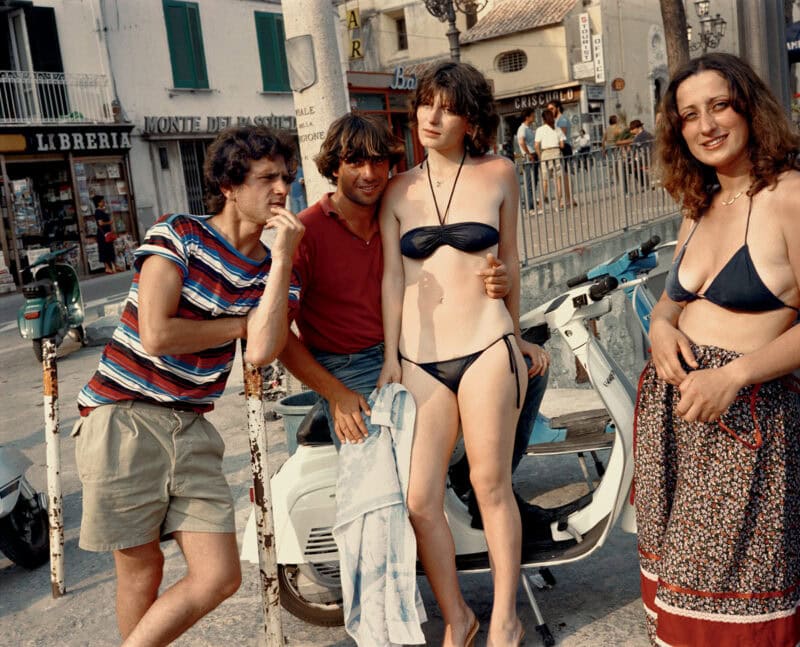

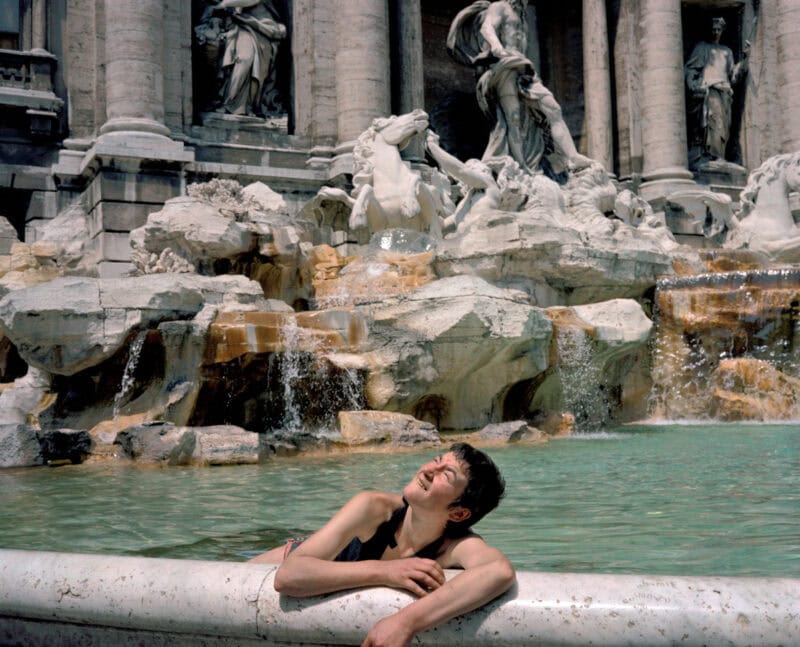

I came across Charles Traub about three years ago during a casual browsing session. I was immediately fascinated by his style and his way of telling stories. It felt as though Traub used his work to preserve the “magic” of what once was. A dive into the past, a close look at traditions, customs, cuisine, architecture, art, etc. I am an Italian born in the 90s and when I look at Charles Traub’s photos for the Dolce Via project, it feels as though I’m looking at a postcard or observing a past that didn’t exist for me, a past that is not part of my history or visual heritage. I have heard stories and anecdotes, of course, but I had never had the opportunity to see what my Italy was like before I was born. It is interesting, almost exciting, to see how little things have really changed. Naturally, the colours were different, the clothes were wider and less revealing, people’s faces had a slightly different physiognomy, not to mention the hairstyles and accessories. But they were still those same Italians who know how to enjoy their free time, dipping their feet into a fountain to cool off on the hottest days, and sinking their fingers into the sand and breathing the seaside air at the first opportunity. We still have the sweet old ladies who tour the markets and crowded pavements in pairs. We are still people who love to be photographed and represented. At first, I found it quite curious that an artist as renowned and important as Charles Traub had decided to focus on Italy but, upon reflection, where else does one find those exaggerated baroque gestures, those colours and an ordinary people who become passionate archetypal caricatures?

As the Lebanese poet Khalil Gibran said: “The art of Italians is in beauty”. Beauty that, in my opinion, can be traced back to its history, landscape, art and food but also to the simple soul of its people. If there is any country outside the United States that often features in your work, it is Italy. What made you decide to do this project? What did you find special or different in the Italian soul?

The Dolce Via photographs were made throughout the early 1980s on numerous trips, some quite short, and others quite intentionally taken to photograph throughout the country. There was no project in mind at the time – but to see, experience, and find out what I could say with my camera. I was using a wonderful one, a Plaubel Makina 67. For that sized camera, it was small and very flexible. My interest, as in my previous beach and city work, was how people displayed themselves – the bella figura.

