Have you ever wondered what it would be like to craft jewelry using the materials you find around you as you journey through different realms of

nature with your van?

What started as a casual fascination with metals and minerals during a van trip across Europe in 2021, Anniken Øvrebø has delved into a deeply rooted created practice starting from Mother Earth and ending on our bodies. A process that is sparked by creativity and guided with intuition and respect for her surroundings, Anniken creates beautiful hand crafted adornments rejecting the ideology of man vs nature but unifying the two with respect and admiration for the two.

In this conversation, we explore the journey from earth to body—how tinkering and collecting became an artistic language, why imperfection is a kind of beauty, and what it means to wear a fragment of the world.

Nisha Kapitzki: What first sparked your interest in jewelry making? And how did that process carry into your travels in your van?

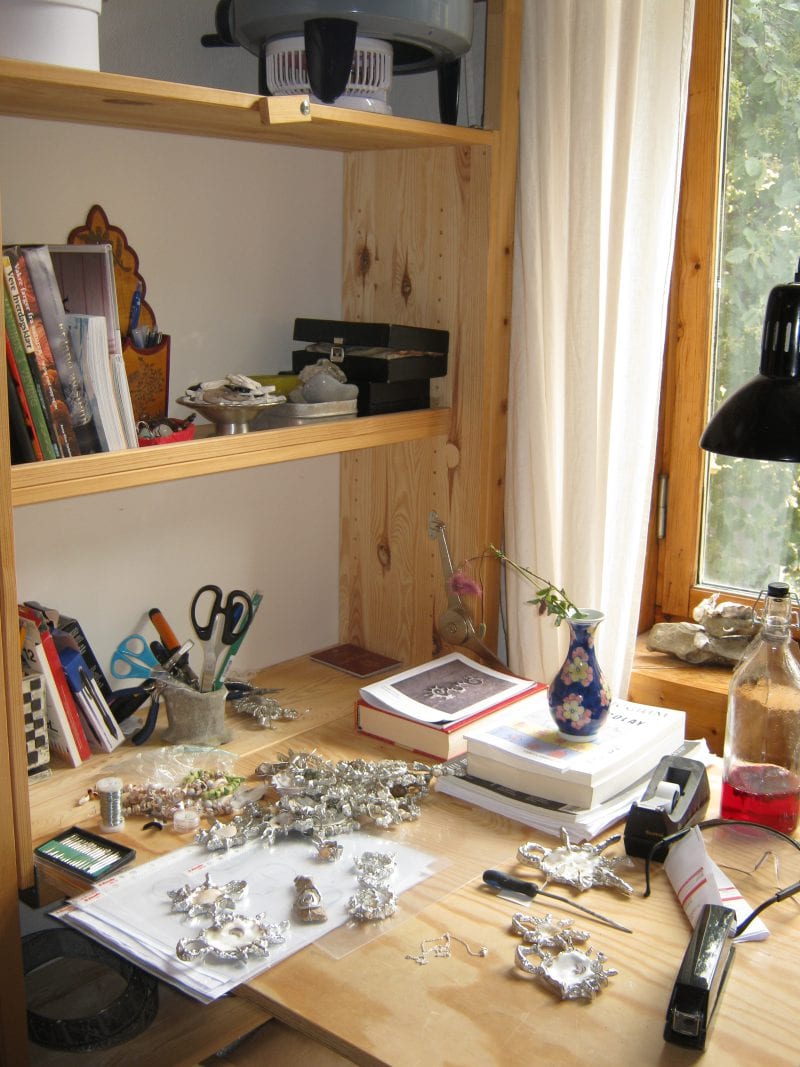

Anniken Øvrebø: I’ve always had a deep need to explore materials. Often, I’ll have a strong urge to use a material in a specific way — wrapping silver around a stone, or combining ceramics with fabric — even if I don’t yet know how. That curiosity drives me to experiment, to think, to play. I love the unpredictability of it. The outcome is often a surprise. When I started, I wasn’t intending to make jewelry at all — I simply wanted to shape pewter or silver around something solid and see what happened. The forms that emerged were beautiful, and they naturally lent themselves to adornment and decoration. Right now, I’m a bit obsessed with wool and carding — I’m in a phase of playful experimentation again, collecting raw materials, testing, discovering. When I traveled in my van, I had just begun casting silver and pewter. I needed to make some money, so I set up a little website to sell what I made along the way. Later, I returned to Oslo to study archaeology and started working at a travel shop to pay rent — which means I have less time to create. But the urge to make things never disappears. It just waits.

NK: How did your experience on the road shape your approach to materials and design?

