On the female body, fungi, and photography as contemporary augury

In Fruiting Bodies, Ying Ang removes the image from the realm of the ordinary to return it to its primal function: revelation. This is not about seeing, but about piercing through — slicing the undergrowth to listen for its breath. In this dissonant and hypnotic visual corpus, photography ceases to be a tool and becomes flesh — spongy, filamentous, radical. Like fungi. Like women who are no longer fertile, and thus, by the logics of capitalist patriarchy, no longer “useful.”

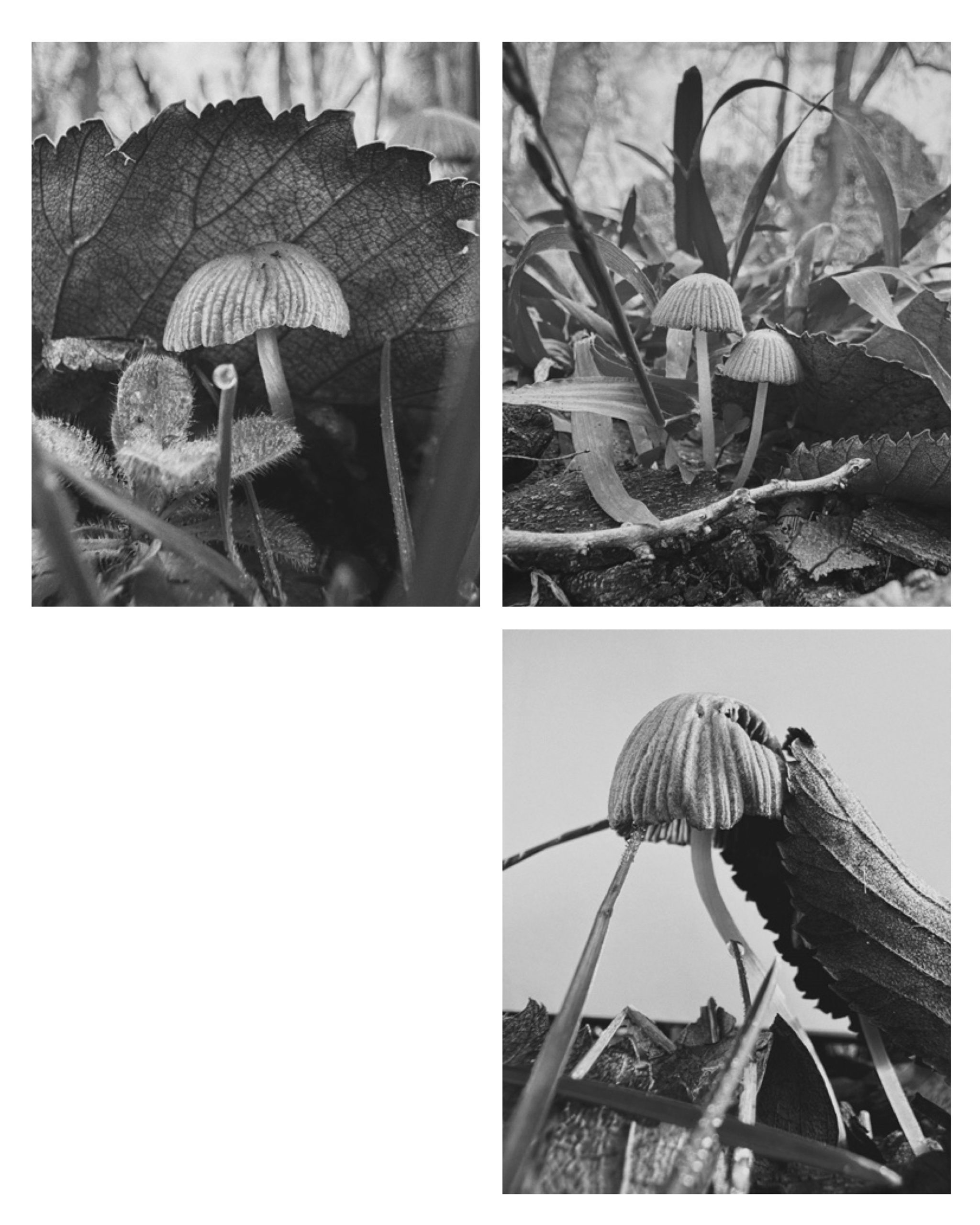

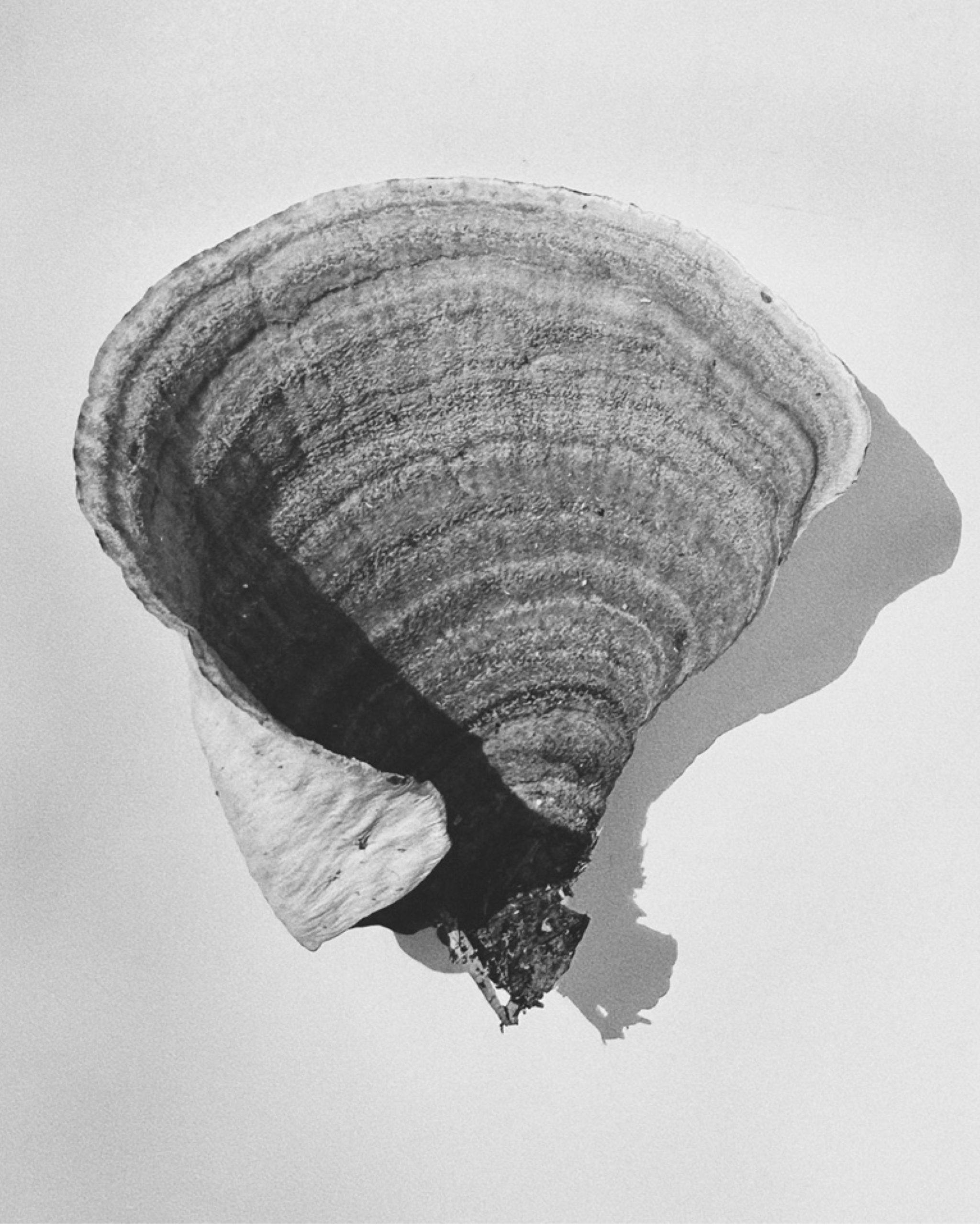

But Fruiting Bodies doesn’t stop at metaphor. It becomes a visual liturgy. Ang frames fungal bodies with the same sacred composure typically reserved for human portraiture. She photographs them in their excess — in saturated pigments, damp soils, acid greens, ferrous reds, and also in a black and white that is never neutral, but rather an etching, a residue, a resonance. Each image evokes a forgotten iconography — of cycles, of decay as threshold, of life regenerating through surrender.

Far from being a reductive analogy, the pairing of the mature fungus and the postmenopausal woman becomes an act of quiet defiance — and of poetry. The bodies in these portraits do not beg to be seen; they demand it. In doing so, they subvert the rhetoric of aging, which so often relegates older women to spectral versions of their younger selves. Instead, Ang places them at the center of a visual ritual that acknowledges their oracular power — their capacity to weave unseen networks, to nourish what remains unacknowledged by the dominant gaze.

