Sofia Elias is a Mexico City–based multidisciplinary artist and designer whose practice drifts fluidly between architecture, sculpture, furniture, jewelry, and public space. Trained as an architect, Elias quickly discovered that what fascinated her was not the faithful execution of systems, but the playful act of bending, misusing, and reimagining them. Her work resists rigid categorization: chairs wobble, playgrounds become sculptural landscapes, and jewelry behaves like intimate architecture for the body.

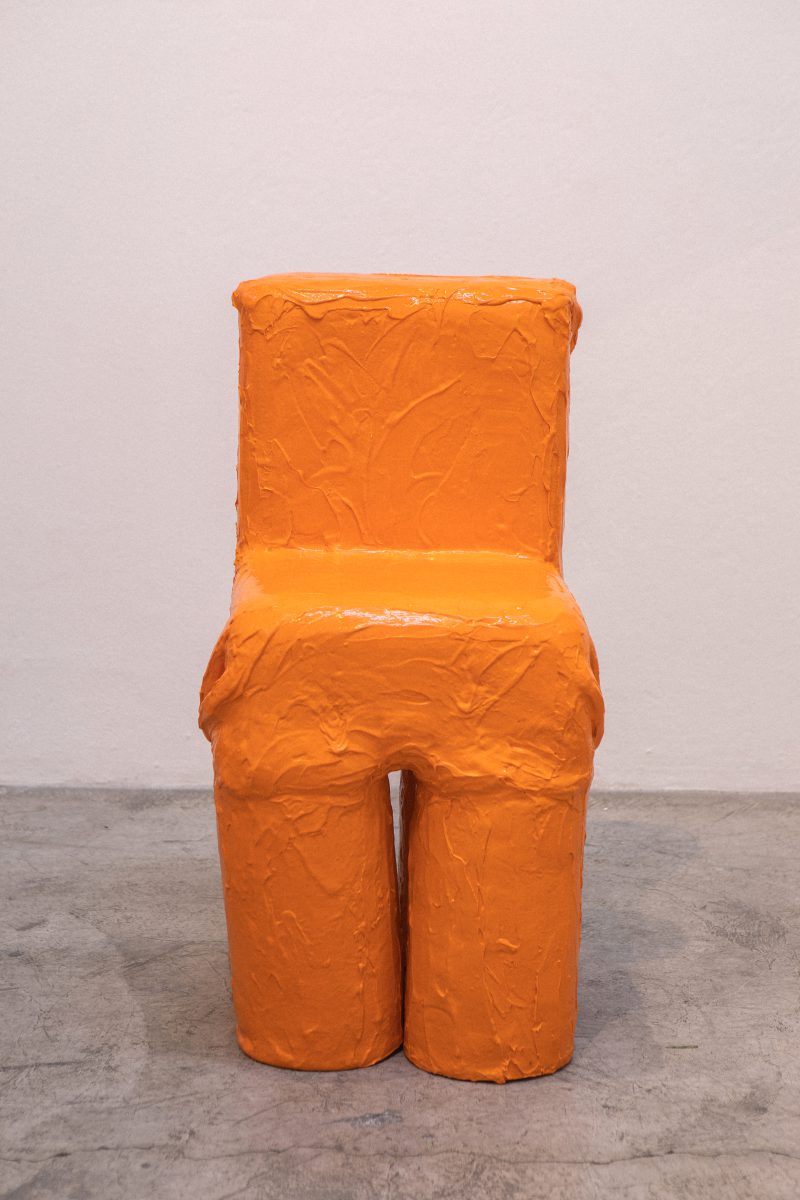

Through projects such as the tactile and unstable Pofi Chairs and her ongoing exploration of play as a spatial language, Elias challenges conventional ideas of function and comfort. Instead of designing objects to be passively consumed, she creates forms that demand physical negotiation and emotional presence. At the heart of her practice lies a simple but radical proposition: that play is not leisure, but intelligence — a way of thinking through the body, and of re-learning how to inhabit space with curiosity and vulnerability.

Athena Kuang: You trained as an architect, but your practice seems to live outside of typical constraints. At what point did you realize you were more interested in playing with systems than following them?

Sofia Elias: I love your question and the way you word it. Thank you. For me, architecture is really the most beautiful, complete career. Sadly, in my university, after the first year, I was feeling more like an engineer than an architect. My school was very technical, so I made sure to constantly be looking for a way to grow the creative side on my own.

Architecture trained me to understand systems deeply: order, structure, logic, rules. But pretty early on, I realized that what excited me wasn’t solving the system “correctly,” but testing how far it could bend before it failed or transformed.

