I’m the kind of person that outside InDesign and other grid systems starts to have panic attacks. That’s shortly the reason why seeing Erik Kessels presenting his book ‘Failed it!’ in 2018 was kind of mind-blowing. He showed us images covered by their photographers’ fingers, blind balconies and wrongly assembled models on huge advertising billboards. I still remember them exactly because they weren’t what I expected, and that’s the point: imperfections are always remarkable.

Erik is a Dutch artist, designer and curator – but I don’t think what he does can fit into a proper existing definition. Just to give you an idea, one day he went to work dressed up as a chicken and, briefly after that, he got fired. That’s how he ended up founding his own creative agency, with the other “chicken-colleague”. Today there’s a KesselsKramer in Amsterdam, London and LA. But Erik’s personal research goes further and questions the boundaries of contemporary photography, by reversing its very nature. He recently held a workshop titled ‘Complete Amateur’ at Micamera (Milan), and Giulia Zorzi kindly put us in contact with him.

Someone would call it post-photography, referring to the evolution of the practice after the digital turn and the Internet era. As it happens with others “post-words” (e.g. post-truth), it’s not clear wether there’s really something new going on, or it’s just a way to take distance from the past. What’s your personal definition (and view) of post-photography? Is it going to find its way into the chaos?

The role of photography has drastically changed over the past few years. An image isn’t so much there to be kept anymore, but to be shared or used for a very short time. The images we make ourselves and share online drown into the sea of a trillion of other images. This changed the distance between our own photographs and the ones made by others. Artists today are surrounded by the images of others, and they use them by re-appropriating them in their works. You don’t have to own a lens anymore to be a photographer: nowadays, your eyes are enough.

Initially, photography was considered a new form of ready-made. Indeed, reality was already there, waiting for someone to change its meaning. Today, something similar is going on, but on a different level. Everything has already been represented and there’s no point in reiterating it. However, we can still select and recontextualise the existing materials. Your work is mostly based on this re-appropriationist practice. How is it changing, from flea markets to social networks?

Authentic documents like photographs and family albums are slowly disappearing from flea markets. The Internet and social networks are nowadays the “new flea markets” for artists and visual archaeologists to explore. It’s a thick forest to go through, but by carefully searching, it can be very rewarding. In the end, it is all about the story you’re able to tell with a frequence of images and not about the provenance of the images. I don’t care where I’m finding the images as long as I can make an interesting narrative out of them and I’m able to tell a new kind of story with them.