AØ: A major inspiration was encountering different types of stones, shells, and crystals in each country. Their textures, shapes, and colors were like

small pieces of the landscape, each with its own story. The physical space I had to work in — or lack thereof — also shaped the design. I use sand and clay to create molds, and the quality of those materials changes with the climate. Clay might be wetter, drier, firmer depending on where I am. Even the air — its pH, the humidity — affects how the metal behaves when cast. I sketch out forms directly into the clay, but what ends up being cast is often left to chance. In a way, the land decides what the final piece becomes, more than I do.

NK: What’s your process like—from finding a material in nature to turning it into a finished piece?

AØ: It all starts with foraging — for stones, shells, clay, water. I find them out in the wild. Pewter or silver I usually source from second- hand shops outside the city. Then I melt the metals and create formations in clay, shaping molds with my hands. After the casting, I clean, polish, and refine the object — unless I don’t like it, in which case I melt it down and begin again. The process is cyclical, and very intuitive.

NK: When casting or shaping a piece, how much do you try to control the outcome versus letting nature’s forms speak for themselves?

AØ: I touched on this earlier — it really depends on the casting technique. Dry sand or clay gives more defined results, while wetter clay or ice causes explosions and unpredictable forms. There has to be some control to let the most beautiful part of a stone or crystal shine through — but I also

love when the organic, unexpected shapes emerge. They often speak louder than anything I could design myself.

NK: How do the places you find your materials (like the Dolomites or Oslo’s Østmarka) influence the final design?

AØ: I always try to highlight what I find most beautiful in the material — its color, shape, or texture. The exact origin doesn’t always matter. Some stones carry more personal meaning because of who I was with, or where I was — like near my childhood home. But often, I honestly don’t remember. I just know I found something beautiful, and I want to honor that beauty or have fun with its form.

NK: Is there a ritual or intentional practice you follow when gathering stones or clay from the environment?

AØ: My pockets are always full of rocks. I find them in my jackets, my backpacks — I come home and think, Oh, this one! This is from that hike… or This one’s really cool, but I have no idea where it came from. Some stones come from mountain peaks, others from gravel driveways. I collect them

instinctively — there’s a kind of quiet ritual in that.

NK: How do seasonal changes or weather influence your creative process or material choices?

AØ: The smoke from casting pewter is toxic, so I prefer to work outside. Living in Norway, where it’s cold and dark much of the year, means my casting process is naturally seasonal. Right now, I also have less time due to work and studies — which is a bit frustrating. Creativity always flows more freely when time is abundant.

NK: How important is imperfection or unpredictability in your work? Have you ever had a piece go “wrong” in the process—but turn out more beautiful because of how nature intervened?

AØ: I think this is key to my whole practice. I honestly don’t know what a “perfect” piece would look like. The ones with clean, flawless

lines often feel less alive to me. I love the wrinkled, strange, unpredictable ones. Those are the pieces where nature clearly had its say.

NK: What do you consider your pieces as? Are they spiritual objects, wearable art, or something else?

AØ: I would call them wearable art. They’re playful — for me and for the person wearing them. I want them to spark joy, make someone feel special, or simply notice the hidden beauty in the world. There’s a kind of magic in that.

NK: How do you preserve the natural essence of the materials while transforming them into wearable objects?

AØ: That’s such an interesting question. I actually study a subject called Objects: Cultural and Historical Perspectives on Materiality, which explores how an object’s meaning shifts based on how we use it. Jewelry has always been about communication, status, belonging, and self-expression. Shell beads over 100,000 years old have been found in Africa and the Middle East — proof that personal adornment has always been part of what it means to be human. Natural materials carry symbolic value. For me, an object might mean one thing; for the wearer, something completely different — and that’s what makes it so powerful. It brings a sense of calm, identity, and connection to nature. In a world full of plastic, consumerism, and fast fashion, it feels meaningful to return to the raw, handmade, and unique — to create something that can’t be mass-produced. Sometimes, the only thing that transforms a stone or a bit of melted metal into jewelry is a hole and a string. There’s something childlike and simple in that, and I love it.

NK: Do you think your work helps people connect more deeply with the natural world?

AØ: Yes, I do. My materials — pewter, stones, shells — all come from the earth. They carry their own quiet history. Wearing one of these pieces means you’re carrying a small piece of the natural world with you. There’s something grounding about that. In a world of mass-produced, synthetic things, I think we long for something real. My jewelry invites a slower kind of attention — to notice the lines of a shell, the texture of a stone, the weight of metal shaped by hand. It’s about reconnecting with the materials that surround us, and finding meaning in them.

NK: What advice would you give to someone who wants to start making jewelry in an intuitive, self-taught way like you did?

AØ: Follow your own instincts — always. You’ll feel it in your gut when you’re forcing something too much. It’s like a relationship — it can be challenging, yes, but it shouldn’t be draining. Chase the ideas that excite you. Play. Be curious. You don’t need fancy tools or a perfect plan. You just need belief in yourself and a willingness to explore.