While browsing through the myriad of July 2023 dates of Richie Hawtin, you come across the classic names of clubbing temples that have made the Anglo-Canadian DJ’s reputation so impressive: Ibiza, Mykonos, Manchester… To your surprise, one name pops up among all these giants: Crevoladossola, Italy.

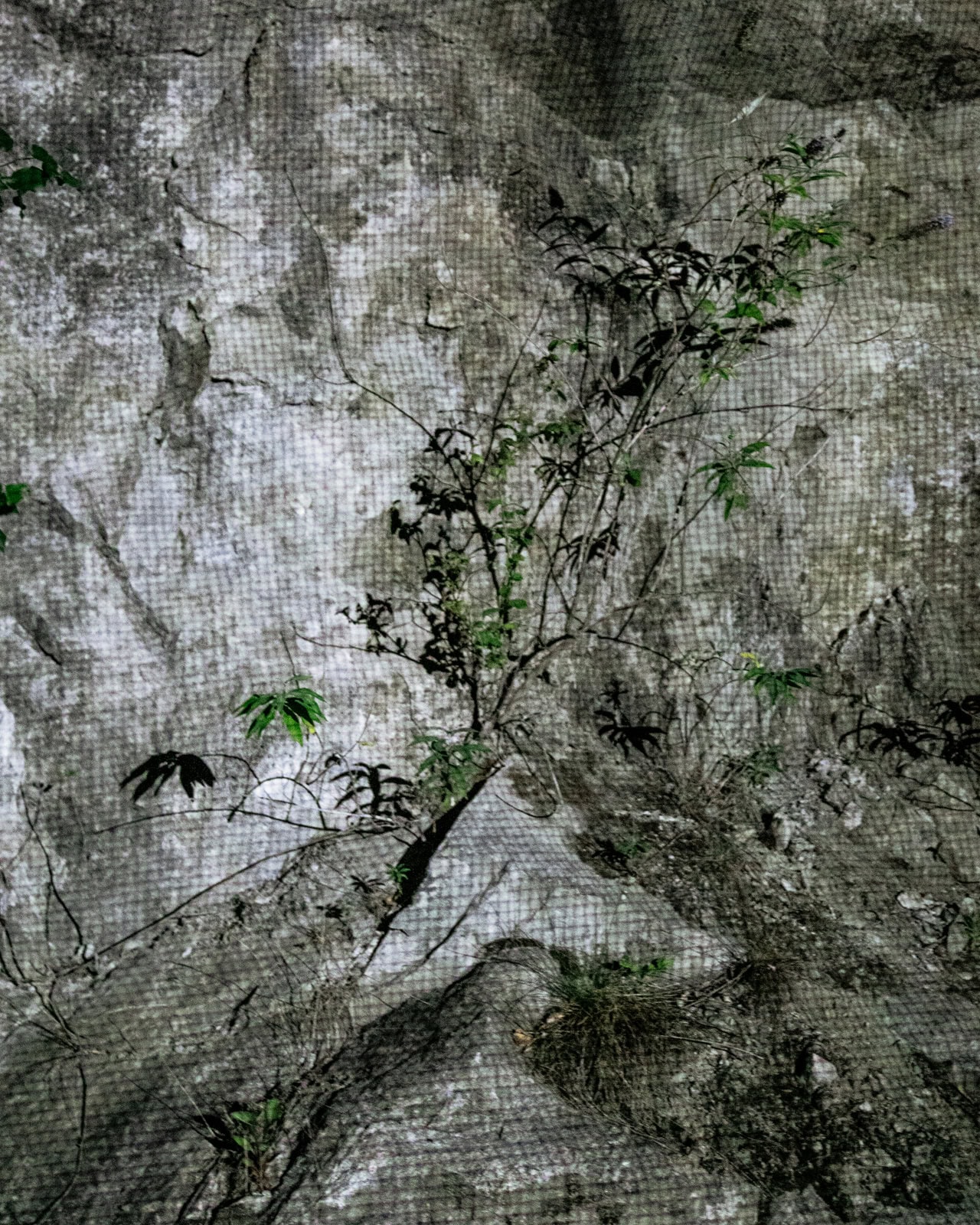

Wikipedia reports a population of 4,511 inhabitants for the small Piedmontese village, but that number increases for that one unique weekend each year when one of Italy’s most evocative events takes place: Nextones. Four days of music, audiovisual arts, and camping in a former stone quarry transformed into a natural theatre thanks to an idea from Threes Productions—the same one known for Terraforma Festival in Milan—and Tones on the Stones.

