Let’s talk about privilege. The crucial problem with privilege is that people who have it, to any degree, usually don’t see it. Being a white-cisgender-heterosexual-male feels like a given, if you are a white cisgender heterosexual male. And the situation is even more complicated given that most people who have the power and platform to express their views to a wide audience belong to this “category”. Privileged individuals should change their habits – even small changes can have a positive impact – and take into consideration that those small acts might be the missing piece in a far bigger puzzle. People should be aware when addressing others, starting by not assuming anyone’s gender or sexual orientation. Homosexuality today is still in some ways perceived as a “deviation” from what is deemed the “most normal” sexual orientation.

Even if the world had no homo-bi-trans- phobes in it, there would still be a lot to do to make it inclusive for everybody. Inclusiveness is not just about making sure that everybody feels ok with who they are, but about building a world where it is easy for everybody to understand who they are or who they want to be. These barriers are still widely present, with varying degrees of severity, but the world of sport seems to be an area that is very behind on inclusiveness, across every country.

Football can be considered as more of a culture than a mere sport. Cultures bring with them values, ideas and concepts that are all too often blindly accepted, regardless of their nature. In the world of sports, there is a widely held idea of how a man should look and behave, and this “idea” is particularly rooted in football. Football and “masculinity” are linked in such a strong and pervasive way that people even think female players are “less feminine” and make assumptions about their sexual orientation. Theory is easy when separated from practical application. Real experiences are much more complex. It is so much easier to relate to the world along the lines of commonly held ideas because that relieves us of the need to take the complexity of human relationships into account. It is paramount though to be aware that not everybody is a privileged white-cisgender-het- erosexual-male, and that those “commonly held ideas” might actually be harmful and painful for others. From a statistical point of view, it is reasonable to believe that there are far more homosexual players in the world of football than we know about. Some heterosexual team members might think it weird to have a homosexual teammate, and all of a sudden, a general atmosphere builds up where a gay player would definitely think twice before coming out. This much feared weirdness is most likely linked to the misbelief that sexual tensions would arise within the team. The idea that every heterosexual cisgender men is sexually attracted to every female is pure nonsense, and the same stands when we’re discussing homosexuality. Attraction aside, there is another big topic that often people seem to forget: consent. Whatever a person’s sexual orientation and gender, all relationships are consensual, or at least they should be (if your relationship is not, that is a criminal matter that must be investigated, regardless of the topics covered in this paper). Hopefully, even those who firmly believe in these preconceptions would change their mind if they saw first-hand that someone’s sexual orientation does not change anyone’s experience in any given situation, even when sharing a locker room with a teammate of the same gender but of a different sexual orientation. All bad behaviour must be condemned but, in my opinion, many things would improve organically if people started to recognise their privileged positions and acknowledge that not everybody benefits from such an advantage. To narrow it down, not every white male is heterosexual, and yet homosexuality still seems to be widely perceived as an unpleasant surprise. Being homosexual should not be considered a problem or obstacle in general, especially in the world of football. Homosexuality is important, just as any sexual orientation is since it’s a big part of who people are, but it is only when all of this makes no difference that everything will be completely different.