During my studies, especially while working on my thesis, which was a playground, I found myself less interested in delivering a resolved, functional proposal and more interested in what happened when I misused materials, scaled things incorrectly, or followed intuition instead of protocol. That was the moment I understood that my relationship to systems was playful, almost mischievous. But for sure, to enter, disrupt, and see what new behaviors could emerge from those “systems,” I first had to study, understand, and learn them.

AK: Many of your pieces, such as the Pofi Chairs, invite touch, movement, even imbalance. What does the body understand that the mind doesn’t?

SE: The body acts, the mind controls.

The mind understands risk, weight, hesitation, even curiosity — things the body instinctively tries to neutralize or control. When you sit on a Pofi Chair and feel slightly off-balance, your body immediately responds before your mind can label it as “wrong.” I’m very interested in that split second, where instinct takes over and you become present. The body is honest. It doesn’t pretend comfort if it’s not there. It teaches us through sensation rather than explanation.

In this split second, what I’m looking for and always love to observe is the reaction of adults sitting on these chairs. Adults seem to always have “everything put together,” and the minute they sit and fall, the body lets go, and there is an uncontrollable giggle that comes out of almost everyone. And this simple smile is our true self.

AK: Playing to Play proposes play not as leisure, but as a language. When did play become a serious tool in your practice?

SE: Play became serious in my practice when I realized it wasn’t about fun — it was about how form speaks to the body. Play allows you to enter states of curiosity, vulnerability, and experimentation, and many other emotions. Once I understood that play could generate knowledge, form, and meaning, and not just fun, I began to treat it as a methodology.

Through reading many architects and thinkers, I began to understand play as a kind of language. Not something decorative or secondary, but a way space gives signals: where to climb, where to pause, where to gather, where to hide. The body understands these invitations immediately, without needing explanation.

That’s when play shifted for me from being a theme to being a tool. I stopped focusing on objects with fixed meanings and started creating forms that people complete through movement, imagination, and physical engagement. Play became a way to build relationships between space, object, and body. Something instinctive, social, and open-ended. A way of forming community.

It became serious the moment I understood that play is another form of intelligence.

AK: You move between jewelry, furniture, and public space with ease. Do these shifts feel natural to you, or do they come with moments of doubt?

SE: They feel natural because I don’t really see them as different categories. For me, it’s all sculpture, just at different scales and levels of intimacy. A ring is a sculpture for the body; a chair is a sculpture you negotiate with; a playground is a sculpture you enter.

Of course, there are moments of doubt, especially when the outside world expects you to specialize. But whenever I listen to that doubt, the work becomes less honest. So I return to scale as a tool, not a boundary.

AK: You never use molds, allowing each piece to exist as a singular body. Is this a resistance to replication, or a way of staying present in the process?

SE: It’s both, but more than anything, it’s about presence.

In reality, the reason why I don’t use molds now is because at the beginning I didn’t know how to. I was playing with different materials and seeing the outcome of each, looking at all the different results.

Working without molds forces me to stay attentive to the material, to my hands, to my time. Replication creates distance; it allows you to disengage. I want each object to hold the moment of its making, including its perfect imperfections. Those irregularities are not flaws; they’re evidence of a relationship between me and the material.

AK: Themes of childhood resonate throughout your work. What do children understand about space that adults forget?

SE: Children move through space before they judge it. That’s the first thing we forget.

A child doesn’t see a staircase as “circulation” or a plaza as “public realm.” They experience echo, shadow, warmth, distance from the ground. Space, for them, is not abstract — it’s physical, emotional, and immediate. They understand scale through their bodies. A ceiling isn’t “three meters high,” it’s huge or cozy. A corridor isn’t efficient or inefficient, it’s a tunnel, a runway, a secret passage.

I like to say that when we are kids, we are the most pure version of ourselves.

We, as adults, tend to accept space as something given, something already defined — no more curiosity, no more wondering. Children negotiate space through their bodies, through imagination. They don’t ask permission from function. I think my work is about remembering that freedom, cultivating curiosity, and I hope it makes people wonder.

AK: You’ve spoken about wanting to work at full sculptural scale. What kind of space are you dreaming of occupying next, and how would you like to fill it?

SE: I’m dreaming of spaces you don’t just look at, but move through slowly; spaces that feel almost bodily themselves. I want to work with scale that allows for hesitation, rest, play, even confusion. Not monumental in a traditional sense, but immersive and soft, slightly unstable, maybe even awkward.

I want to fill space with objects that don’t dictate behavior, but invite it — to create environments where people can relearn how to listen to their bodies and to each other.