«I’ve never travelled all that far». Thus begins one of Luigi Ghirri’s first writings, Cardboard Landscapes, published in the magazine Il Diaframma/Fotografia Italiana in 1973. A very simple sentence, when read today, though, in the light of his photographic work and the splendid short texts that have accompanied it throughout his artistic career, it sounds more enigmatic and ambiguous than it may appear at first glance. Which travels? Far from where? A first response might be sought in geography. Luigi Ghirri, one of the artists who left a significant mark on Italian photography in the past 50 years, was born in Scandiano, near Reggio Emilia, in 1943, and passed away unexpectedly, only 49 years old, in his house in Roncocesi, a few kilometres away in the Reggio countryside. Over the course of a short but extraordinarily prolific lifetime, he mostly travelled in Italy, occasionally in Europe and the United States. There is no trace of any other continent in his imagery, not a hint of exoticism. As is known, he loved minimal adventures, Sunday jaunts, often within a short distance from home. Not all that far, therefore. Through his work, however, Ghirri has also travelled extensively across maps and the pages of the atlas, he has crossed miniature landscapes and painted landscapes, commercial reproductions and postcard views, by means of objects he has taken extraordinary trips without leaving the domestic space, journeys of the mind and memory, and this is how kilometric geography starts to creak and fracture before him, unable to include the extension of his movement. This simple sentence, which opens the precious collection of his writings — whose dense and evocative title, There is Nothing Old Under The Sun, reverses the well-known Ecclesiastes quote «nothing new under the sun» — therefore betrays, or, perhaps, secretly reveals from the get-go, a complexity that should not be sought in the images or words themselves, but in the conceptual perspective in which they are integrated, and the deep and highly aware intention with which they were captured or written.

Small and large, simple and complex, internal and external, in frame and offscreen, past and future, memory and a gaze on the present — from the very beginning, both in his photography and the accurate theoretical considerations that accompany it, Ghirri’s work appears as a crossroads, the point where opposites intersect, without any presumption of resolving these extremes nor of confining them into a single response to the complexity of reality. Quite the opposite. From the very start and throughout all his research, with great coherence and sobriety, photography remains for Ghirri a way to see, to think, to express his vision of the world and to address the landscape around him with a fresh gaze, full of childish astonishment and wonder. «Right from the start», he writes, «I saw in photography a great adventure, both of thought and of the gaze, where the camera is a great, magical toy, capable of bringing together the great and the small, illusions and reality, time and space, our adult awareness and the fairy-tale world of childhood». And, in an interview, he adds: «Photography is an enigma». It is, in fact, the enigma of photography, since, unlike a problem of any kind, photography has no solutions. It is both a testimony to what we see and a reinvention of what we have seen. To Ghirri, taking a picture means making one’s perception of the world visible. And from Daguerre’s very first plate to the present day, the enigma of this impossible image remains unsolved. As a matter of fact, that mysterious and almost magical coexistence of reality and fiction, of presentation and representation of the world, that opportunity to see something that is no longer there and the sensation that something else is about to happen persists in every photographic image, as source of wonder and turmoil. A double vision, as Ghirri calls it, the gap in perception that simultaneously lies «at the frontier of the already seen and that of the never seen».

«My duty is to see with clarity», he writes in 1978 in the critical text that prefaces his first book Kodachrome. As others that follow, the book is not a point of arrival or closure, but the opportunity to bring together and re-read a selection of images shot in previous years, some of which already gathered in other projects. However short, the text marks a first important step in the articulation of Ghirri’s poetic vision. The image of the earth seen from the moon with which it opens, that «first photograph of the World» taken from a spaceship, an image never seen before, is very precious to him, so much so that it appears in his writing and interviews on several occasions. By offering humanity a vision of the whole, this image «that contained all other images of the world: graffiti, frescoes, paintings, writings, photographs, books, films» — both the sum of all the images that had come before and a mysterious total-hieroglyph to be deciphered — is also revealed as the place in which the overlapping common scales of spatial, temporal and perceptual measurement make the gaze impossible. What is to be done? Faced with the attraction and vertigo of the infinitely large and the infinitely small, driven by «the desire and the need to interpret and translate the sense of this sum of hieroglyphs» simultaneously present in the analogue-duplicate of the world, Ghirri rediscovers and claims for himself a space for the infinitely complex – the space of the man, of the photographer, with his experience and gaze on things. Complex and inevitably fragmentary, partial, uncertain, just like photography which selects parts of reality and isolates them from their context yet cannot disregard what lies outside the frame. For Ghirri, the things that are not photographed are just as important and true as those captured in the image. And just as there is no one truth, no one way to depict things, so too our perceptions cannot be harnessed in strict categories, they have the shape of fragments and annotations, they are sensitive to the light, to the moment, to the landscape. «Perhaps this is why scattered fragments, intuitions, slight changes in light, the shade of a colour, the detail of a façade, a sound picked up, are transformed for us into small certainties, into a totality of points to be put together, to trace a possible itinerary – like Tom Thumb’s stones, guiding him back home», he writes in Scattered Landscapes in 1987. The rigid dichotomy between professionalism and artistry is blurred, as the limits between knowledge and poetics, categories that were hitherto deemed irreconcilable.

