Perhaps the time has come to be free of certain assumptions that cling to the world of design. From the extremely overused those who can do, those who can’t teach to the even more worn-out form follows function. A series of modern and post-modern assumptions that took hold in an era when the definition of boundaries and skills was necessary yet today, in a scenario involving increasingly complex design themes and applications, have never sounded so sterile. It is increasingly common, in fact, for the boundaries between design disciplines to blur and then blur some more: for design to overlap with experimentation, for teaching to blend into practical application and for form to be the result of a far more complex process than a simple final finish.

It is within this framework that we can examine the work of American architecture studio Outpost Office, based in Columbus (Ohio) and founded by Ashley Bigham and Erik Hermann, two teachers and researchers at The Ohio State University who combine research with design.

The studio was listed among the Next Progressives by Architect Magazine, awarded the Best of Design Award by The Architect’s Newspaper, and the Faculty Design Award from the ACSA – As- sociation of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. Its work has been featured in Log, Metropolis, Mark, Surface, and Avery Shorts, among others. Other works have been exhibited at the Chicago Architecture Biennial, Milwaukee Art Museum, Tallinn Architecture Biennale, Roca London Gallery, Yale School of Architecture, Princeton School of Architecture, Harvard GSD, and The Cooper Union.

The studio’s work is characterised by the use of digital not merely as a design language but as a format, incorporating its potential within a method; humans define the initial variables and software then gives shape to the variants, meaning an exponential number of declinations. This brings us to a complementarity between subjects and tools, in which each is exploited for its specific characteristics and utilised to its best potential. This type of approach requires time, energy and the possibility of error; elements which are often lacking in the classic client-designer dynamic.

What happens then when the person designing is simultaneously engaged in research and experimentation with the limits of their own discipline? And how can you redesign the classic client-design studio dynamic? What animates and influences the work of a designer, independently from the discipline within which they operate, is the relationship of strength and balance between the parties, among other things. A dialogue that follows an evolutionary journey marked by the various steps in the design process, from the brief to the concept, from development to creation. Everything follows a flow, for the most part regular and one-directional, in which the starting point is decided arbitrarily by the client. This classic paradigm is subverted when the design impulse comes from the designer themselves or from somebody whose end goal is not to meet a direct or subjective demand. This alters the approach, the freedom of movement, the rhythm and the tools; everything is focused on the theme to be investigated and the limits to be overcome. The work of Outpost Office very much belongs to this second scenario. At a time in history in which technology is a crucial factor in architectural design, the US studio has decided not to use it superficially as a simple tool for translating languages but as an actual creative tool, in the broadest sense of the term. Far too often, digital is used purely as an alternative language to the “handmade”, a way of regulating and normalising a process, a sort of prosthesis in place of a gesture.

