At the foot of Mount Vesuvius — where Ranieri has turned volcanic stone into a true design language — Paisaje de Reflejos takes shape: a site-specific installation conceived by Mexican architect Diego R. Borrell, founder of the experimental studio TANAT, during a creative residency at the company’s Terzigno factory in July 2025. The work will debut at Castel Sant’Elmo from October 10 to 12, as part of EDIT Napoli 2025 and the EDIT CULT program, curated by BY, Galería de Arquitectura (Francesca Borgonovo, Luis Young). It represents the first chapter of a project that will continue in Mexico City in 2026, establishing a transatlantic dialogue around volcanic stone as both shared heritage and narrative medium.

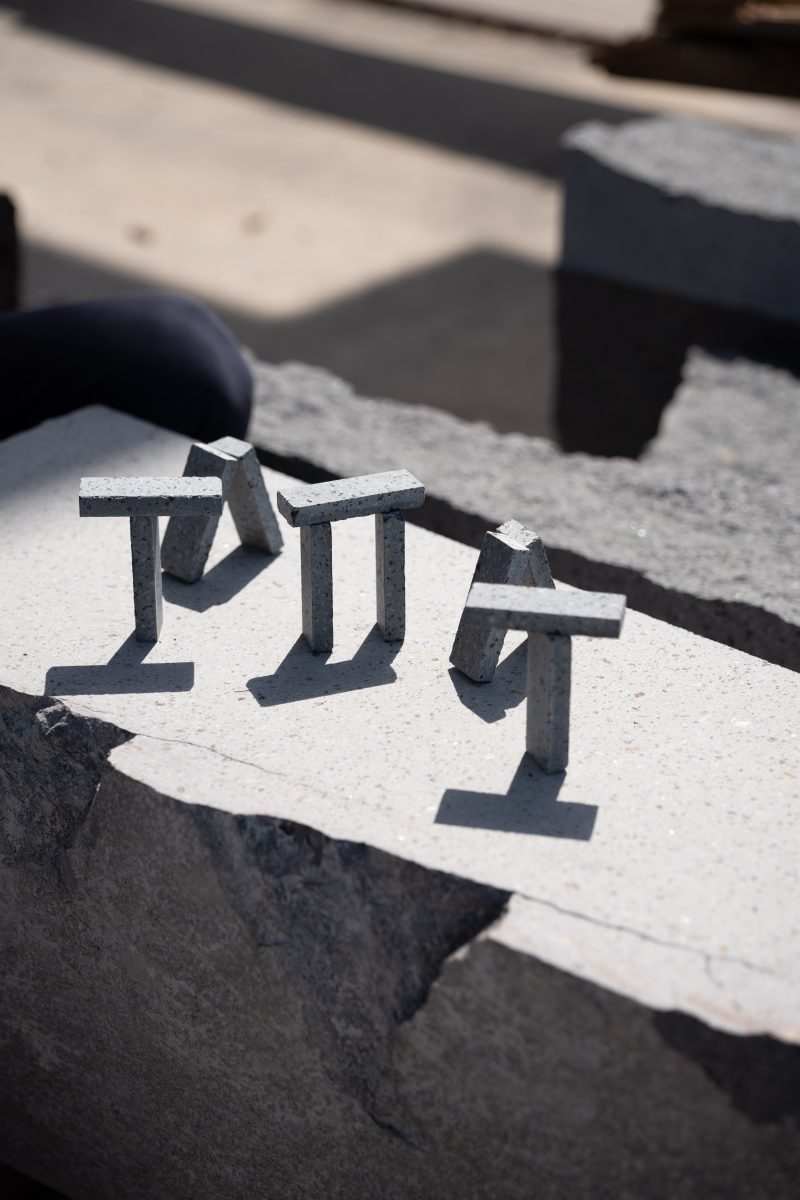

Conceived as a compendium of the Neapolitan landscape, the installation reinterprets three symbolic elements — the volcano, the city, and the gulf — through a dramatic composition of three totemic towers in volcanic stone emerging from a dark, almost magmatic floor. Inside, micro-architectures in glazed lava evoke fragments of the Neapolitan urban fabric, while the rough stone blocks at the base transform upward into sculpted and refined forms, tracing a stratigraphy of geological and architectural references. For Borrell, architecture is an “archaeology of identity,” a space of memory built through light, shadow, and matter, because, as he affirms, “cities are fictions… places sustained by the immaterial substance of human experiences.”