An important, not to say crucial, leap in the Italian cultural scene of the Seventies and Eighties. As Arturo Carlo Quintavalle — the critic who, in 1979, along with Masimo Mussini, co-curated Vera Fotografia, the first important anthological exhibition of Ghirri’s work at the Galleria della Pilotta in Parma, which was a crucial turning point in his research — wrote, until that moment «photography scholars had tended to clearly divide images into two categories: on the one hand the amateur photo, or the commercial photo, in short, the mass photo; on the other hand, the art photo, the photo for the elite». The critic wonders how these two poles may now be reunited in the work of a single photographer. The answer lies in Ghirri’s crystal-clear awareness that he wanted to escape any established categorisation, and in his constant commitment «to seek an image in equilibrium, suspended between detection and revelation, between the interior and the exterior». From the very beginning, in fact, in search of a new image, able to contain these two extremes, his work has knitted closely and merged “low”, routine photography, which follows the path of well-known and immediately recognisable visual codes, with “higher”, or so-called creative, imagery. The change of posture is intellectual, even before than related to the photographic gesture itself. The shot, for Ghirri, is first and foremost mental, before being mechanic. The photographer positions himself in front of reality armed with his own past and memory, he is the result of a multitude of stimuli and intertwined layers of experience, the vehicle of an expanded temporality that projects the already seen into the present moment, in order to rediscover it. Therefore, the awareness that other images — cinematographic, literary, creative and musical — converge in the shot, is inscribed into the photographic image, even before it ever comes to light. As Gianni Celati, writer and Ghirri’s travel companion, says, «his idea was that every image recalls another image, because there is no unique and original image. Every image brings with it traces of recognition of something else, other images, photos, visions, apparitions…». Traces of a language that is sensed rather than enunciated. Photos as testimony of an ecstatic way of looking, charged with renewed wonder and enchantment day after day, where time and space are physical and existential coordinates that organise the work over the course of years, saving it from rigid classification cathegories, transforming the archive and the project titles into a splendid reservoir of images and possible stories. For Ghirri, every photograph demands renewed attention, it has absolute autonomy, and more than an expression of permanence, it is the extraordinary and ephemeral materialisation of an event. But like the letter of an alphabet, like the tiles of a mosaic that is at once subjective and extraordinarily universal, every photograph is also part of a whole, of a wider “system”, of a narration in progress, in which the cards can be picked up again over time and reshuffled into the game in a new way with every different combination and narrative arrangement. «I’ve tried not to get caught up in trends or genres, and for this reason I have tried to work in various different directions simultaneously, to allow for a continual process of thought and cross-fertilisation. My aim is not to make PHOTOGRAPHS, but rather CHARTS and MAPS that might at the same time constitute photographs», he writes. No surprise, thus, that on several occasions, when discussing his work, he mentions a story by Jorge Luis Borges, which tells of a painter who spent his life painting scenes of rivers, trees, animals, landscapes, only to realise on his deathbed that all the images he had ever painted ended up composing a single, larger image: that of his face.

