There is a double tension in Arnaldo Pomodoro’s work: a form of research that unfolds as an excavation through time — between past and future, childhood and maturity — and translates into a sculptural language capable of generating space, not merely occupying it.

With Open Studio #4 – Places, Memories and Visions, the Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro (from October 4, 2025, to May 31, 2026) opens a new season of reflection on the artist’s oeuvre, transforming his studio in Via Vigevano into a living organism, where sculptures act as instruments of communication: ambivalent, at times warlike, always ready to decode or distort the signals of the world.

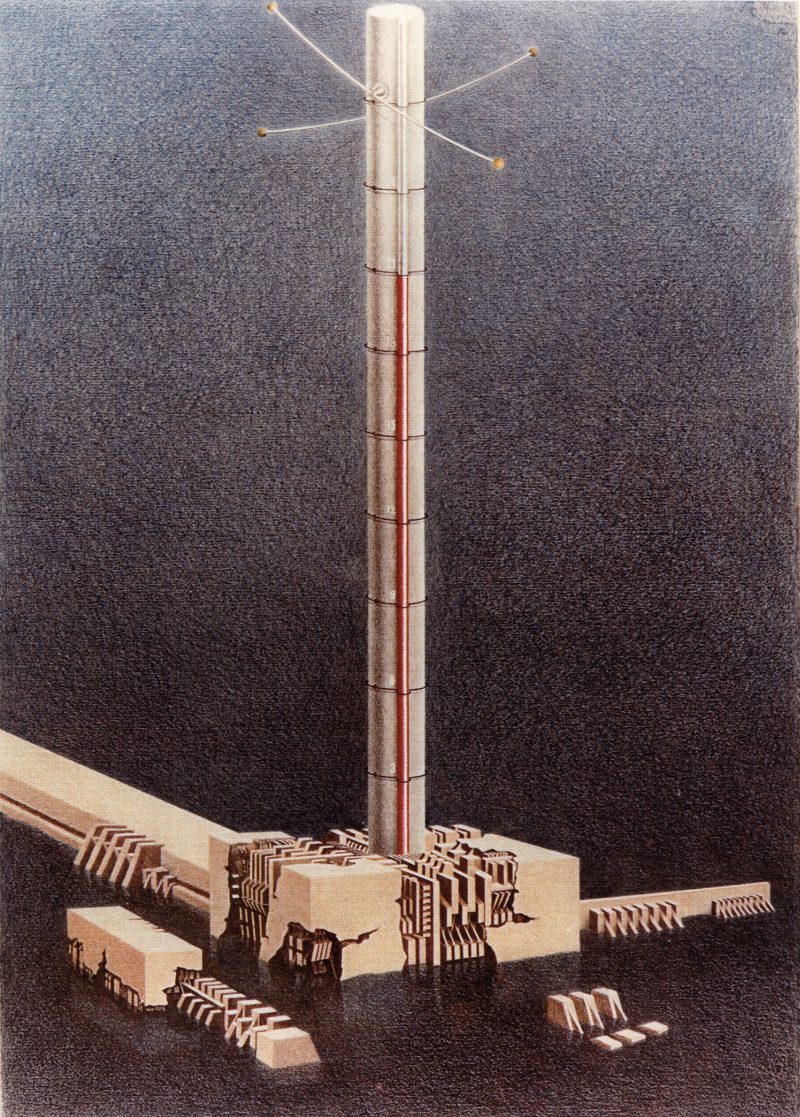

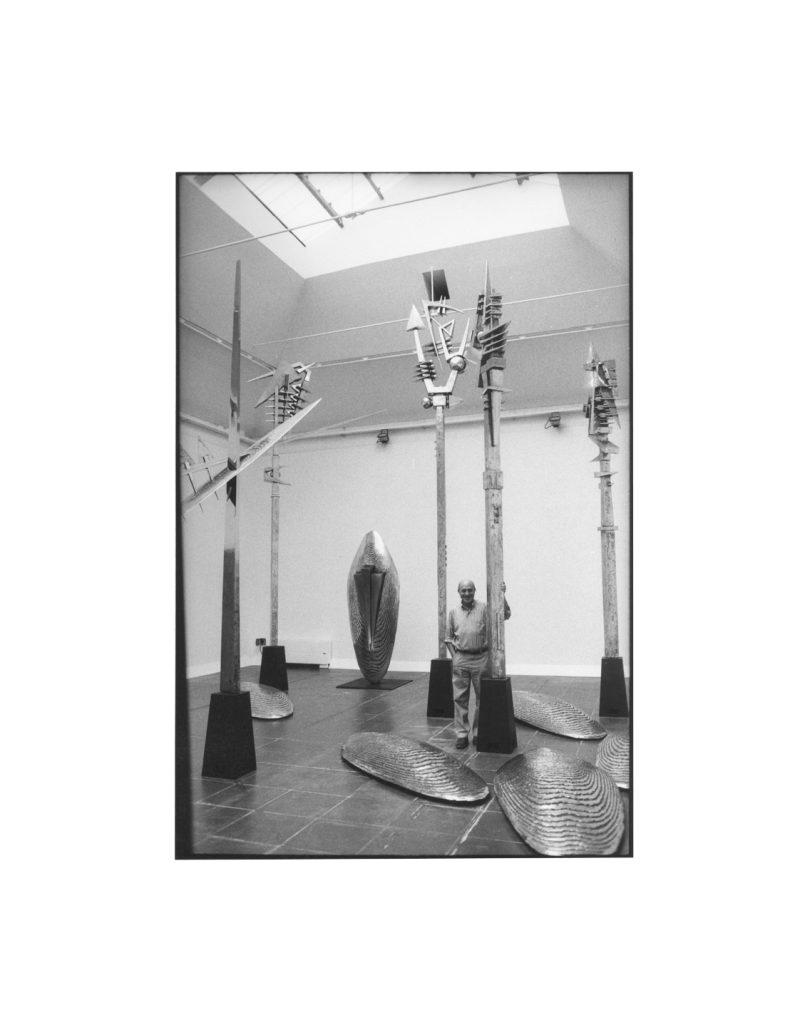

In the Salone, the works interact like fragments of ancient civilizations — Egypt, Babylon, Mesopotamia — sedimenting the memory of the sea and the earth in forms of bronze and matter. Here appear the Cippi (1983–1984), Scettri e Rive dei mari (1987–1988), Aste cielari (1978–1980) and Rotativa di Babilonia (1991): a kind of mythological machine, halfway between a weapon and a game, poised between the constructive power of civilization and its inevitable decay.

