Maria Maaneskiold is a Norwegian artist based in Oslo. She holds a BA in Art Direction from Westerdals Oslo ACT, and has five years of experience as an art director – along side of freelancing as an award winning illustrator and artist. Her mediums are mainly illustration and painting, though in the recent years she has also experimented with sculpture and performative work. Her perspective often merges personal life experiences with a more «magical», imagined reality, and alludes to escapism and fever dreams. It connects to the recurring topics of the psychological relationship between adulthood and childhood, when the lines are blurred. Social boundaries, and is also influenced by her conceptual background.

Ilaria Sponda: You’ve spoken about considering yourself in between the artistic and commercial fields of illustration, being an art director and artist. How do you define yourself as an artist?

Maria Maaneskiold: My family consists of generations of art directors and graphic designers. I was always surrounded by ideas, and dragging invisible strings between things to connect them was a game for us. My grandmother would say for example «Maria, look at this rock, it sparkles like a treasure». And then the connection would be made. The rock, which was just a rock before, was transformed mentally into a real treasure. This way of thinking for me and this was initially why I pursued advertising, like my relatives before me. But it has also largely shaped my artistic practice. Because of this, I would define myself as a conceptual artist working visually.

IS: And in your personal life, where do you sketch your drawings most? What’s your relationship to it?

MM: I sketch everywhere. I feel like I leave a trace of sketches everywhere I go, but usually I do it because I’m restless or bored. I was never one of those artists who could complete a sketchbook full of beautiful drawings. Though I have tried countless times. The sketches that become finished work is often done through a different process with more concentration and focus. I do it when I need to put into form an idea of a feeling or a shape. I’m usually not able to visualise something completely in my head, so I always have to sketch to figure out exactly what it is I’m thinking about. I often sketch the same thing over and over again to change things and have it feel just right. I rely pretty heavily on my sketches when completing a painting, and the finished piece will usually be very close to the sketch.

IS: How did you start getting into illustrations? And where do you think the thin line between commercial work and artistic work lies?

MM: I don’t really remember a time where I wasn’t drawing, and I’ve never thought about it as something I choose to do. To be honest, I think I’ve continued doing it for so long because I have always been told I’m good at it, and eventually it’s become a big part of how I communicate. I guess that’s where the connection between the commercial and artistic sides of illustration lies for me. Both are tools we use in an attempt to communicate something. And when it intrigues me the most it often has an idea at its core. Something that puts two or more things we are already familiar with together in a new way. That said, I’ve been very lucky with my commercial commissions in regard to artistic freedom. People usually want me to create in my style – which again gives me the space to think more abstractly and philosophically than what classical advertising does.

IS: You’ve recently been spending some months in Milan as an artist in residence at Viafarini-In-Residence. How did your work develop?

MM: Milan became my home away from home so fast, and I started missing it immediately the second I left. What made it most special was the people I met there, and also the time to focus on a project for a longer and more continuous amount of time. Time is so valuable. I know, super cliché, but it’s a bit underrated at the moment in my opinion. We expect everything to go super fast and are super restless. We don’t really prioritise or appreciate that really good things take time to become good. I wouldn’t know, but I guess it’s not so different from raising a baby. You’d kind of want them to end up well-rounded and interesting, so you need to give them time to experience something. Throw some shit at them so they become strong and hardcore. I felt like I really could raise my paintings well in Milano. It has also been such a luxury to have time to experiment with new techniques. For example, in regards to making my work easier to preserve I found a way to start working on canvas rather than paper, which is what I usually work on. I’ve preferred paper in the past for the smooth texture that gives me a lot of precision and option for small details, but it’s very fragile. To get the canvas as close to paper as possible, I’ve been coating it with many thin layers of gesso that I sand in between each layer, and It gets so smooth. I really like it. Another big one was, I started playing with natural pigments. It’s been super fascinating and inspiring to work with because it’s kind of alive. It’s sort of like being a chemist. And the only way to figure out exactly how to make it work for you is by experimenting with it. It’s something I’m going to continue working with for sure.

IS: What are you generally exploring through your art practice?