Like mycelium — that intricate underground lattice of intelligence — older women here emerge as emblems of ancestral, embodied knowledge. A knowledge that is nonlinear, unwritten, transmitted in gesture, scent, and silence. One is reminded of Donna Haraway’s ecofeminist kinships, of her Chthulucene, where compost takes precedence over progress. Ang’s work aligns itself with such speculative lineages — not merely documenting life but redefining the taxonomy of the living.

There is, too, a rough sensuality in these images: split caps, glistening gills, soft and glutinous surfaces speak of an eroticism untethered from function or performance. A pleasure intrinsic to the body itself — its cellular memory, its quiet autopoiesis. Here, to “fruit” is not to mother but to exist, to appear, to unfold — stubbornly, gorgeously — outside the logic of productivity.

Fruiting Bodies is, above all, an act of reclamation. A reclamation of gaze — no longer phallic, fixed, extractive, but rhizomatic, diffused, porous. Ang teaches us that what grows on the margins, what ferments in decomposition, possesses a generative force that our performance-driven culture refuses to acknowledge.

In a time that sedates aging and sterilizes every discourse around the non-normative body, these fungal images become speculative relics, portals toward a new grammar of being. A grammar unafraid of rupture, that finds radiance in rot and knowledge in the skin that folds inward.

Ang does not invite contemplation — she demands repositioning. To become humid, permeable, susceptible to the infection of the real. In this way, her work is not merely aesthetic: it is ethical. It teaches coexistence, attentiveness, and trust in the forms that evade fast perception. A celebration of maturity not as an ending, but as intensification.

A late bloom — no longer asking for permission to be seen.

Buy Fruiting Bodies