“In every club where I’ve played, there’s something special that sets it apart, but a place like Nextones is entirely unusual, both for me and the crowd,” Richie tells me in a room at Mandarin Oriental in Milan. His DJ set at the quarry will be tonight, and you can already sense his excitement for this unique date. “This makes me approach the performance differently. I could play the same records as on another night, but the set would be completely different. The art of DJing, for me, means living in the moment with the people. They push you, and you push them, and the location is the key to this exchange.”

As expected from the least 53-year-old man on the planet, the result was a memorable set, with many new records “by young producers, all quite fast in rhythm,” in an almost sci-fi atmosphere. Behind Richie, stunning visuals projected on the bare rock created waterfalls and geometric games while the bass drum beats selected by a monument of electronic music reverberated all around. The acoustics of the place seemed almost carefully designed, rather than shaped by the brutal action of buckets, drills, and dynamite. What better context to play some good techno?

Claudio Biazzetti: So, how did you end up in Crevoladossola?

Richie Hawtin: With the guys from Threes, we started talking five or six years ago about doing a Plastikman show. That project has yet to return, but in the meantime, we still wanted to do something together. I’ve been a DJ for so long that sometimes I feel like a hamster on a wheel. As good as they can be, sometimes the gigs are so numerous and close together that they end up looking all the same. It’s essential for me, perhaps now more than in the last 30 years, to accept dates that can challenge me and put me in front of different places, situations, and audiences.

CB: And why is Plastikman still making us wait?

RH: I’ve always left that project the freedom to emerge when I felt like it. Sometimes it’s not the right time, when I’m doing DJ gigs or involved in other projects. It’s always there, like a small room in the house with a door always open. But sometimes I spend much more time in different rooms, so to speak. Lately, I’ve been thinking about it more often, but it’s also a matter of timing, based on what’s happening in the world and in techno. I think the moment for Plastikman is approaching again, though.

CB: However, there must be some criteria, more tangible than others, to open one of those doors, right?

RH: I like to push myself beyond and do the same with my audience. But club culture is in constant generational turnover. It’s a young movement. So, there are always new people coming in at 18 years old and staying until 28-30, and then often they return to “real life”. In essence, they stop going out. So, you have to catch them at the right moment. When they are already into techno or house but are ready for something different. Because if you come in full force out of nowhere with an artistic project like Plastikman, they might not get it. You have to be ready to be pushed. In the last two years, especially after Covid, there has been a massive explosion of hard techno, fast techno. It’s an extremely exciting moment, especially for the younger ones but, still using the metaphor of the house, many of these people are still on the doorstep, not fully inside yet. People are curious at the right level for Plastikman to come back. All the necessary premises just need to come together. Thanks to this widespread curiosity, in the last two years, I’ve been touring a lot as a DJ. Just to say, “Hello, everyone, welcome!”

CB: “I am the homeowner!”

RH: Exactly! “You’ve never been in here, but this house has been here for at least 30 years. Now, we’re also opening the back door, okay?”

CB: Have you ever felt the need to adapt to the new generations?

RH: Honestly, I think being a DJ somehow also means keeping up with the times. Throughout my career, I’ve been known for my techno, for its minimalist nature. But if you look closer, depending on the period, it might be more house or more pop, catchier and melodic. At one point during the two 2010 collections, I had become too melodic, so I changed course. Adapting also means asking yourself: who am I? What is my message, and how can I deliver it to people? But the message has to be clear, well framed. I think the art of DJing successfully is understanding that there are 50% of your fans who will always follow you, but there’s another part that comes in, stays a couple of years, and just wants you to give them the best fucking moment of their life.

