Questions On is the video interview format created by C41. It consists of three simple questions addressed to our network of friends, partners and creative minds.

This series will go through Printed Narratives, questioning the role of contemporary publishing in the digital era. This episode features Alecio Ferrari, an Italian photographer and visual researcher that lives and works between Rotterdam and Milan. He achieved a bachelor’s degree in Graphic Design & Art Direction at Falmouth University in Falmouth (UK) in 2018. His portfolio is a mixture of fervent aesthetics and narrative, developed from a wide experience in visual arts and the creation of both reportage and personal works with narrative at their core. With a skill set ranging from editorial design, visual communication and photography, he developed the ability to communicate through images in a genuine yet efficient way.

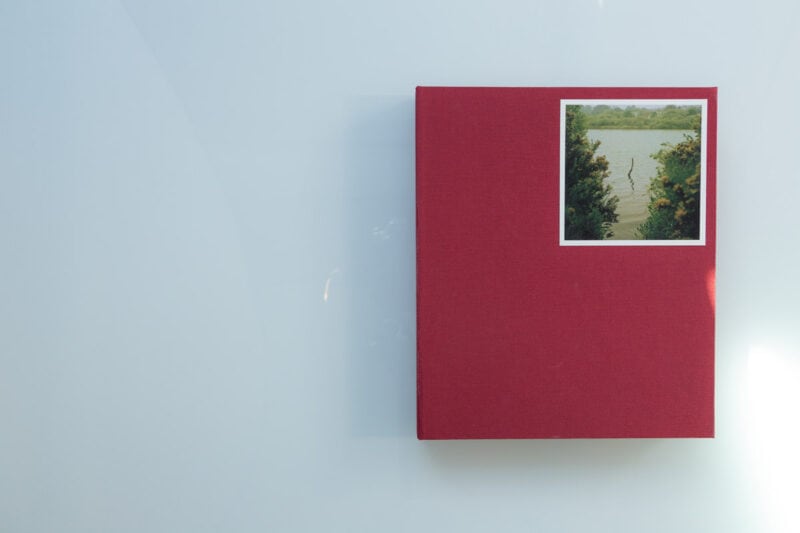

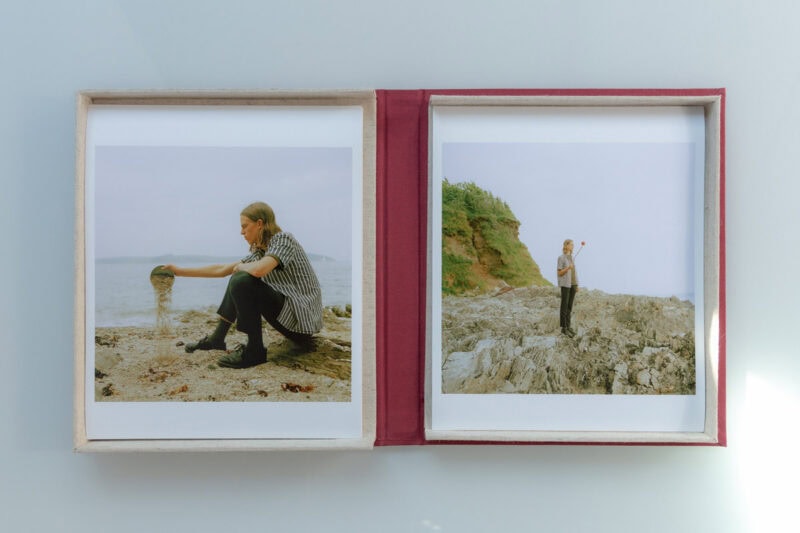

Lonely Boys is a photographic series realized by Alecio Ferrari between 2017 and 2018 in Cornwall, UK. The body of work is developed as a fictional narration, a series of both portraits and landscapes of six boys, alone in their own environment.

More about Lonely Boys – words by Veronica Poggi:

«In the months of March to May 2018, I wanted to become closer to the Other Castaways, to get to know them better.

The weather was improving, it was still pretty cold but gloves were no longer essential. It was becoming easier to hang out together outside. The beach was the perfect spot to meet up with the boys, we often went there as we knew it was important to never lose sight of the horizon. We didn’t speak that much, and we had to sit quite close to prevent the wind from drowning out our voices. The wind constantly blows, so much so that all the belongings I arrived with gradually flew away across the beach. The land, it changes quite significantly from one stretch to the next. No two places share the same climate, and no one person experiences the same climate for too long.

There is an abundance of tropical plants. As I made my way to see the first of the Other Castaways, I found myself crossing some sort of subtropical forest. The route was dark and gloomy from the vegetation, and only a few of the photos I took there are actually visible. The photography equipment I used was part of my own survival strategy.

