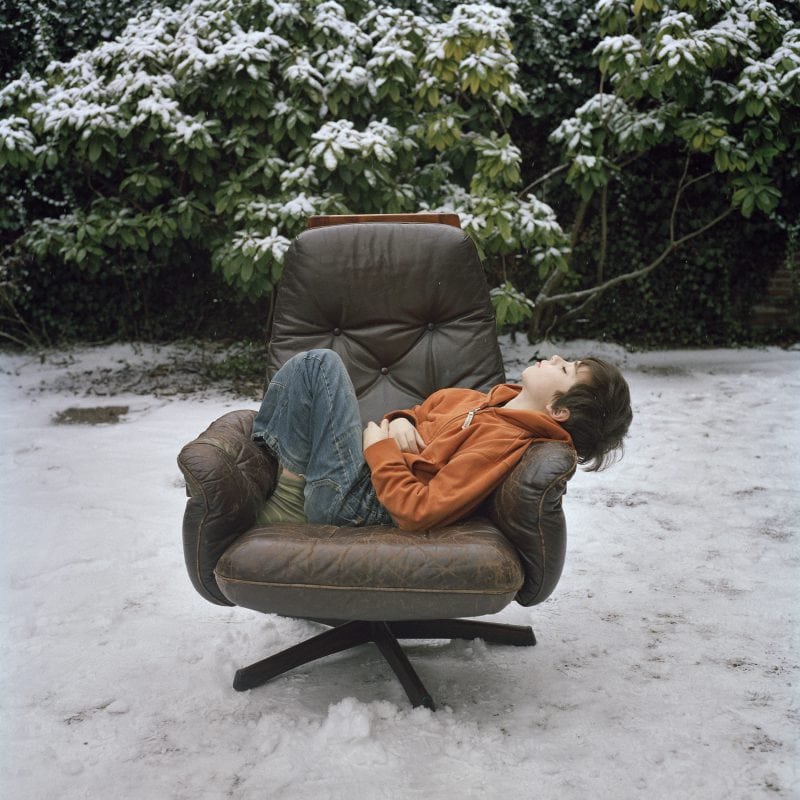

For more than two decades, Sarah Mei Herman has been collecting the subtle choreography of a family in constant transition. Julian & Jonathan, her most personal body of work to date, shows the long arc of her father’s and half-brother’s lives, and across her own position within the subjects. Herman appears and disappears in the images, sometimes a shadow, sometimes a presence just outside the frame, exploring the space between belonging and observing.

In our conversation, Herman reflects on the fragile triangulation at the centre of the book, the emotional and technical challenges of photographing the passage of time, and the way long-term work can transform one’s role as daughter, sister and artist.

Gaia V. Marraffa: Sometimes, in the images, there is almost an unintentional choreography between the three of you, like a fragile, transitional togetherness. Was there a moment when you felt that the camera allowed for more intimacy than there was in everyday life?

Sarah Mei Herman: I’m not sure the camera created more intimacy than we share in everyday life, but it did create a different kind of intimacy; one that was only possible during these photographic sessions. As I write at the end of the book, these were “moments in which we were silently together,” and the camera seemed to invite that silence. Its presence created a space of concentration and attentiveness that doesn’t seem to exist in the flow of daily life.

Photographing my father and half-brother required a certain distance, both emotional and observational. That distance allowed me to look at them, and at our relationships, with a clarity I wouldn’t have otherwise. At the same time, this position was not always easy. I am deeply embedded, yet also an outsider looking in: I have my own family life, and I move in and out of Julian and Jonathan’s world at my own rhythm. That creates a sense of melancholy in the brevity of our encounters, but also a kind of sensitivity. It helps me notice the small shifts and transitions that would be invisible if we were together every day.

So the intimacy the camera allowed was a fragile, transitional togetherness, one shaped by observation, by distance, and by the awareness of our individual positions within this very particular family constellation. The camera didn’t replace real-life intimacy, but it made another layer of it visible.

GM: In the book, you appear almost as a “side” presence, a figure who enters and exits the scene, leaving traces of herself behind. You take on the role of observer while attempting to enter into an emotional system that did not grow up with you. How did the act of photographing a relationship that you were trying to understand as you were building it transform you as a daughter, as a sister, as an artist?

