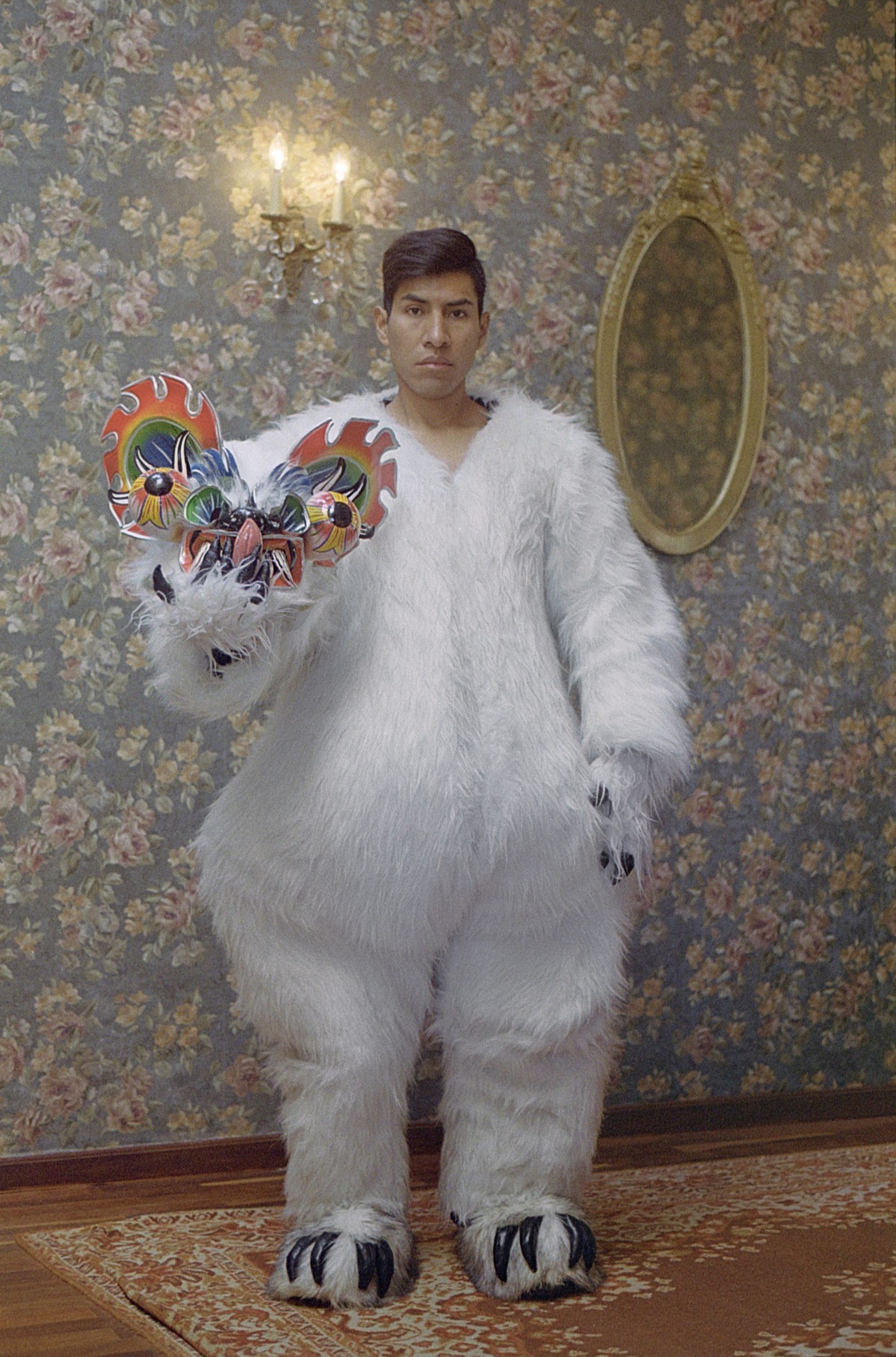

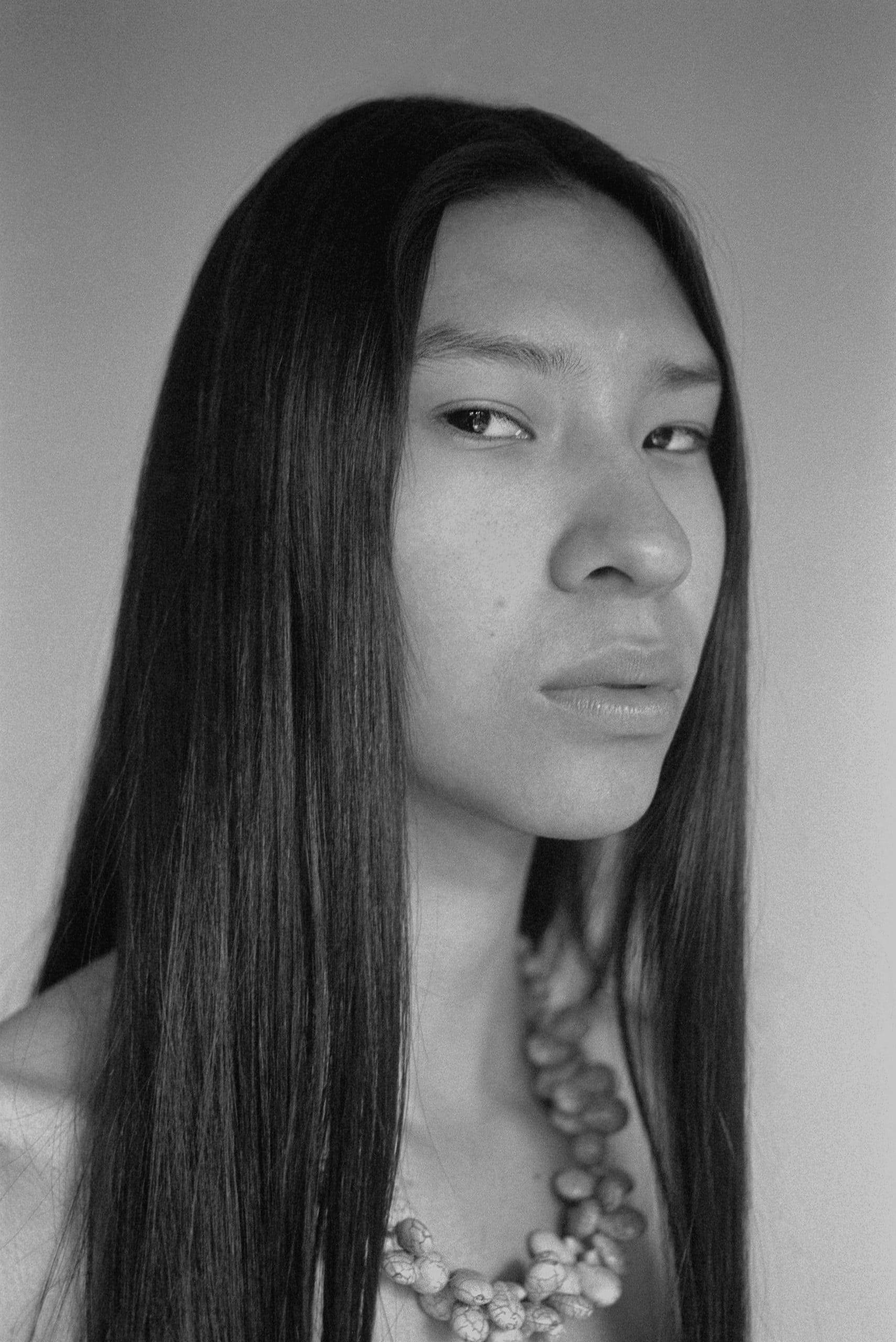

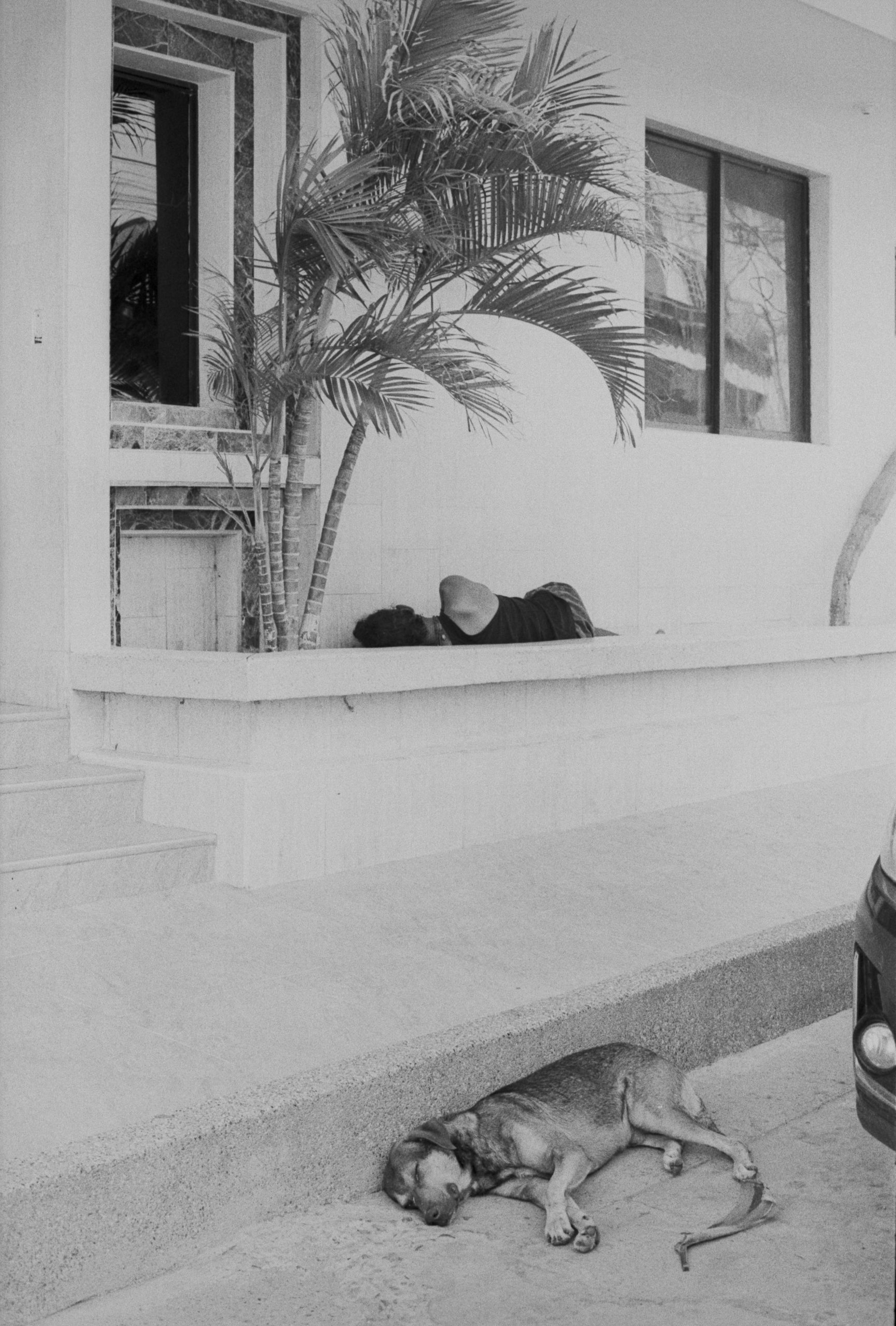