CB: You have unsuspected fans everywhere, but did you know you also had them in the Norwegian black metal scene?

RH: No! I didn’t know that!

CB: Fenriz of Darkthrone has the Plastikman logo tattooed on his forearm.

RH: No way! Then maybe that’s the right direction that Plastikman should take. But, you know what? Plastikman, at its full splendour, is hypnotic—trippy music. That feeling that takes you elsewhere goes beyond techno or house. It’s a headspace that doesn’t always work at festivals or clubs because it’s not easy to instil it in people at a specific moment. They have to be ready, and I have to be ready too. Because sometimes, I’m not in that headspace. Sometimes I’m just happy to enter a club and play some fucking records and have fun. That’s it.

CB: One of Plastikman’s most famous anthems is “Spastik,” a simple drum loop that repeats endlessly. What do you think is the secret of its success?

RH: Certainly, the times in which it was released helped. It was 1994. After that, it has everything you look for in a dance track. It’s intense and straight to the point. There’s nothing superfluous. Its purity is its power. But I wonder if it’s just a matter of timing. I recently played it for people who had never heard it, and they immediately appreciated it, even though we’re not in ’93 anymore. I believe that, in the end, everyone loves to dance, to move. Whatever the genre of music. Even people who don’t go to clubs. Everyone has an internal rhythm, and that track is entirely rhythmic; it’s very basic. There’s me, a human being, and a drum machine. And even if you know nothing about music, I think people can tell when something is happening live. Whether there’s a guitar or not, I think you can feel if there’s passion in a piece. Sometimes, while I’m playing the drum machines in the studio, I think, “Okay, this is good,” and then I record it. Sometimes, you forget to record, and everything is lost. Fortunately, I recorded “Spastik”. I believe it was November ’93 or ’92. It was a very intense and passionate time for me and electronic music. I was starting to have success and travel. I was a kid in the studio but touching the world. You can feel that emotion in the track.

CB: What is your relationship with synths? Do you spend hours searching for the perfect sound, or are you already so experienced that you find the right combination immediately?

RH: I think it’s all a matter of taste and intuition. You do it in the easiest way possible: sometimes in a simplistic way, sometimes with more effort. Some people are very good at what I call the art of noodling, sound design. And this is reflected in a certain type of music. But I don’t think that’s my case. Mine is finding a structure, perhaps noodling for a couple of days or weeks at the beginning, and then, once I find what I like, I start recording tracks one after the other. And we’ll see what happens. Usually, one or two weeks later, a new album is ready. Sound design is not fun for me; I prefer putting everything together. If the search for a sound becomes too intellectual and cerebral, then something is wrong. My presence in the studio is like a continuous live show.

CB: Before going on stage, do you always feel the same sensation as before?

RH: Yes, I’m always nervous before going on stage. It’s difficult to describe. It’s not that if there are more people, I’m more nervous or I prepare more. It’s different every time. Sometimes you go on stage in a very small place, and you think, “What the hell am I going to do now?” And people are right there in front of you. Or you go on the big stage and start playing like crazy. Whether it’s a DJ set or a live set, for me, it’s a matter of being “relatively prepared,” as I call it. I don’t like everything to be planned out. It’s not like I go on stage and feel confident: I just need to know a few basic things. Where is my computer, what kind of mixer it is, maybe a couple of tracks. And then, press start and improvise. Not knowing exactly what I’ll do and what will happen and thinking, “Okay, I must not fuck up now, and if I do fuck up, pretend you didn’t fuck up.” This feeling is the best thing for what I do. Some people have everything prepared, like all the tracks in a setlist. It works for some, but that would drive me fucking crazy. From the start, you feel alive when you’re onstage.

CB: Yes, I think at some point, you can perceive if the person you’re listening to has a prepared tracklist.

