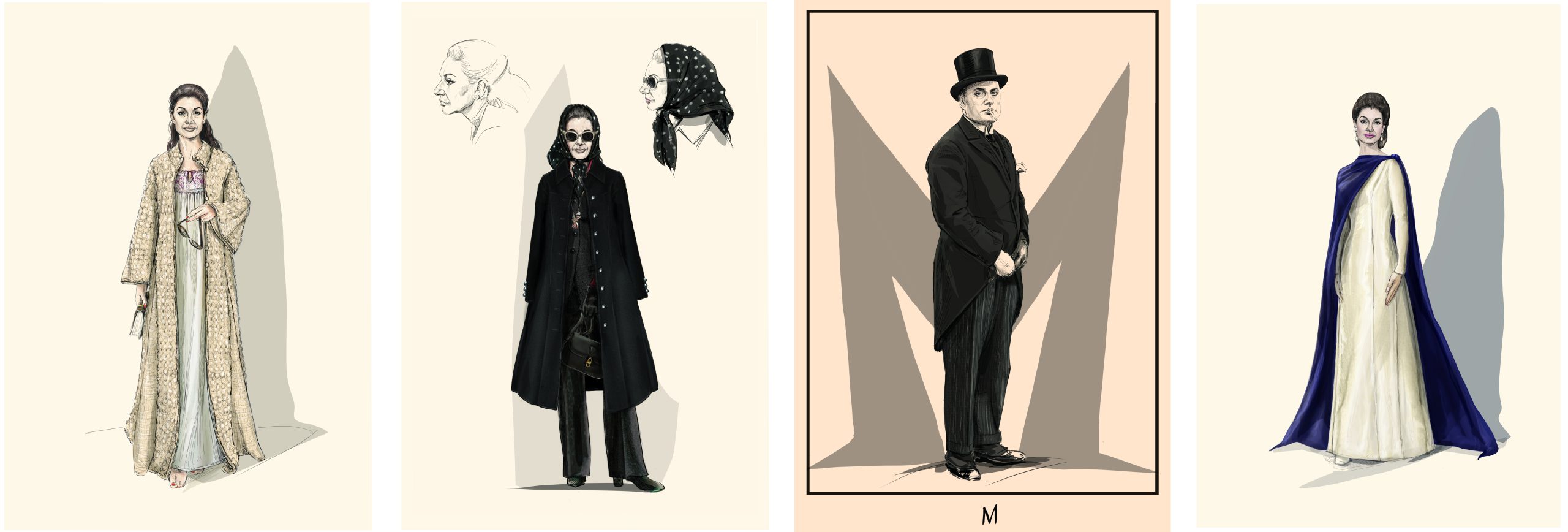

Massimo Cantini Parrini is one of the most acclaimed costume designers in contemporary cinema. His career is a testament to both mastery and vision.

Renowned for his meticulous research and emotional sensitivity, Cantini Parrini blends historical accuracy with a deeply personal, poetic approach to costume design, where every fabric, cut, and stitch becomes part of the storytelling. Now a mentor for the Master in Costume Design at Polimoda, he shares his knowledge and artistic legacy with the next generation of creatives. In this interview, he opens up about his beginnings, the evolution of his work, and the hidden layers of meaning woven into each costume.

Giorgia Pedini: Your grandmother, a seamstress, deeply marked your childhood in Florence. What is your earliest memory of her work and of a garment that struck or fascinated you?

Massimo Cantini Parrini: My earliest memory (as a child) of my maternal grandmother, a seamstress, is tied to two sensations: the unmistakable smell of fabrics and the light streaming through the windows of her atelier. I was struck by the perfection she put into details, and even then, I understood that costume, seen as fashion, was not just about aesthetics, but a true narrative linked to the human being.

GP: You began collecting historical garments at a young age. How did this passion turn into an archive of over 4,000 pieces? What is the most precious item you own—not in economic terms, but emotional ones?

MCP: My passion for historical garments started as a kind of personal journey through time. I began with antique clothes kept in my family, and each piece I acquired since has become a small piece of a mosaic that continues to fascinate me. The piece I value most emotionally is a wedding dress with no real monetary worth, but it was the first I ever bought, at the first vintage shop in Florence when I was 13. Its story and still-intact fabric connect me directly to a past that lives on through me. As they say, first love is never forgotten. Over time, the collection grew and now includes garments and accessories from the 17th century to the 1990s. It’s a constant source of inspiration for every film I work on.

GP: The world of fashion and film costume follows different dynamics. In your opinion, where do these two worlds intersect and influence each other?

MCP: Fashion and costume may seem like separate worlds, but they are deeply connected. Fashion reflects the present and its trends, while costume, at least in my work, serves narrative and character development. What unites them is the design’s ability to evoke emotion. Fashion often anticipates what we later see in cinema, while cinema can immortalize certain aesthetics, bringing them into an imaginary, timeless space. Ultimately, the costume was once fashion, and fashion will one day become costume; that’s the point where they meet.

