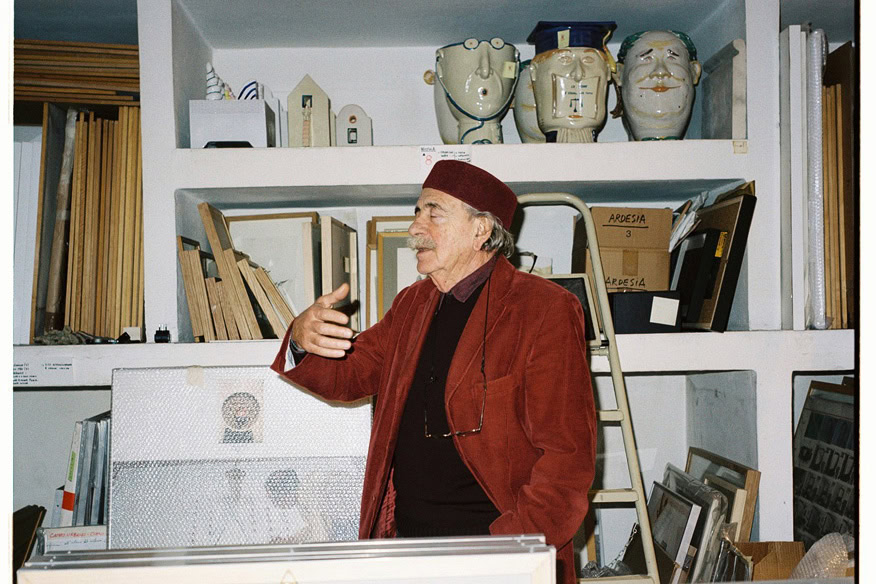

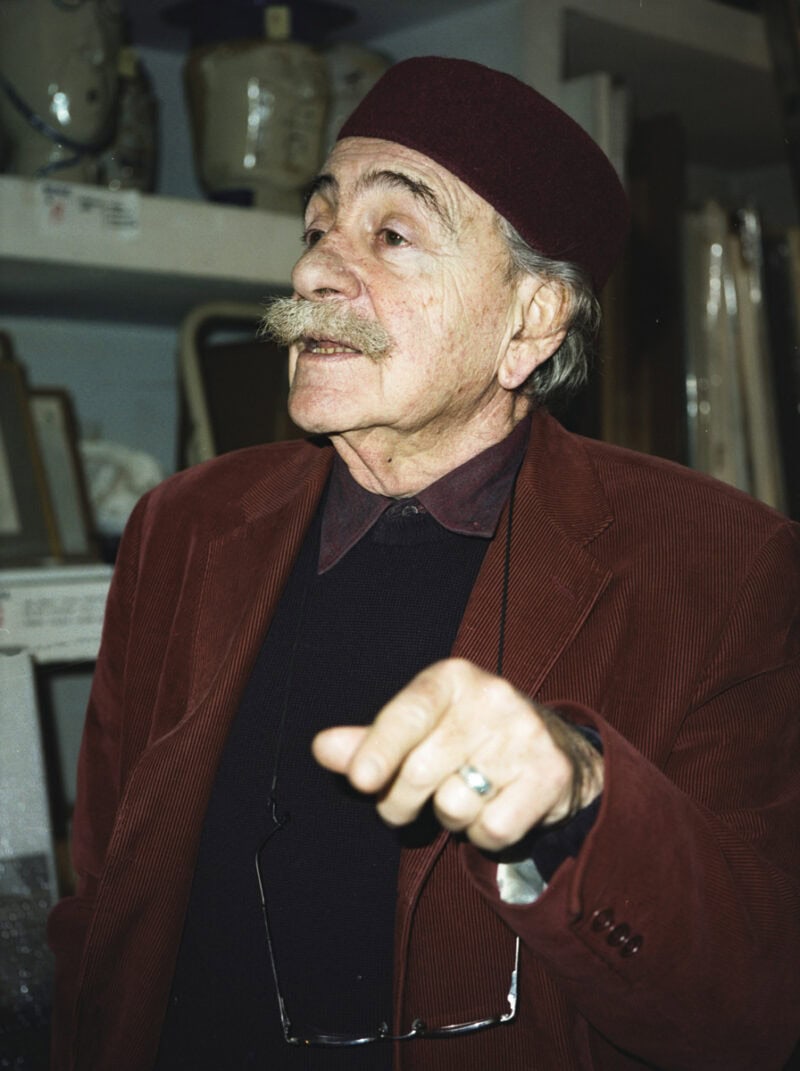

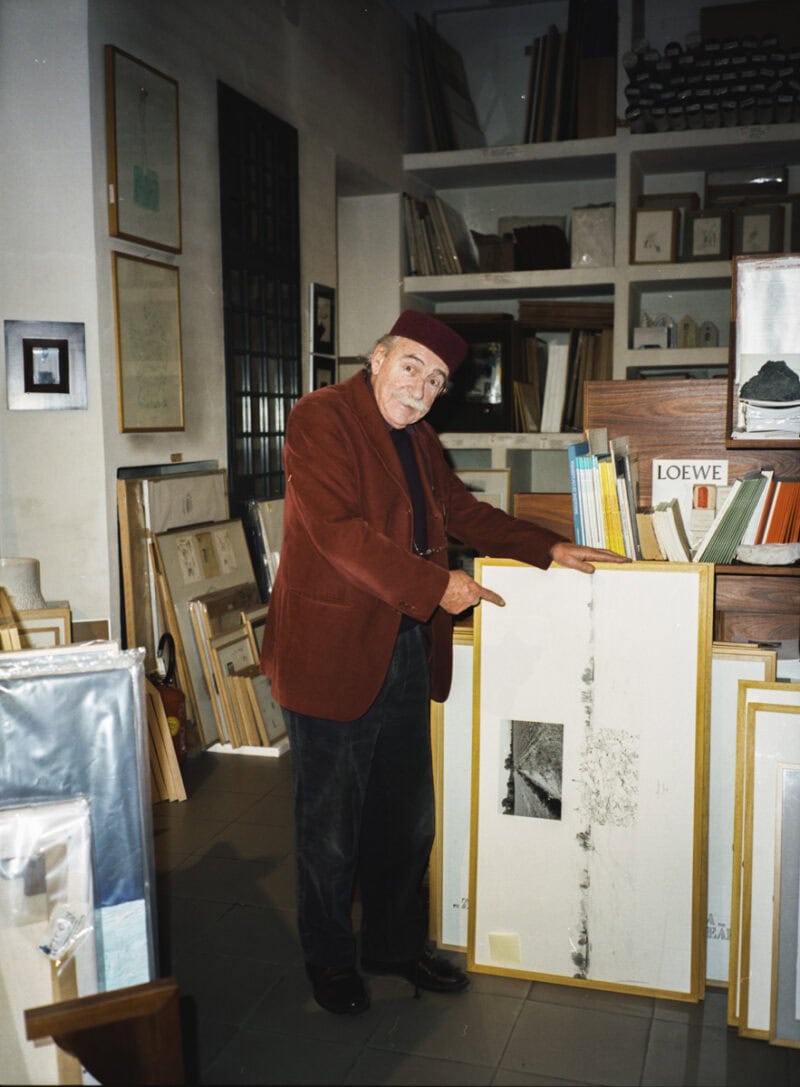

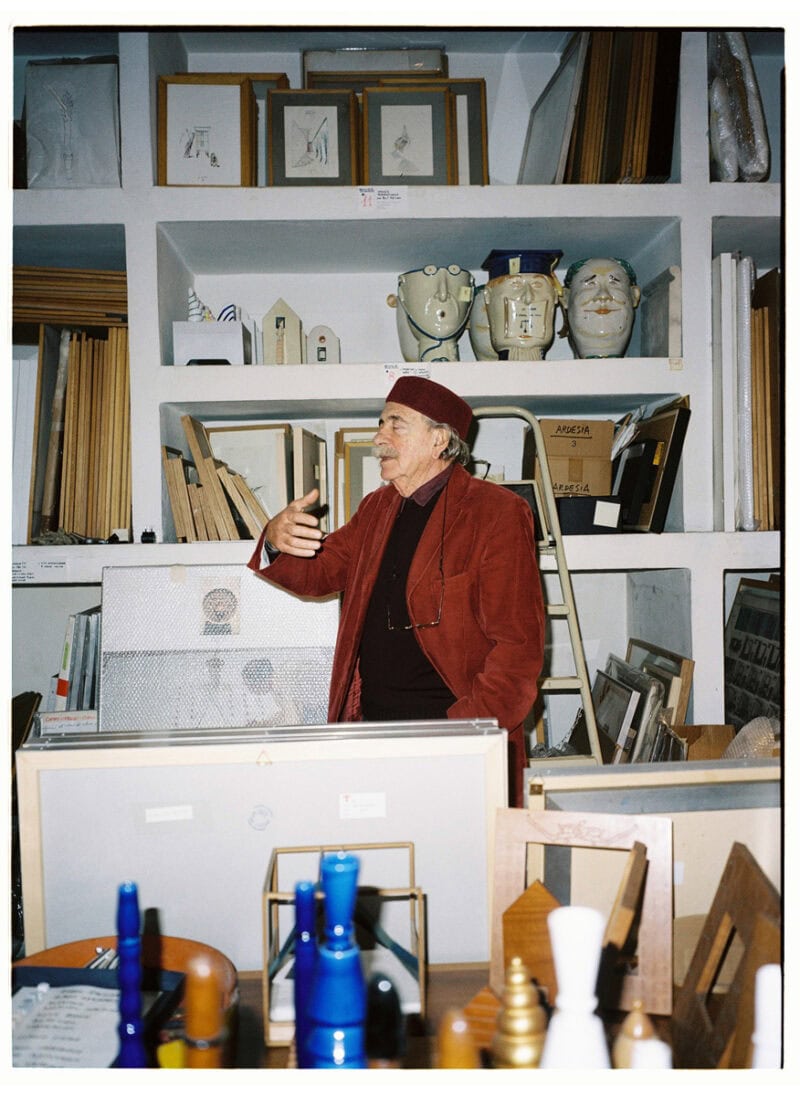

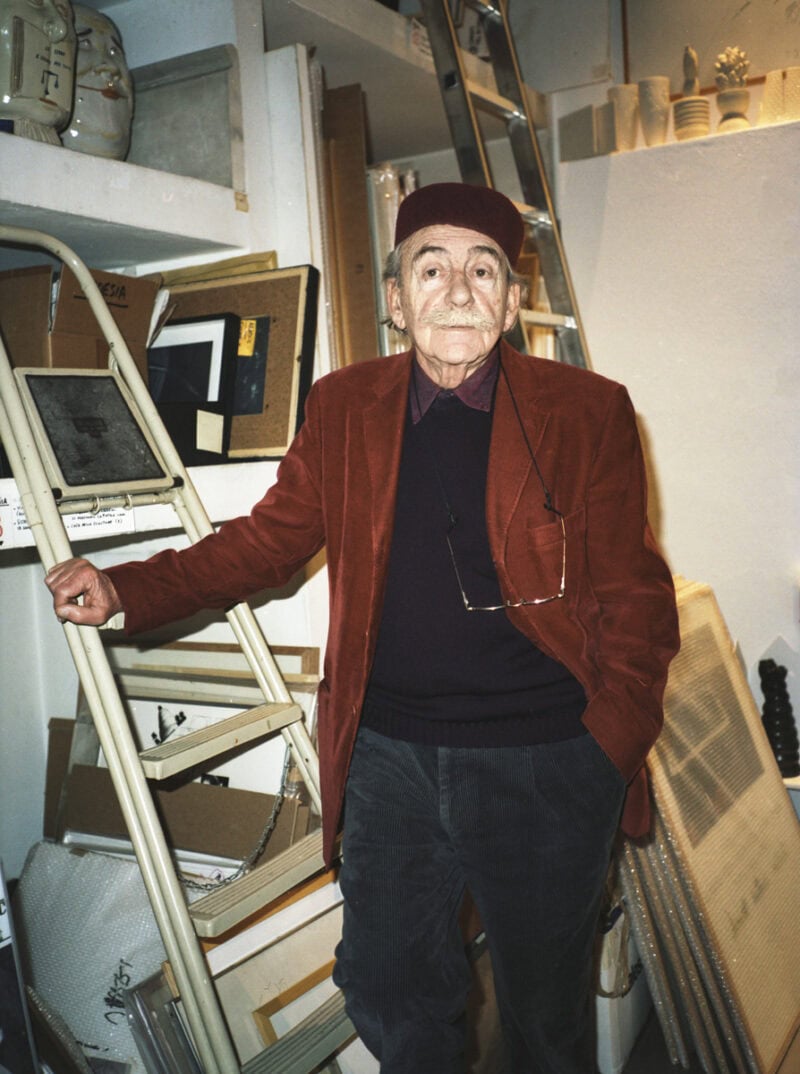

My gaze is immediately swept away whenever I enter Ugo La Pietra’s studio. Every time that I descend those stairs, I see the Amore Mediterraneo ceramics and I wonder when they came about, just as I do with everything else that has invaded the studio layer by layer: books, ceramics, magazines, collages, furniture and sculptures. The etymological meaning behind the Italian verb “to design” is simply “to throw forward”. Ugo la Pietra has always thrown forward for mankind and the experience and relationships that mankind enjoys in urban and public spaces. He does not build spaces, rather he designs places and creates imagery from daily life. He dreams by drawing, sees by photographing and walks by counting. But more than anything else, he has defined an approach that always prioritises life over the project itself. Ugo la Pietra reflects on the future by living in the present. Many people would call him a pioneer; I hope this interview will show that he is a genius.

Which elements within the urban space are fundamental for a city to feel welcoming?

For many years I have theorised that a city, in order to become such, must achieve what is called the “urban effect”. The urban effect stems from a series of different elements that range from traffic to culture, from information to moments of decompression (such as entertainment and leisure). When all these elements are present, you have a city. Cities can very often be homogeneous (in Japan, for example), configured as large monocultural settlements that only sell electronic equipment, for example, or where the local economy is entirely based on entertainment. When the situation is this heavily restricted to a single category and areas are heavily monopolised by a single component, the location cannot yet be called a city – as is the case in Milan’s Chinatown, where all the shops are wholesale and there is nothing else on offer. However, when all elements are present and co-participate, this creates the so-called urban effect and we can say that we are looking at a city. Of course, for a city to function, all these elements must be correctly proportioned, so that no element is in any way concealed, hidden, or even eliminated. For example, if a city’s urban effect is over-proportionally achieved by traffic or commerce but the fundamental components of decompression are missing (i.e. places with lower levels of crowding and noise), then we have a problem.