The project stems from the affinities between Naples and Mexico City, two distant cities united by their ancestral relationship with volcanic stone — a material that shapes landscapes and preserves memory. Within this dialogue, TANAT brings to Italy its ongoing research into the relationships between architecture, territory, and culture, previously explored in projects such as Cronoboros (Museo Experimental El Eco), Escribir un Paisaje (LIGA), and El Retorno del Agua (Casa de México en España).

For Ranieri, a brand born at the foot of Vesuvius and led by Giovanni Ranieri, Paisaje de Reflejos marks a new chapter in a journey that merges craftsmanship, research, and experimentation. Volcanic stone — transformed into surfaces, furnishings, and artworks — becomes a symbol of ongoing metamorphosis between destruction and creation. “The collaboration with Diego Rivero Borrell allowed us to activate a deep dialogue between two territories that are distant yet surprisingly akin…” says Giovanni Ranieri, emphasizing how the contrast between cultural languages can generate authentic synergy and new expressive forms.

At Castel Sant’Elmo, one of the venues of the National Museums Complex of the Vomero and a key stop on the EDIT CULT 2025 itinerary, Paisaje de Reflejos presents itself as a compressed landscape and an atlas of reflections: a device interweaving architecture, memory, and design culture, destined to evolve in 2026 with a new exhibition chapter in Mexico.

On the occasion of the Neapolitan presentation, we met Diego R. Borrell, founder of TANAT, to explore the dialogue between matter and memory, the relationship between Naples and Mexico City, and his vision of architecture as an “archaeology of identity.”

Ritamorena Zotti: How did TANAT begin, and what was the studio’s original concept?

Diego R. Borrell: Tanat was born in 2019 as a studio interested in the constant dialogue between architecture, art, and research. The continual leap between these three axes allows us to both formulate new questions and build new provocations. Art enables architecture to expand in scale, narrative formats, and exhibition media. Research, ultimately, is what guides us in the ongoing search for the resonances that our own time constantly brings.

RZ: Regarding the connection between Naples and Mexico City, what specific event or experience made you sense a link between these two volcanic cities? How did this translate into the EDIT project?

DB: I think it was when I realized that to fully uncover the city of Pompeii, one had to remove 14 meters of volcanic ash. That was when the connection with Mexico City struck me in every way. Perhaps it’s difficult to describe fully, but in short, Naples and Mexico City share a stratigraphy—both historical and geological. Historically, they are cities in constant tension with the landscape. Sometimes, human force transforms it, but other times, the landscape covers it once again. Layer by layer, a historical narrative takes shape, filled with dissolved memories, nostalgic presents, and always uncertain futures.

RZ: Can you describe your installation at Castel Sant’Elmo, and which decisions were influenced by the landscape, wind, elevation, or the Gulf’s light?

DB: Well, Castel Sant’Elmo is both a fortress and lookout. It was built at the highest point of the city for one reason only: so that the gaze could reach as far as possible into the landscape. In a way, Sant’Elmo is an observatory. And although it fulfilled its role in its historical moment, its essential function remains today. From Sant’Elmo, we can observe so much of Naples—the city, the volcano, the sea, and its islands. In previous works, I’ve reflected a great deal on the landscape, a concept as elusive as it is constitutive of our reality. Reflecting on Naples through the lens of its own landscape allowed me to layer, both physically and symbolically, a small personal reflection that, at the same time, seeks to mirror the city in new ways.

RZ: For the towers exhibited at EDIT, what experience did you want visitors to have—rhythm, scale, or pause?

DB: I only wish for something, deep within, to resonate.

RZ: The apertures with micro-architectures in glazed lava—what aspects of Neapolitan urban life are you referencing?

DB: If we abstract the city into geometric forms and spaces, we can recognize Naples’s formal richness—Baroque, medieval, or Roman architectures, often preserved in churches, palaces, fortresses, or ancient temples. Yet the city also has neighborhoods, streets, balconies, altars, arcades, and underground spaces that, along with the sea, its islands, and the ever-present volcano, begin to compose the idea of the Neapolitan landscape. In the end, if we understand the city as a kind of fiction, what we see are reflections of humans thinking and working in the construction of ideas—from a castle to the most everyday objects. In this way, I understand Landscape of Reflections more as a small fictional essay than as a concrete answer to a diffuse reality.

RZ: Looking toward CDMX 2026, what will you change, and what will you preserve to keep the dialogue with Naples alive?

DB: Art can be created out of new provocations and conversations. The proposal for 2026 in Mexico City begins by inviting people to observe, and then to find those dialogues that take us out of the everyday and open new doors of thought. Speaking about volcanoes, about layers, about cities and their meanings—these are themes that, reflected between Naples and Mexico City, can bring beautiful perspectives on the (personal and collective) meaning of landscape.