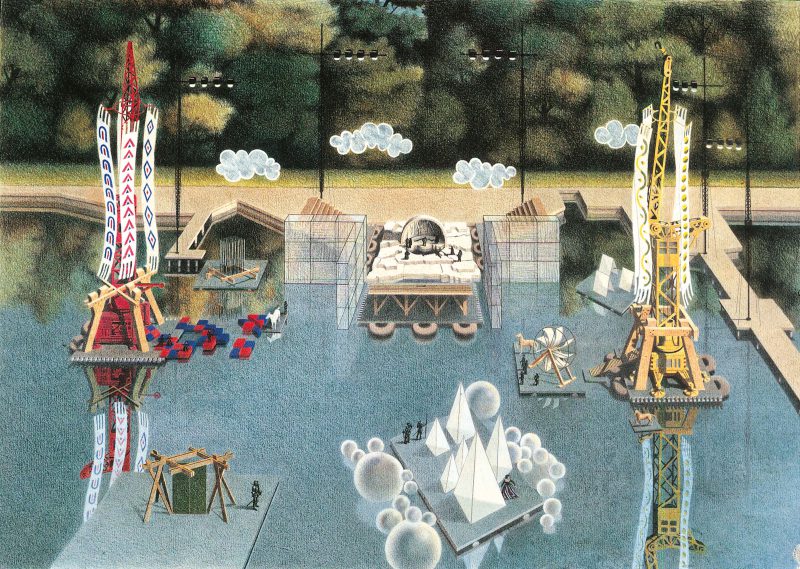

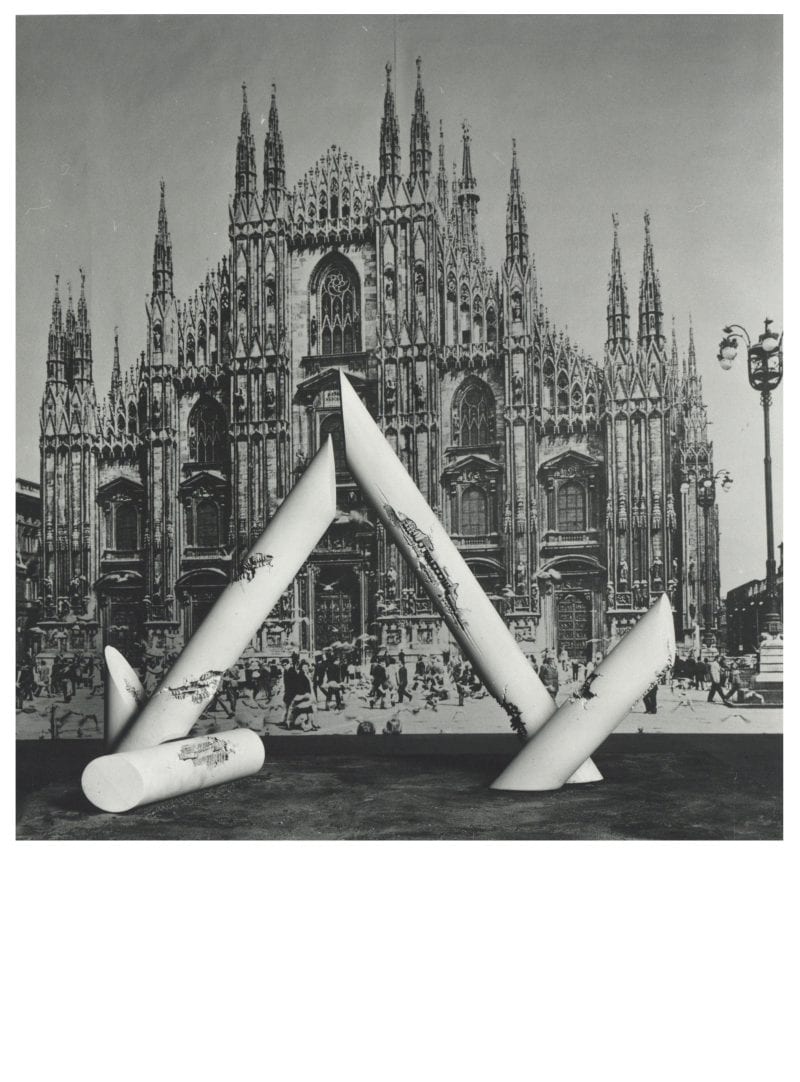

Pomodoro speaks of “exercises of invention,” of sculptures conceived to alter the very place in which they stand — a transition from sculpture as an object in a room to sculpture that becomes the room itself, a space to be traversed, an environment of passage. As in his celebrated installation at the 1988 Venice Biennale, with the Ossi di seppia spread along the sea, or in the Labyrinth at Via Solari, space becomes narrative, experience, living memory.

The antennas that rise from Pomodoro’s works — “a forest of antennas that are my own antennas of communication,” as he once said — become sensory extensions, tribal masks that capture and release signals from an interior Mediterranean. Among these forms, the viewer moves like through a mental landscape, a territory where memory and vision, reality and myth, are no longer distinct.

Within this path, a broader reflection emerges on the time of civilizations — a circular time in which the past does not disappear but persists, reactivated through matter. Sculpture, then, becomes rotary in the deepest sense of the term — like a press that imprints stories, a primordial communication tool that continues to generate signs.

In the Progettazione space, the Visionary Projects — from the New Cemetery of Urbino to The Pietrarubbia Group, and Tenda Fortilizio — reveal Pomodoro’s most utopian side: his drive to imagine total environments, ideal architectures where sculpture coincides with life itself. The journey concludes with the project Ingresso nel Labirinto (Entrance into the Labyrinth, 1995–2011), the environnement in which Pomodoro elaborates, on a grand scale, his lifelong themes of place, memory and vision.