The underlying principles are the same as any natural phenomenon. In a forest, for example, many elements coexist. These include trees and bushes, of course, but equally grass and flowers. These components are all part of a single overall phenomenon. This overall phenomenon is made up of many elements which must exist in harmony. That is why many authors – especially artists – adopt critical attitudes towards the urban. One of the things revealed in their work is the exaggerated presence of the commercial system at the expense of culture. Or perhaps the exaggerated presence of traffic and a complete lack of information. All these components should be present yet often this is not the case. Why not?

Let’s imagine that I am a ninety-year-old woman and I want to go from my home to Ugo, meaning I have to traverse the public space…

Poor woman…

…which elements should I expect to come across on my journey?

Well, in order to survive – which doesn’t necessarily mean being happy…

Is survival different to living?

Of course. Living is a standard far above survival and it means achieving results, such as living somewhere that represents us, a place that we have modified in some way. Your personality dilates in your own home while this is not the case in a hotel room.

Mere survival, i.e. good use of space (which is different from liveability) requires at least three fundamentals: access to water, the means to go to the toilet and the means to rest. If an individual is unable to perform these three actions, they will have serious survival problems.

And this does not apply solely to the elderly; even the young will dehydrate in 10 hours. Yet the city generally ignores these basic elements. For example, in the heart of Milan, an avant-garde city in many respects, the rear of Palazzo Arengario is regularly used as a toilet. Any tourists caught short in the city centre will use a corner to relieve themselves. And this has been going on for decades. There has never been any attempt to prevent this kind of behaviour, let alone find a solution to the problem itself. It is an ancient problem that remains unresolved since the local administration doesn’t take this type of problem into consideration.

In The Reappropriation of the City, produced by the Centre Pompidou in 1977, you claim that it is easier to identify traces of creative behaviour that modify the territory in the city suburbs, where the system is weaker and less efficient. Do you still believe that this is the case?

A little less so and a little more so. In the 1960s, the suburbs were more or less abandoned, in the true sense of the word, but far from marginal in terms of size.

Gordon Matta-Clark, who studied them closely in those years, perceived them differently, seeking small fragments of unused territory – the same fragments that were set upon with a certain capacity for invention and transformation by the locals. There were those who created urban gardens, or other types of temporary and abusive structure. Nobody ever purchased these spaces between the railway and a motorway, it was rather a form of conquest. Consequently, these territories were much more flamboyant then than they are now. They stimulated people who wanted to use manual skills and to create and transform a space.

Today the question of the suburbs is a little different, in the sense that there is indeed the desire and need for transformation, but within a more social dimension – the relationship between the environment and the groups that have formed there. The discussion becomes more complex, almost sociological, and not simply anthropological.

To summarise, in the 1960s, there was this desire to conquer a space and build something, today it is quite different. Today, people wish to make these suburbs into habitable places, that is, suitable for activities, with a purely social design intent.

I would add something banal: a communal garden is the evolution of the private garden, a space that pensioners could conquer and visit in their spare time. It meant there was a transformation taking place, increased awareness, perhaps even a more powerful response from the territory to a common and deeply felt problem. Let me explain better: today the suburbs are not just the scraps of the city but real spaces, with a physical size and vital force that is one hundred times more important than that of the historical centre. They have expanded. They are no longer marginal but a remarkable presence, both physical and social, and therefore also in terms of vitality.

In this regard, there is necessarily a difference between yesterday and today.

Temporary structures have always attracted you. The work you did on the beach in Cagliari comes to mind…

Of course, the Poetto houses.

Why is that?

This is a little too personal, I think.

Well, I have always been fascinated by smaller architectural structures. Poor and modest structures made with very little. This might stem from my formative years, when I lived in my grandfather’s house for a long time – it was a poor dwelling, it didn’t even have running water. We lived on a much smaller scale than we do in our homes today but, for that very reason, what we did have was highly valued.

This has nothing to do with it, but since you asked… When I was 7 years old, I took an old chicken coop and made it into my home: it was small and humble (as I said, it was a chicken coop). In short, this is a personal passion that is closely tied to my childhood and my development.

