In One Thread At A Time, Saskia de Brauw and Ira Bo braid distinct languages and tempos—the tactility of gesture and the stillness of the image, making and seeing. Curated by David Giroire and presented at 14 rue Pont aux Choux in Paris from October 7 to 31, 2025, the exhibition reads as a precise dialogue on contemporary weaving, where thread becomes material, memory, and cadence. In conversation, the artists outline a measured practice—layered, attentive—where each gesture, photograph, and interlaced strand composes a shared sense of time.

RITAMORENA ZOTTI: How did your collaboration for One Thread At A Time begin? Was there a specific moment when you realized your visual and material languages could intertwine?

S&I: David Giroire, the curator of the show, whom we both knew, introduced us. He saw a resemblance and a connection between our work as weavers, and he insisted we should meet. So we did. We met up over a coffee, but we’re not quite prepared yet, showing our work on low-quality imagery! Still, we realized that we had a lot more in common than we had initially thought. Those low-quality images stuck in both our minds. This is when our dialogue started to take shape. Although these works were created in very different ways, we both question the notion of values, especially the value of material.Someone’s trash is someone else’s treasure. It’s all about your perspective and what you decide to see..

RZ: The title One Thread At A Time evokes an idea of slow construction, a repeated, almost meditative gesture. What does “one thread at a time” represent for you? Is it a physical act, a symbolic gesture or a relational process?

S&I: ‘One Thread at a Time’ was inspired by a text David Giroire wrote about our work. We thought it was a beautiful title for our show, which began as a personal connection— It is like the flow of life, one step after the other, meeting people, creating connections, we move forward, we stop, we miss a beat, rigid, flowy, energetic, but we always keep weaving the tapestry of our life. Slowly, it becomes more expansive, perhaps with hole and frayed edges, but it’s always growing, one thread at a time. The exhibition starts from the notion of weaving but offers a contemporary interpretation.

RZ: How did you translate the act of weaving into visual, performative, or photographic terms?

SASKIA: I only weave with objects I find during my walks in cities, on beaches, and in forests. Except for the warp (if I use the loom), I choose linen and recycled cotton. I am very interested in using intricate patterns for both my paper weaves and my weaving with the loom. I enjoy the contrast between the dirty, sometimes unattractive material I use and these complex and detailed patterns. The size I work with is often dictated by the found material, which is mostly smaller and quite fragile.

IRA BO: I’ve been fascinated by the ancient idea of weaving my entire life. It took me some time to realize that everything I do—whether it’s creating a campaign, working on a book, designing a magazine, or working on music for a film – in my head I’m always weaving. I combine different ideas, people, and thoughts to create a tapestry that makes sense to me.

RZ: Your artistic dialogue emerges from very different practices, Saskia’s performative body and Ira’s photographic gaze. How did you build a shared language without erasing your individual differences?

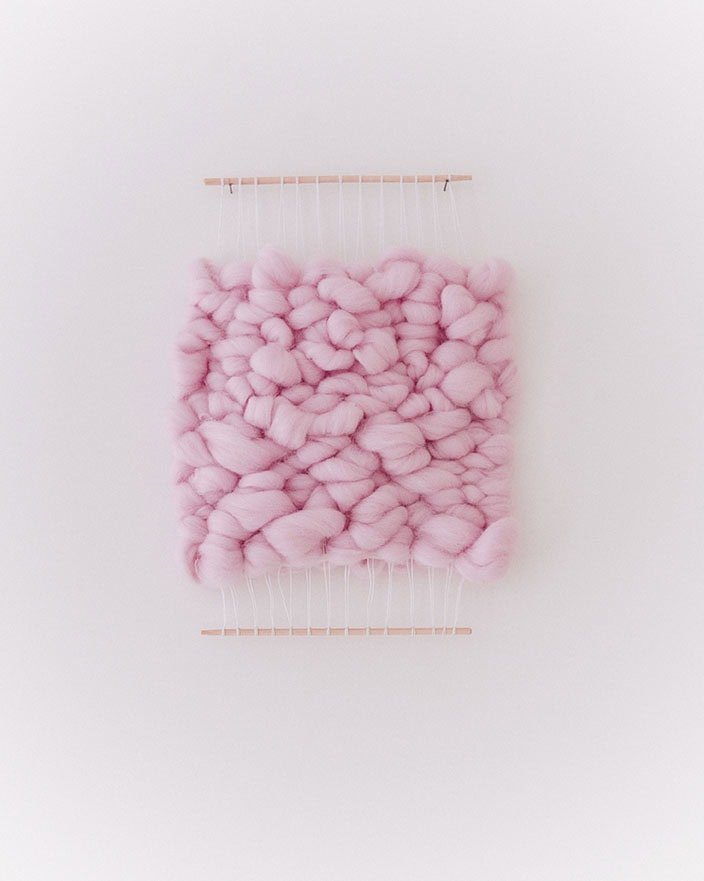

S&I: Again, it was because David thought our universes collided. The dialogue revolves around objects lost and found, repurposed; this is what first connected us. David also saw two lines crossing as Ira Bo started with more academic, exercise-like weaving, and now makes bold, almost abstract-looking shapes, whereas Saskia’s practice involves both creating paper weaves that appear more abstract and she also uses the loom and makes more traditional-looking patterns with unconventional material. We each have our distinct language and way of working, and there was never a moment when we needed to erase anything.

