“No man is an island,” said John Donne. Personally, I think there is an island in each of us. Only once in a while, happens that someone wants to reach it. But usually, it is a temporary activity.

We are islands because we are born alone. Or maybe, within a specific archipelago. But no presence in our lives is forever. This transience might be frightening, but it is actually what makes everything possible and open. It allows waves to smooth our edges and people to join us, with the freedom to choose to leave or to return.

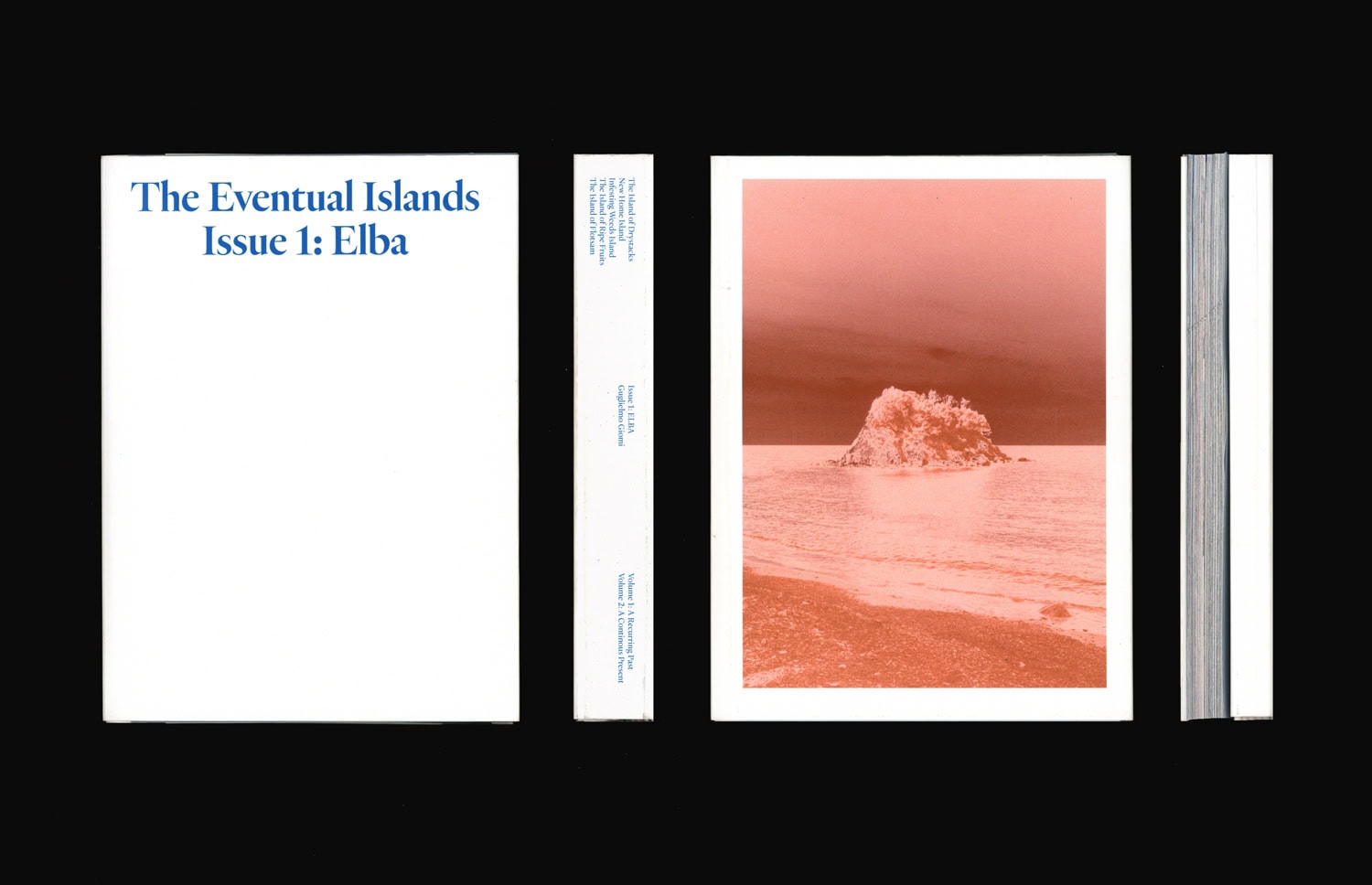

For someone, the island is the destination of a shipwreck. Among them, there’s Guglielmo Giomi. Elba Island has always been his summer home since his childhood, yet something rejects him every September: he will never be one of them. Until one winter, for the conclusion of his Master’s Degree in Photography and Society at KABK (The Hague, NL), he decided to find out why.

He started with the idea of the island because, he tells me, “when you have to study a phenomenon, you always examine an isolated element of it”. Like in a laboratory. But he didn’t expect to end up isolated himself. COVID-19 broke out while he was there, and took the study to its extremes. He found himself on an island within an island. And the research about the abandoned winter of seasonal places risked turning into the tale of the year in which summer never came. The island had never seen such an empty May. Yet 2020 made, even this, possible.