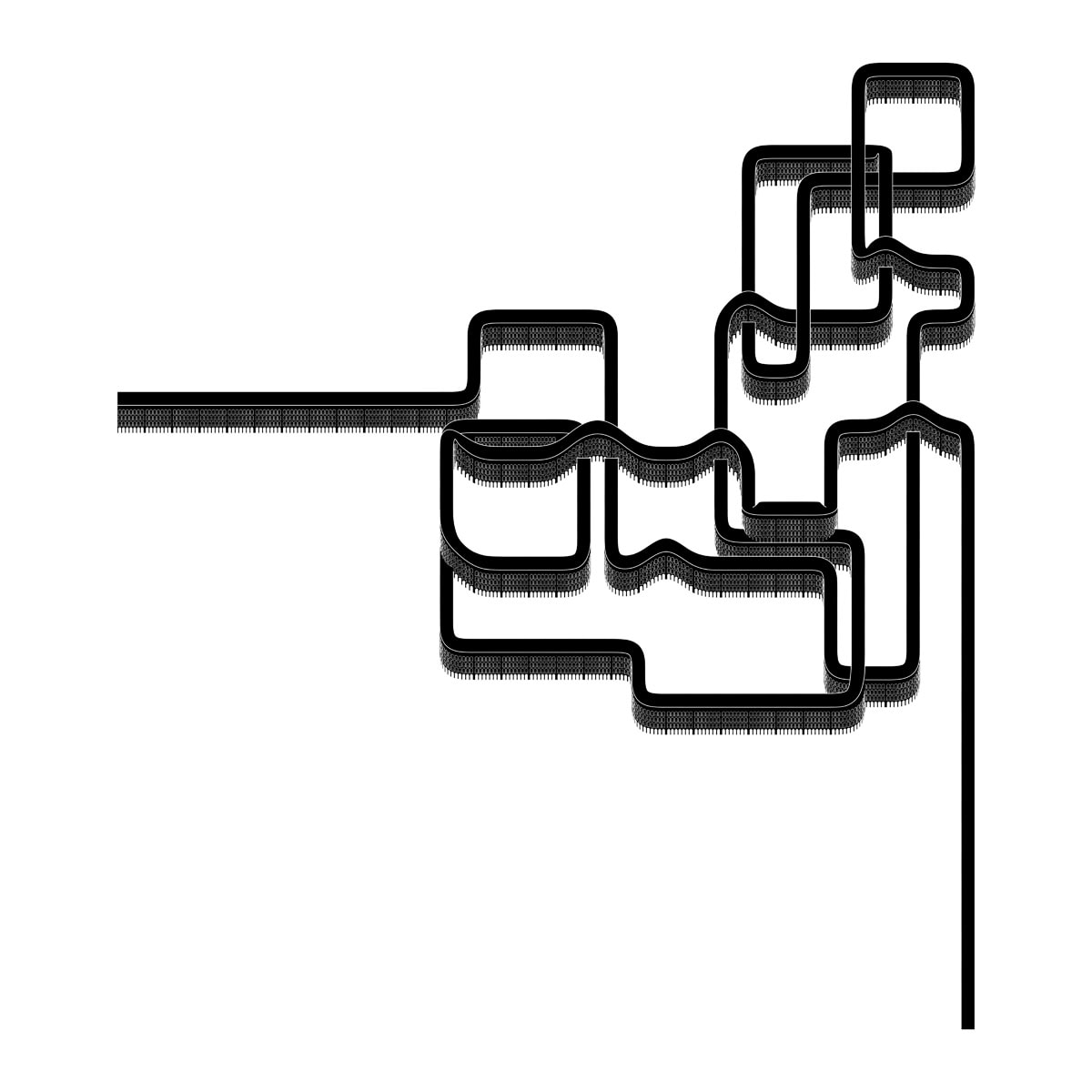

The results of this approach, while stunning and potentially infinite, do not really use the tool to its full potential. There is a substantial difference in what distinguishes a prosthesis from a machine: a prosthesis simply replaces a human function, resolving an imperfection, malfunction or lack of something whereas a machine amplifies potential. Ashley and Eric tackle the discipline by seeking to expand the design limits they would naturally come up against without the use of hardware and software. This is how projects such as Primitive Villa and Long House came about, proposal design formats for collective housing in which the continuity of the accommodation “unrolls”, according to pre-set parameters, within space in the urban and extra-urban fabric as it becomes available. An example of parametric design in which the almost infinite final configurations wouldn’t be possible without digital computing power; humans define the initial variables and design parameters, the machine processes and returns a different result each time. This design approach breaks down the linear process mentioned earlier: need > design solution > realisation. Parametric design in the field of architecture allows you to generate formats that can be subsequently applied on the basis of the construction location.