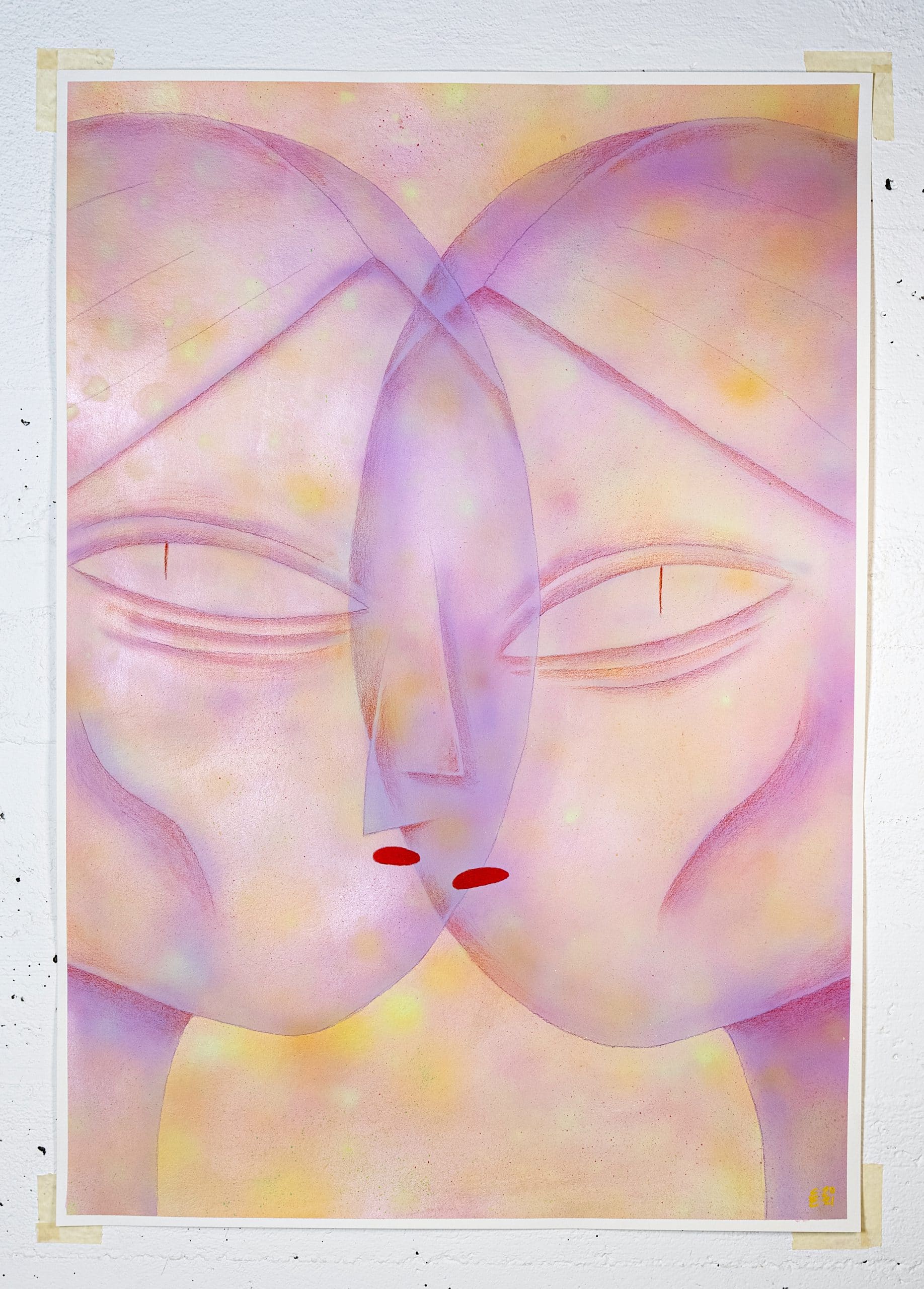

MM: The core of my work is generally focused on how women experience and cope with life. As I grow older the experience of womanhood changes – and so my work also changes. How it is to deal with aging. Questions about fertility. Career. You know, the whole thing. But maybe also in particular, since women often are placed, or end up in submissive positions, naturally I also focus a bit on the topic of unbalanced power dynamics, in interpersonal relationships. However, that might manifest itself. I think it fuels me to kind of poke at the wounds that so many of us have regarding this. Super cliche, but it’s very therapeutic. It’s like when you get a splinter in your foot. You can walk fine, but it hurts until you get it out. And it’s nice to discover that your feelings are normal. I know it’s not rare to me in any way, and that’s why I always come back to it. Because I’ve been told that I’m opening up the conversation around a touchy subject, that’s relatable to a lot of people. In my experience, we women are often subject to sexual attention from a really early age. My point is – a lot of girls can relate to the feeling of being groomed to please. It can be so ingrained that we don’t even recognise it.