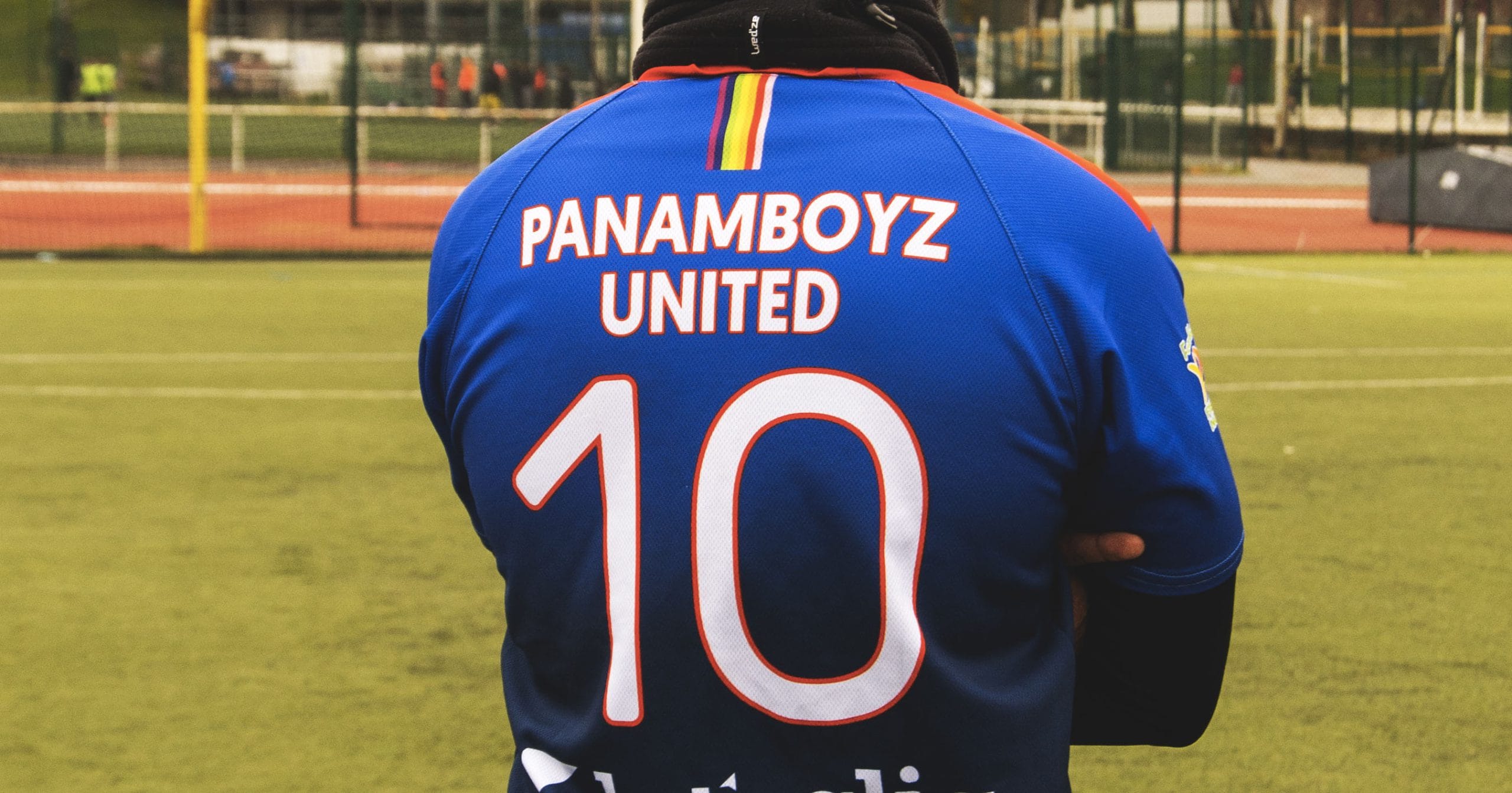

Let’s start with a fairly easy but relevant question, can you list all the sexual orientations, genders, ethnicities and religions that PanamBoyz & Girlz United currently represents on the team? Not just the players but the whole Panam family.

The truth is that we don’t know. The whole point of our club is to provide a safe space where everybody can play football. We talk about sexual orientation very openly, as well as other facets of identity, but we don’t ask or run statistics.

From your perspective, how do you feel that discrimination plays out in football? Is there any particular experience that drove you to start PanamBoyz & Girlz United?

Football is the most universal sport, but it remains in many aspects far removed from the universal values it should promote. The first objective of our club is to provide a safe and inclusive space for everybody to play football. But our goal is also to act, engage and dialogue with all the stakeholders in the football world, in order to drive change, evolve mindsets and create a more inclusive environment at all levels of football, both professional and amateur. Regarding the specific question about sexual orientation, it is undeniable that homosexuality is a taboo in the football world. The fact that no professional football player has come out says it all.

What do you think fans and people outside the organisational circle of football could do to help make a difference on a wider level? (e.g., chanting, TV shows, social media tone of voice, etc.)

The issue of discrimination in general and homophobia in particular in football is systemic and will take time and effort from all parties to improve. The fact that it is considered acceptable to hear homophobic chants in stadiums and that some football representatives consider it a part of football folklore is a massive issue. It treats the issue of homophobia as minor or just a “normal” reflection of what happens in our society, only amplified due to the stadium context. But the truth is, it is not. While society has evolved, it seems that the football world and associated culture is still stuck decades behind. Stuck in this “”macho and “virile” culture, where sometimes humiliating the adversary becomes more important than winning.

Have you ever been asked about how the locker room experience is different in a team of mixed sexual orientation? Are these questions relevant?

