What was the creative spark that inspired this project?

We think that our conversation with Hans Hulrich and curator Rebecca Levine of Serpentine Galleries played a fundamental role. Naturally, we had to work out what was feasible in a gallery that usually only shows art, but which has previously also put on two design exhibitions that were very much in line with our creative journey.

Hans Hulrich asked us to create something for the Serpentine that wasn’t just an exhibition of design products but rather a manifesto of our vision of the design discipline.

This gave us a huge amount of freedom. Often, even in museum contexts which are frequently governed by the museum collections, we are asked to connect back in some way to the product or object which in the collective imagination is linked to the designer, so furniture and so on.

Here, we had the opportunity to take a far more holistic approach to the exhibition content and have greater freedom in the system used to present our ideas. The exhibition has a physical part with different objects and then a part with supporting elements that show the work itself, within which we explored various different media types. The use of video is as important for the exhibition as the physical part.

Wood as a leitmotif is also connected to your long-running creative process. How was it central to the structuring of this exhibition?

Something interesting that we’ve noticed since we started researching the timber industry and working with wood itself, is that it is an animate material, it is alive. It is not like a mineral, which is of course inanimate.

When discussing the timber industry, it is vital to remember that the original source of that timber is a living being. We wanted to focus not solely on the material itself but also on the living being that the material is taken from, which raises various issues, including ethics, that allow us to address more complex aspects of our ideas about ecology.

The exhibition documentation can be divided into various categories and areas: Val di Fiemme, archival research, the museums you collaborated with. How was all this mapped out from a creative perspective?

Research is definitely one of the most important parts of Cambio. There was a very long process of 6-8 months that took place before we even emerged from the studio, during which we read a lot, consulted archives, and scrutinised books on timber and the industry as a whole, as well as a good number on philosophy too.

Once we had fully understood and identified the theme, we then expanded our network, looking for a series of characters and people who would be interesting for our research.

The methodology was quite similar to projects we have developed previously.

There is always the part in which we observe, read and consult existing published materials, and a part where we apply that research, establishing dialogue with specific professionals who have knowledge that you won’t necessarily find in published works.

It is a process that is becoming more and more characteristic of our work and we consider this interdisciplinary aspect to be fundamental. It’s not that we necessarily like collaborating with other designers or architects or creatives, rather it’s about accessing this vast technical knowledge that is rarely implemented in design research. That is what we are particularly interested in.

What role, if any, did Serpentine Galleries have in your research process?

The Serpentine played a supporting role and also connected us with people that we didn’t know personally. Above all, exhibition curator Rebecca Levine really helped us to develop our ideas.

Our research was mostly conducted at our studio, but one institution that supported us extensively was the New Institute of Rotterdam, which put one of their internal researchers at our complete disposal. It was a great help during those months of intense work.

As we have already mentioned, what characterises our work is that we always start from a distance with only a vague idea of where we want to go. Only later, through reading and speaking with various professional figures, does the research area narrow and condense into its final form.

This takes a long time, it took more than a year to get to where we are, which in this case is probably much more similar to the role of a curator than that of a designer.

Val di Fiemme provided much inspiration both in terms of research and documentation. What can you tell us about this experience?

We chose Val di Fiemme for various reasons. Mainly because in 2018 there was a huge thunderstorm that felled over fourteen million trees in a single night. It was an incredibly special and intense event, something that hardly ever happens in Europe. The interesting thing is that, no matter how many people deny it, it was mostly caused by climate change, so we chose Val di Fiemme as a key study to then analyse broader systems.

The thing that probably most interested us about that specific event was the opportunity it offered us: by using the wood from these fallen trees for the exhibition, we were able to demonstrate how designers can make much more contextual and less aesthetic-based decisions when it comes to choosing materials.

We used that wood in the exhibition not because it had any specific technical or aesthetic qualities, but because it was more relevant for us to use that specific material as it allowed us to talk about what happened in the valley. The fallen trees had to be urgently removed from the area before they could decompose and contaminate what remained of the forest.