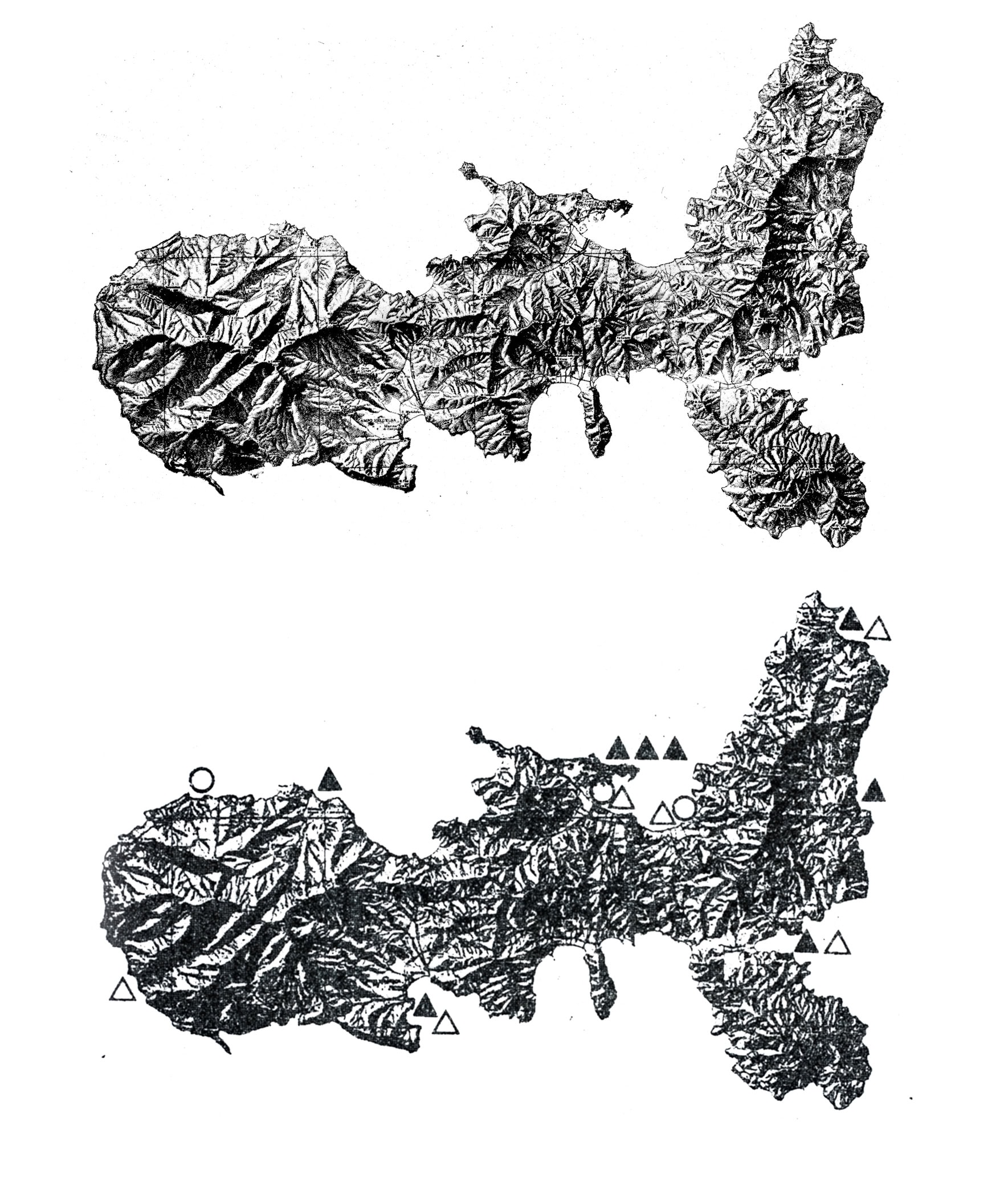

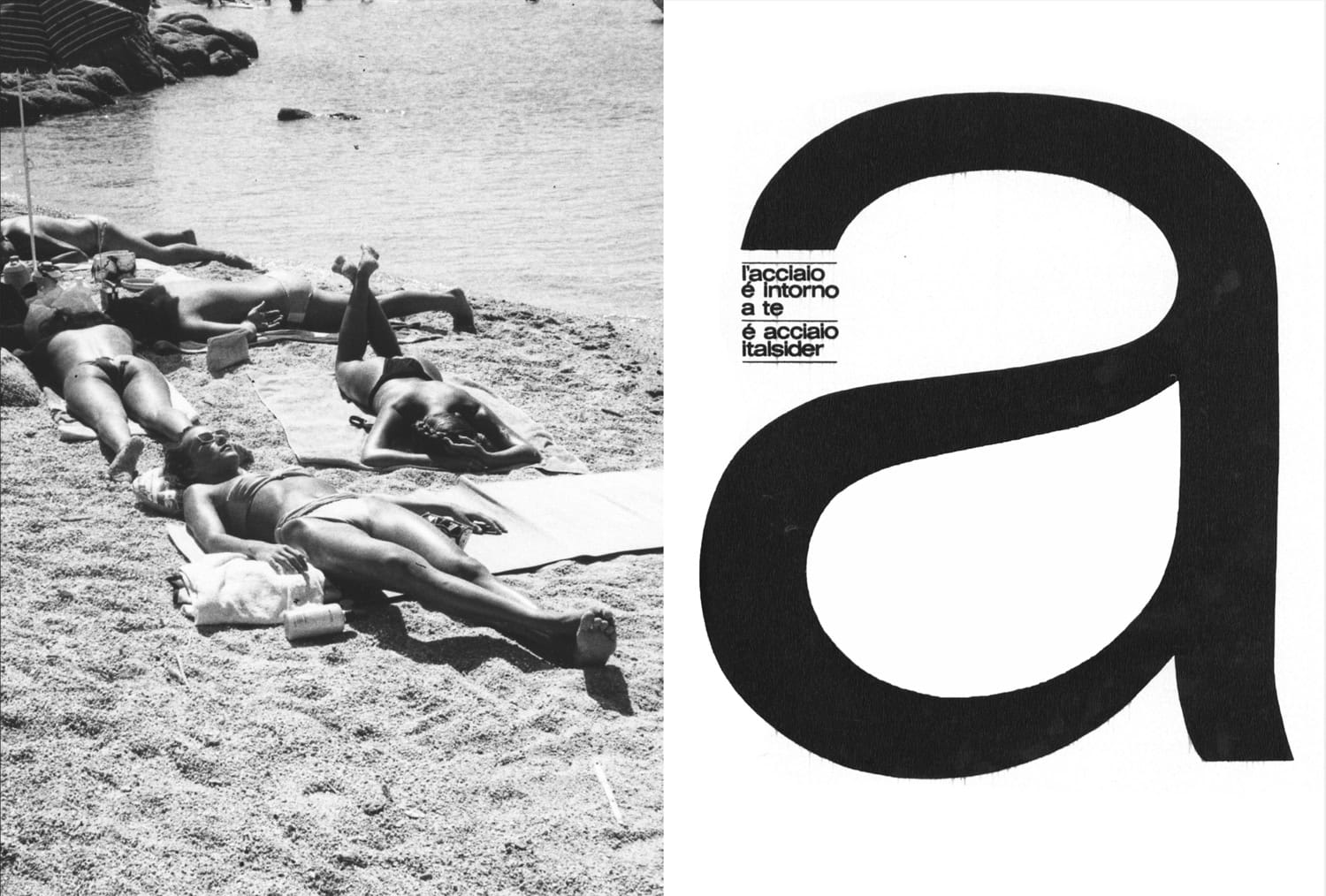

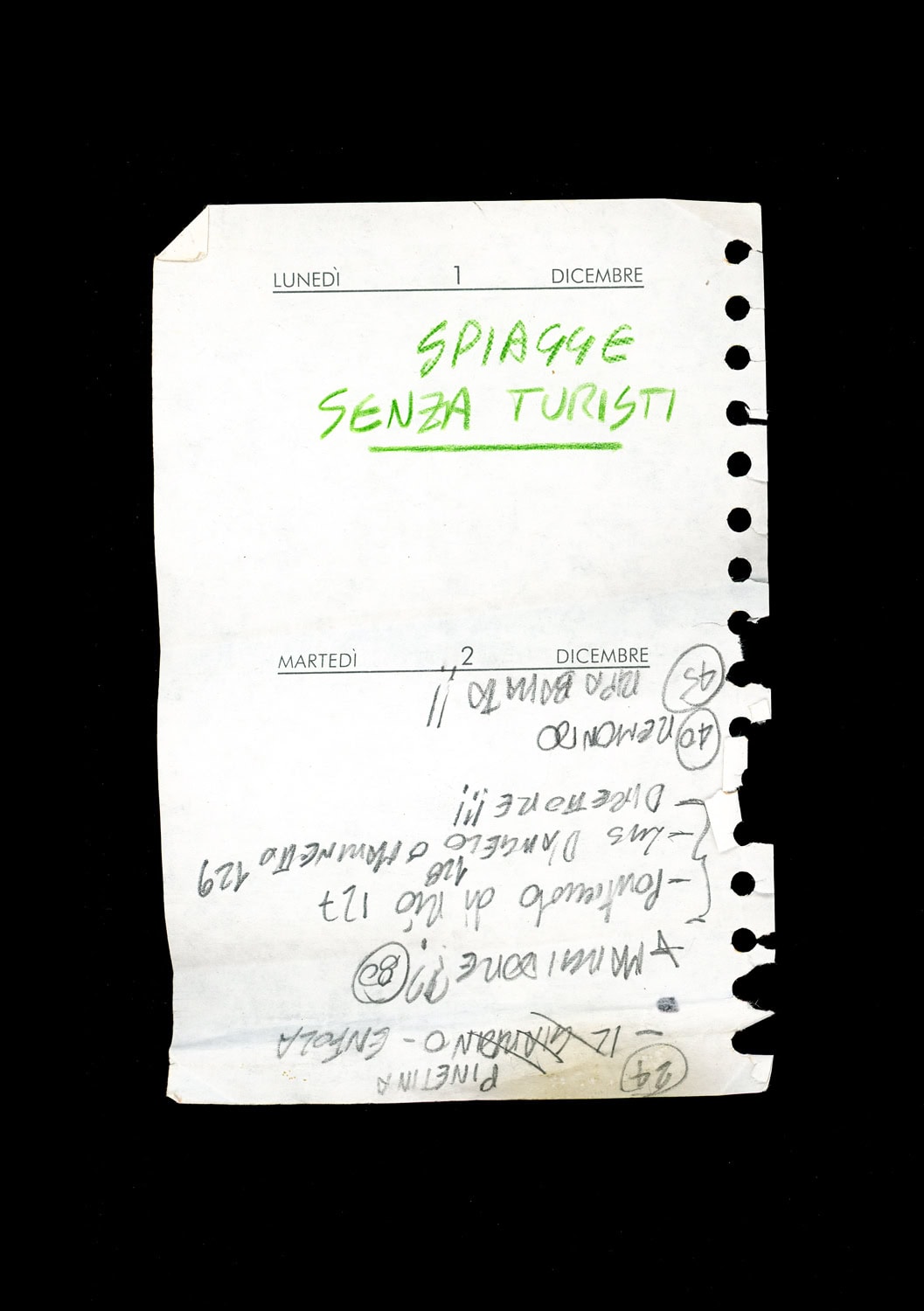

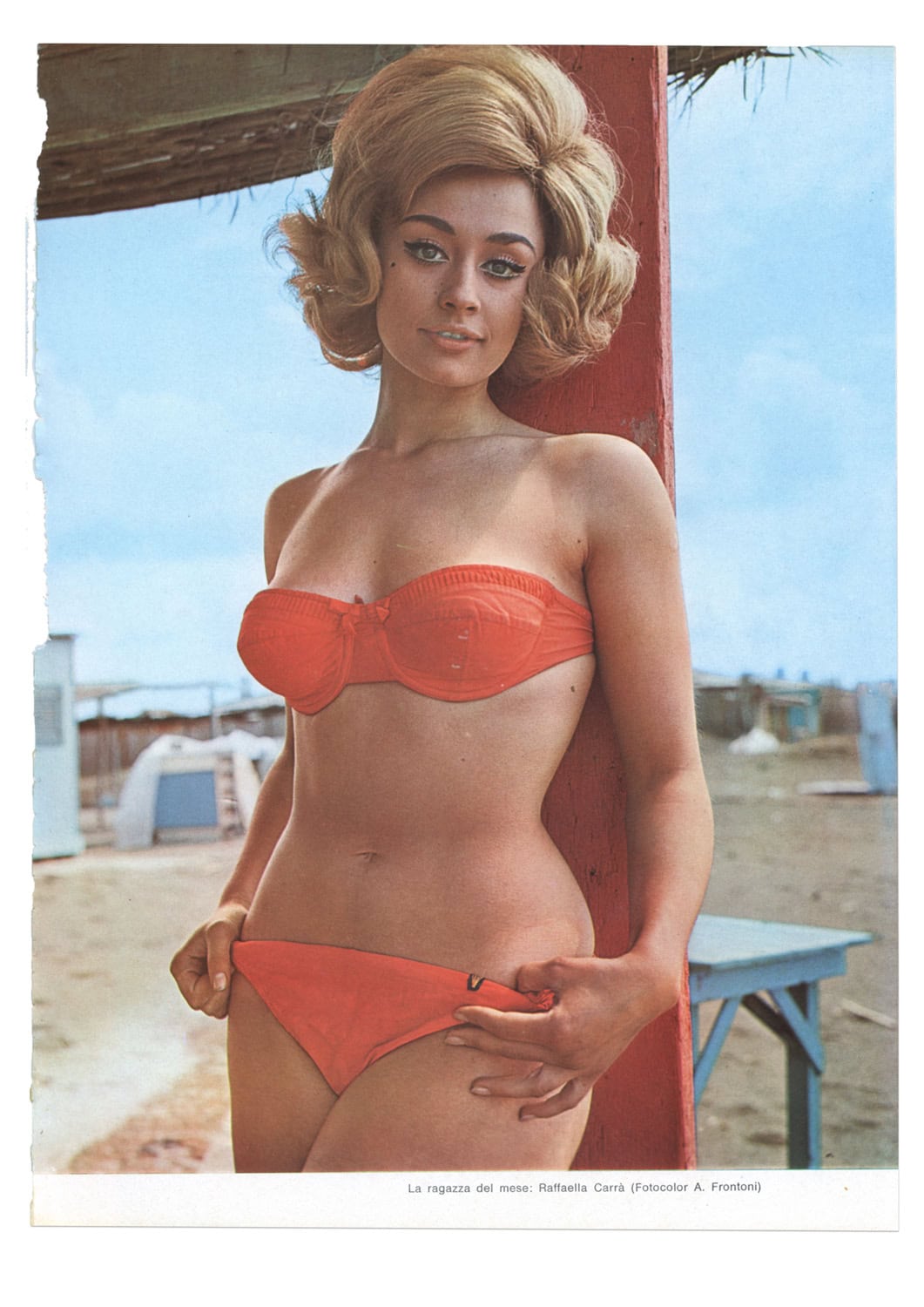

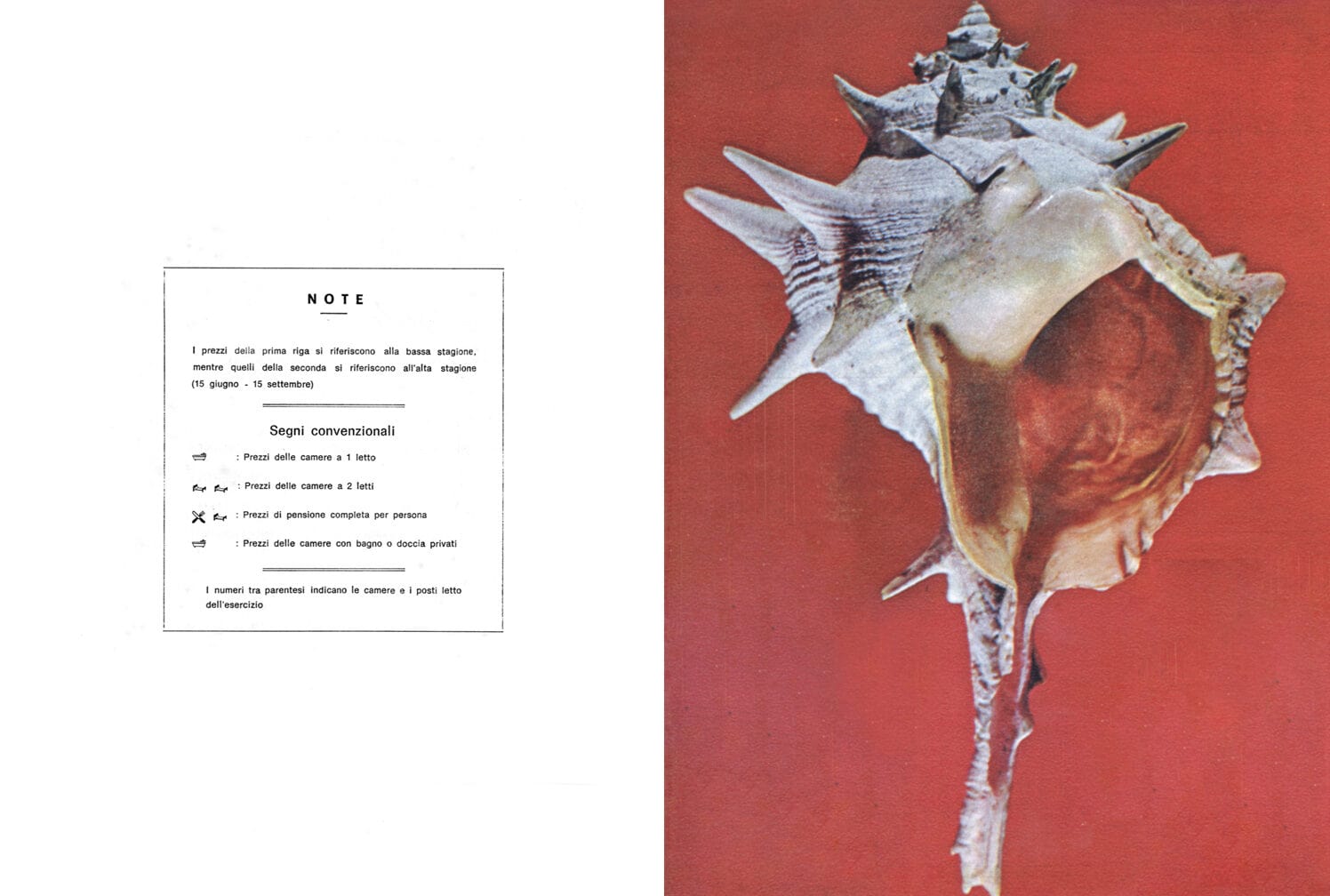