«Ghirri’s images sing, and if we look at them well and for a long time, we drift away in daydreams as though captivated by the sound that animates them. We ask ourselves: but where have I seen all this before? Childhood is the magical place where all the images that strike us without hurting us, that come to us without ever upsetting us, reside», writes Marco Belpoliti. His consideration draws on the pairing of memory and childhood at the centre of Ennery Taramelli’s book Memoria come un’Infanzia. Il pensiero narrante di Luigi Ghirri, which goes hand in hand with that other childish element par excellence: enchantment. That feeling of being in the world, to use Celati’s words, wonder and amazement at everything there is around us, «like the idea of something that bursts into everyday life, precisely where we thought all mystery was banned». «I think that is all you can ask from a poem, a painting, a song, a photograph», Luigi would have said. Ghirri took pictures of ordinary things, everyday things, domestic things, forgotten things, in short, all those things that our eyes, anaesthetised by habit or saturated with too many unnecessary images, are no longer able to see. However, still in Celati’s words, his photographs teach us that the world takes shape because there is someone to observe it. It takes shape when somebody feels the need to contemplate it. Not to invade or massacre it to get ahead… This brings to my mind La Discrétion. Ou l’art de disparaître, the essay by French philosopher Pierre Zaoui that I translated into Italian a few years ago. Discretion, for Zaoui, is that peculiar, intermittent, low-volume art of knowing when to take a step back, to withdraw from oneself for a moment, to get lost in the crowd and in things, it is the silent joy of observing, unobserved, the world. «Discreet souls», he writes, «are the foundation of the world: without them there is nothing left, just empty mirrors; without them, nothing holds but formless matters». There is great discretion, a great ability to listen, a sincere affection for things in Ghirri’s photography.

But beyond the wonder endlessy renewed in front of his images, at once always new and yet already seen, and the sense of profound familiarity and subtle amusement that emanates from them, what I most love about Ghirri’s work is his splendid concept of open work, of a reservoir series, the idea that photography is able to freely follow the unpredictable associations dictated by chance and memory. A path with a shifting, zigzagging itinerary, which starts from a simple line but then branches out, questions itself, retraces its steps, embraces the past and anticipates the future, opens the project up to chance and stimuli, so as to create, over time, an ever larger drawing, a real travel map.

In one of his short critical texts, precisely entitled The open work, written in 1984 and soon translated to French and published in Les Cahiers de la Photographie in 1985, Ghirri describes in fact how the idea of a single large artwork came to him while recollecting two books he had loved as a child: the family album and the atlas. Two simple books, two domestic objects that were found in every home before the invasion of digital technology, and which, as he wrote, «contained two categories of the world and represented it in a way that I understood. Inner and outer, my place and my history, the places and the history of the World». The search for unity and completeness, as well as the awareness of the irreducibility of reality and its mysteries, arise precisely from the desire to reconcile this dualism and to embrace opposites. «Perhaps it is very simply the idea of constructing a book, or better a sort of Personal Atlas – a perfect symbiosis of the two books of which I spoke».

This passion for atlases and journeys across maps, a mental gesture beloved by many writers and generally by all humans from a very early age, remained with Ghirri throughout his life. «To a child who is fond of maps and engravings / The universe is the size of his immense hunger. / Ah! how vast is the world in the light of a lamp! / In memory’s eyes how small the world is!» wrote Baudelaire in The Voyage, the poem that concludes The Flowers of Evil. For Ghirri, the atlas is truly «the book, a place where all the features of the Earth, from the natural to the cultural, are conventionally represented: mountains, lakes, pyramids, oceans, villages, stars and islands». So much so that in 1973 he expanded various details from different maps to create the Atlante series, a true journey into signs, inside the image, into the place that paradoxically erases the journey itself, since every possible movement is already described, each itinerary already traced. In a similar vein, in 1974 Ghirri photographs the sky every day, as though keeping a diary (Infinito), and in 1979, he does the same with the books and records of his library, a fragmentary and allusive self-portrait through objects that composed the Identikit series. These are only a few examples of the unceasing research of those years, and of his innovative poetic posture.

And it is precisely from the perspective of key concepts such as open work, archive-reservoir, atlas and biographical landscape that Ghirri’s long and fruitful relationship with architecture and landscape should also be understood.