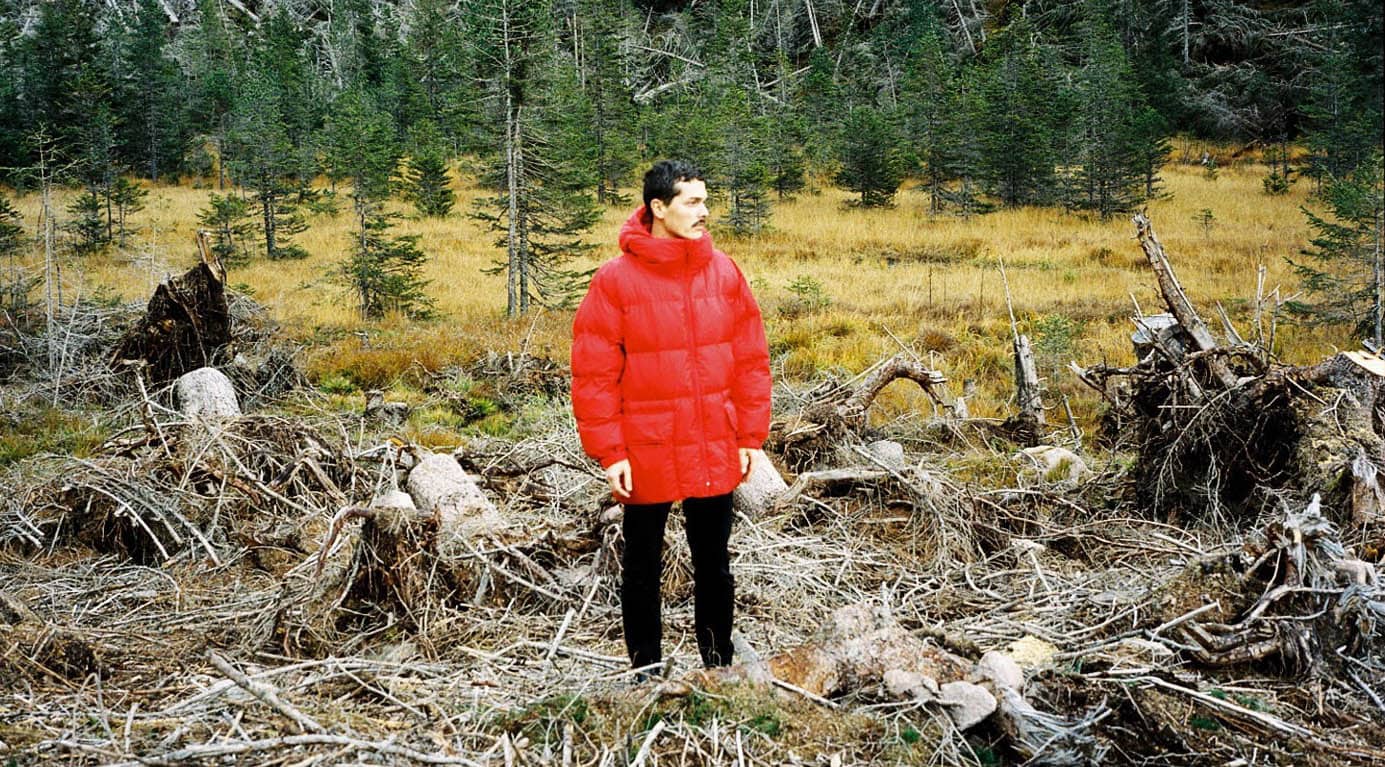

It was a very intense experience. We had seen images of the destruction in the press, but obviously witnessing it yourself and having that powerful awareness that it happened because of the way that human beings treat the planet is shocking because you understand physically, visually, and emotionally just what it means to live on such a fragile planet.

It was literally moving. A mix of deep emotion and disgust. When we got to Val di Fiemme, we began to see the first parts of the mountain where the trees had fallen. That was the most surprising part because there was also a form of beauty in the disaster. The more the days passed, the longer we were there, and the further we went into the valley, the more horrifying it became. I have to say it was one of the most intense experiences I have had since we started working in design.

So there is also a social commentary within the creative process?

Yes, we believe that working in design today has political implications. We don’t mean in terms of Italy’s political strategy but rather that every time we decide to bring an object into this world it has consequences for the workers that produce it and for the environment, and an impact in terms of the way the resources needed for production are extracted, and so on.

In that sense, the work we are doing definitely has a political value. It is an attempt to explore how the consequences of design run much deeper: it can quite simply improve or worsen the life of a user and that has to do with a much wider ecosystem that goes beyond economic development or quality of life, to involve living species and entire ecosystems. That is what we wanted to explore with this exhibition.

Design stands at the crucial intersection between extraction, production, and future recycling, and this central position actually means that we can cause small revolutions if we want to.

Credits:

Words by C41

Photography by Leone

Starring Formafantasma