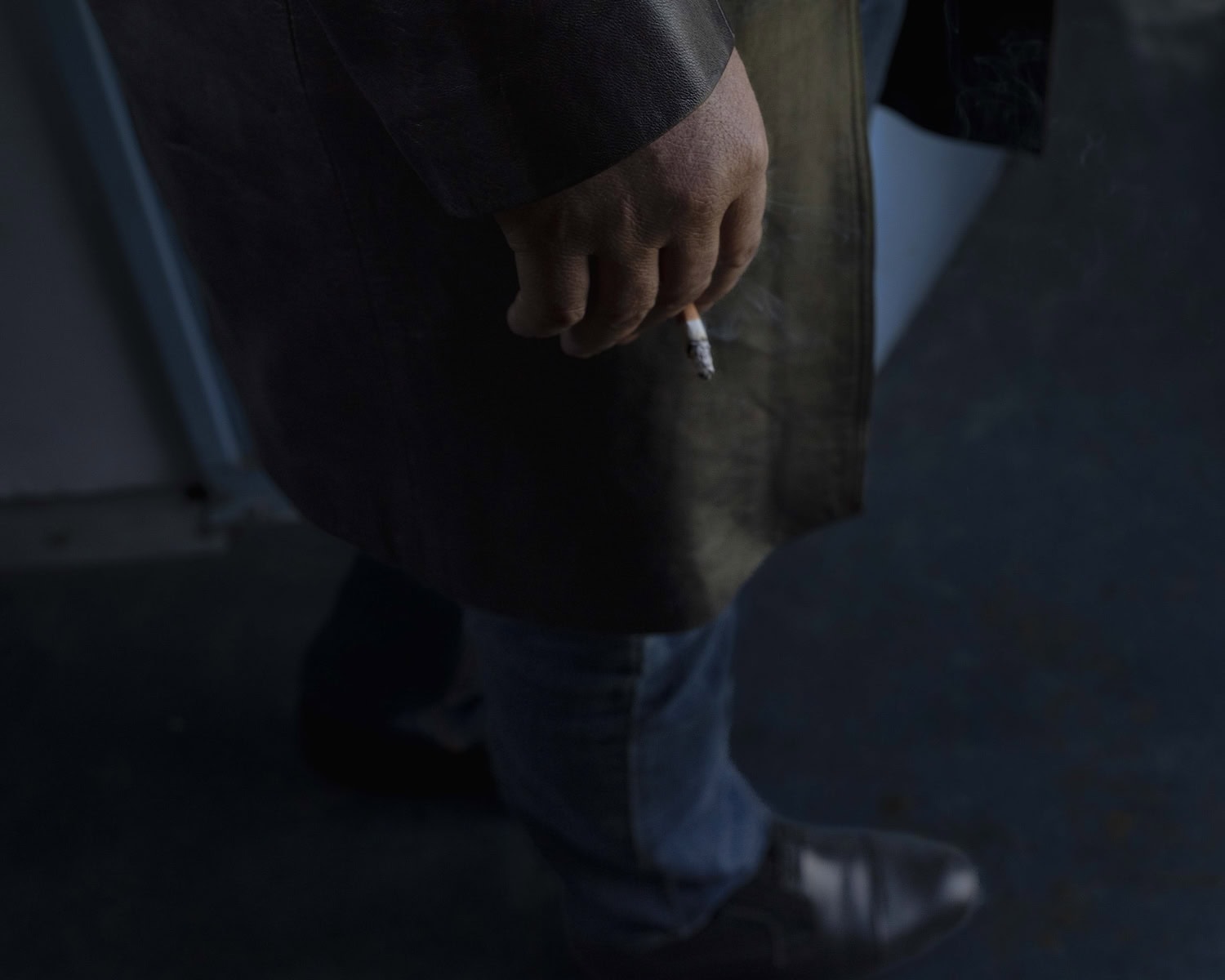

In December 2022, something magical happened in Morocco. The country was enveloped in a dreamy haze, a state of hopeful waiting and joy, that seemed to permeate every corner of the nation. The Moroccan soccer team had made history: the “Atlas Lions” were the first African team to reach the semifinals in the World Cup. Their consecutive victories against Spain first, then Portugal, propelled the Moroccan team to the heart of the soccer world. But it wasn’t just about football–it was about something much deeper. The feeling of hope and joy that swept the country transcended all social, economic, and political barriers, touching both new and old generations, whether they were in bustling city streets or the windswept desert dunes. The sound of “sir sir sir” echoed throughout the land, lifting spirits and inspiring all who heard it. But even when the team faced their first defeat against France, the people of Morocco refused to let their spirits be dampened and continued to embrace this oneiric moment.

Anna Prudhomme: What first got you into photography?