Located beneath Via Solari 35 — the Milan headquarters of FENDI — the Labyrinth was reopened to the public on March 20, 2025, and can be visited only by reservation, through a guided tour lasting about 45 minutes. It is not a decorative maze, but rather a place that overturns the traditional notion of the labyrinth: a carved darkness, walls incised with signs that emerge like lost alphabets. The work draws inspiration from the Epic of Gilgamesh, transforming time into space and matter into writing — a journey between myth and memory that also reveals the inner workshop of Pomodoro’s language.

The reopening followed a restoration and renewal of the lighting design (curated by Lisa Marchesi Studio, with Viabizzuno fixtures and Casambi control systems), highlighting the reliefs, wedges, and perforations as the texture of an ancient language. In the atrium at Solari 35, two of Pomodoro’s costume sculptures — Didone (1986) and Creonte (1988) — are also on view, underlining the continuity between his theatrical practice and his conception of sculpture as a space to be traversed.

Pomodoro himself described artistic practice as a social duty:

“Leaving one’s studio is not a privilege, it’s a duty.”

In this sense, the Foundation carries forward his legacy — opening its spaces to visitors, workshops, children and adults who wish to “learn to see with their hands.”

In this fourth chapter of Open Studio, sculpture becomes language, and language becomes place: a space one can inhabit, built from metal bones and antennas of thought, where the ancient and the future touch in a continuous gesture of invention.