The project, as you call it, did not really come together until 2012 when I started looking back at my work from the 1980s and realized that there was a wonderful, coherent body of work made in Italy. The idea to do the book was actually prompted by more recent journeys to Rome, Bologna, and other cities where I discovered the Italy of my past was no longer. The expressive Italian gesture, unique dress, and colours were all gone. Travel, globalism, the internet, what have you, have amalgamated everyone into similar modalities. Indeed, a kind of blandness! It is as if what was once a varied salad of colorful plants has been put into a blender and turned into a smoothie. Thus, I thought it worth preserving the “magic” of what once was. As you know the book has been very successful and I think probably because so many people long for the days of the distinctness that was once the dolce vita.

Dolce Via was as well received in the United States as it was in Italy. Obviously, it caught the nostalgia any sophisticated traveler has if they visited Italy during that period.

There is a certain sense of nostalgia in the images from this project. What do you think is the biggest loss suffered due to globalisation and modernisation, and what has improved?

What gets lost in globalization are the idiosyncrasies of individual cultures: folkways, customs, manners, cuisines, architecture, art, etc. On the other hand, you can have a reasonably good Italian meal anywhere in the world and visit the Sistine Chapel and Leonardo’s Last Supper by any means at all. For that matter you can climb Mount Everest and eat sushi in a small town in South Africa, but it ain’t the same and it is not as pure as first experiencing the unique expression of a culture in its original country. Also, it is unlikely you will ever see the Taj Mahal without a crowd or not have to suffer in traffic as you travel through Tuscany.

What inspired an expert photographer such as yourself to carry out this project? What challenges did you face, and, above all, what did you learn from this project – and from these people?

I am a photographer because I want to see, discover, travel, and understand. Being a photographer is an excuse to engage any place, anytime, anywhere.

In addition to the Dolce Via photography project, you mention Italy, and Italians, in some of your writings. You wrote a preface to Luigi Ghirri’s Journey to Italy catalogue where, at a certain point, you say: “For me, Ghirri represents in his persona and his remarkable but short life, all that is wondrous in Italian culture”. How has Ghirri influenced your work and your vision of Italy? What memories do you have of him as a photographer?

Very simply, Luigi Ghirri was postmodern before postmodernism. I was enamored with the wonders of Italy when I met him, its layered history stacked physically and metaphorically one period upon another. Ghirri depicted the irony of one great civilization colliding upon another. With all the foibles, contradictions, and even ridiculousness that paradoxically was Italy. With the exception perhaps of China, Italy is the only country to have produced two great world dominant cultures: the Roman Empire and the Renaissance. Maybe there’s a third legacy: 20th century design and fashion. All of that of course intermingles with its ever-present Catholicism and ancient peasant life. I traveled with Luigi and he showed me those layers. I am forever grateful. By the way, neither of us spoke each other’s language. Lastly, in many ways I believe he is the seminal, unsung colorist of the 1970s.

You produced your second essay with Luigi Ballerini. “Italy Observed” was written after your photography project about Italy, and you define Italy as “the spiritual homeland of all who love art”. What did you see on your journey to make such claims?

If you look at the photographs and read the literary excepts in “Italy Observed”, you understand that from the 19th century and still into the 21st century, travel in Italy was a must for anyone seeking to understand culture and Western civilization. Its art, architecture, and landscape are a foundation of understanding humanism. Every artist has to go back to the Renaissance experience displayed throughout Italy.

If you had shot this project in another part of the world, do you think your personal and professional career would have been different? Do you feel somehow enriched by Dolce Via, not only in professional terms but also in your spirit, as a human being?

I do not think I see any differently in Italy than I do in Kentucky. Like any artist, my photography is an accumulation of experience, practice, and my own criticism of what I do. My spirit is of course formed by what I see. I like people, I like looking at them, I like talking to them. I am curious and a good photographer needs to be so. We understand ourselves thanks to what we take away from others.

Recently we have seen a radical increase in population as well as the huge expansion of cities. How have you seen cities change over the years?

Well, this is a big question. Just like the way we pose and dress, cities all start to look alike too: the same glass building, congestion, and fast food. It is important to note that at least Italy has preserved a good deal of its architectural heritage, but the crowds continue to grow, and the common, artisanal products are pretty much gone everywhere. Lastly, cities are not easy to walk in anymore. They sprawl and at the same time go vertical and you cannot wander aimlessly up and down. However, if you look, you will find that there is visual engagement everywhere. Something serendipitous worth photographing always occurs, which is more fantastic than anything anybody could preconceive.

Have you been back to Italy since the project? How do you think it has changed since the 1980s? What would be different if you had to redo the same project today?

Yes, I go back to Italy practically every year for one reason or another. Of course it’s changed! The major monuments and sites are still there, but they’re overly crowded, particularly in the summer. Rightfully there are tourists everywhere. You have to go deep into things in order to really get the heritage of Italy’s past. It’s not easy to see the Italy in my Dolce Via by just walking the streets. Winter is likely the best time to go, but Italy is always changing, always idiosyncratic, politically unstable, and yet, it still has a vibrazione.

What are your future projects? Are you still focusing on writing and photography or do you have different plans?

I’m still focused on photography, or what I now call the lens and screen arts. Presently, I’m photographing in Kentucky. Wandering its roads and byways, looking again for the irony that such a divided state has today in a politically contentious country.

Credits:

Words by Alice De Santis

Photography by Charles H. Traub