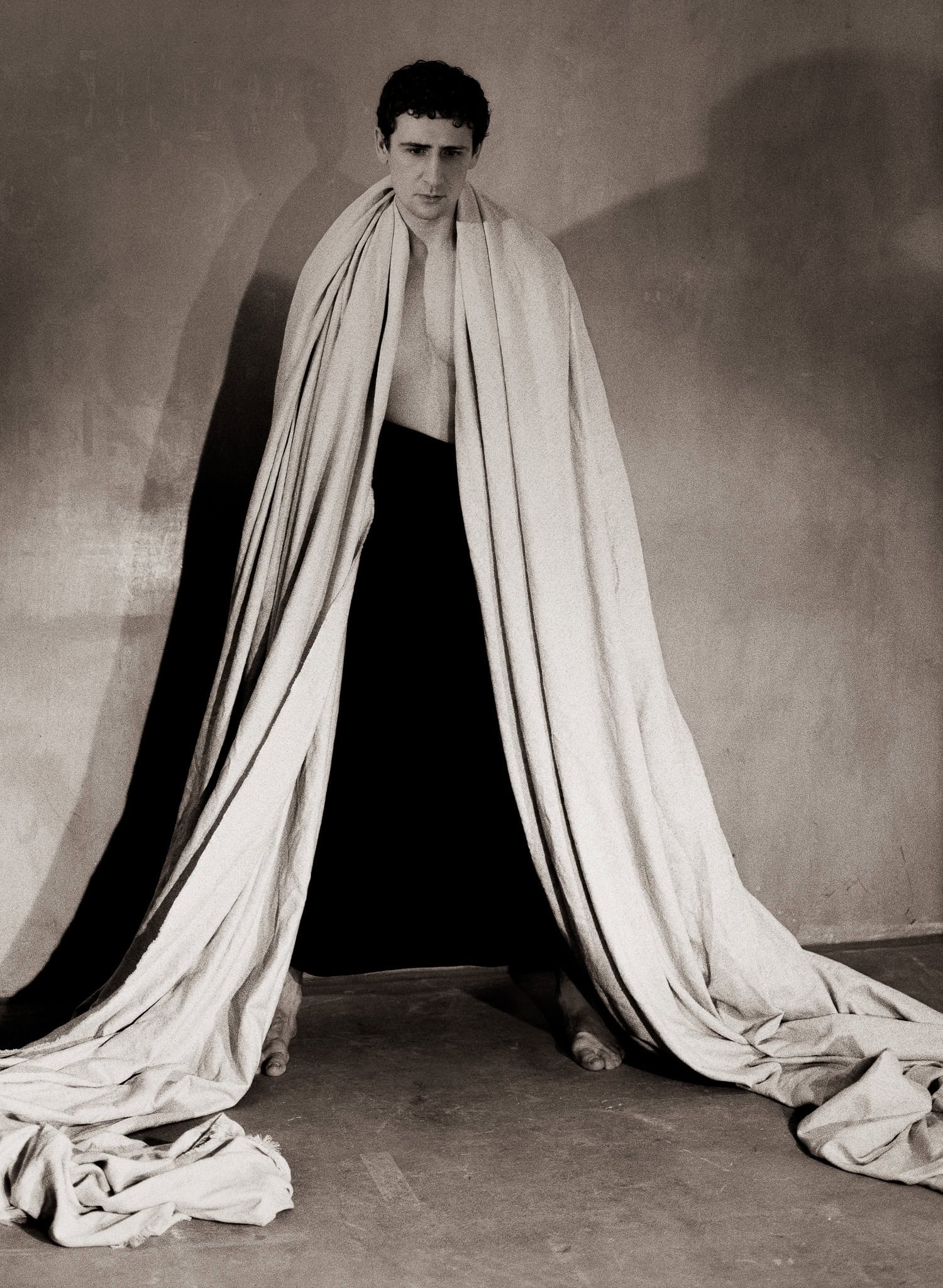

I recently had the pleasure of collaborating with Pascal Johnson, a former dancer with the Dutch National Ballet, now a movement director and producer who has worked for brands like Apple, Calvin Klein, and Nike, on a photo series that grew into something deeper. What started as a visual exploration turned into a dialogue about presence, memory, and what exactly an image can and cannot truly hold. Together, we approached the process as an open-ended reflection, using movement and stillness through the visual medium of photography to investigate how the body carries memory and inhabits the present.