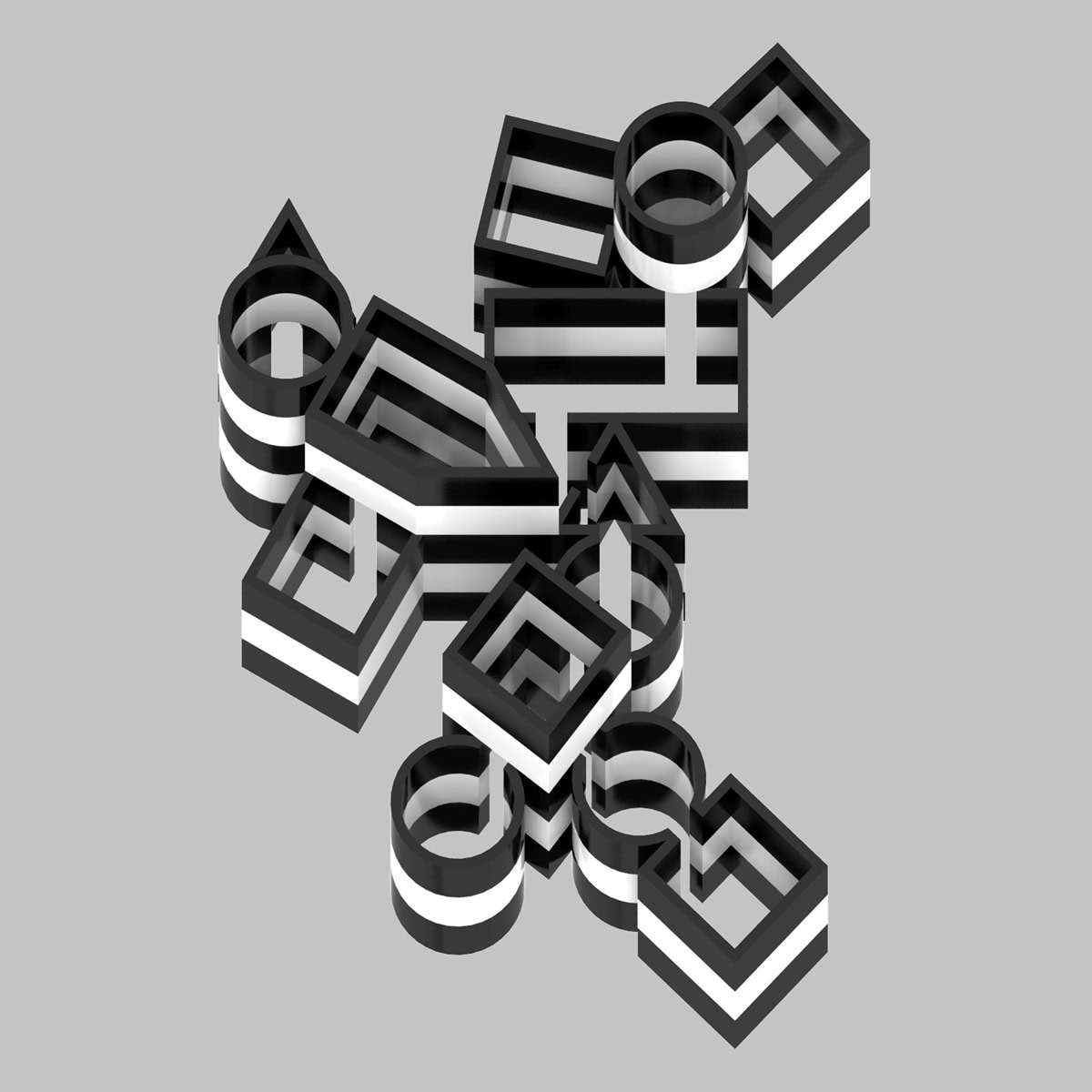

Three-dimensional freedom of movement is experimented with the Computerarchitektur project in which digital design is provocatively pushed to the extreme limit of articulation, generating labyrinthine structures, an architectural typology halfway between space and logic. The two-dimensional archetype of the labyrinth is therefore subverted thanks to the freedom of movement permitted in three dimensions by digital, a freedom of movement that once again does not stop at the surface with simple “façade” virtuosity but lies in the articulation of the structure itself, generating architectures that are impossible to construct and use, the ultimate goal of which is once again to explore the design tool.

From The Ideal City to the futurist architecture of Sant’Elia and the logical/visual experiments of Escher, imagination of the possible and ideal is a recurring theme in three-dimensional design. What Outpost Office does, in this case, is quite simply to truly operate in three dimensions, not satisfied with mere experiments in representation. A subsequent application level is once again made possible thanks to hardware’s capacity for elaboration and calculation.