But spontaneous architecture – and this is the real answer to your question, forget that stuff about my childhood – has always interested me more than so-called cultured architecture. This is because I have always found in spontaneous architecture the values that cultured architecture cannot offer. The same values I find in rural architecture, which was the subject of much of my research in the 1960s. The rural architecture of lower Lombardy, of Salento – stone structures, to be clear – then Poetto, etc. This is where I found the manual component that we radical 1960s architects were looking for: the do-it-yourself approach where the individual builds their own house with their own hands, tools, and structures. This is inevitably the utmost expression of creativity because everyone does it in their own way. This is what I was looking for with my research and am still looking for today. I am still just as attracted to and intrigued by spontaneous architecture as I have always been. At the 1978-79 Venice Biennale, I was able to use all the tools that I had “stolen” from rural environments. I say stolen, I obviously left some money. I went to these houses, these urban gardens, and when the owner wasn’t there (they weren’t always there, they often had other jobs), I left 5,000 – 10,000 lire and took the tools they had made for themselves. They were all tools made with recycled materials; they were incredibly interesting, and I managed to create an exhibition with them.

You have already answered in part what I wanted to talk about next but my point ends with a specific question so I will read it all anyway. In The Reappropriation of the City, you also explore how crucial it is to recover manual and creative activities if we are to awaken the faculties atrophied by the working society. I find this to be a highly contemporary idea, especially since you developed it as part of a process linked to the reuse and recycling of abandoned objects. What is creativity for you?

Well, much was written about creativity in those years. For me, creativity has always been a category to spread as far and wide as possible. My opinion – which remains unchanged today – was that if somebody wants to make music, they don’t necessarily have to do ten years at the conservatory. They can pick up a guitar and play it. And that applies to everything. It means giving society the opportunity to be creative without going through the so-called categories or the various institutions that issue “creative licenses”. Take the architect, the interior designer, the artist, the visual merchandiser… There are so many different categories that define creativity and pigeonhole it into a very precise definition. Society is more and more organised, and it increasingly wants to place you somewhere specific. Creativity, however, disregards these positions, and that is why I also practice this way of life on a personal level. For example, I love music, so I started playing; I have played in an orchestra my entire life without knowing a single note. That is quite unusual. Apart from the fact that I have played alongside some extraordinarily talented people, all I did was rely on an innate characteristic, that of having a good “ear”. The same applies to painting. I have always painted without ever having studied it. I am certainly no Academy of Fine Arts graduate, but I still paint regularly, every day.

Sadly, our society does not share these ideas. Instead, creativity is linked to categories and to models, and therefore to extremely specific constraints.

In both Preferential Itineraries and We are looking for the form born out of our experiences instead of imposed schemes, you place the individual in the centre. Not architecture, not houses but the individual. As though the city were made up of the people who inhabit it and not the streets and buildings that form it. Do you think that this approach is purely mental, or should it be physical? By which I mean, does this attitude also apply to creative discourse? I gave the example of the Preferential Itineraries, but you have tackled it in much of your work.

Yes, it definitely also applies to creative discourse. Precisely because I know architecture so well, both as a student and a scholar (although never having built anything), I have always known that cities are made of individuals. In a country like Italy, where urban centres mainly consist of consolidated architecture that endures and is repeated for centuries, it is easy to reach the conclusion that it is people who make cities, not houses. The houses might be 100, 500, 1,000 or even 2,000 years old… It is therefore obvious that they cannot be truly representative of a place and a society at any given moment.

But what does it mean to place people at the centre today? This is an abstract process within the city. You were saying about creativity…

Placing people at the centre is something that derives from a fairly classic definition for me: a city made of people rather than houses. In this sense, the individual becomes a central element in the recognition of urban movements and the meanings of things; it all passes through people and their behaviour. This is an ancient lesson.

I always think of Munari as an example. He went to Japan (nobody used to go there at the time) and returned with a passion for Japanese culture. He came back and said, “Do you know that half of the world’s population lives without a bed?”. He would say this to designers, to make them understand that design should never start from typology, as they had been taught in universities. “Today we are going to design a chair…”. No, design should always start from the behaviour of the individual. For example: “What can be done to respond to the individual’s need to sleep and rest?”. Well, half the world uses a mat, which they place on the ground and sleep on. Design must always start from the individual, from their behaviour and their rituals, as well as their changing needs. It is from these fundamentals that a creative-design response can be developed.

But this very rarely happens. Instead, design almost always starts from consolidated categories, which might have been outdated for some time without anybody realising. When I did the Telematic House in 1983, I showed how the domestic ritual of sitting around a table for tea was now outdated, interrupted by the presence of the television, which had completely changed the hierarchy of things. But still designers continued to design central tables, with armchairs positioned around them, imitating a ritual that had long been lost. Nobody saw what was really happening inside people’s homes, where they sat in front of the TV as though they were in a small cinema.

This might be why I became quite famous in the world of design. Not so much because I designed something. Nothing I designed has actually ever gone into production. But I always thought it was important to make certain things understood, things that the discipline unfortunately often ignores. Because like all disciplines, it starts from the disciplinary categories, instead of the individual.