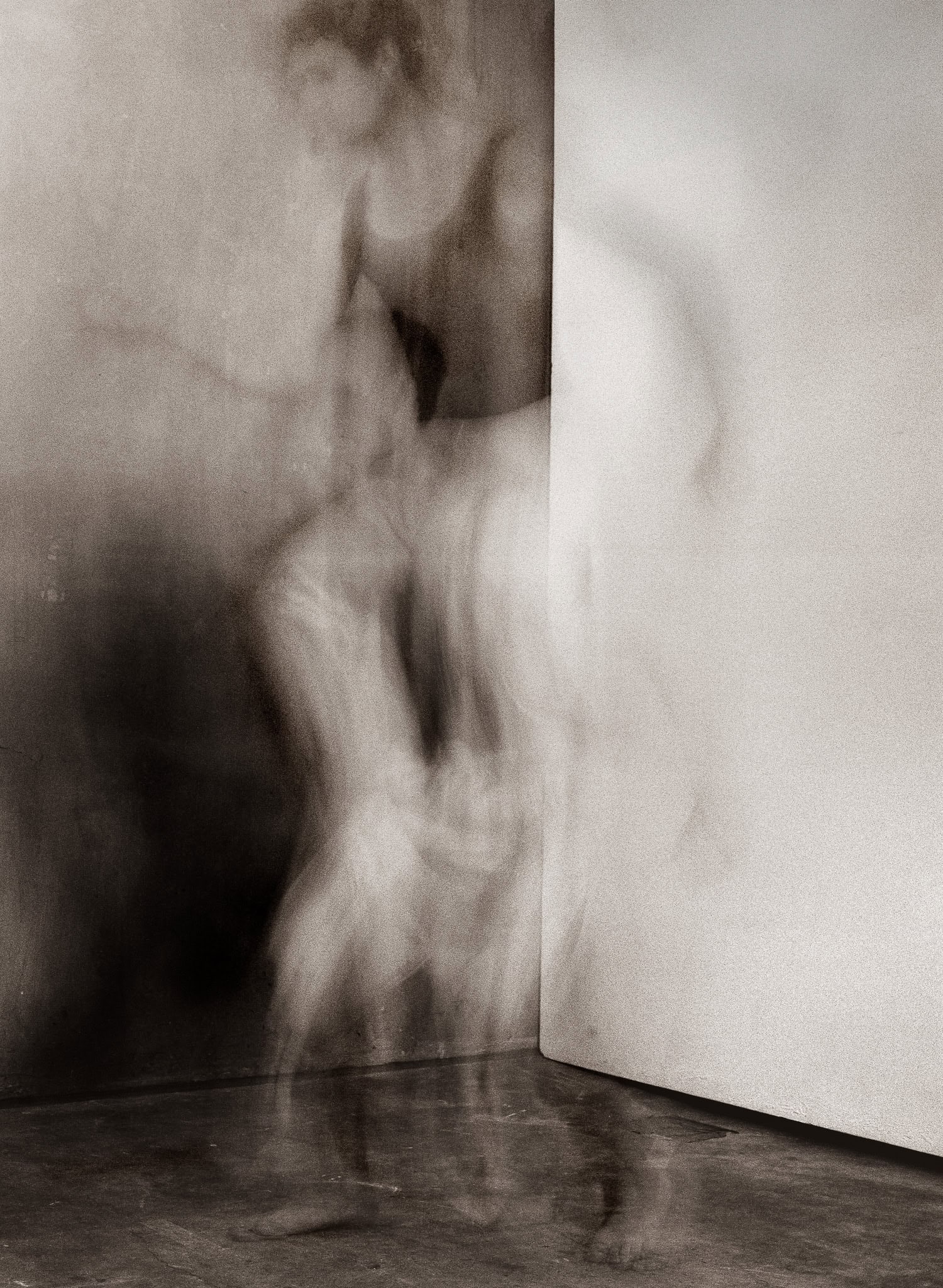

At the heart of this series is a complicated question: can we ever really preserve something fleeting? We often believe that by permanently affixing a body into image that we are holding on to something true. But permanence does not equal meaning. Time strips away context, and leaves behind a thin surface, a static impression of a figure that once moved with thought, fear, laughter, and love. What is left is a fossil of ego, a trace of something that was never meant to be still.

To dig deeper, I sat with Pascal to speak more on the process and the themes that surfaced: presence, vulnerability, the space between movement and memory, how his experience informs his practice, and what it means to embody the present and whether it can ever truly be captured in image.

Aaron Alan Mitchell: How has your experience of being a Ballet Dancer informed your approach in movement direction?