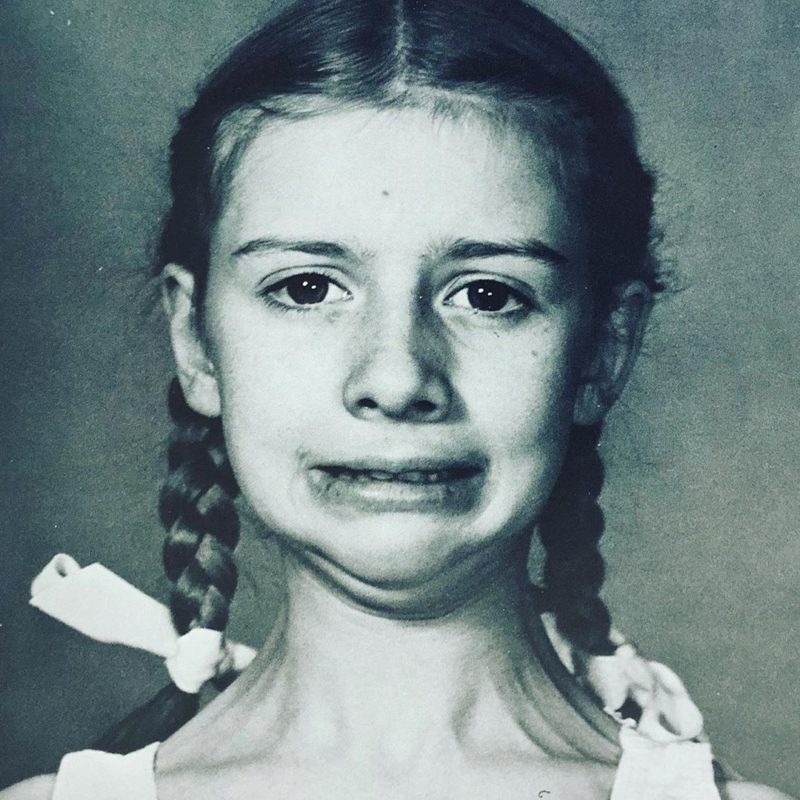

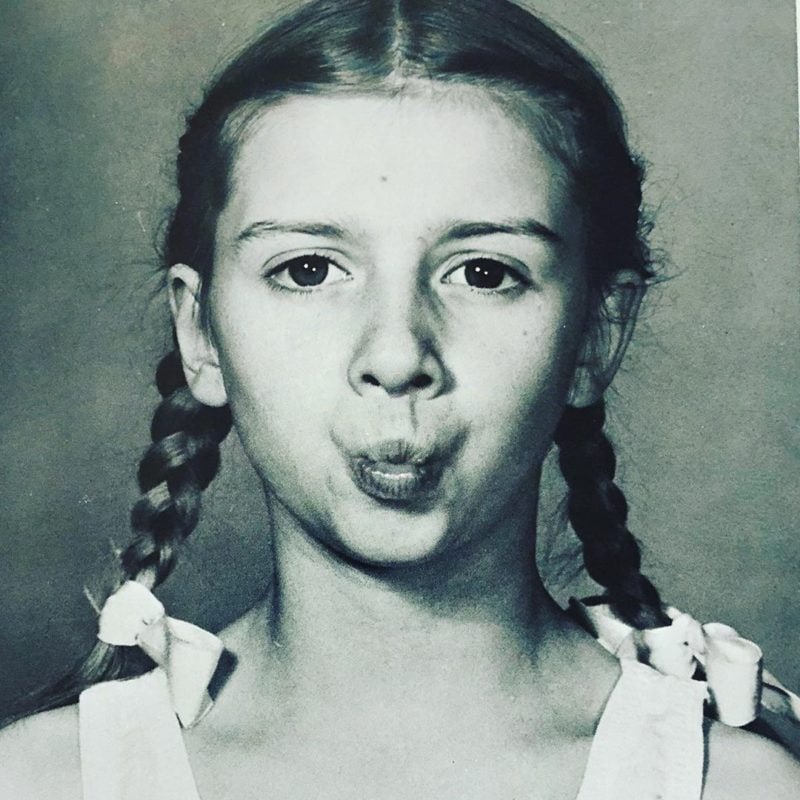

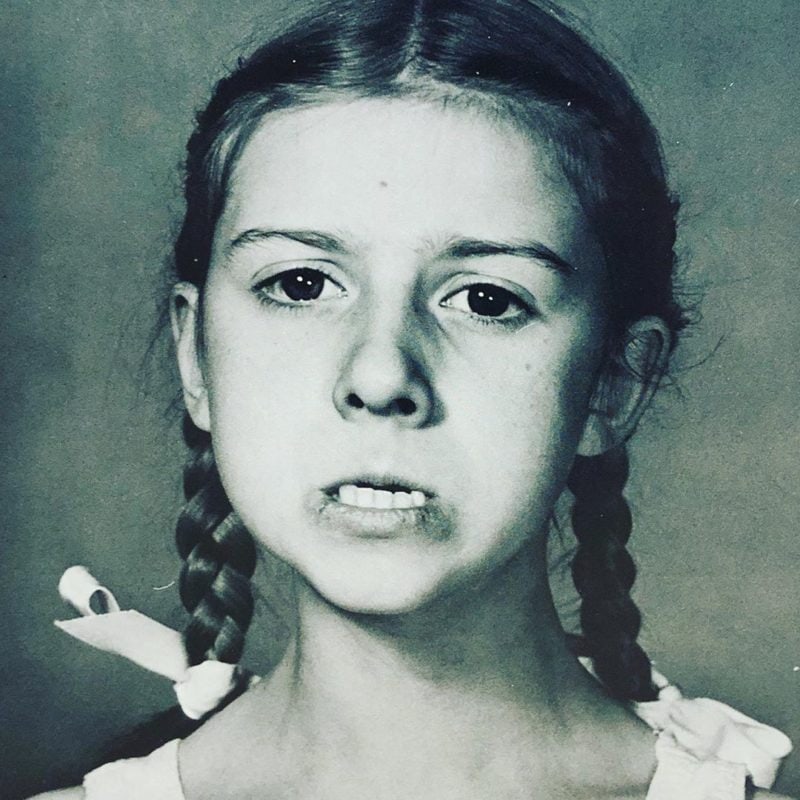

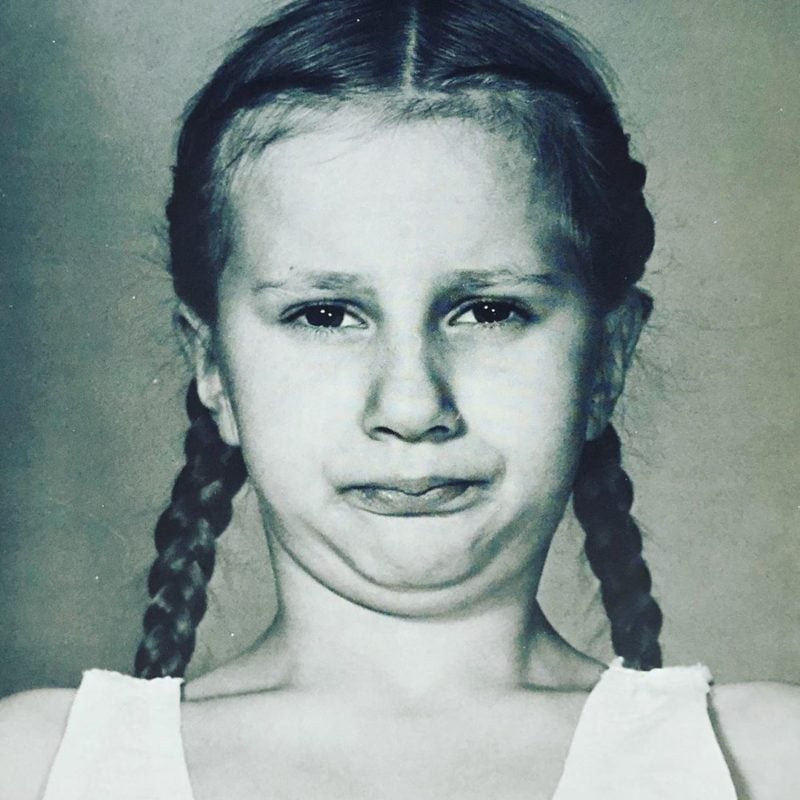

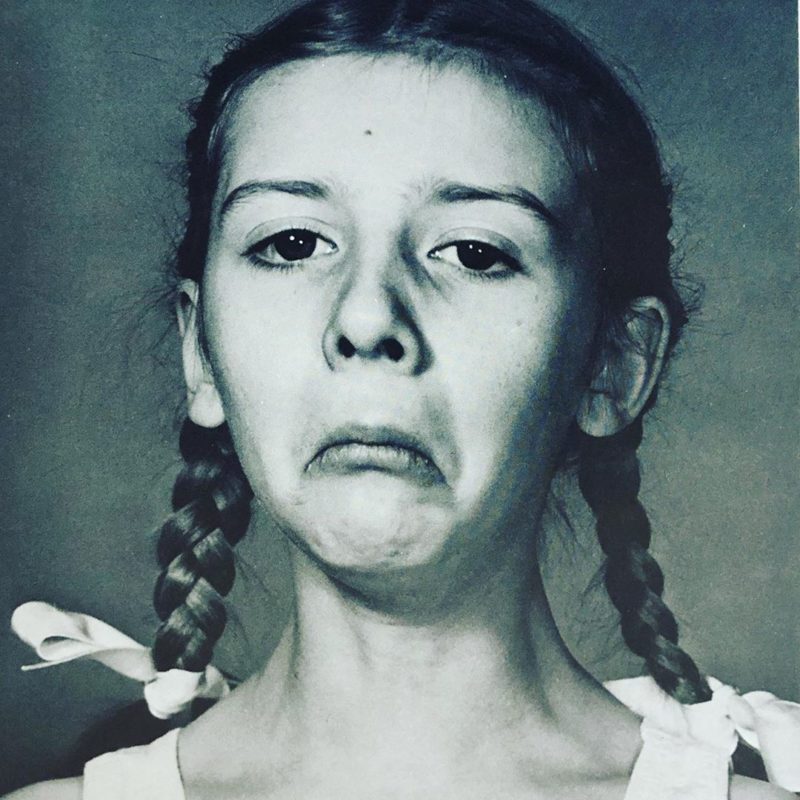

In your series ‘In Almost Every Picture’ you address the attention on the repetition process. There’s something touching in it, as in the case of Valerie’s wet portraits shot by her husband. Do you think is something that could still happen today? Do we learn something from repetition or it is more related to a disposable culture?

I think that this can be still possible today, but I have to say that we lost a big part of our naïve way of looking and taking pictures. Everyone has become pretty professional with his camera device. The series of photographs that I’m really interested in are often made over a certain moment, and the people that shot them didn’t know they produced a fabulous sequence of images over time. Nowadays a series of photographs is already prepared upfront, or well thought and made up from the beginning.