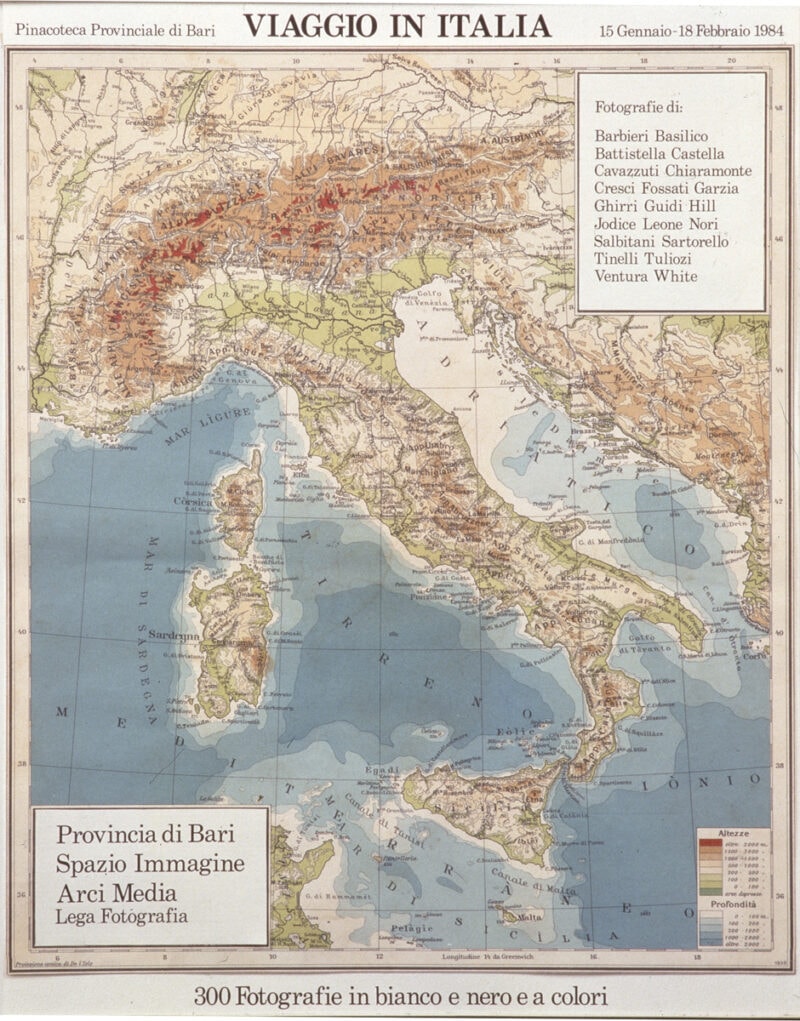

In the early Eighties, in fact, the reflections on photography he had developed over the previous decade converged into a series of works dedicated to Italy. After countless stray wanderings near his home, as they were called by the artist and friend Franco Guerzoni, who for some time accompanied Ghirri on these trips; after some important public commissions, which allowed him to intensify his exploration of the area, and the beginning, in 1983, of his long-lasting and seminal collaboration with the Milan based magazine Lotus International, directed by Pierluigi Nicolin — in 1984, along with photographers Gianni Leone and Enzo Velati, Luigi Ghirri curates Viaggio in Italia, an itinerant exhibition that started in Bari and eventually reached Reggio Emilia, which became the manifesto of what later took the name of the “Italian school of landscape”. A real “refoundation” project of Italian landscape imagery and Italian photography at the same time, that includes 20 photographers — Olivo Barbieri, Gabriele Basilico, Giannantonio Battistella, Vincenzo Castella, Andrea Cavazzuti, Giovanni Chiaramonte, Mario Cresci, Vittore Fossati, Carlo Garzia, Guido Guidi, Luigi Ghirri, Shelley Hill, Mimmo Jodice, Gianni Leone, Claude Nori, Umberto Sartorello, Mario Tinelli, Ernesto Tuliozi, Fulvio Ventura, and Cuchi White — along with a writer, Gianni Celati, and a critic, Carlo Arturo Quintavalle. From the beginning, the project also entails an eponymous book, which Paola Borgonzoni, Luigi’s wife and precious collaborator, designs for Il Quadrante publishing house. On the cover, one of those maps hanging in classrooms, used over the years by countless young Italians to travel far and wide without moving. In an interview with Ghirri published on the newspaper Il Manifesto in 1984, shortly after the inauguration of the Bari exhibition, Marco Belpoliti clarifies that Viaggio in Italia was not a group exhibition of photographers but rather «the first attempt to take stock of the image of Italy produced by the mutations of the Sixties and Seventies». And how it was neither a documentary exhibition, nor yet another show of photojournalism, but «a journey into the visual imagination of our country». This explains the curator’s decision to include other forms of representation beside photography, such as Celati’s writing, Towards the River’s Mouth — which reads alongside the photographs in the book — and Quintavalle’s critical introduction.