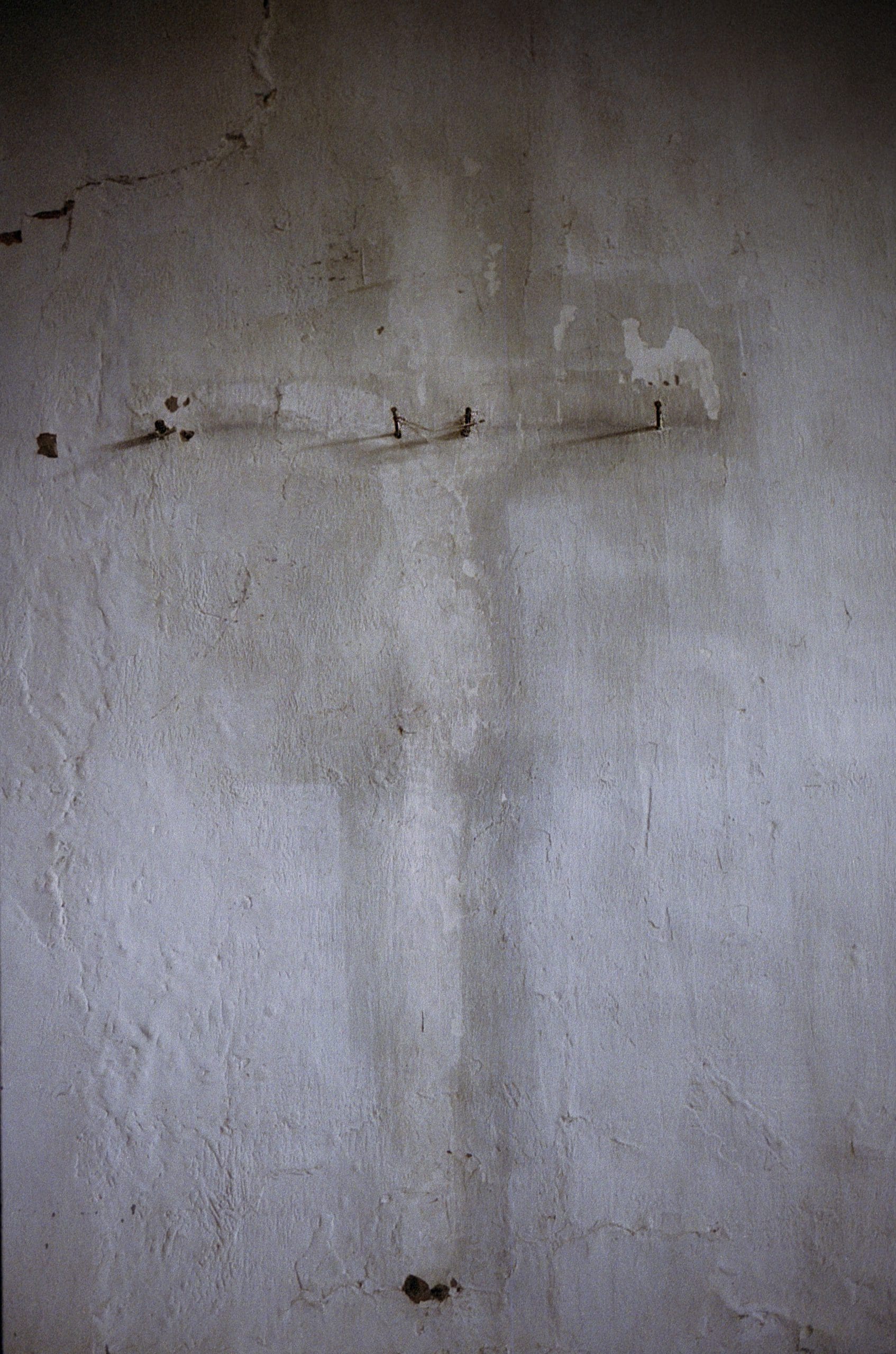

Marisol Mendez’s Padre delves into the concept of masculinity through a feminine lens, specifically focusing on dismantling traditional Latin American ideas of machismo. The project captures the intricate and often conflicting ways in which masculinity is created and presented.

