Imagine a pristine cherry wooden frame that hangs still on a mustard wall through the years. Time passes, and fashions run with it, yet it seems not to age, it fits with the changes remaining intact. A timeless concept, that transcends places and generations, it is the holder of traditions, rituals, and old customs that continue to remain relevant and intrinsic to our everyday life, as well as in our society, shaping it effortlessly. From the way that it operates and works, to the way that we act and reason, as women, as people. That is femininity, or in better words, womanliness; a rather simplistic word to indicate a merge of qualities and attributes that society regards mainly as characteristics of women or girls.

Through the years, many thinkers have identified distinctive elements of a “conventional femininity” that propagated through mass and social media, and have a way to construct, perform and preserve gender. Beauty, demeanour, marriage and family arrangements, sexuality, and (White) race; allegedly these persuasive ideals most women engage with on an everyday basis, and they mutually allow to position the definition of femininity solely conceptualised from a Eurocentric and heteronormative perspective as traditional femininity ideology; but what about everything and everybody else? Are we sure that femininity only concerns women? And only a certain demographic? Clearly, it doesn’t.

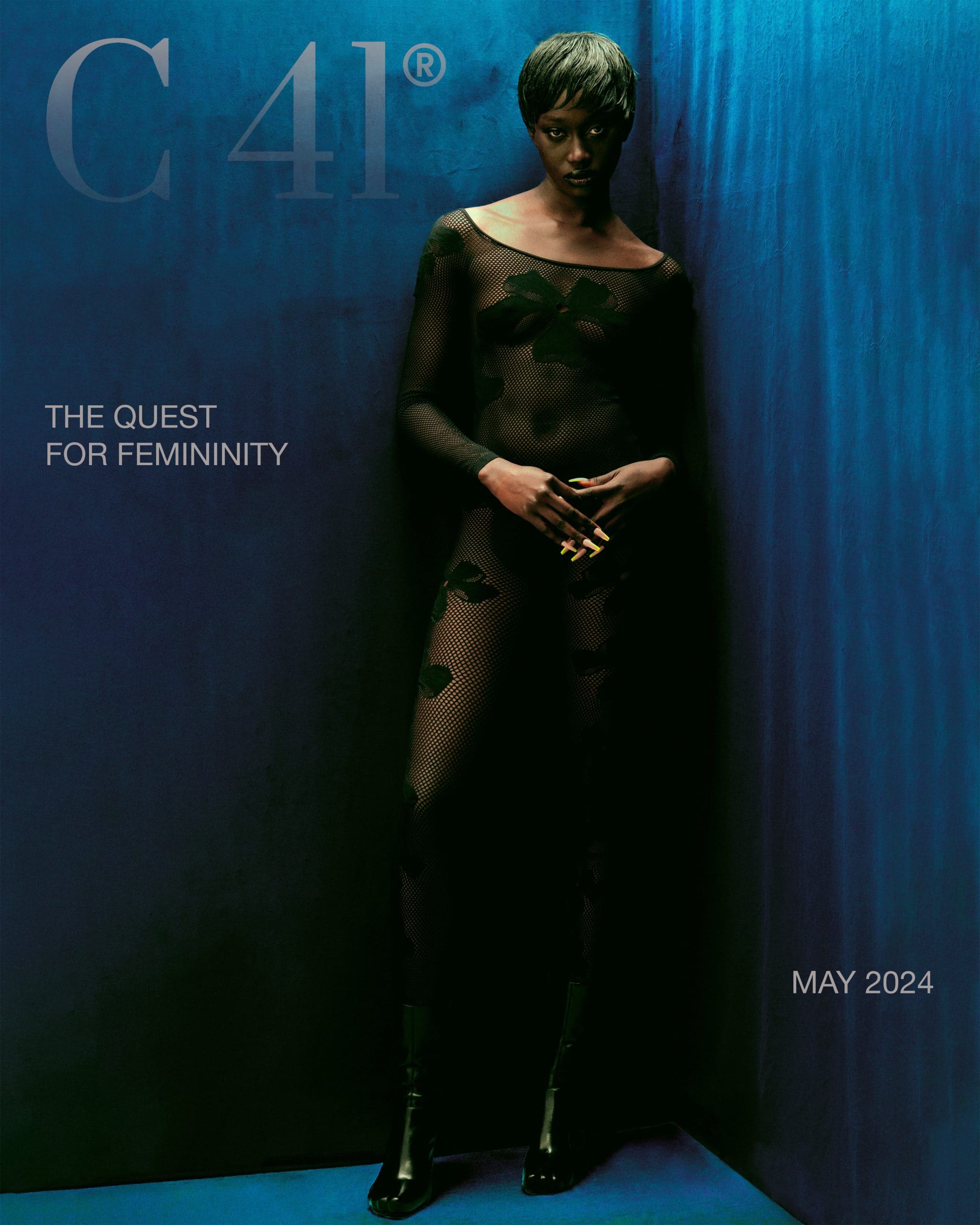

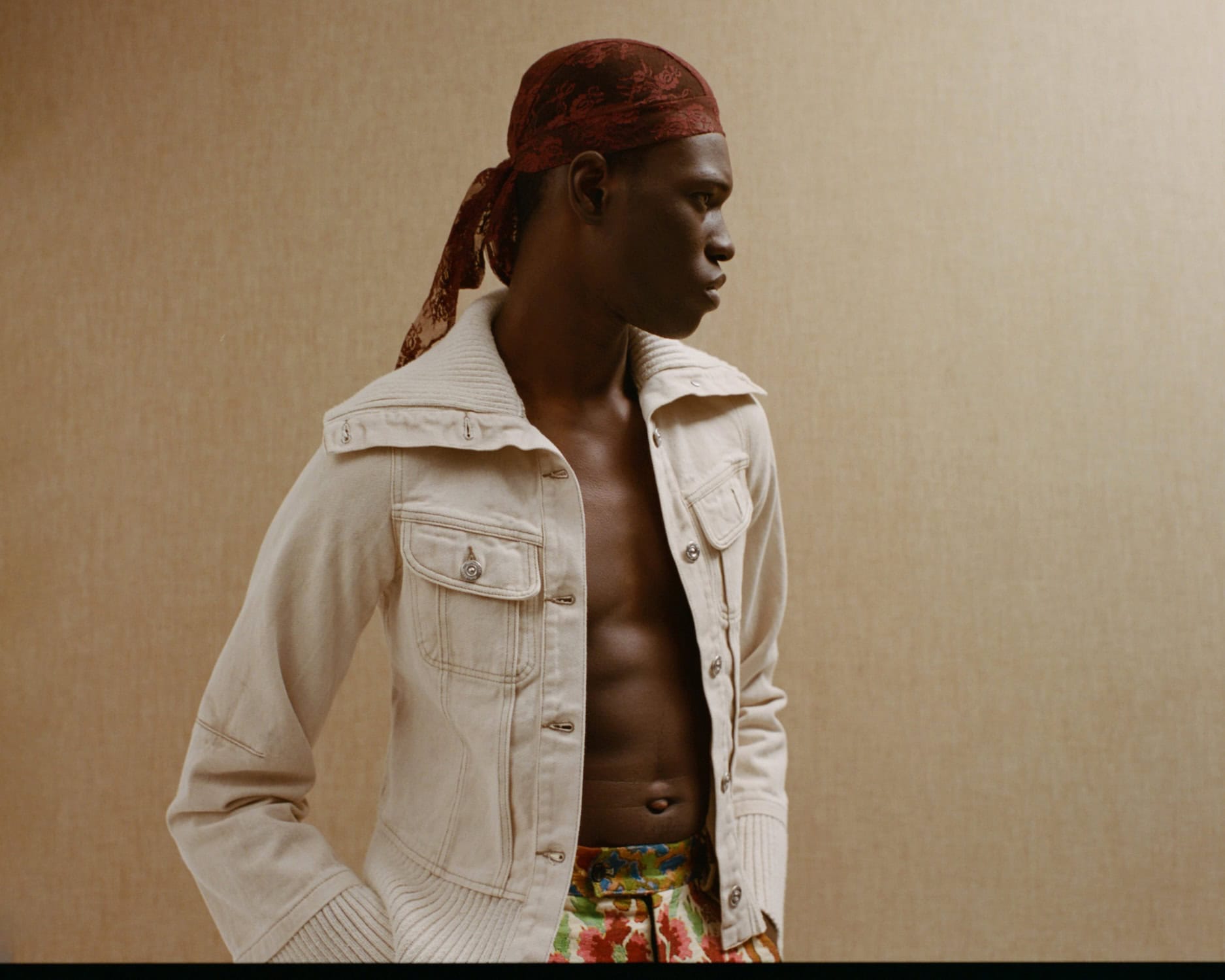

C41 Magazine’s May digital cover aims to reclaim the fluidity and ambivalence of the concept of femininity through the exploration of the stories of Nabou and Thiam. Two models, Italian and Senegalese, a man and a woman, are young, black, and with the adequate measures to start roaming around showrooms in hopes of being booked for some big shows, and eventually campaigns. Sooner than later they are about to become part of an ecosystem that has made conventional femininity an asset, a solid pillar, and yet something to which none of them abides.