Journalists often ask this question but it is of no relevance whatsoever. If you are imagining sex in the locker room then you clearly have never worked out. There is no less-gendered place than a football locker room. This question therefore makes no sense. Our locker room sees shouts of joy after a victory and cries of distress or anger after a loss, along with jokes, camaraderie, and nothing more.

Football is more of a culture than a mere sport. Why is this the case with football? What’s the difference compared to other sports?

Well, all this is hard to understand and analyse. Because there are so many great things in football culture, in its ability to bond people, to convey the best emotions, beyond origins and social background. But it can also bring out the worst in people, their hatred and violence. Why is there this desire to crush and humiliate the adversary (and therefore insult them) to an extent that you probably don’t see in other sports? Hard to say. And why is this macho virile culture so uncontrolled and glorified? Again, hard to say, but this is something that needs to change for sure if football wants to keep attracting young people. Making football more inclusive is a win-win for everybody: clubs, supporters and sponsors alike. As the most played sport in the world, football needs to uphold its social responsibility and assume the role of social sounding board in a positive way. Now is the time. I mean, come on, the French rugby federation is now talking about including transgender players in rugby teams, they are 30 years ahead compared to football!

Do you consider what PanamBoyz & Girlz United does as activism?

We are not just a football club, we are an activist football club and we own that: since we were founded in 2013, we have carried out extensive work, far away from the glory of the match highlights, to convince the professional football league (LFP) to take action against homophobia. And it has paid off! In 2014 and 2016, we succeeded in getting Arc en Ciel players to wear Arc en Ciel laces. In 2019, Arc en Ciel armbands for captains and coaches. And last May, we succeeded in getting all professional Ligue 1 and League 2 players to play with Arc en Ciel flocked jerseys and to participate in a campaign entitled Gay or straight, we all wear the same jersey. This is a first for France and continental Europe. So, yes, we are an activist club. We also meet supporters and professional players in the making to explain things to them and attempt to help them evolve their vocabulary, language and attitudes. To help them understand that a homosexual player is a player like any other. We take pride in our work.

Has your position of inclusiveness ever been labelled as a “well-planned marketing strategy”? If so, how did you (or would you) reply?

We are a not-for-profit club, so marketing is not really our thing… What we offer is a safe space (and nice people) for playing football.

What’s your position on mixed gender football championships from a “sport” perspective? Do physical attributes and strengths make a difference when it comes to mixed championships?

We believe there should be more opportunity to play mixed gender. Unfortunately, there are only a few, usually during tournaments. We currently train together when we can but we play in different championships, which are not mixed gender. We can’t lie, mixing boys and girls isn’t always easy. But that has more to do with the fact that there are more beginners in our female team than in our male team, rather than what could be seen as sexism. In terms of physical attributes and so on, let’s make something clear. The main difference is the fact that it is still very very hard for little girls to play football at school or in clubs. If you don’t get to play or you feel rejected or not “legitimate” in playing football, well, then you won’t play or you won’t progress as fast. Our female team is currently running a project to promote football among young girls in our neighbourhood and to empower them to use free-access football pitches. What is hard to believe is that young girls today still find themselves in the exact same situation that some of our Girlz experienced 20 years ago! It is still very hard for a young girl to find a space in which to play football and for her to feel at ease on a football pitch! Again, what a shame for the football world because this excludes half of the world’s population from a sport that should help people to bond and convey universal values of inclusiveness.

How much time do you think is still needed before we get to a point when nobody will even care about sexual orientation in football? Which milestones do we still have to achieve to get to that point?

Probably a few decades, but we are reaching some tipping points. The fact that several football players participated in a video against homophobia in France for the first time this year is, in our view, something that wouldn’t have been conceivable a few years ago. Some former football players have also started talking, recently a very moving testimony from Ouissem Belgacem explaining how homophobia crushed his starting career was received very positively from most of the football world and the media. Everything is now ready for a big football player to come out of the closet. And the more talented and successful he is, the most impact it will have, although it will be difficult. What is absolutely crucial is also to train football coaches, because they are the ones who have the biggest impact on the mindsets and behaviour of young players. Raising awareness against discrimination and promoting inclusivity should be part of the coaching curriculum. Unfortunately, that is far from being the case today.

Credits

Words by Alessandro De Agostini

Photography by Sekou Camara

Starring Bertrand Lambert