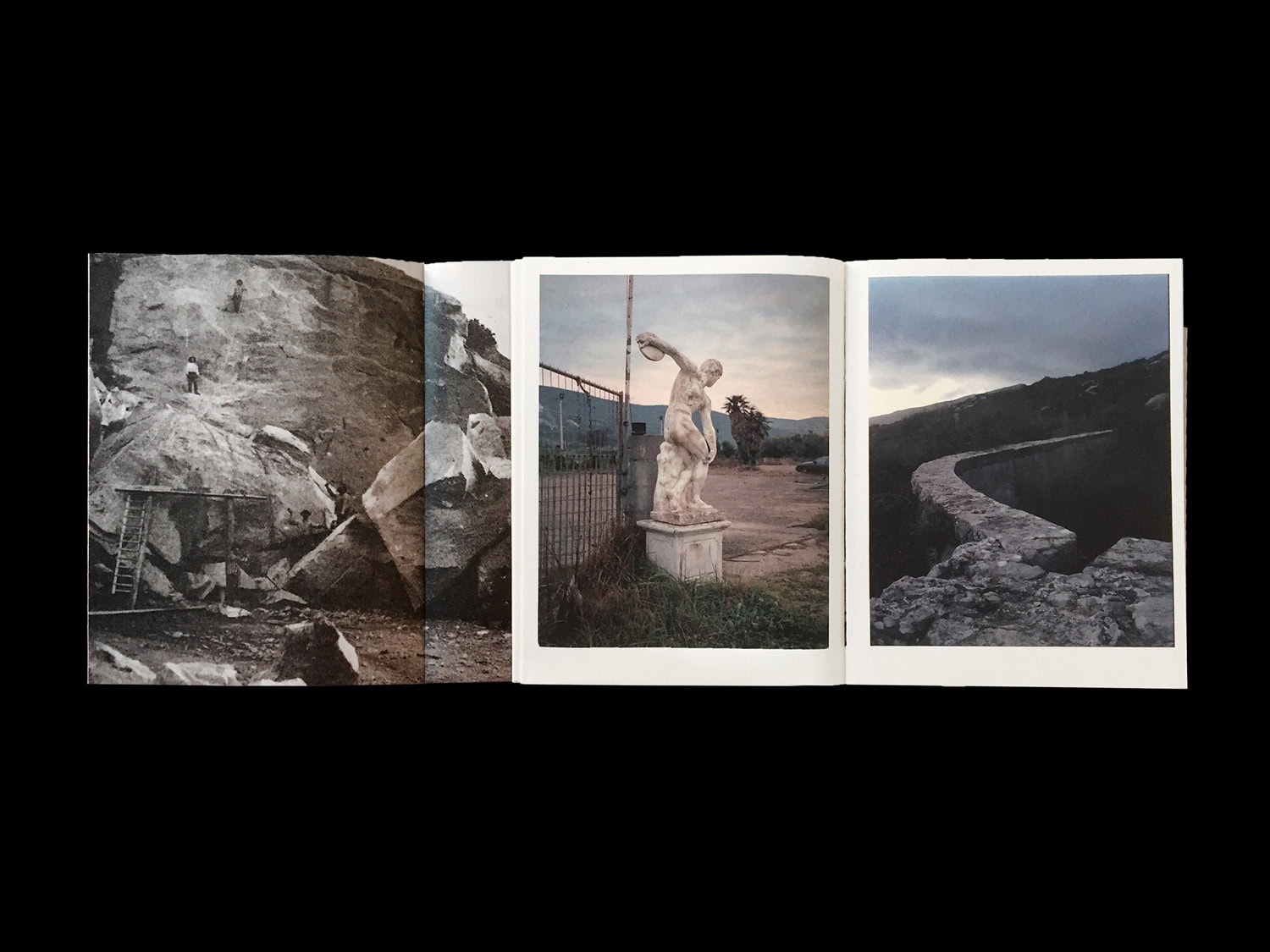

Guglielmo wanted to understand what happens in tourist destinations when everyone leaves. If they still exist, and in what form. But above all, what is the relationship between the image that everyone has of them and the one on the flip side of the coin. With an almost ethnographic approach, he emptied the archives to redraw the boundaries of an island that only exists in summer, while capturing its temporary nature during winter. But his research wasn’t only an iconographic study of old postcards. He personally took part in the life of the island, by meeting its quiet community and embodying their ephemeral movements. The collective process was essential to find a path that could resonate in the mind of each inhabitant, making Guglielmo part of that common yet unexpected vision.