Giovanni De Mojana: Let me start by saying that I wouldn’t be able to pinpoint the exact moment when I decided to become a photographer because it’s not a decision that happens suddenly; rather, it’s a long journey… a journey that never really ends. However, there have been several experiences that have marked this path. I was born in Milan but after completing school, I went to study filmmaking in Berlin. As part of the course, each student was required to create a final short film, and many of my peers sought my contribution as the Director of Photography, which was flattering but also helped me understand that I might have a different perspective on things. If I have to identify the key moment, I believe it occurred after meeting documentary photographer Francesco Anselmi in 2016 which I assisted on various projects. That year, we went to Athens together to document the memorial event for Alexis Grigoropoulos—a 15-year-old boy killed by the police which resulted in the 2008 Greek riots movement. I was only there to film and wasn’t taking photos but seeing Francesco’s work in the evening right after the event had a significant impact on me, so much so that I decided to start taking photographs rather than film. Through this experience, I started seeing photography in an entirely different light, and my interest grew stronger, surpassing my passion for filmmaking. Athens was surely the beginning. But I believe I made the definitive decision after my experience in the United States in 2018 where I worked as Francesco’s assistant on his project Borderlands which was about life in the shadow of the wall that separates the states from Mexico. When I returned from America, I went to Oman and couldn’t help but capture everything I saw. It was perhaps then that I told myself it had to continue.

AP: What is your approach to photography?

GDM: In my opinion, images are the ideal practice of self-expression, way better than words. I rely on this visual language to convey my thoughts and emotions to others. For me, the photographer’s job is not about copying reality but essentially about capturing a particular perspective, which is nothing but the projection of one’s unconscious. In this way, we discover that reality gains more depth because it can have multiple expressions. This fascinates me: capturing what lies behind the images and only emerges when we look at a well-crafted photograph. I thus try to create a subjective photographic representation that considers aspects of the past and present, focusing on how individuals interact with their surroundings.

AP: How do you perceive the significance of the connection between a person and its environment?

GDM: It’s an inseparable relationship! My interest in an individual is closely tied to the context in which they find themselves and the action they are undertaking. This connection between subject, place, and action is what makes a photograph meaningful to me. Italian writer Gianni Celati said, “A photograph is not a representation of the world, nor is it a copy of the visible, but is precisely a measuring meter made to imagine and understand what is outside the frame of the visible, outside of ourselves”. This thought constantly accompanies my photography. When I frame an image I know that, necessarily, I’m looking for something that lies “behind”, and I ask myself whether the becoming that I’m immortalizing at that moment is really my vision, or instead a more superficial and stereotyped concept of reality. Of course, at the precise moment I’m taking the picture I cannot say that. Because the way we perceive things is generally generated at an unconscious, spontaneous level, over which we have no control over. For this very reason, I think that making photography and in fact more broadly art, makes it necessary to break out the controls of everyday life and false certainties.

AP: How does that play out when you are reporting abroad?

GDM: During my travels, I have been driven to discover the “truth” of a certain place by literally chasing after the images, letting myself be guided and transported by them…as if they were boats that allowed me to navigate a complex and varied reality. I am walking through the streets of Istanbul or wandering through the depths of a Burmese forest when an image appears before me with all its dramatism. If we understand the word “drama” in its first meaning, “action”, then we realize it is in the becoming that things reveal themselves. It is the photographer’s eye that must be able to capture that particular movement that helps us guess what lies behind reality. When I shoot, I have the constant desire to disappear from the scene and be invisible. Being able to grasp the close relationship between inner and outer landscape through the mimicry of not only people, but also animals, or through the very shape of the landscape, always pushes me a little further into reading this world I don’t know.

AP: Could you talk us through how and why you made this series entitled Sir Sir Sir?

GDM: I was fortunate to be in Morocco during the Football World Cup 2022. When I left the agency where I was working as a staff photographer, I decided to embark with a lifelong friend of mine on a two-week trip to Morocco. Except for the first few nights, we had decided to go day by day. The trip coincidentally (or intentionally) coincided with that momentous occasion, and our days there were deeply linked by the Moroccan team’s achievements. Nobody could have predicted Morocco’s victory against Spain and Portugal, but it eventually happened, and it was great! In Tangier and Marrakech, we were able to partake in the fans’ celebrations. Until the day we left, our whole trip was connected to this feeling of hope and joy mixed with fear that ran through the country. That feeling was palpable, transcending social, economic, and political boundaries, resonating with both the younger and older generations. Whether they were in the lively city streets or in the windswept desert dunes, the sound “sir sir sir” (meaning “go go go”) echoed throughout the country, lifting spirits and inspiring all who heard it, including us. Despite the team’s defeat against France, the Moroccan people refused to let it dampen their spirits and embraced this once-in-a-lifetime moment!

AP: What is the next project you’ll be working on?

GDM: In September 2023, I started the first part of a very ambitious project that, to be completed, still requires a lot of work and some travel. In the meantime, I would like to delve into a topic that is dear to me by travelling in Italy to photograph villages that, after almost becoming extinct, are slowly repopulating. We are going through a historical phase in which the need to repopulate and take care of the mountains becomes increasingly clear, as life in the city alone now seems unsustainable. This movement towards the mountains is defined by a neologism “metro-montagna” and encompasses the purpose of bringing together these two seemingly incompatible realities.