After one of those days where you’re so tired that you can no longer tell whether the spontaneous smile spreading across your face is a sign of joy or hysteria, your sole desire is to suffocate your thoughts with a soft pillow, preferably one with a new pillowcase that smells like fresh laundry, letting yourself be whisked away by enchanting dreams. Of course, it’s usually the opposite. The more tired we are, the less we can sleep; the more exhausted, the lumpier and scratchier the pillow seems. One moment before, your vision was blurred and your eyes half-closed as though tiny little weights dangled from your lashes but as soon as the light goes out, those weights are replaced with sharp toothpicks, propping your eyelids open like two cracks onto a world that shows no sign of fading. Beds, or rather our beds in the dark, are the ideal environment for thoughts to float to the surface. Like cats, bats and leopards, thoughts are nocturnal animals that hunt their prey – us and our peace of mind – once dark has fallen all around us. And with this premise, which might have made us seem a little unstable, we can tell you with certainty that some people have never stopped asking why.

For some people, the notorious “why phase” that starts around the age of three or four never comes to an end, it is merely the interlocutor that changes. No longer our family but ourselves. A British study has shown that children ask their parents 288 questions a day, an average of 23 per hour. Well, later in life, those 288 questions start to emerge in the evening, tormenting us for answers until sleep finally gets the best of our prone bodies. Why do you hear the sea in shells? Why don’t we dream all the time? Why aren’t women as strong as men? Why is the sea salty? Why is yawning contagious? We could go on for hours. There isn’t always an answer but you’ve got to give the imagination free rein to explain things, correctly or not, and interpret these questions from our own personal perspective on the world. Curiosity inevitably gets the better of us, of course, and the Googling can be almost schizophrenic the next morning but it is important to be able to answer our own questions if we are to judge our capacity for self-interpretation.

It is curiosity that underlies everything. Curiosity is the keyword but it’s a key that some people seem to have lost. The strangest aspect of the word “curiosity” is the fact that it comes from the Latin word cura, meaning care or concern. A curious person is, first and foremost, someone who cares about something. We take care of ourselves by feeding our souls with questions, we must be able to surprise ourselves and to find something that makes our hearts leap in every single moment. We get sucked in by false pixelated images every day, which is why we deserve some self-care. And by care, I mean unleashing the desire to know, a simple love of knowledge. Einstein said: «The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existence. One cannot help but be in awe when he contemplates the mysteries of eternity, of life, of the marvellous structure of reality. It is enough if one tries merely to comprehend a little of this mystery each day. Never lose a holy curiosity». We have this psychotic urge to grow up, unaware that the purity and naivety of childhood is the key to seeing the world through a different lens. With a devastating curiosity as though each day were our first. Growing up sucks, and not only because it means taking on more responsibility and watching our carefree freedom fly out the window, but also because heavy curtains are drawn over our eyes, making only the rational and “right” parts of the world visible. But the world is neither rational nor right, it is a mine of amazing thing that we simply must know. Only then will we be truly rich inside, luxuriating in a knowledge that only those who draw those heavy curtains can possess. Stephen Hawking said: «Remember to look up at the stars and not down at your feet. Try to make sense of what you see and wonder about what makes the universe exist. Be curious». We must be curious and ask ourselves why, always. We cannot live a full life without putting ourselves on the line.

New generations, overloaded with technology and advertising, have stopped asking why because it’s so very easy to find an answer, all it takes is a quick whirl of the mouse. Or perhaps they stopped because they aren’t interested in finding the answer to their queries, preferring to remain in familiar ignorance. There is no curiosity, just haste and a need to know things as soon as possible. But some of us are still part of that generation that narrowly escaped, and thank goodness I should add, the tyranny of technology. We belong to the generation that still needs to ask: why? Just like children.