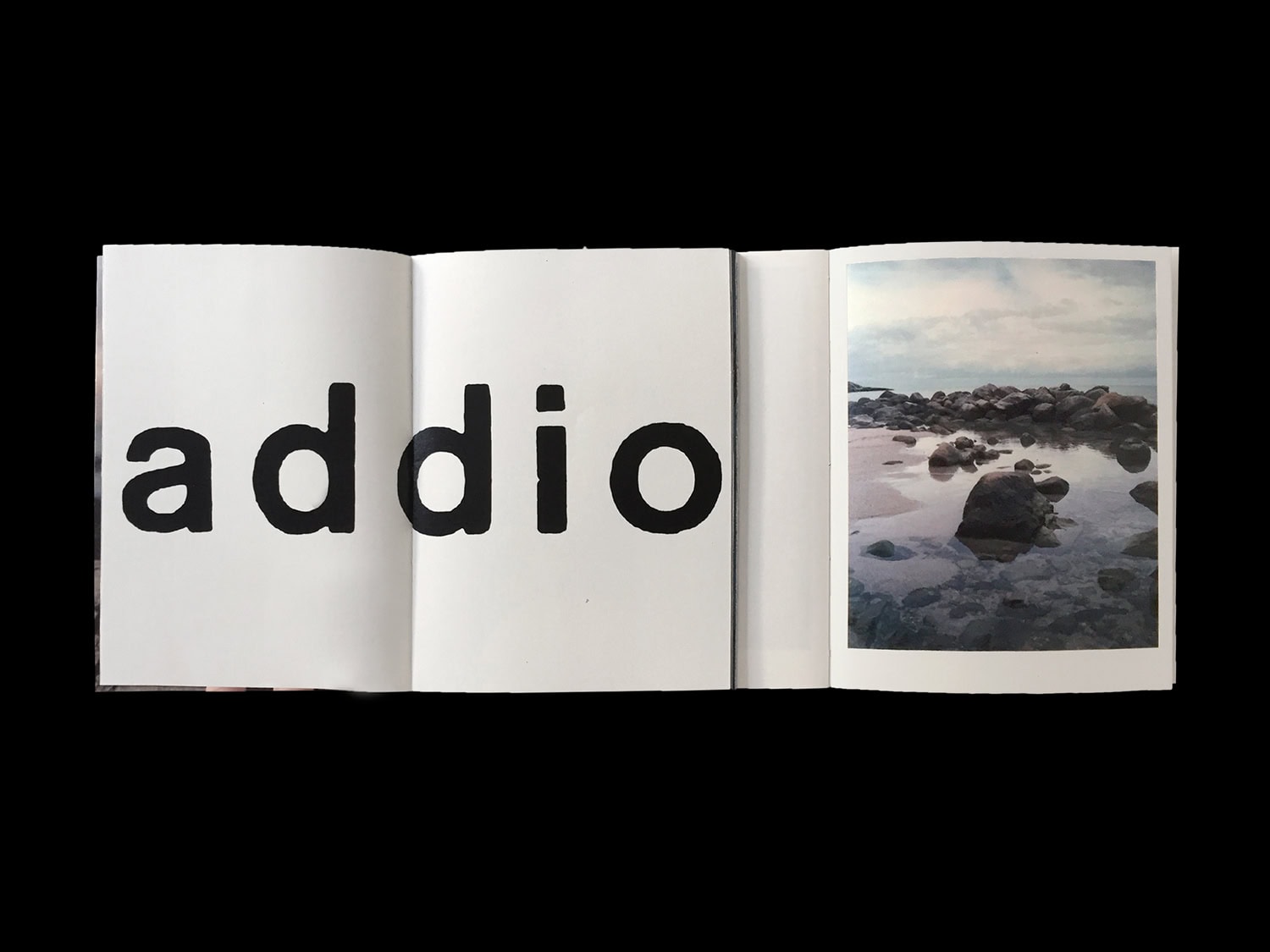

The research was summarised in two visual narratives that meet in a non-linear manner. The first is called “A Recurring Past”, and refers to the commodification of the island typical of summer. The second, “A Continuous Present”, refers to the forgotten vision the locals have of it during winter. Crossing them together, he tried to draw a new map, in which he still doesn’t know where to place himself.

With an almost anthropological work, he managed to reconstruct the identity of a place through the deconstruction of its narrative stratifications in time and space, defining a whole set of unprecedented coordinates. Although his gaze can now look beyond, for him the island continues to be a mystery. Even now, he doesn’t know whether he is an affectionate tourist or a temporary inhabitant.

What is certain is that he keeps coming back. And every time, the island is there. Alone, but reachable. Like of all us.