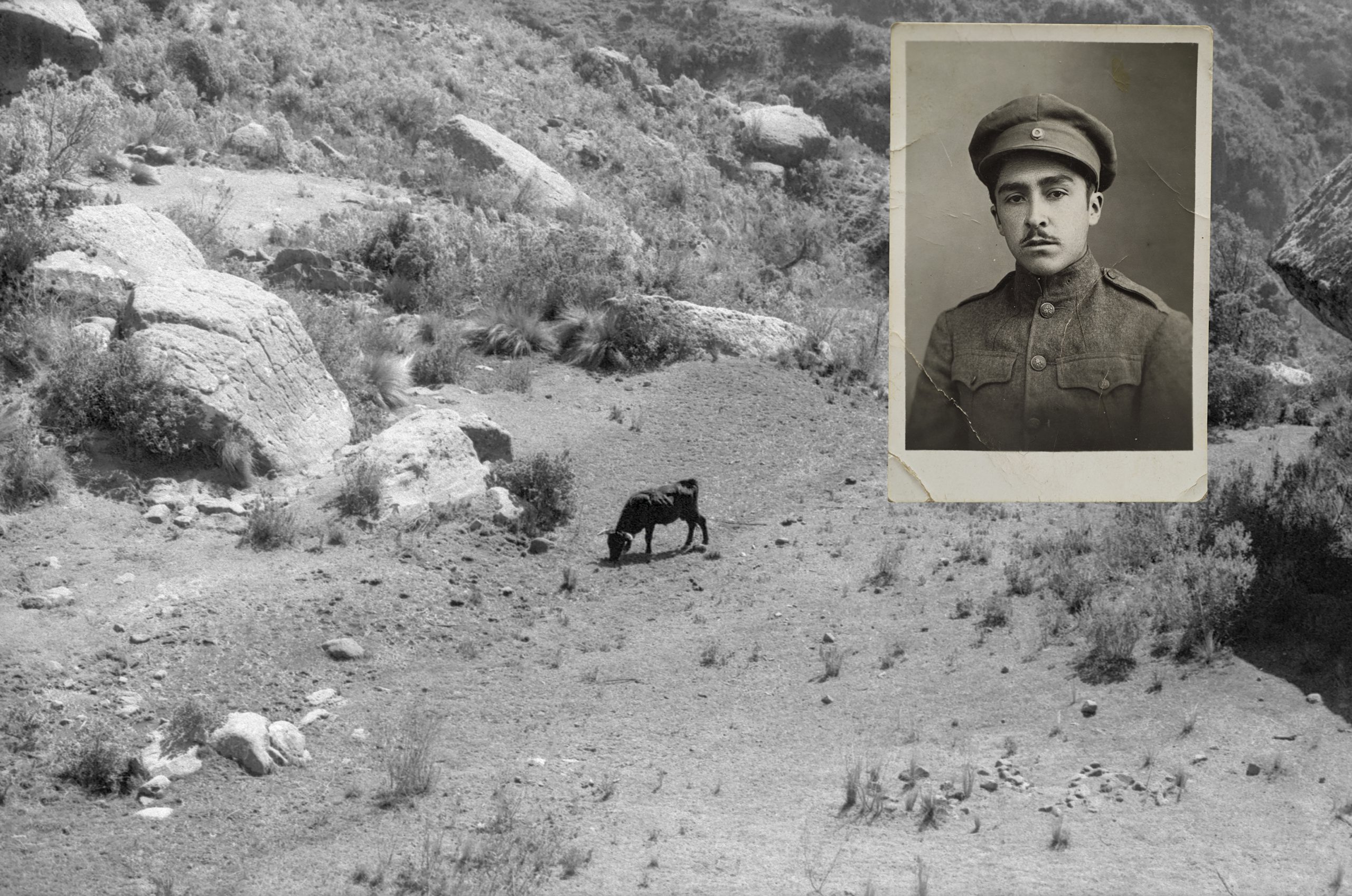

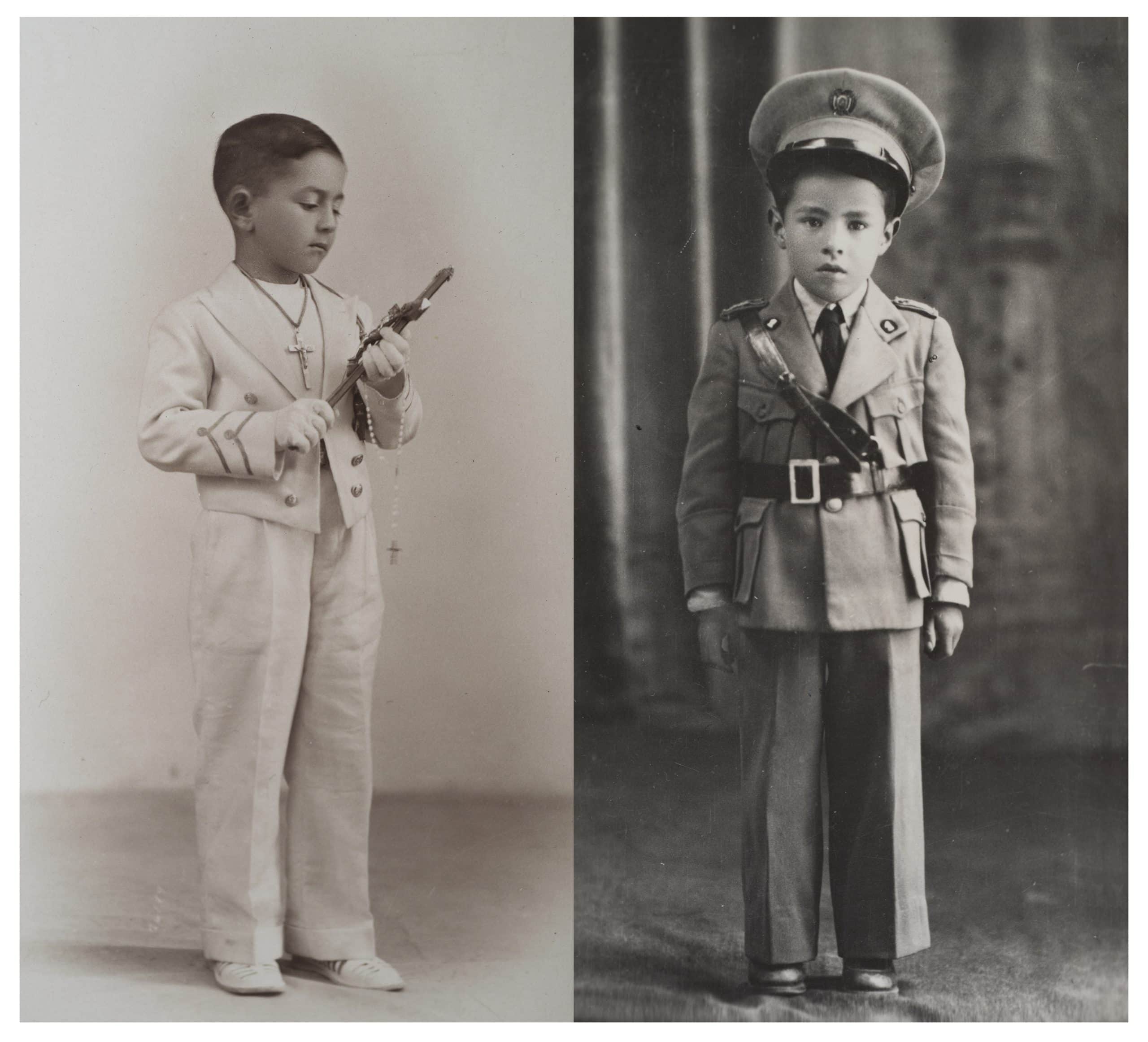

The project originated from a collection of letters that my late father left me. These letters contained my grandfather’s reflections on his role as an absent parent and offered guidance on navigating manhood to his sons. Through this correspondence, I gained insight into how different individuals navigate their relationship with masculinity, as it intertwines with violence, power, and patriarchal structures. Grounded in personal history and cultural heritage, Padre takes a critical look at the societal expectations placed upon men.