IS: I love those pieces where natural pigments taken from orchids almost disappear. It’s a very subtle or romantic way to honour plants and put into practice in your own life the topic you research about.

MM: Yeah, in the end, there was only a shadow left of the flower. Which is beautiful to look at, but also kind of sad. To me, plants hold a lot of mystery and I’m very drawn to things we don’t know a lot about. It means anything can be true. I think that’s where my plant obsession comes from too. For example, I’ve heard that plants are releasing a sort of collectively silent scream, in a frequency inaudible to human ears, when they need water. I have no idea if it’s true, and it freaks me out to think about it. But I love that they might have this secret life that we know very little about. When we don’t know something, there’s a chance for anything – and I sort of use that liminal space as a place to explore my own emotions.

IS: How do natural pigments shape the narrative and the visuals themselves?

MM: I used the orchid as my muse to mimic a relationship with an unbalanced power dynamic – as it is a lot smaller than me. Very fragile, and very beautiful. It also never asked me to be there and serve as my muse. A lot of my previous work has been from a submissive perspective, so the point of this particular project was to turn that dynamic on its head and put myself in a position of power. Kind of to try and sympathise and understand why people take advantage of others. It didn’t need to be an orchid in particular though, but when I came to Milan and started searching for a flower, I found this one that looked like it sort of had a face. I felt immediately drawn to it. I also didn’t want to only use it symbolically but use it physically as well. Something that for me took it one step further, and made the relationship more serious – because I actually had to destroy something beautiful to get what I wanted. Shit kind of got more real. The paintings depict the story of our relationship from my point of view, and the orchid pigment around the border connects the paintings together as one continuous story about the flower. I think it also gives viewers an awareness of the real presence it had before it was destroyed.

IS: What are your most relevant visual references?

MM: I grew up obsessively watching, and escaping into cartoons and playing games. I did it so much that I think it changed something visceral in me. It felt like a place of peace where I didn’t really have to think or be present in the real world. As an adult I’m still drawn to that. My favourites were Samurai Jack, Courage the Cowardly Dog, Dexter Lab, Cow and Chicken, Power Puff Girls, The Jetsons–basically anything Cartoon Network. And studio Ghibli’s ouvre like Nausicaä and The Cat Prince. The game Myst was also a huge early influence. Nowadays I take a lot of photos and use them as a reference. Usually of plants, textures or anything really that feels inspiring and relevant. Sometimes also certain graphics of street signs. I also use self-portraits quite a bit.

IS: What is your ideal creative process and where does it take place?

MM: The ideal creative process should contain, time, money, space, cigarettes, and love. And maybe a dog. But It can literally take place anywhere, as long as I have my noise cancelling headset. I love just getting lost in my head, and when flow happens. I still watch a lot of animated stuff, but I also find the same escape in other places now. Like books, movies, music, or just stuff that I see from day to day. It doesn’t really feel like escaping anymore I suppose. It’s kind of become more a world of my own that I go to. So the reference photos I take, the music I listen to – everything is kind of curated to fit into «my world». I know how it sounds, looks, and feels. So I just listen to music and go. A lot of the time I have little seeds of inspiration that I sketch or write down. And sometimes I find use for it. I love the feeling when I’ve been thinking about something for a while – can be a technique, a subject, or whatever. And then everything suddenly clicks, and I know exactly how to use it.

IS: You’re moving more towards sci-fi, more towards solarpunk narratives in a way. What’s your take on this movement?

MM: I’m super into it. I’ve always had a dream of living in a greenhouse. During my time in Milan, I would fantasize daily about an apartment in Bosco Verticale. There’s really something about trying to understand and empathize with nature that is super intriguing to me, as you know. Maybe because, in my opinion, humans by nature are kind of destructive, and have a need to dominate. Through the work at Via Farini, I was experiencing such a feeling of cognitive dissonance, as I was in this dominant relationship with the flower – while all the time I wanted to take care of it and love it.

IS: How do you see botany and art interacting?

MM: I don’t really know, but Mother Earth’s Plantasia by Mort Garson is literally the best, so I’d love to see an exhibition made for an audience of plants.