The Castaway’s equipment belongs to each boy’s past: the objects came here with their owners and we assign to our object a unique purpose. We make the most of our equipment to survive alone on this land. My equipment, in the past, had a different purpose: it was the perfect pretext to approach people. Here there is nobody to approach, nobody to take pictures of, I am alone for the first time.

I have collected 3587 pictures of plants. I’m starting to get bored.

I am going to take my equipment and I’m going to look for the boys.»

What remains to be done after a shipwreck? Why is it important not to lose sight of the horizon?

I believe that after a shipwreck the survivers need to find a new direction, which is not specifically a destination but a path. You definitely got to work harder than before to stay afloat, but then, at the same time, try to take the chance to rebuild something, to invest and believe more in your passions and talents, and to dare as well. The photographic series I am presenting right now is called Lonely Boys and it’s a sort of anticipation of current times, which is interesting and harsh at the same time. It has been shot in 2017, while I was living in the South West of England, and actually the pandemic was just a remote and forgotten word. The storyline is developed as a sort of fictional narration: there are six boys, which represent six survivors that, after a shipwreck, found themselves on a desert island, and they strive to find a way to stay alive. The selection of shots is a mix of portraits of these six survivors and landscapes of the places where they landed. While I was reflecting on the sense of the project, which it has been shot and also written three years ago, I just realised how much contemporary the topic was – definitely more contemporary than the time it has been shot. So this is actually the main reason why I decided to go back to the series, re-edit the selection, try to arrange them better together, print them and publish the body of work.

Today we are all somehow castaways on a desert island. What is the «unique purpose» of your equipment? Do you prefer shooting 3587 pictures of plants or are you still looking for people?

It is really curious however to define your own equipment and try to make a living out of it. The equipment can be a tool, a musical instrument, a machine, or even a skill or competence. It’s funny how, as soon as you find this sort of baggage, which is this tool, you start to bring it along with you all of your life. I’m really fascinated by the relation between human beings and these objects, and how much we feel close and addicted to them. Personally speaking, my sort of revelation or enlightenment raised me when I realised that all I needed to live with was a photo camera and my eyes (literally: just a camera and my ability to see). It was a sort of enlightenment because as a kid I was pretty hectic, and not really the best student; it was really hard to concentrate for me, I was very inattentive, and before university, I was really struggling to find a sort of position in the world. In this sense, the act of photographing just gave me the chance to really concentrate on something, to focus on one thing and then try to perform that. I then started to invest my time training my eyes to select tiny pieces of reality, to see a sort of beauty around me, and create a sense out of it. I really remember when, the first years I was starting to take pictures (I was like 15-16 years old), I was continuously filling my days watching starring, analysing images of other people – images that I love – and try to understand which was the technique, the situation and the method used. I really think that during those years I created my own view of reality, and also my own taste. From that moment almost, from the moment I started to be really intrigued by images, photography became a real obsession. You become ravenous of images, you wanna see more of them, you wanna discover how those images were created and you spend so many hours looking at it: looking at the light, looking at the composition, trying to understand the secret of perfection of that specific image, and then you wanna make that image yourself. So then you start to realise how the work of the photographers, or of the images makers, is really close to the work of an artist… We’re making things from a scratch. We’re not making physical objects, we’re making printed sheets of paper or sometimes – most of the times – digital files, but in that single frame, in that digital file, there is so much. There is so much research: there is so much desire.

Publishing could be seen as an anachronistic practice. Why do you think it could still have a role in shaping contemporary visual culture? Is printing a way to return images to where they belong?

The publishing practice may have something anachronistic 10-15 years ago, when everyone was saying «the print is dead», but that was just a false alarm I guess. Digital technology entered as a new player into the publishing system, replacing several uses of the paper, such as documents, contracts and newspapers, but then opening infinitive possibilities to new forms of communication, which is extremely exciting. Nowadays, there are many ways to spread images and visual culture around, but the printed matter has managed to maintain solid integrity through the years – and through decades and centuries. Firstly because books are solid objects that resist the test of time. Books are kind of affordable if compared to the past, and also the action of leafing through the pages of books is a very enjoyable and sensual process as well. Another aspect to consider is there are limited struggles between print and digital, which were very common during the previous years, but now this conversation is almost gone, almost disappeared… There are less and less conversations about which is the best, print or digital. There is no fight anymore, rather there are new researches, methodologies and challenges. I think that the real goal right now is how to use these two mediums together in the most efficient way – how to merge them together, how to make the most out of the integrity of the book and the fluidity of the digital landscape. Photography projects are not only printed books anymore, and so printed books might exist on paper on one side, and then transferred online as a series of images with sounds: as videos. For instance, the Dutch photographer Rob Honstra, a documentaries photographer, has a website that is really interesting and exciting. It’s not just a library of his works, but it’s a sort of virtual experience. It’s a mix of documents, sounds, videos and images, really working together as a whole.

Credits:

Featuring: Alecio Ferrari

Curated by Robin Sara Stauder

Editor: Alice De Santis

Visual: C41.eu