I find the choice of the title Viaggio in Italia both emblematic and particularly interesting, and this for two reasons. The first and more obvious one is that while the image of the renowned Grand Tour is explicitly evoked — the 17th and 18th century coming-of-age journey that aristocrats and intellectuals from all over Europe (including Goethe, the two Shelleys, Stendhal… ) would take to discover the wonders of the Belpaese — although, not without a certain irony, the material presented actually goes in a completely opposite direction. Viaggio in Italia from 1984 is in fact a journey of research and discovery of whatever lies in the middle, often forgotten or unseen, between the names of famous places highlighted in red on the map, between one picture-postcard scene and the next. The second reason that, in my opinion, gives the title its extraordinary density, is the silently enigmatic nature of the two words which compose it, Italia and Viaggio. Both individually and together. Because if each journey for Ghirri is always inseparable from the thinking process, then it is first and foremost a mental state more than a physical one, it is a gesture to understand the world, to perceive and to discover it — And if, as he wrote, travel is synonymous with adventure, and, «whether great or small, this adventure may only be experienced by straying off the beaten track, evading the clichés, and instead seeking out new visual pathways and new strategies through which to represent them» — And if Italy is undoubtedly a nation, a geographic region yet also a multilayered space shaped by historic and cultural stratifications, a country formerly exalted by classical painting and literature, partly rediscovered thanks to post-war cinema, partly dismissed, but generally confined in a traditional iconography, trapped in the stereotype of tourism and in the “common place” that results from a myriad of accumulated visual clichés, until it becomes impossible to watch — Then, when juxtaposed, those two words perfectly blend the idea of experience and that of geography, a pairing of which Ghirri was very fond from the beginning, the crucial intersection where a sentimental geography and a new way of looking at the landscape become possible.

In Viaggio in Italia, the material is punctuated into 10 chapters and I think it is worth listing their titles, first and foremost because they are truly beautiful, and then because, open and evocative as they are, they elude all banal or predictable categories and give voice, on their own, to an incredible declaration of poetic and intents: As far as the eye can see / Seaside / Margins / Local Life / End of the Line / Downtown / On the Threshold / No One in Particular / Closed at Sunset / Giotto’s O.

Viaggio in Italia is therefore primarily a suggestion of method, an open question, an attempt to clear our gaze, a quest for the identity of the present, in the present. Far from taking anything for granted, in this great choral adventure every photographer-traveller stands as a participating observer before the landscape, each of them relates to it with wonder, curiosity, affection, searching a new point of view on things, becoming the shifting link between the subjective and collective imagination. Goodbye local folklore, goodbye “beautiful landscapes” and romanticism. Embracing the monumental in everyday life, inscribing the extraordinary classical heritage in the imperfection of the present, the photographers involved in the project immerse themselves in suburban and rural areas, they rediscover out-of-the-way spots where nobody would ever stop to look around, they cover those thousands of kilometres that have been waiting to become part of the contemporary narrative, they bring together in a single image the great beauty of tradition and all the rest, which is in reality what has always happened, spontaneously and silently, in the eyes of the people who live in those places. And so emerges a minor Italy, or, rather, «the boundless landscape that traditional iconography, the stereotype of tourism, and the weekly and monthly magazines, more or less glossy, have removed or hidden». «The present was missing! And I wanted the present!», exclaimed Ghirri in an interview.