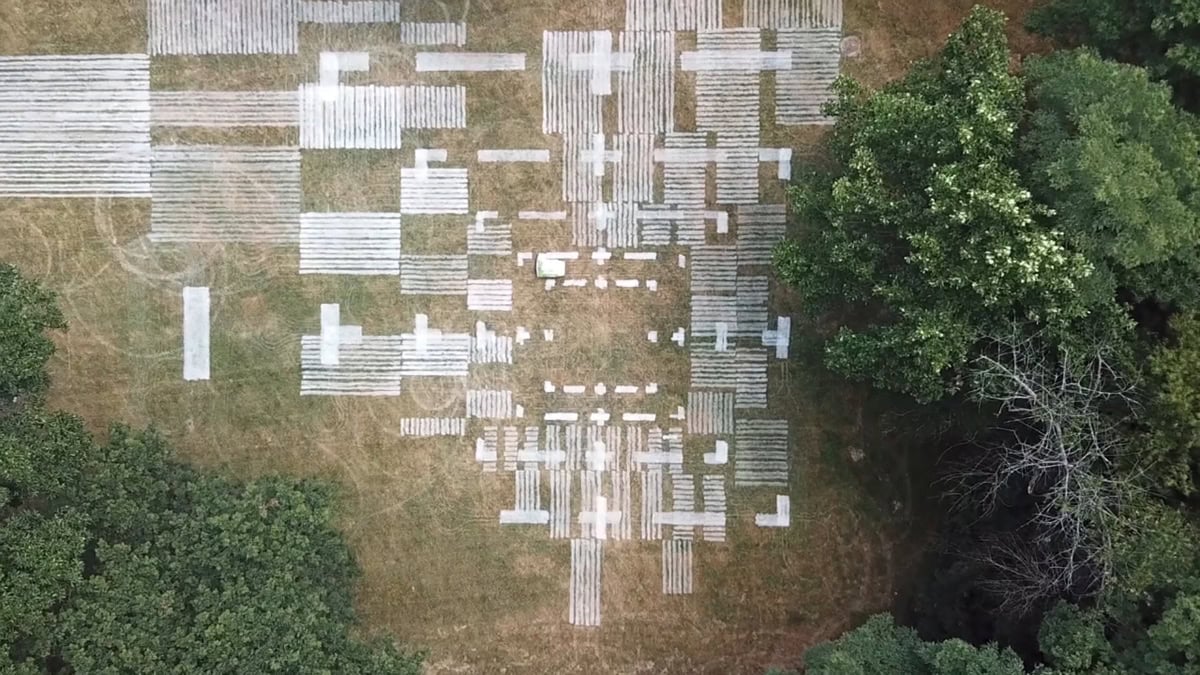

Among the studio’s most recent projects are Drawing Fields and Cover the Grid, both of which investigate the potential of creating land designs using robots controlled with GPS technology. While in Drawing Fields, this experimentation limits itself to 1:1 scale patterns, paths and graphic designs on a university campus lawn, in Cover the Grid, experimentation becomes real design. Remote-controlled robots paint colours on the ground to create outdoor sports fields and public spaces, giving a function to unused surfaces in the western suburbs of Chicago. This sees the application on an urban scale of experiments carried out on a small scale, bringing research born and developed within didactic confines to maximum fruition.

Looking at Ashley and Eric’s work, what is most striking is the freedom of movement within the discipline. They play with design tools, moving from analog to digital; they alternate and connect them to exploit their potential. They investigate limits and seek connections with the aim of obtaining an enhanced and complementary final result. They attempt to subvert the canonical order of the factors present within the design process. They reverse roles in an attempt to understand whether arranging elements differently helps the final result by breaking down the usual consequences.

They reconfigure standard design tools, pushing existing ones to their structural limits and trying to configure new ones. They jump from impromptu application to permanent, seeking underlying critical issues. They translate technologies and tools from one field of application to another, experimenting with new uses that were previously ignored or underestimated. They investigate different design scales, looking for connections between them, in a sort of fractal approach to problems in which the different design scales are actually different declinations and articulations of the same structure.

At a moment in history when some architectural firms are already turning their gaze to the Metaverse, whose design potential has yet to be defined and delimited, the work of Outpost Office continues to seek the relationship between analog and digital, between a rational approach to design and technological implementation, operating free from client specs with the sole ultimate goal of applied research.