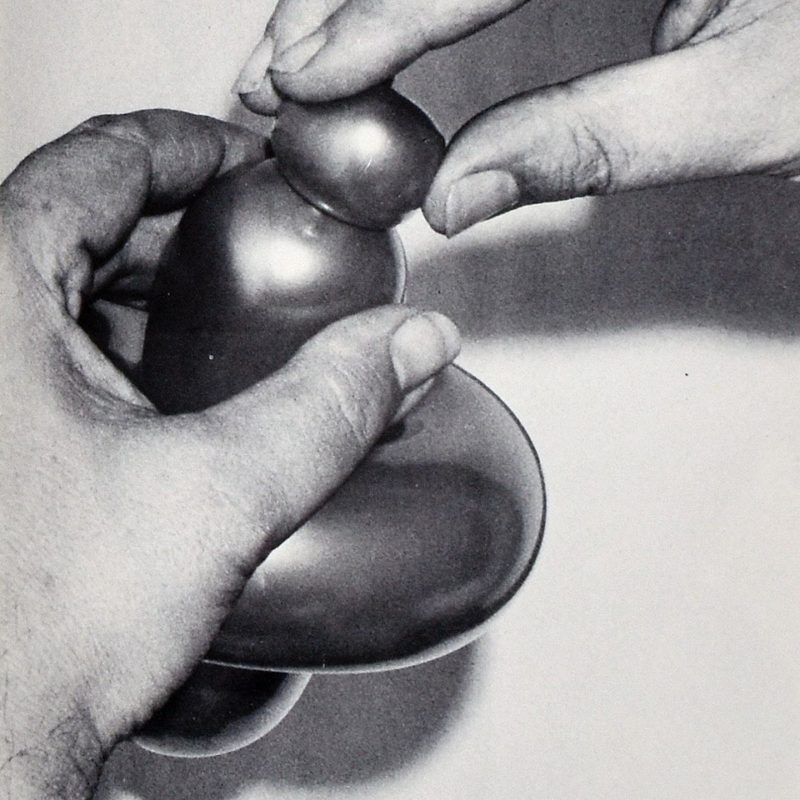

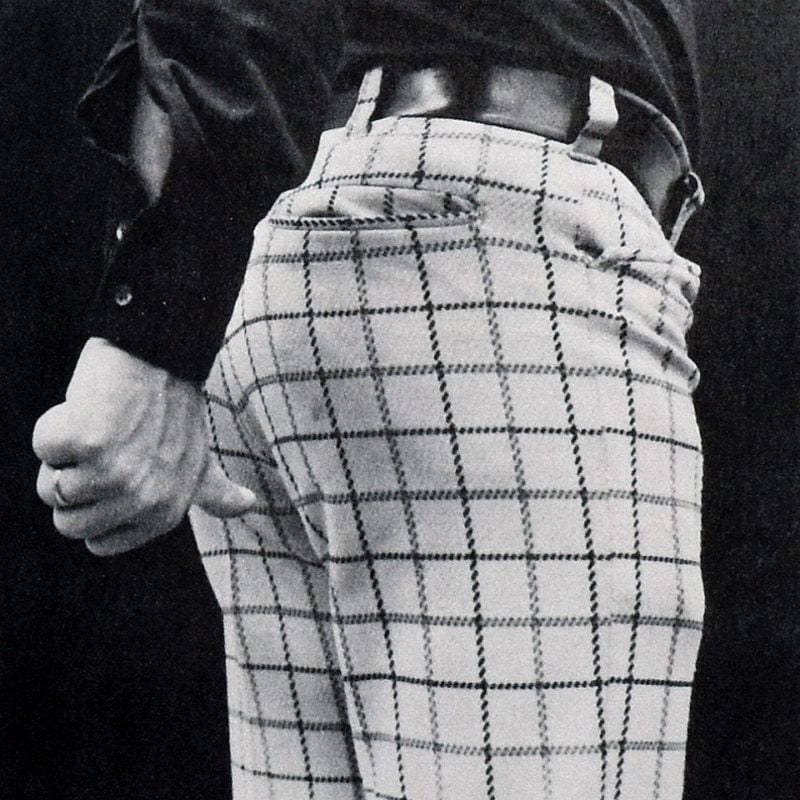

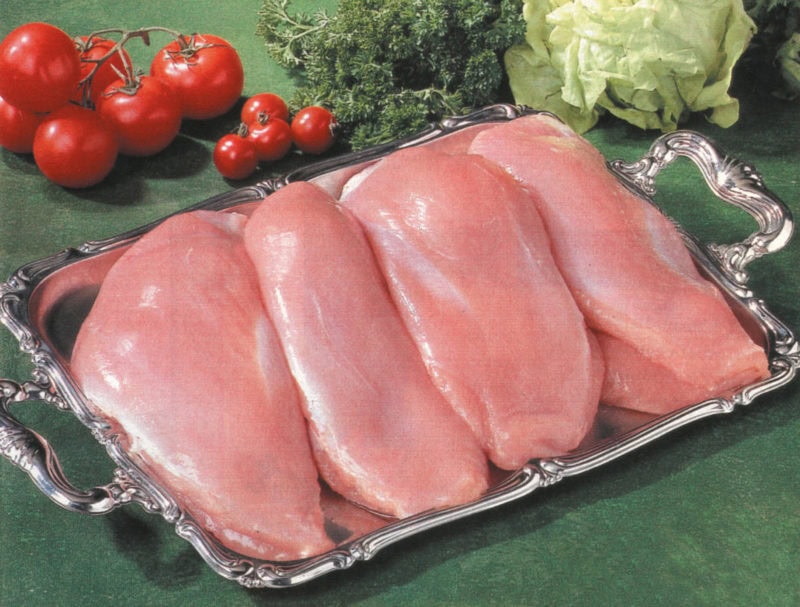

‘Useful Photography’ is another of your masterpieces. It could almost be defined as a pornographic process, in which you get photography completely naked. You undress it from its aesthetics refinement and metaphorical layers, taking it back to what it simply is – and what it shows. Is that a way of resetting a saturated practice?

This is indeed the process we follow. There are millions of diverse photos, which are used daily for a purpose: photography with a clear function. Think of photographs from sales catalogues, instruction manuals, packaging, advertising brochures and the Internet. Published photos, mostly without the makers names mentioned. These images are often, because of their function and the context they’re shown in, totally overlooked. By taking them out of their context and placing them all democratically together in a new context, the images become visible again. Organizing them from the large clutter of images we live with today can sometimes hold our interest in them for an astonishingly time longer.

Today society asks us to perform. There’s no space for failure, and everything has to be beautiful and functioning. ‘Highly Uncomfortable Photo Books’ questions this principle and moves us outside our visual comfort zone. In your opinion, is there a chance of changing society standards through a kind “visual rehab”?

It would be euphoric to think that by changing some visual standards, the standards in societies would follow. But it’s healthy that artists are at the forefront of trying to do this. Artists are people that think and operate (metaphorically) in the fringe of things. Here they find interesting material that confronts or shocks mainstream viewers. Everyone drives on the same “visual highway”, but there’s a lot of unknown images to explore while you start driving off track or on very small side streets. These roads are bumpy and muddy, not beautiful and dis-functioning, but – in the end – rewarding.