Invited to recall his experience, in the text Viaggio in Italia con 20 fotografi, 20 anni dopo writer Gianni Celati recounts how the sobriety of images was the specific style of this research on landscape, shared by everyone involved in the project. Liberated from the idea of having to bring back an exotic or aesthetic loot, or even of having to be the result of a perceptive immediacy, in very Ghirri-esque fashion the photographs of Viaggio in Italia make space for a «vision that no longer believes in the rapid capture of things, but rather seeks a way to perceive-imagine the external world in its duration and continuity». There is very little human presence in the images, the framings are less “set-up” and more estranging, «as though things finally appeared enveloped in their natural silence». A photography that moves towards pure happening. Therefore, in a similar way, and in tune with the images, the short story with which Celati contributes to the project is the result of a year and a half of live recordings across the territory, it is made up of diary excerpts, snatches of conversation collected in the field, and notes on whatever he saw while travelling with the photographers. Even beforehand, during the two or three years that preceded Viaggio in Italia, when he wandered through the Emilian countryside with Ghirri, while taking notes the writer would repeat to himself: «This is not literature, it is not literature, it is a reportage on the vision we have of the places». Reportage… Vision… Again, two words in which there is space for Luigi’s much loved opposites: internal and external, subjective and objective, the immediacy of the present and the stratification of experience. In fact, as he once said in an interview: «after all, my work as a whole is probably not the objective geography, if such a thing exists, rather it is a journey, as I mentioned before, into a chosen landscape and, as such, I consider the ‘inhabited space’ to be the typical landscape of Italy».

In the years following Viaggio in Italia, Ghirri continues his fact-finding adventure in the Italian landscape, accumulating a wealth of material that, from time to time, he organises into an exhibition or a book. Through Ghirri, by no means isolated but certainly a unique and exceptional figure in the past 50 years, and thanks to his gaze, reality has been turned into one great narrative, the places and objects photographed are crystals of space and time, memory zones dense with signs and enigmatic meaning, open to dialogue.

The extraordinary legacy of Viaggio in Italia in particular and, more broadly, of Ghirri’s work is perhaps precisely the desire to keep gazing at the world so as to rediscover it and reimagine it every time. And if photography, both a geometric and sentimental system of measurement, is to be understood, as he suggests, as a cognitive tool to think and comprehend reality, the search for a new way of looking should always coincide, even today, with a silent renaissance of the gaze.

References and background readings:

Luigi Ghirri, Paesaggio Italiano/Italian Landscape, Quaderni di Lotus, Electa, 1989

Luigi Ghirri, Niente di antico sotto il sole, edited by P. Costantini and G. Chiaramonte, Sei Editore, 1997

Luigi Ghirri, Lezioni di fotografia, edited by G. Bizzarri and P. Barbaro, Quodlibet, 2010

Luigi Ghirri, The Complete Essays 1973 – 1991, MACK, 2016

Luigi Ghirri. Il paesaggio nell’architettura, edited by M. Nastasi, Electa, 2018

Gianni Celati, edited by M. Belpoliti, M. Sironi and A. Stefi, Quodlibet, 2019

Pierre Zaoui, L’arte di scomparire. Vivere con discrezione, Il Saggiatore, 2015

Matteo Bellizzi, Interview with Gianni Celati, Doppiozero, april 2011

Marco Belpoliti, Viaggio in Italia, Doppiozero, july 2012

Marco Belpoliti, Luigi Ghirri and Gianni Celati, Doppiozero, august 2016

Marco Belpoliti, Luigi Ghirri: memoria e infanzia, Doppiozero, january 2018

Davide Ferri, Viaggi randagi con Luigi Ghirri. Il racconto di Franco Guerzoni, Artribune, october 2014

Chiara Paterna, Gianni Celati and Luigi Ghirri. Geografie dello smarrimento, Pangea, march 2020

Biographical notes:

Alice Guareschi (1976) is a visual artist and researcher based in Milan. Her practice includes writing, sculpture, filmmaking and literary translation. She holds a MA in Philosophy from the University of Bologna. Lecturer on contract at IED Milano photography departement, she has exhibited her work in public institutions, private galleries and film festivals both in Italy and abroad.

Luigi Ghirri (1943 – 1992) was an extraordinary photographer as well as a prolific writer and curator, today considered as the most important Italian photographer of the 20th century. Questioning the codes of the medium, photography for Ghirri was a means of knowledge, a form of poetry, a way to relate to the world and a mental habitat where boundaries and territories intersect and fluctuate. His innovative work has become part of prestigious museum’s and private collections worldwide, and is still regularly presented to the public in solo and group exhibitions.