The fusion of disciplines, the breaking down of walls, the periphery, public space, private space, the politics of perspective, interactive and relational works… You have pretty much done it all. You are a great designer and you are interested in urban planning, design, and painting… So, who is your inspiration? Who is your role model in the history of art?

I’m going to tell you something that might make you laugh. People see me writing two, three, four books a year and they ask, “Why are you writing all these books?” And I answer, “Leonardo created six or seven works in his life, hardly anything. But he wrote pages and pages describing everything he did, thought and hypothesised…” It’s not that I want to compare myself to Leonardo, but I hope that my identity might be considered similar to his, at least by analogy. Especially since I’ve built practically nothing, as an artist I’ve been asked to do three or four urban projects. When I give lectures, people ask what I would still like to achieve now that I am over 80 and I always reply cheekily that I would like the Municipality of Milan to dedicate a flower bed to me. That hasn’t transpired as yet! But they didn’t even dedicate one to Munari, or Sottsass… These great artists passed through Milan and left not even the slightest trace.

In short, I wouldn’t mind being compared to Leonardo, he only did a few things, but he wrote a lot.

Then at some point in my life I discovered another figure who I won’t say is similar to me but who I feel a certain affinity with, and that is Ponti. He was so at ease in moving from one category to another and overcoming disciplinary models. He did design too but was “sentenced to death” for having created a lot of decorative design with Fornasetti in the 1950s and 1960s, at a time when Italian design was very clean and minimal.

In short, Ponti, who I have studied extensively and also written a book about, is somebody that I have always liked because of the relationship he had with the applied arts, and because of his passion and his desire to be an artist. In reality, he always wanted to be a painter and the fact that he wasn’t caused him great suffering. His most important biographer, Agnoldomenico Pica, wrote that “Ponti always cried because his role model was Campigli; he wanted to be an artist-painter”.

Somebody else that I really like and consider a role model is the architect Vittoriano Viganò. He too had always wanted to be an artist and he only frequented other artists – Milani, Crippa, Dova – during his time in Milan, never architects. Like many others, he was an architect but always felt that he was, above all, an artist. I am also haunted by this. Anyone who lives their life intensely will be faced with obstacles. Take Sottsass, who was banned from building houses. He was a designer, but he wanted to be an architect. It’s not that I suffer from not having built or made anything: my suffering is more related to a certain relationship with the outside world, therefore the city, and the few projects that I have had occasion to work on.

I am currently writing a book and organising an exhibition that will be held soon in Spoleto, where I will bring together the few but significant pieces that I have created for the urban environment during my life.

Don’t worry, this issue is dedicated to the New Renaissance, so…

Yes, I would say it fits.

Something else I wanted to ask is whether you see any relationship between your research into monumentalism and the Star System?

Well, I have always criticised monumental architecture as an undemocratic expression of an intention. But as anybody who is familiar with my work will know, from the early 1960s I designed many architectural structures that I called “urban nodes”. They were almost all bought by the Pompidou. They were quite particular designs, but the point was what they represented: they were meaningful elements inserted into an anonymous and repetitive urban fabric.

Consider, for example, the suburbs of Tokyo: miles and miles of identical, homogenous housing. I thought it was right to create something meaningful within that setting, something that would provide orientation as an “important object”.

Today’s so-called archistars raise a similar discourse yet create “significant objects” in urban contexts that have no need for them, places that do not need an exception to interrupt the anonymity, or repetitiveness. Places such as Bilbao, Turin, Milan… Places with consolidated and historical urban configurations.

Let’s take Milan. Milan is a horizontal city that has no need for vertical interventions. It is akin to dismissing water as a founding element of a city built on water. Whether that is the sea, a river, or a canal. These are cities that already have their own intrinsic meaningful elements, making the introduction of an external “important object” improper. And this is where “monumentality” comes into it, in the sense that the characterising object is inserted into a dimension that doesn’t need it, when these elements could represent a solution or a way to give value/meaning to the homogeneous and anonymous situations found in many other urban spaces – the suburbs, for example.

And so, sometimes, when I look at my drawings from the early 1960s, I realise that I was doing similar things but that they were destined for another dimension on another scale and certainly represented a different choice both in terms of culture and design.

There is no doubt about that.

So, what is the identity of a territory?

The identity of the territory is a concept that will feature in the book I am writing and that I raised several times in the course I taught at the Polytechnic and the Academy. I explain that when you intervene in a space – whether as an artist, architect, or designer – for me, the design must stem from analysis of the territory and its resources.

The territory will always tell you something. Sometimes it is striking: if you go to Ostuni, for example, where all the houses are white; you don’t design a red house. But the resources can often be something much deeper: behaviour, history, stratification. Each territory therefore necessarily has its own identity.

Here in Italy, we have an advantage. Each square centimetre has its own meaning, a stratified value: there is no village that cannot say “this was formerly a Roman settlement, and the Etruscans were here before that…” This is history but also identity.