GP: Costume is often described as a visual language. Is there a film in which you used color or materials in a particularly symbolic way?

MCP: In all my films. Each project gives me the chance to explore the visual language through costume. But if I had to choose one, it would be Cyrano by Joe Wright. In that film, colors and materials became tools for expressing the characters’ contradictions and emotional nuances. The costumes weren’t just aesthetic; they reflected the balance between elegance and simplicity, amplifying inner emotions that words couldn’t always capture.

GP: What has been the most emotional or surreal moment in your film career? A memory you hold particularly dear?

MCP: There have been many emotional moments, but one of the most surreal was the first take on my first film as a costume designer. Seeing those characters brought to life through the creations I had imagined and designed was unforgettable. One dear memory is from a set in Prague. We had crafted what I thought was a perfect costume, but one detail didn’t sit right with me. I discussed it with the director, and our conversation led to a small change that made the costume even more fitting for the character. That’s when the magic of collaboration truly happens.

GP: Your costumes are known for their obsessive attention to detail. Have you ever included hidden elements, personal secrets, or references in your work?

MCP: Every costume I design is like a small puzzle, and I often include details that only those familiar with the history of the costume or the character might notice. Sometimes they’re historical references, other times I include personal touches. I believe a costume should always be more than what it appears to be. If it manages to suggest something deeper to the viewer or the actor wearing it, then it has fulfilled its purpose. I always strive to reach the true essence of the era I’m recreating.

GP: What has been the most complex scene for designing costumes in your career?

MCP: One of the most complex scenes I remember was from a historical film where we had to show a radical transformation of the main character. The protagonist transitioned from a regal and formal look to a simpler, humbler one. Every detail had to reflect that emotional shift without being too obvious. The challenge was to convey that evolution through subtle changes in fabrics, colors, and shapes. That said, the most demanding scenes are always those involving large extras, where everyone still needs to be individually characterized.

GP: Have you ever had creative differences with a director over a costume? How do you find the right compromise between your vision and theirs?

MCP: Differences are part of the creative process and, in the end, they’re essential. Every director has a clear vision, and my role is to interpret that vision. If differences arise, I always look for a compromise that respects the director’s vision while staying true to the costume’s purpose. Confrontation is key: finding solutions that satisfy both sides without losing the character’s essence. But ultimately, I’m never fully happy or convinced by what I do, it’s the eternal dilemma of every artist.

GP: Is there a film you’ve worked on where, looking back, you’d change something about the costumes? Or a detail that now makes you think, “I could’ve gone further here”?

MCP: As I mentioned before, I’m never fully satisfied. There’s always something I would change. Every creative work leaves room for improvement and, sometimes, for reconsideration. Looking back at some films, I notice small details I would now approach differently, thanks to the experience I’ve gained. Maybe I would’ve dared more with color combinations or fabric choices. But that’s the beauty of creative work: you never stop learning and evolving.

GP: You chose to return to teaching with the Master at Polimoda. What is the most important lesson you hope to pass on to your students?

MCP: The most important lesson I want to pass on to my students is that costume is never just clothing, it’s a language. Every choice should have a reason, every detail an intention. The costume serves the character and their evolution, not just aesthetics.

GP: What is the greatest lesson you learned from your own mentors?

MCP: The greatest lesson my mentors taught me was not to be afraid to take risks. Creativity is an act of courage; you always have to push beyond boundaries and never settle for the easiest solution. My mentors are three: Cristina Giorgetti, Piero Tosi, and Gabriella Pescucci.

12. What made you return to teaching after such an extraordinary career in cinema?

After so many years spent on film sets, I felt the need to share my experience and knowledge with new generations. Teaching is a way to give back to the world that gave me so much, and to pass on a part of myself.

GP: Cinema is changing, with new technologies, CGI, and artificial intelligence. Do you think the role of the costume designer is under threat, or will it evolve?

MCP: New technologies inevitably change cinema, but the role of the costume designer isn’t threatened. It will evolve. Technology can be a useful tool, but the essence of costume remains a human act, made of emotions, instincts, and sensations that no machine, no matter how advanced, can fully replicate. Our work is still handmade.

GP: If you imagine the future of costume design in ten years, what do you see? Is there something you hope will radically change?

MCP: In ten years, I see costume design becoming even more integrated with a film’s visual storytelling, where the lines between digital and physical become increasingly blurred. I hope that despite the rise of technology, the value of “handmade” craftsmanship and the artisan skills that make each costume unique will continue to be cherished.

GP: A costume can tell a story just like a screenplay. If you had to choose a single costume to represent yourself, what would it be and why?

MCP: If I had to choose a costume that represents me, I think it would be a classic garment with unexpected details. A piece that looks traditional at first glance, but reveals something personal upon closer inspection, like a hidden embroidery or a unique color choice. A bit like my vision of costume design: classical in structure, but always ready to tell something unique.