Social media platforms like Instagram seems to amplify the conformist production of “perfect” images. Everyone is his own entrepreneur – having a business profile and forcing photography to be staged and filtered. If there’s still something true, it lies under a lot of hardly accessible layers. Why are we so scared of reality?

Reality is naked, dirty, dark and brutally honest sometimes, that’s why we don’t dare to face it and share with a lot of other people. Instagram turned into a platform of personal propaganda, where people show themselves in their best and most polished way. All these “mini” propaganda channels are totally “egocentric” and don’t collaborate together. For me this is a fantastic phenomenon to look at and to analyse from a distance. The opportunism that same people use to advertise themselves is fascinating to look at. Perfection and picture perfectness is a component of this. Instagram is your own personal shop window, where you display everything in the best possible way, to give a perfect impression of yourself towards everyone passing.

‘In Almost Every Picture #15’ is a collection of found images in which “A woman censored the images of ex-girlfriends of her husband as if she wants to say: he’s mine”. There’s no way to know more: the mystery is almost magnetic. In an age in which everything as a caption, this unexplained layer is what still makes sense in photography. Do you prefer looking for it in old family albums or making it up by shooting your own photos? Is there a real difference?

Again, I think that when you would make a series of images with a certain idea in your mind, the outcome of it would be totally different from the ones that you find and re-appropriate. There’s a quote saying: “You don’t take a photograph, you make it.” People with a camera know really what they’re doing. But the real amateurs amongst us are kind of blind for this. They often forget about what they’re doing and have such a deep fascination that they’re not into “making a photograph”. These works they produce, often without knowing it themselves, are almost an act and have a strong performative character. I’m hunting for these stories, never know what to find next and this gives me, needless to say, a lot of satisfaction.