The act of hunting serves as a central framework in this exploration. Hunting, whether literal or metaphorical, embodies notions of conquest, control, and the exertion of dominance over one’s surroundings. By juxtaposing the nurturing and emotional aspects of fatherhood with this primal instinct, the project highlights the challenges men face in reconciling societal expectations of toughness and emotional restraint with their own internal struggles and desires for connection and intimacy.

Ilaria Sponda: How did you become a photographer? How easy or hard has it been in terms of facilities and support you got and didn’t get from your context of provenience?

Marisol Mendez: I discovered photography quite unexpectedly. Literature was my first love and words my conduit of expression so I thought my stories would unfold on the screen through scripts. However, I soon realised that composing a film required mastery of both language and images. I took up photography lessons to refine my writing and suddenly something clicked—pun intended. Photography captivated me for its demand for brevity and pause: you freeze time, telling a story in silence. The challenge is to encapsulate a universe within the frame which requires both precision and instinct. I’m interested in the poetic power of images and how they can shape reality into concrete forms. Through the lens of my camera, I embark on journeys into territories that would otherwise remain uncharted. Photography is the bridge that allows me to establish connections with individuals and situations that exist beyond the boundaries of my own experiences. It’s the tool that allows me to gain insights about myself whilst looking out. In Bolivia, photography faces a lot of limitations. Visually, it clings to that old school style of documentation and, in terms of working conditions, resources and incentives are scarce and infrastructure almost non-existent. In this sense, artistic projects can be difficult to execute. For example, many people here grow suspicious if I ask them for a photo and even more walk away without understanding the type of work I’m producing. I’ve also struggled to work with analogue processes because there’s no photography labs in my city. As an anecdote, I’ve had to fabricate my own negative holders from popsicle plastic wraps because you can seldom find any in Cochabamba. I also had to pause my projects for months on end because I wasn’t able to purchase film or get my camera fixed. On a positive note, this experience has taught me that bringing ambitious ideas to life relies more on resourcefulness than on having abundant resources.

IS: How does it feel to be among Foam Talents 2024?

MM: I’m delighted and honoured to be one of the Foam Talents 2024 ! It’s an exhilarating moment for me, and I can’t express how much joy and gratitude I feel at being recognised by such prestigious institution. I remember Foam Talent as the first photography prize I ever pursued. Back then, I was just starting to delve into photography, and I didn’t fully grasp its significance. However, with the encouragement of my photography teacher, who noticed my ‘eye for capturing moments’, I decided to go for it. I submitted an editorial shoot. My sister and I transformed a friend from drama class into Frida Kahlo with a clumsy styling that, in retrospect, barely resembled the iconic character. Nostalgia creeps in as I recall those images, a testament to my early creative endeavors. Yet, they also prompt reflection on how much my practice has evolved and the steps I’ve taken in the world of photography since then. Now I know Foam is at the vanguard of the photography scene, always in tune with the latest developments and innovations. It’s a wellspring of inspiration and a font of knowledge. Hence this acknowledgement not only boosts my confidence but also opens up doors to new opportunities, collaborations, and connections within the industry. The best part of Talents 2024 means joining a community of brilliant individuals who share the same passion and dedication to the craft as me. The opportunity to learn from and collaborate with them is invaluable.

IS: What project have you presented? How have you developed it?

MM: I presented MADRE and introduced my new and ongoing body of work Padre. MADRE project was born out of multiple frustrations. I was angry at the lack of nuanced representations of womxn, especially in a multi-ethnic and pluricultural country like mine. I was finding it hard to connect to my Bolivian identity and felt helpless in the face of machismo. MADRE was my way of addressing all these concerns. It allowed me to celebrate the diversity and complexity of my culture while raising questions about patriarchal rule and gender discrimination. Simultaneously, the project became the cathartic experience that allowed me to (re)connect to my female lineage and through it (re)imagine the history of Bolivia. Padre continues my explorations around memory, identity and mythology. The project explores the construction of masculinity from a feminine perspective. Focusing on deconstructing Latin American notions of machismo, it captures the complex and often contradictory ways in which masculinity is produced and performed. The genesis was a collection of letters my father left me before he passed. Within this correspondence, my grandfather grapples with his role as an absentee parent and imparts advice on navigating manhood to his sons. The exchanges provided me insight into how different individuals negotiate their relationship with masculinity as they navigate its entanglement with violence, power, and patriarchal structures.