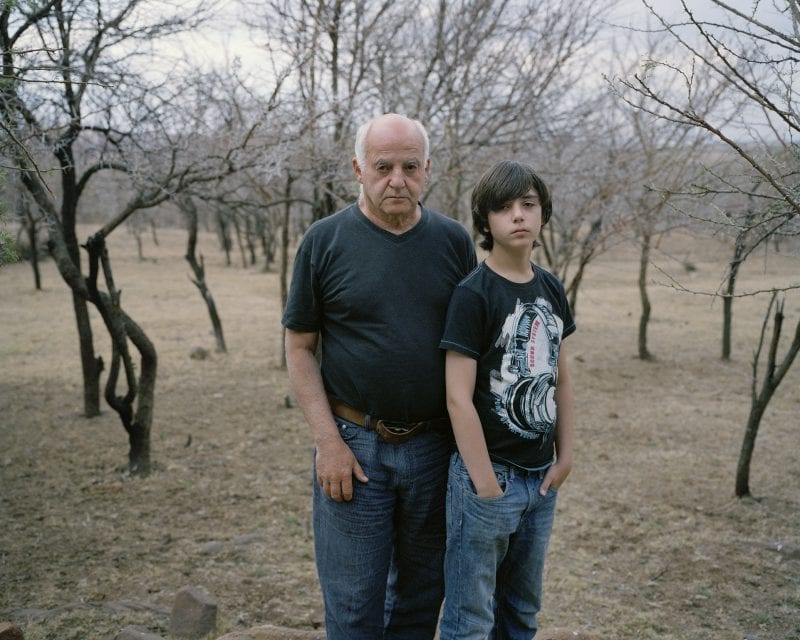

SMH: Working on this project over such a long period, returning to my father and half-brother again and again over two decades, has changed me in all three roles. At first, I approached the work with the sense of an observer stepping into a family dynamic that had grown in my absence. There was always this tension: I am deeply connected to them, yet I also arrive from the outside. This position was sometimes painful, but it also made me attentive in a very particular way.

Photographing them while our relationships were still forming made me aware of the value of continuing, even when it felt complicated and uncertain. I learned that staying with something close to your heart, even when the process is difficult, creates its own form of understanding. Over time, the distance I felt became a tool rather than an obstacle; it allowed me to see small shifts and gestures that would pass unnoticed in everyday life.

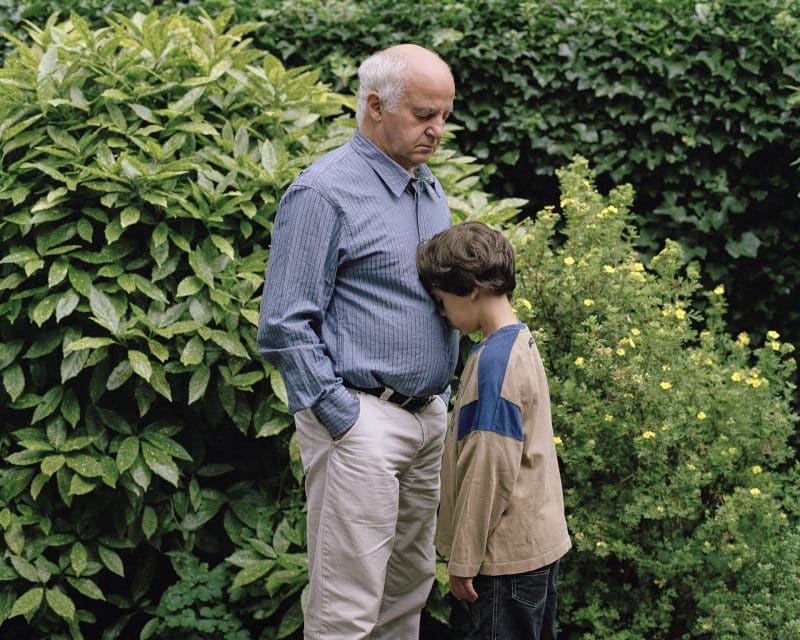

As a sister, especially, something changed. My relationship with Jonathan has not always been easy; there is a natural gap between us, both in age and in experience. But the act of photographing him repeatedly created a bond that exists uniquely within these sessions: a quiet space where we meet each other differently. That fragile bond would not have come into being without the camera.