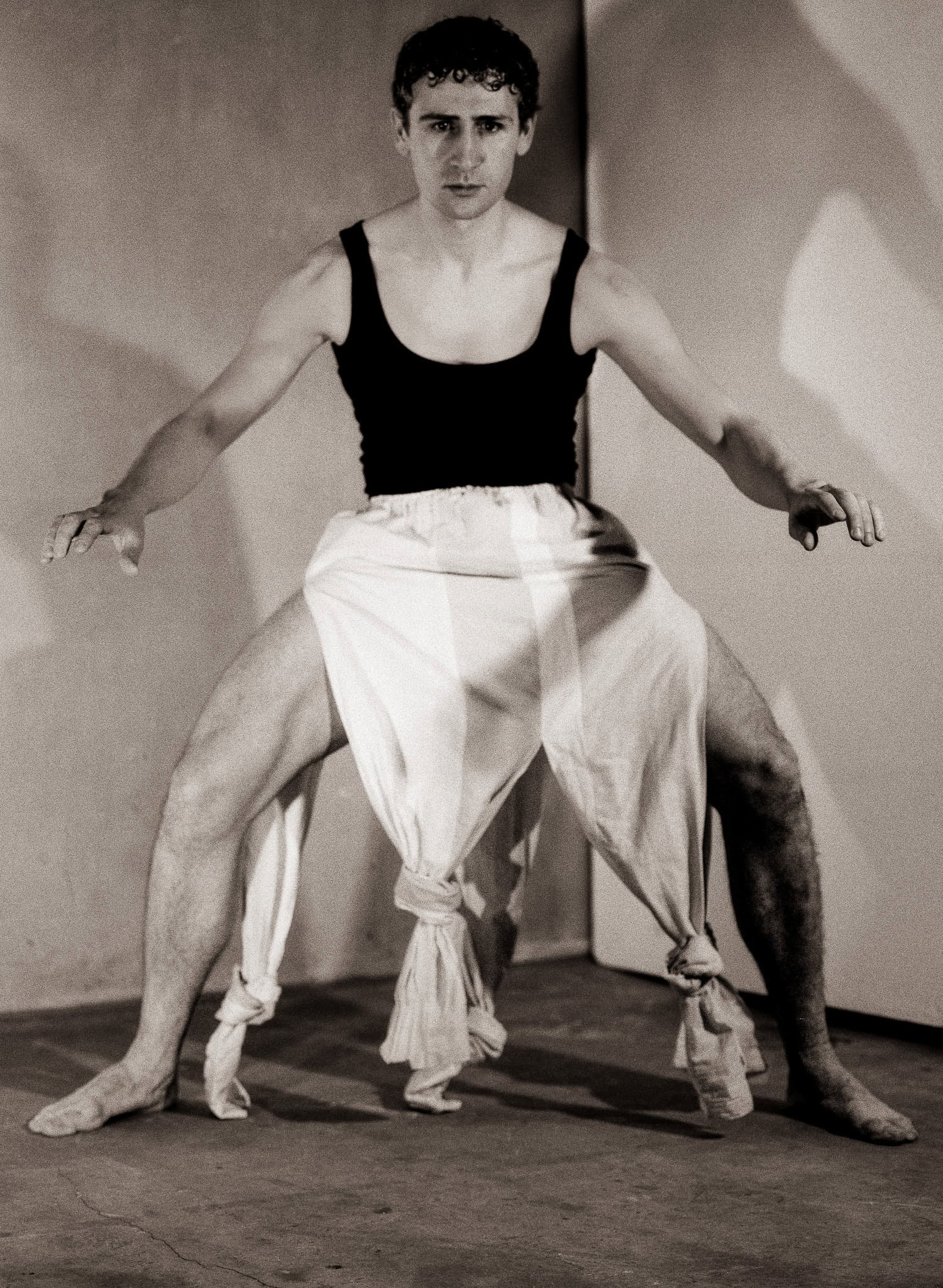

Pascal Johnson: Having been a professional Ballet dancer for ten years, the balletic aesthetic informs the way I see everything: physicality, posture, dynamic. This perspective brings a lot of clarity in movement and precision. Now, being at the front of the room, I always strive for collaboration and openness, which was not always a given in the world of Ballet.

AM: How has the transition been between performing and movement directing?

PJ: This project was an interesting step back into performance and into remembrance of the physical body. Collaborating with you, Aaron, was a nice invitation to explore my own physicality in the present. Having retired from performance two years ago, It was quite vulnerable to open myself up to such a clear examination through the visual medium of photography.

AM: Do you see the body as a more honest archive than the image?

PJ: I would personally say no because movement is impermanent. An image can capture a movement or a moment but it’s as fleeting as the crest of a wave. Though, of course, the body remembers but yet it cannot perform forever.

AM: What role does vulnerability play in your choreography?

PJ: Vulnerability and honesty go hand in hand for me. Without an honest performance or intention I think the work lacks sparkle or interest. So, I would say vulnerability lies more in the hands of the performer than in mine as choreographer or movement director. Any movement done with honest intention can be interesting. Even the most beautiful choreography can be dull without vulnerability.

AM: Can movement capture essence more truthfully than memory or image?

PJ: I think so, in quality. Though movement does have limitations in adding context or history, because it is always fleeting and unique. On new projects, I often ask myself why this concept should be told through movement, what can it add?

AM: How do you explore the tension between permanence and impermanence through movement direction?

Pj: Enabling a space for a performer to both channel direction and explore the impermanence of movement is very important. For me, this hinges on memory either in muscle or feeling. The tension becomes real through the practice and rehearsal needed to create such impermanence in movement. What is interesting is that the feeling itself is remembered but the movement is gone.

AM: What is ‘the present’ to you when you are performing?

PJ: The best performers are present but it’s a challenge to achieve. It requires one to be honest with themselves, their bodies and the audience. In image, this is even more important as the camera witnesses every detail as we seek to capture the ephemeral present.