RH: Yes, literally. Because everything is too perfect. One of the criticisms I have about dance music nowadays, which is very present among new DJs and the public, is that the energy level is very high. One bomb after another. In my opinion, there’s a need for moments of atmosphere change, or even moments when you make mistakes, and from there, you take unexpected directions for yourself first and foremost. That kind of storytelling, in my opinion, is beautiful because that’s what people remember. Especially now, anyone can go on stage and play devastating tracks with two CDJs, and the audience raises their hands when you raise yours. It’s not rocket science. I tend to go beyond this.

CB: After all these years, do you still perceive the mystery in electronic music?

RH: Yes and no. To go back to my somewhat cheeky comment that everyone can be a DJ now, I’ve always wanted to welcome as many people as possible into electronic music. I’ve always wanted to be as transparent as possible about how I sound. It’s great to have so many people involved. But when there’s a tendency to follow the herd and be cookie-cutter, then the beauty of the mystery disappears. If everyone thinks they can get on stage and do exactly what the artist is doing, who are you aspiring to be? When I was a kid and watched Prince on TV, I thought, “Damn, I’ll never be Prince!” Who would ever think that? But you can think of being like someone, someone who gives you the aspirational energy to become who you are. Because it’s nearly unreachable. That’s the sense of mystery, of magic. If everyone plays the same records, the same drops at the same time, sometimes you’re like, “I could have done that.” If too many people think that, then the mystery disappears. Our scene is huge now, but it could change radically if it becomes too conventional.

CB: You’ve been recognized with many awards and honours. However, we agree that the title of Sake Samurai is the most incredible one, right?

RH: Sounds pretty cool, right? I remember when I received that title. I had to go to a famous, sacred, prestigious temple in Kyoto and go through this two-hour ceremony. Part of this ceremony was public, and that was simple. But inside the temple, where only a few people on rare occasions can enter, we were sitting, and time stopped. Someone pressed the freeze button on time. It was something beautifully serene and magical, surreal. For a second, I remember thinking about how crazy and incredible, absurd, and beautiful it was for me, a DJ, to be in that temple receiving this honour. Because there’s nothing else like it: it’s a tradition that gets lost in the centuries of Japanese tradition.

CB: Where does this passion for Sake come from?

RH: I really like it, and I was also studying to become a Sake sommelier, even though I knew I didn’t want to change my profession. It’s just that when you travel around the world, you encounter things and people that resonate with you. Sometimes they resonate so much that you want to deviate and spend more time learning about them. And Sake was exactly that. In the first approach, it tasted great; it made me feel good, with a hypnotic, warm and fuzzy effect. As I got closer, I became more interested; I met some brewers, and I learned new aspects of Japanese culture. But I couldn’t tell you the exact moment when this love was born.

CB: No?

RH: Wait. Yes, I can tell you exactly when it was born. It was in Japan, around 2005. I was in Hokkaido, which is an island in the north. We were in a traditional inn with hot boiling springs outside. During the night, we sneaked out into the hot springs. It was all very un-Japanese because we were both boys and girls, and we had Sake in hand. We got drunk drinking Sake in hot water, surrounded by mountains and the midnight moon illuminating the snow. And my friends were like, “Okay, if you like Sake so much, you should do something about it.” So I decided to open a Sake Bar in Berlin.

CB: And then you did it.

RH: It took more than 15 years to accomplish the mission, but that was when I decided to turn words into action. Professionally, I started drinking Sake in 2007. At that time, I already had about 17 years of professional DJ career. I go through periods where I love what I do, and others when I need something else. At that point, Sake gave me something new to study: get to know new people, take a little break from the scene and see it from another perspective. In the Sake community, I found a world of truly passionate people, just like the one from which I was taking a little break. And this thing is as if it reignited the passion for both.

CB: Among all the things you do, DJing is still the one that takes up most of your time, right?

RH: Yes, it’s still my main activity. I can see it in two ways: it’s my job, meaning the one that earns me a profit, which often helps me finance all my other crazy projects. And then, it’s also the way I can be most easily creative. Because as you become an adult, responsibilities increase. I have a family, a daughter, and I can’t always go to the studio. Sometimes, when you have a creative urge but can’t go to the studio, it can be a little frustrating. However, when I’m on tour, as I mentioned earlier, all I need is my two or three things on stage to fully unleash my creativity.