The project that I asked the students to develop would always be tied to the territory. I often chose particularly challenging realities, perhaps a road with nothing on it. Or perhaps there were three greengrocers there and they were the resource around which to develop the project, because they formed identity of that road. It is easy to go to Salento and notice that Lecce stone is the foundation of the architecture, from the menhir to the Baroque. It is easy to spot physical and material resources, but I like to focus on deeper layers.

Designing for territoriality therefore means engaging with a specific context and being aware of its existing identity, at least in part. In a place like Italy, diversity is excellence: it is the most common expression of the essence of a place. Every village has its own way of making cappelletti (and name for them!), just as people from different areas have their own specific physiognomies. Diversity should therefore be the starting point, especially in a time like this. I was already making this point in the 1970s and 1980s, when globalisation was just taking hold. But what does globalisation mean? It means that either you play the game, but lose who you are, or you celebrate your differences, which is the opposite of globalisation. And that is how certain legends are born, such as the excellence of our wines. Why? Because we succeeded in giving them a strong identity.

You have always worked with local craftsmen, whenever you were invited to work anywhere.

This is precisely the meaning of territoriality and, therefore, design linked to genius loci, the identity of a place. It is something that should be cultivated, especially in Italy, where these values are easily recognisable. This is not the case in France, where you can travel for miles and miles through very homogeneous and repetitive territories and it is much harder to identify certain characteristics.

You will know that collectives have been making a comeback for some years now. And you have plenty of experience with collectives since you have been behind a number of them, starting with Global Tools. I was wondering who you worked best with and what differences you observe between the collectives from those years and those of today, in terms of design. I know you have also collaborated with some young people, so you should have a yardstick…

I am always open to collaborations and working with others. But the collectives that I was a central figure in were always born from particular political and social situations. Because it can be difficult to come together, especially in a city like Milan, which is chaotic and has much to offer. It was only really possible in moments that were historically weak for society – the energy crises of the 1970s, times when there was a lack of work, a lack of opportunity… These were all factors that brought groups of people together. Turin’s poveristi grew out of a city that offered absolutely nothing, just as the radicals of Florence sought a way out of a city that revolved solely around tourism and provided no opportunities. It was the early 1970s when we started Global Tools, the Cooperativa Maroncelli and the Fabbrica di Comunicazione in Milan: a very difficult time, where galleries no longer had a role to play, there was no market, the energy crisis was happening… It was a complex situation. After that, when Milan started functioning again, with the boom of the 1980s and then this third (smaller) boom, this type of collaboration decreased significantly.

Lately collectives have increased again precisely because the crisis has returned. The market has completely excluded architects and designers, who, for example have ventured into self-production… There are no opportunities for them, for sales or commerce or anything. That is why they have started to come together again and to collaborate. As a collective response to a crisis.

That is true but let’s take the magazine “Inpiù” as an example: there was a project, a point of view, and a vision of the city behind it, with a different perspective offered by each collaborator. It was a story that was design-orientated, while today…

Because these magazines were like exhibitions. They would call ten, thirty or fifty people to respond with an ad hoc piece (not their usual work) around a specific theme. There was a particular method behind it, in view of the occasion. It is a bit like the Campo Urbano event in Como, which I always mention. It was the only major interesting exhibition. Not because it was ephemeral (although that did help), not because it was before the great attacks – the Piazza Fontana bombing happened immediately afterwards but until then we were still euphoric and optimistic – but for another reason: the artists that participated did not bring their standard work. When you look at the catalogue, everyone created pieces especially for the occasion, pieces that did not necessarily resemble their usual work. So, it was a highly creative operation based around a theme, which is what I did whenever I organised an exhibition or set up a magazine. There was a theme that the authors had to somehow adhere to and play their part in so that it wasn’t a simple collection, but a set of works put together according to a certain logic. It is not easy to propose this model today, because the Art Director – who is responsible for collecting all the material for an exhibition or publication – is neither an artist nor a creative but usually a curator or historian, no doubt very well informed but lacking direct experience. When I organised exhibitions, I made sure that the exhibition design itself was a work of art. Today, the exhibition designer merely seeks to arrange the artworks so that they are visible, nothing more. When I developed the exhibition design for the Cronografie exhibition at the Venice Biennial, I first imagined a series of structures and boxes that expressed memory so that the setting – before even the work – responded to the theme in question, through an almost physical, certainly figurative factor.

That is what makes the difference. I complain a lot nowadays about not being able to work the way I used to. In the past twenty years, I have only put on my own exhibitions. It is rewarding, of course, but I no longer do things with others or for others. I no longer have that opportunity and I really miss it. I envy people like you who succeed in doing things, bringing people together and building events, which has always been a part of my true nature.

In Spazio Reale Spazio Virtuale, a film made for the XVI Triennial (’79), you tackle the art system: artists, curators, directors… everything that an art event entails. Do you find that the system has changed today or not?