The Eventual Island (2020). Words by Guglielmo Giomi:

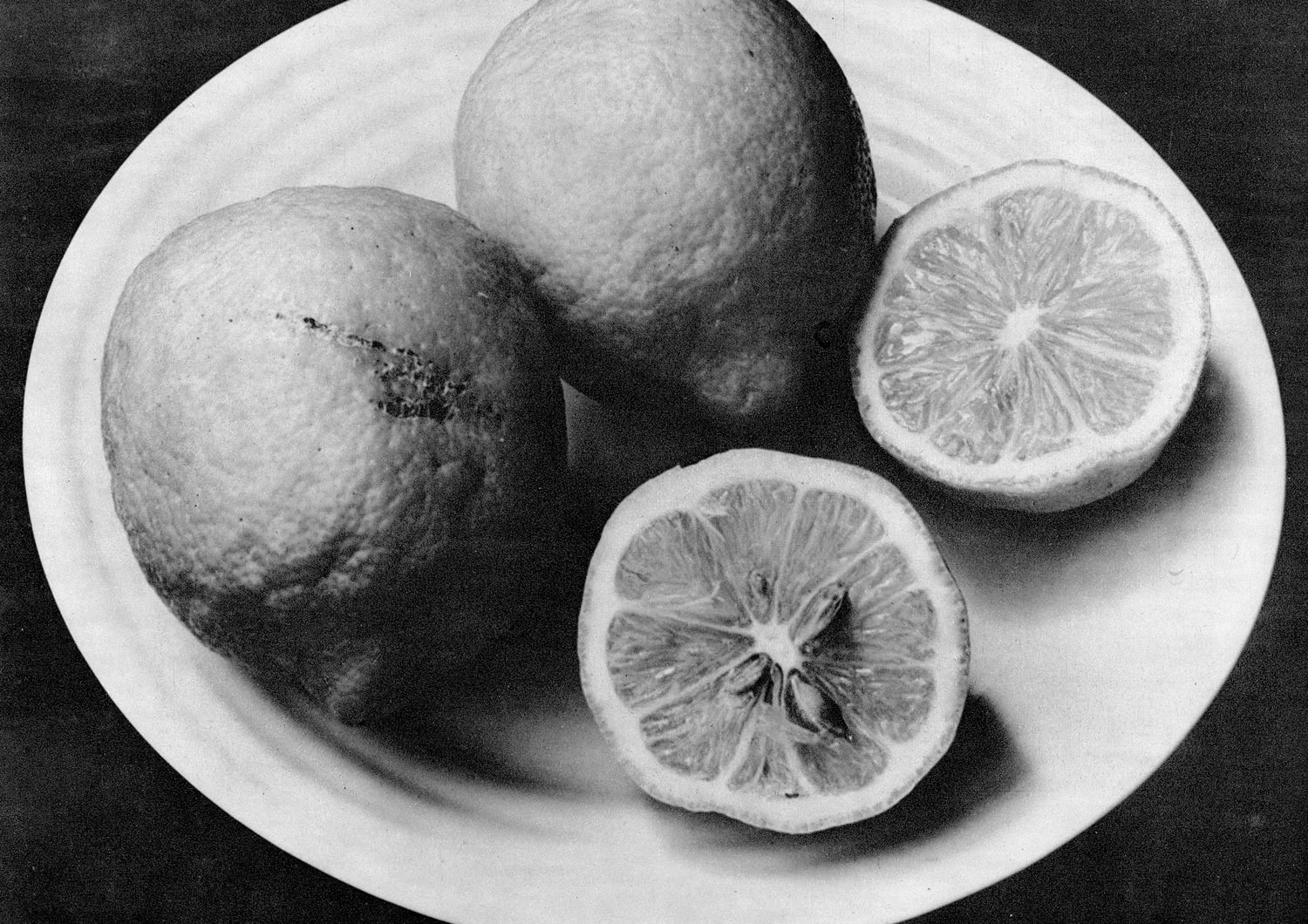

“The Island is the place where I spent my childhood and adolescent holidays. In the past 60 years, the Island’s economic system has shifted completely from agriculture to summer tourism. Each winter its population gets drastically reduced, shops close, workers get unemployed due to an absence of winter jobs, and, according to many residents and tourists, the Island goes into hibernation for about six months. Throughout my life, I’ve done nothing but perpetuate this vision. In the winter between 2019 and 2020, I returned to Elba Island and decided to live there during the cold months, trying to negotiate my vision built over the years and exploring the neglected and exploited spaces in it. Deserted by most of its supposed inhabitants after a recurring catastrophe, the Island’s environment appears to be in a state of forgetfulness. Through photography, I tried to “abandon” the supposedly known Island in order to “inhabit” a new one made by elusive encounters, getting dirty with the materiality of the environment and guiding the author through a whispered utopia. By addressing the contrasting relationship between touristic exploitation and perception of the environment, I confronted the deepest frictions between space and place. On a deserted beach some children start building houses, on the mountain a family fixes a drystone wall after a fire, two masked figures climb a locked gate to get some oranges from a closed hotel’s garden. What is left abandoned in the space of exploitation during the winter became inhabited by a quiet community whose traces are visible through the embodiment of certain movements and paths. Looking at the Island from a distance will likely give the appearance of absence, but what you will find with a closer view are possible futures in the middle of the sea: the Eventual Island.”