Caterina Barbieri explores themes of the phenomenology of perception and artificial intelligence in music through a minimalist aesthetic. Her work has been presented in international contexts such as Atonal, Sónar, Unsound, Mutek, Primavera Sound, the Barbican Centre, Philharmonie de Paris, the Venice Biennale, and Berghain. Her latest work, Ecstatic Computation (2019, Editions Mego), was designated album of the year by Bleep, receiving acclaim from international critics and being listed among the best albums in numerous charts.

I can’t remember how many handstands I used to do every day between the age of 7 and 9. I was obsessed with handstands and I did them all the time: in the classroom at school, in the park at break time and then back at my parent’s house in Bologna – first in the courtyard, then while going towards the stairs and then finally in my bedroom. My mum says that I spent most of my childhood upside-down. I just really enjoyed watching familiar landscapes lose that familiarity and become these alien scenes – radically distorted, tilted and twisted. I don’t remember how I learned but it was as natural as walking for me. I remember the magnetic sensation of finding balance mid-air. The heady feeling of gravity. I remember I was so impatient to do handstands that I would forget about everything else.

Ruben Spini is a multimedia artist and publisher. He engages in open research free from fixed formats on the themes of communicability and perception, particularly referring to religious traditions and information theory. He is the editor of Ultravioletto, a recently founded publishing company dedicated to forms of interdisciplinary experimental writing that go beyond the rigid confines of the publishing market.

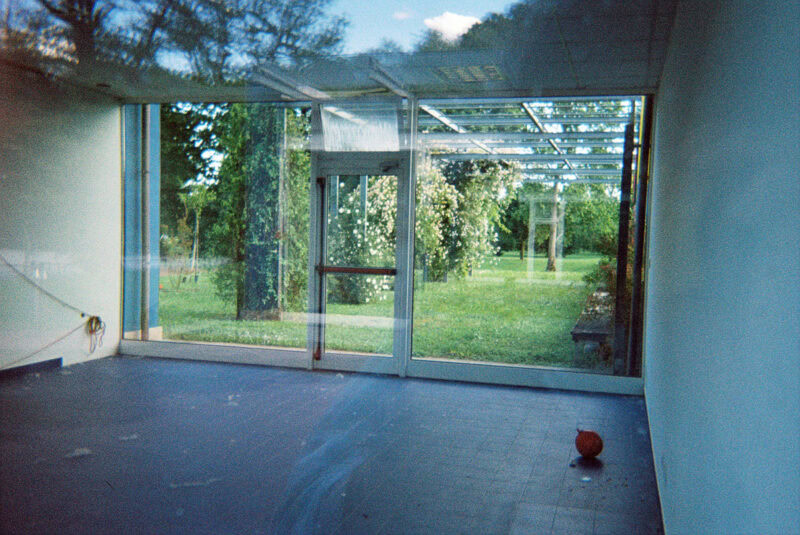

I have a conflictual relationship with the production of images. When I was younger my reality mostly expanded through my immagination: I existed in the rooms of my home and the gardens of my village, but also in scenes from books or videogames with the very same intensity, presence and interaction. This way of being became my profession. I know a different place, and I know how to brig it alive, so much so that I can access it and other can too. But when we are children, vision have the fleeting duration granted to them by desire. Some naturally die and decompose to fertilise future growth according to hidden yet no less real mechanism. Even now I can’t explain the logic: some places disappeared and others took their place and this process was growing up. And I was complicit in this phenomenon, even in the amnesia, the forgetfulness. I have the impression that today, as adults, we have betrayed this complicity: all we want is to expand and protect our memory. There is no technological equivalent for the opposite, for oblivion. And herein lies the conflict that I feel: I can create, show and remember new things but how can I forget? And without forgetting, is creative activity not just hoarding? Fires are often a natural part of a biome’s life cycle. The forest is finally thinned out and new light can reach the undergrowth in spring, bringing with it new growth. New trees and even flowers sprout among the charred branches. I refuse to hoard my visions but I struggle to find the spiritual equivalent to that fire. If it exists, it must be an introverted process, in a certain sense. I think often of Rilke’s words: «The work of the eyes is done. Go now and do the heart work on the images imprisoned within you». In sixteenth century Italy, much literary production was dedicated to mnemotechnics or the expansion of memory by using games, mental images and technology. Part of the work was often devoted to forgetting, De Oblivion, as it appeared quite obvious to the intellectuals of the time that there was a limit to the accumulation of knowledge and that forgetting was as important as learning. The alternative was to share the fate of the man who suffered from heartache, «the amorous phantasma […] intent on occupying, indeed devouring, the space of imagination and memory». Through introspection, it was possible to release certain memories in order to protect others and allow new ones in. «To open a window onto the heart thus means constructing, perhaps artificially, an observatory onto the phantasmata that inhabit the body and the psyche […] we can think of the window onto the heart as an observation point that allows one to see the inside of a gallery in which paintings and sculptures make feelings and thoughts visible» (Lina Bolzoni, The Gallery of Memory: Literary and Iconographic Models in the Age of the Printing Press). The analogy is similar to Rilke’s advice and diametrically opposed to the conception we have of memory today, a roll of equivalent images that can be archived without limit. Doing heart work means recovering that childish complicity with our visions and memories, opening a window on to our heart and turning it into an amora obscura that allows goodbyes, and therefore growth.