Their fervent curiosity is tested by a language barrier, a culture barrier, a social barrier. Italian food may be exquisite, but it’s far from comforting compared to a warm plate of Tiep; people may be intrigued with Thiam’s story, and fascinated with Nabou’s hair––but how does one build community when they have little to nothing in common with its components? How does a woman affirm herself, when her womanliness still lingers between emancipation and foreign ideologies handed down through socialisation as an undocumented memory of the people?

How does femininity stand on these challenges? How can it stand on challenges such as migration, and the nurturing and preservation of one’s identity? Above all, how can it be used as a personal tool to remain grounded to whichever place one detaches from, but needs to carry with them?

Sister: “I remember when I was little, Thiam…”

Brother: “Yes, we were so happy in our little village, weren’t we? Every day felt like an adventure.”

Sister: “Mom made me feel so beautiful when she braided my hair. And those days when we danced under the sun… they made me feel invincible.”

Conventionally, for the vast majority of cultures, from East to West, hair is regarded as a symbol of beauty; something to treasure, to behold, one of those naturally given qualities that a woman owns to exercise her femininity. To African women, hair is special, dear, it is almost an extension of one’s self, whether it’s gravity-defying curls, a clean shaved head, or long plaits that differ in length and size. In a society that still hasn’t completely embraced black hair in the mainstream, Nabou’s journey, of holding Senegalese roots in Italy, as well as the visible changes in her looks, represent the ambivalence as well as the versatility of being a woman, a black woman, as well as an immigrant daughter of the diaspora. Her femininity transcends physical space and travels with her as her appearance evolves to adapt to new customs and surroundings, those of the West. As time passes, musings around local villages seem far gone, and Nabou has to learn to see herself through new eyes, while Thiam has to confront a new gaze that’s far removed from familiarity and that questions his strength.

Brother: “Yes, it seemed like everything around stopped just to admire you. I still remember when we danced to the sound of the drums, they made us feel alive. It was as if time stood still just for us. Now, look at us. We’re here, far from home, having to face these new challenges.”

Sister: “But even here, amidst all these challenges, I don’t want to lose my femininity. It’s part of who I am, where I come from.”

Brother: “I know, Nabou. You’ve always been strong, no matter where we are. And your femininity is a treasure that no distance can take away.”

Sister: “Thank you. I’m grateful for our memories, but also for the present. And I know that wherever the future takes us, we’ll face it.

Thiam appears nostalgic as he looks into the camera as if he is longing for tenderness, a sort of sweetness that is religiously found in Nabou but that seems to be lost when it comes to Thiam. The dynamic between man and woman is closely scrutinised through a brotherly love that sees femininity as a strength rather than a disability; something to behold, to treasure. A sentiment I deeply resonate with, coming from cultures in which womanliness is perceived as a powerful asset, but then seen and taken as a weakness, as something to hide, something you should keep from the world unless your desire is to get some attention or something at all. An outdated concept that again centers Western femininity ideologies forgetting the personal side of it, that involves and aims to foster a connection to one’s body, one’s mind, and one’s roots.

Thiam recognizes these aspects, as well as the challenges that he and Nabou will both have to face as their newfound home is a place in which concepts and opinions are mostly rooted in hedonistic principles rather than in spiritual practices and connectivity.

Once again femininity evolves. It assumes a new role, a new form, it becomes a tool, to communicate, to reassure. The softness longed by Thiam through his eyes, is found in his words, in the way he braids his sister’s hair, and in the way in which he acknowledges her womanliness, her own femininity as something extraterrestrial, not of the earth, that no matter the distance, or the places, can’t just be taken away.

The male gaze which is evoked through Thiam becomes an accomplice in the quest for femininity as it shifts from the usual observer to an active figure in the pursuit and the preservation of it, whilst embracing care and emotivity. Traits that we have come to recognise as being part of the stereotypical female but belong just as much to men, they belong to all humans.

In different ways, Nabou and Thiam embrace their own quest for femininity as they prepare to mould themselves beyond their roots, in a new space, in a new country that will soon become their home, and the new personas that these will demand from them. Femininity is their superpower.