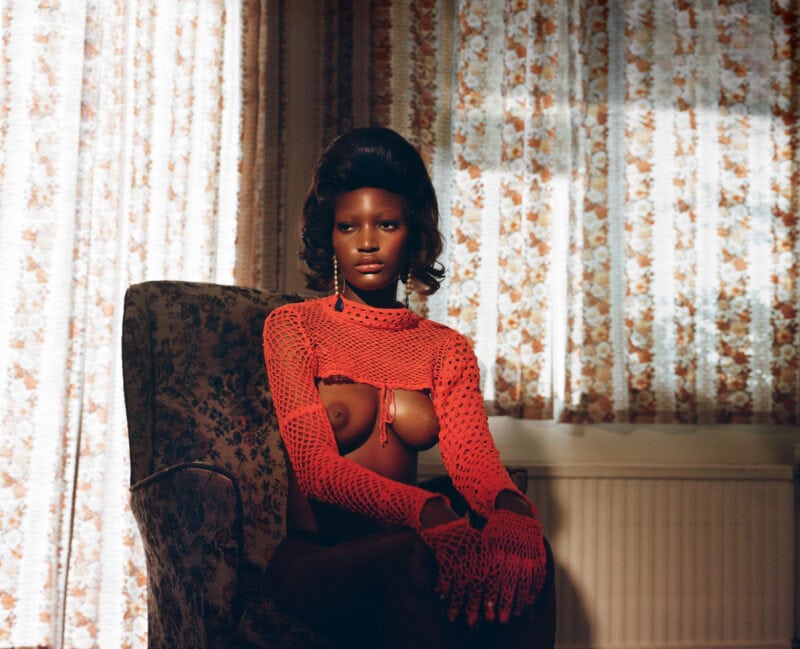

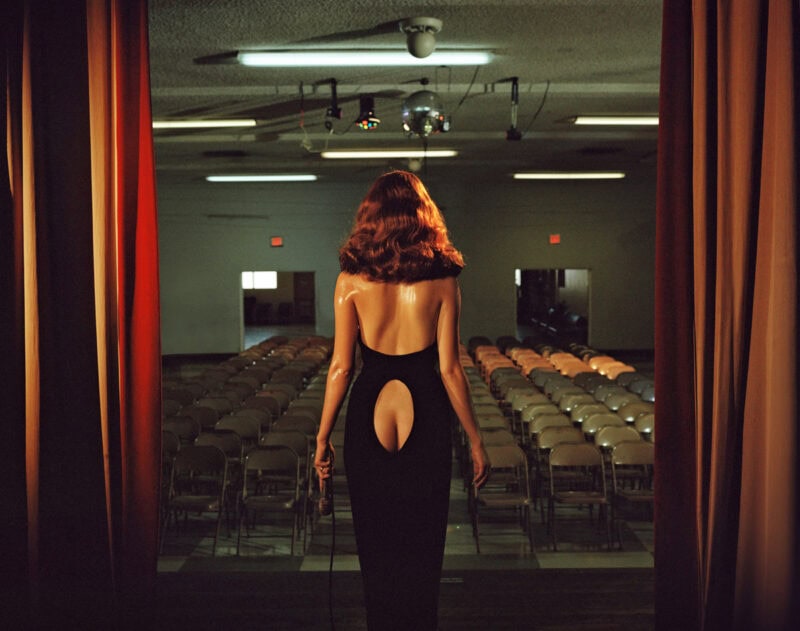

My encounter with Nadia Lee Cohen, far from giving me calmer and emptier dreams, merely increased my curiosity, raising new questions and queries within me which I try to answer in the dead of night. When the only sound is my thoughts bumping into each other as they try to find a definitive answer which, between you and me, I don’t think exists. Why women? Why now? I believe this is the most frequently reoccurring question and the one responsible for the most sleepless nights. I grew up in a female-dominated family and yet some “female” issues are still foreign to me. It was Nadia’s arrival that opened my eyes to certain topics. Beauty, modesty, love for our bodies and the ability to love ourselves without judging too harshly. The freedom to show one’s body without hesitation and the battle against a prejudiced and judgemental society. We must hang up our judgement to welcome the “other”. Whether male or female, young or old, I think that we all have to face our own “whys”. I am certain that it is wrong to divide these questions by gender when, as equal conscious beings, we all torment ourselves at night, in the darkness of our room, with the sole hope that our train of thought might soon come to a stop and rest for a moment before starting to ask all over again: why?

Your name precedes even your photographs. You give us a glimpse of the old Los Angeles that we only see in films. Why is Nadia Lee Cohen the talk of the town? What do the characters you portray have that you don’t?

Haha, is she? I haven’t heard of her… Better hair? I’m not sure really… The characters are of course formed as a part of my own imagination, observations and inspirations – which means they probably have everything I don’t otherwise I wouldn’t be interested in photographing them.

Now that we know the reason for your fame, can you tell us why you chose women? What is the message behind your images?

I have always had an acute appreciation of femininity and was drawn to anyone who pushed it to theatrical limits. Camp, melodrama and dressing up are all deeply rooted within me and I see them constantly reappearing in the work as it progresses. I am constantly asked what the message is and it really is more fun not to answer. I find that when people contextualise their work too much it loses the magic and appeal – plus it’s a bit pretentious, isn’t it?

Do you consider yourself a feminist? Why?

Yes absolutely, I think people extract this from the work as it is female dominant, and they would be right to a certain extent. However, I am not overtly trying to inflict messages or opinions, those are to be extracted subjectively. The worlds are staged fiction, though the situations and characters are based on truth and real life. I am not moved by the concept of the magical or fantastical, I look instead to reality, mundanity, and everyday honesty and think this naturally shows in the photographs.