Not at all! This is exactly what I’ve been complaining about of late. The last Triennial was the final coup de grace to what used to be an important and positive tradition, because it used to be similar to what we were discussing before: it had a theme and then, with a coordinator at the reins, it gave a number of creatives the opportunity to create work. To make something ad hoc. As far back as Fontana, everyone knows that the Triennial has always been a place of great experimentation. Where different artists – architects, designers, painters, etc. – were able to create work. Not reproductions of the work in their studios, but elaborations on a theme. It was an opportunity to do something new, whether that was an object, an environment, or a collection.

This has been completely lost. The last Triennial, for example, had an excellent and very current theme but the result was akin to a typical Expo exhibition, where the public is given information about things that might happen, things that will happen, problems, innovation, technology… It was purely didactic, no doubt intelligent and interesting, but not artistic. Society is given an idea, an image of what might be the solution to a theme, in the past, present, and future. Another great thing about the Triennial used to be that all the craftsmen, companies and production facilities competed to finance and implement the different projects, which provided a wide range of opportunities for participants. For example, if you went to a company that produced neons and told them you had to create a piece using neons, they would fund the work. There was a mechanism of complicity and exchange that has been lost over time and certainly no longer exists today.

The Triennial therefore lost that identity as a catalyst for opportunities and Boeri, who is certainly an intelligent, capable, and political person, missed something there. He did not understand that this would result in the Triennial losing the primacy it had always had, as a place of encounters and challenges, as well as a stimulus for the production of beautiful, important, creative, and inventive things. Looking back on the Triennials of the 1950s and 1960s, it is clear that that identity has been lost for some time, but this last intervention has not improved matters. It was an arena of development and now that arena is no more. In that sense, there is no further progress compared to the past. It did attract 8,000 visitors in 10 days though… That is true…

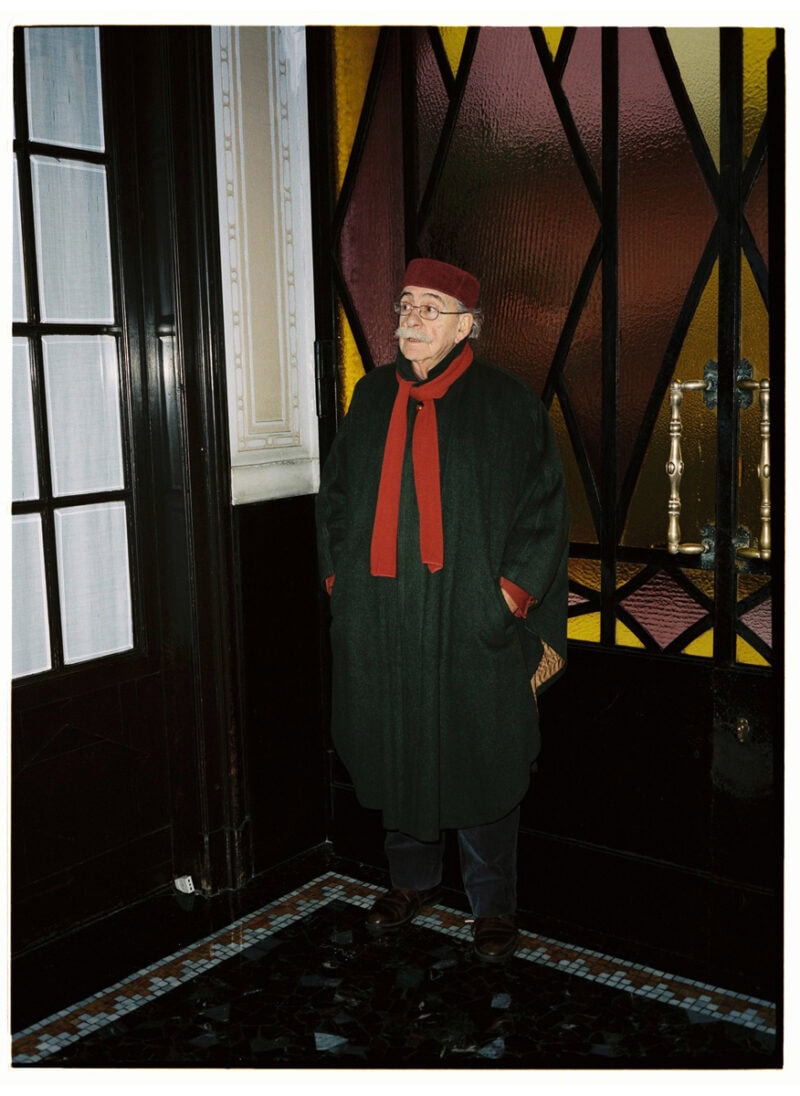

Credits:

Words by Rossana Ciocca

Photography by Leone

Starring Ugo La Pietra