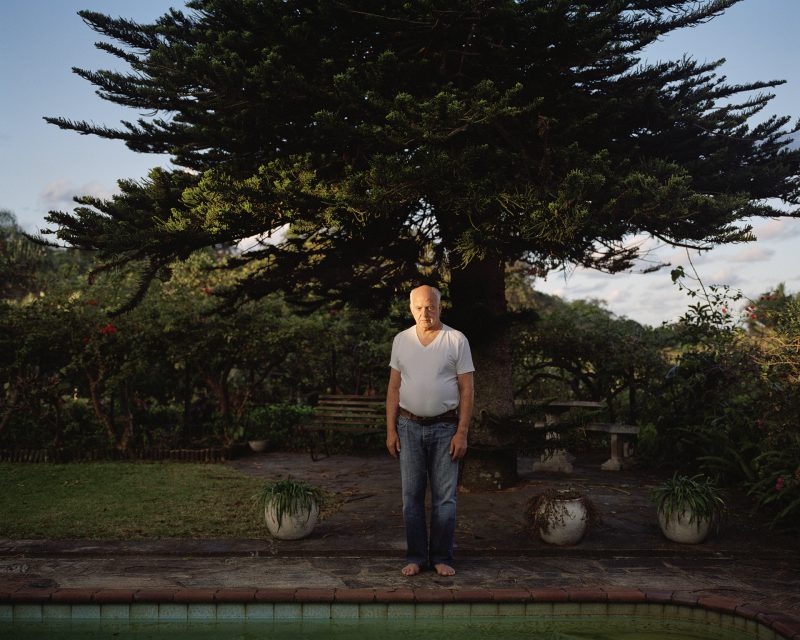

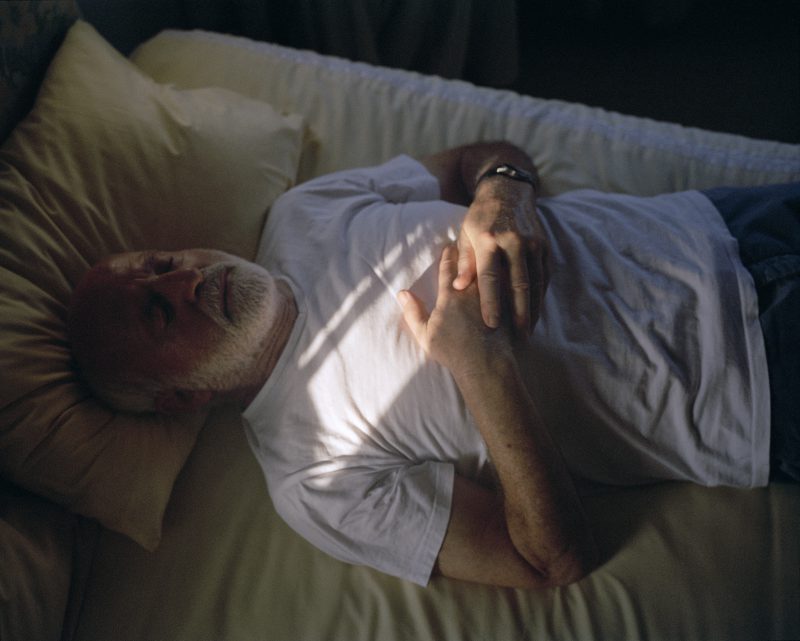

As a daughter, I became more aware of the passage of time, of my father growing older, and of the role reversal that slowly but inevitably begins. And as an artist, I learned to trust the long arc of a project, the slow accumulation of moments, and the power that comes from showing up over and over again.

In the end, the project transformed me by revealing that distance and closeness are not opposites but part of the same movement, constantly shifting and constantly asking to be looked at with care.

GM: The passage of time is a theme visible in the images, both in the camera and in the subjects’ stares and bodies. What were the technical and emotional challenges in documenting the visible and invisible changes that the book wants to convey?

SMH: Emotionally, one of the most difficult aspects was witnessing how the relationships within this small constellation shifted over the years. When Jonathan was young, he and my father were incredibly close; as he grew older, especially around the age of fifteen, he began to distance himself. Observing that change from the position of both daughter and half-sister was tender and sometimes painful. At the same time, it allowed me to register the subtler, invisible transformations, the hesitations, the new boundaries, the quiet ways in which people grow apart or return to each other.

The inevitable passage of time was another emotional challenge. Looking back at the photographs made over so many years, I became aware of how my father was aging, and of how our roles were slowly shifting. The images revealed changes that I did not always register in the moment, confronting me with the finiteness of our encounters and the fragility of what binds us. The photographs became a way to hold those moments still, even as everything kept moving.

Technically, the challenge was continuity: how to keep going over such a long period without repeating myself, how to find new ways of looking, new locations, new forms of light or composition that could reflect the evolution of our relationships. It was not about technique in the strict sense; it was more about staying open, remaining patient, and finding a visual language that allowed those gradual changes to become visible.

In documenting both the visible changes and the quiet shifts that are harder to put into words, I realised that the true work was not only photographic but relational: keeping the connection alive, returning even when it felt difficult, and allowing time itself to become a collaborator in the project. Over the years, this practice taught me that persistence, both personal and artistic, has its own quiet power.