As a woman, what do you think about contemporary ideals of perfection related to femininity?

We are seeing more and more images each day that liberate and push back at the certain type of “perfection” that we have been accustomed to. For me personally, the art and cinema that I am drawn to tend to feature strong characters most of whom “imperfection” prevails over “perfection”. This concept has always greatly inspired my own work and it is gratifying to see this spreading more widely.

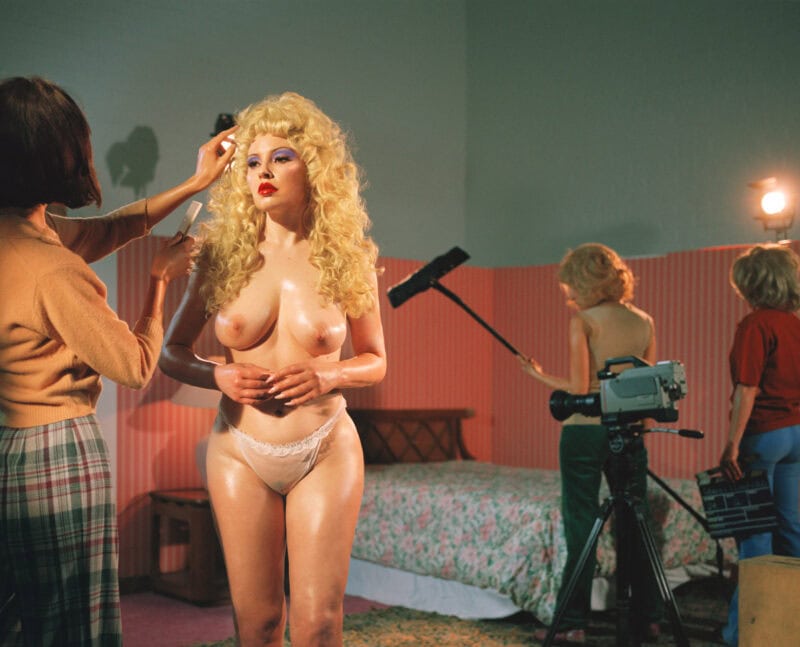

As the famous Andy Warhol said «I love Los Angeles, and I love Hollywood. They’re beautiful. Everybody’s plastic, but I love plastic. I want to be plastic». Your work is studded with unusual beauty standards: from the faces and make-up to the shapes of women who simulate extreme plastic surgery. Is this way of depicting women also meant to be a provocation with regard to how the canon of female beauty is evolving? Is there any socio-political meaning in your images?

I agree with Andy. There’s an artifice about Los Angeles that is pure magic. The subjects in my work are just depictions of people and characters that I find interesting and that I’m naturally drawn towards. Sometimes they are melodramatic, maybe even camp, they are always theatrical which means they evoke many forms of emotion, which is, of course, entirely subjective – I am not endeavouring to inflict specific emotions on the viewer but grateful if any are stirred.

What is your first memory of beauty?

Julie Bullard. My babysitter from when I was about 5. She had this mass of curly golden hair that I couldn’t fathom actually grew out of her head (it didn’t, she bleached and permed it). I think she was the first blonde person I saw in real life. She probably wasn’t even that good looking.

The perception of the female body has changed recently, as have beauty codes. Do you have any codes? What are your thoughts on the direction this is moving in?

You know, it really is odd that it hasn’t happened sooner, you’d think companies would want to sell things to more people, not just thin, white western models. I love unusual and unconventional beauty, to me it’s just more interesting to look at. We are exposed to so much censorship and so many rules that I find any rebellion against this notion feels refreshing. I also believe it is important for us to be exposed to varying body shapes in order to feel connected to our own.

Beauty canons are often distorted by social media, creating a fictitious and almost deceptive window onto reality. What is your relationship with selfies and Instagram?

Social media is fiction, and hopefully we will all realise that at some point. It’s a person’s own personally curated narrative and a window into the way they see themselves without any interruption. It’s actually very Warhol – I’m sure he would have loved it. People may view it as deceptive, but that’s probably because they aren’t getting any likes.

Do you ever wonder why things happen? What are your most persistent whys?

Has anyone answered no to that question? If so, they are probably lying. Most persistent whys in actual order:

Why is this taking so long?

Why can’t we teleport yet?

Why do I not feel like an adult?

Why isn’t my hair doing what I want it to?

Why asking why?

I once read about a man that answered the philosophy exam question «why?» just with «because», but he sounds like a bit of an arsehole.

Credits:

Words by Alice De Santis

Photography by Nadia Lee Cohen