IS: What’s your perspective on photography’s current state of the art considering promptography (also known as AI-generated images)?

MM: Promptography introduces a new dimension to photography, one where images are generated not by human hands but by algorithms. This raises questions about authorship, authenticity, and the nature of artistic creation in the digital age. While it offers exciting possibilities and challenges our understanding of the medium, it also highlights the importance of critical engagement with images and the recognition of their constructed nature. These new images are made up of information, expectation, and the phagocytosis of the history of photography. They function because we perceive them as photographs even though we know they are not. It is in the realm of reception rather than production where they hold a significant place. Without this gaze, they would not exist. But we look at them and confuse them. And each time, we do so with increasing precision. In this context, photography’s current state can be seen as both dynamic and complex, characterized by a convergence of technology, artistry, and interpretation. As we navigate this evolving landscape, it becomes essential to consider not only the technical capabilities of AI-generated images but also their cultural and ethical implications.

IS: Do you feel like there’s an overall global visual language when it comes to documentary photography? What’s your personal approach to it?

MM: The traditional approach to documentary photography was often rooted in a straightforward and objective representation of reality, aiming to capture a moment or subject with minimal intervention. Photographers believed in the photograph as an unaltered record of truth, reflecting a linear and singular narrative.

In contrast, I prefer a more contemporary or hybrid; one that acknowledges the subjective nature of image-making. I recognise that photographers bring their perspectives, biases, and creative choices to the process, resulting in a more complex and layered representation of reality. I embrace a fusion of traditional documentary practices with elements of subjective storytelling, incorporating diverse perspectives and responding to the evolving nature of truth in the digital age. This shift reflects a departure from a rigid adherence to objectivity towards a more nuanced and dynamic understanding of the medium where the photographer role is that of an interpreter rather than a teller of reality.

IS: What’s your positioning in regards to words and images interconnectedness? Do you feel like images need words to be explained? If so, why?

MM: I believe that although images and words can stand alone, their interconnectedness often enriches communication, offering a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the message being conveyed. Images can be open to multiple interpretations, and words serve as a means to guide viewers towards a particular understanding or narrative. Additionally, they can provide depth, nuance, and specificity to the message conveyed by an image, offering layers of meaning that might not be immediately apparent through visual representation alone. The relationship between words and images can be symbiotic, with each enhancing the impact of the other. Words can lend authority and credibility to images, while images can make abstract concepts more tangible and accessible. However, it’s not necessarily the case that images always require words for explanation. Some images may possess inherent clarity or universality that transcends language barriers, communicating effectively without the need for accompanying text. Furthermore, it’s important to recognize that text can anchor the meaning of an image, erasing ambiguity. When elements within an image are partially obscured or unclear, viewers are prompted to engage in deeper analysis and interpretation. This opacity invites viewers to question assumptions, consider alternative perspectives, and interrogate the underlying meaning.

Marisol Mendez is a photographer and researcher from Cochabamba, Bolivia. She uses the photographic medium to study the tension between truth and fiction, the tight relationship between what a photograph creates and the (sur)real it comes from. Driven by research-led and self-initiated projects, she seeks to deconstruct traditional modes of representation and weave nuanced narratives with multiple layers of meaning. At the heart of her artistic pursuit lies the exploration of humankind. I’m moved by the desire to build genuine connections with the people on the other side of the lens. My objective is to encapsulate the intimacy of shared experiences, the tenderness or friction of mutual recognition. Embracing the horizontality of images, she utilises a diverse array of visual languages to tell stories that traverse the boundaries between individual experience, collective memory, and imagination. Rooted in the landscapes and folklore of her culture, her work oscillates between candid and staged, naturalistic and mythical. Ultimately, she wants to challenge preconceptions, spark dialogue, and prompt viewers to reconsider their perspectives on reality and representation.