RZ: The exhibition unfolds in an intimate, by-appointment setting. How did this private context and David Giroire’s curatorial perspective shape the sequence of works, the spatial rhythm and your relationship with the viewer?

S&I: The beautiful space is Ira Bo’s husband, Clement Lesnoff-Rocard’s, architectural office and showroom. He had imagined creative projects happening there, but he hadn’t found the right fit yet. We feel very lucky that One Thread at a Time is having a first there. It is located on a busy street, and people often become curious to see what is going on inside. The space is small, but it has many interesting corners, mirrors, and windows to observe the work. Ira Bo’s works together almost create a spatial installation, and Saskia’s work is framed as it’s more delicate and fragile, asking the viewer to move close up to take in the details.

RZ: Could you walk us through your process using one key work as an example — from research and tests to set, post-production, and installation — including its dimensions, materials, production time, installation notes, and ideal viewing distance? Finally, if you had to leave visitors with a single lingering sensation, what would it be?

SASKIA: For me, it’s about working with found objects, basically trash. I gather worthless items from the street and see the beauty and potential in them. Sometimes I’m struck by their patterns, how they’ve decayed, or simply by the color or texture I was looking for. This is the foundation of what I do. I collect and then connect these items by weaving them into a single shape. I imagine that by doing this, I am connecting places and moments in time. Maybe, if people leave, they might feel inspired to reuse or value the things around them, whether objects at home or found on the street that they have forgotten about. Appreciate what we have, notice the beauty in small things, and realize that we are all connected to the world around us.

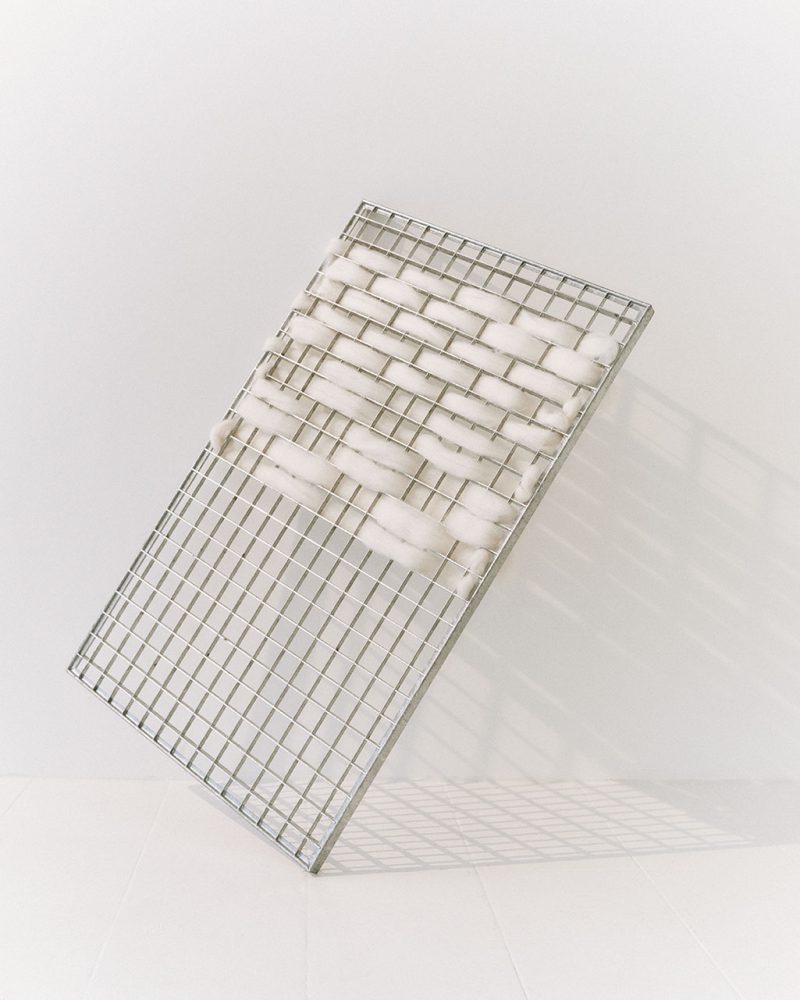

NORA/IRA BO: I discovered these aluminum blinds at a construction site and was immediately inspired. They were lying in a corner covered in dust and grime, but I was drawn to them like a moth to a light. I cleaned them one by one, and they became the perfect base for my weaves— malleable, soft, hard, and shiny. These are the qualities I look for in the materials I choose. With my work, I question the inherent purpose of textiles: they can protect, reveal, provide comfort, or even do the opposite. The more I strip away, the more they become tangible. For me, I would love for people to see the conversation, the dialogue. Our exhibition was conceived in this way. Opening the door (literally as well), we are able to spark a conversation with our viewer.