Incipit

Via Stradella 7–1–4

opening 25 Settembre 2025

25 Settembre – 23 Dicembre 2025

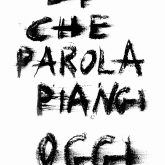

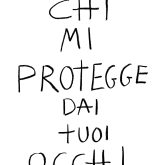

There are words that do not simply ask to be read, but strike instead like blows—sudden fissures tearing through the fabric of reality. Marcello Maloberti’s Martellate do not belong to the realm of measured writing: they are frontal apparitions, visionary slogans, flashes oscillating between poetry and vandalism. Each phrase is both an archaeological fragment and a performative gesture, an act that shouts and resists, that confesses and sabotages. In this encounter, Maloberti offers us an instinctive, plural self-portrait, where language becomes body, gaze, breath.

It is no coincidence that the Martellate stand at the center of his new solo exhibition INCIPIT, opening on September 25, 2025, at Raffaella Cortese in Milan, marking the gallery’s thirtieth anniversary and following his retrospective at PAC. Conceived as a non-progressive, unresolving Via Crucis, three brass plaques engraved with an unpublished phrase recur across the gallery’s three spaces, turning language into threshold, insistence, and echo. In parallel, at Albisola, La conversione di San Paolo evokes Caravaggio’s drama of fall and revelation as a structural trauma, opening onto a void that is both absence and intensification.

Thus Maloberti’s writing expands beyond the page, becoming a space and a condition to inhabit: an exhausted oracle, a mantra that seeks to inscribe itself onto the very surface of the city through those who traverse it. An invitation to live language as a radical, unstable, and inevitably collective experience.

RITAMORENA ZOTTI: The words you choose seem to emerge from a short circuit between poetry, pop culture, and a vandalistic gesture. What makes a phrase, for you, “worthy” of being hammered?

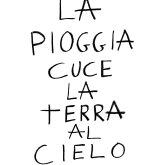

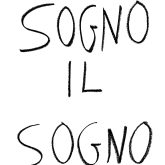

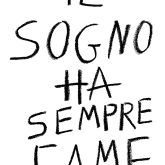

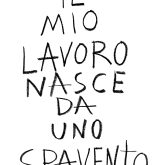

MARCELLO MALOBERTI: The Martellate are absent words/images. Blunt, brazen, like something you would rather not hear, they linger in your head and hammer away. Each one is a curtain opening. They are phrases thought, felt, or even stolen—almost WRITTEN-ALOUD phrases.

RZ: You have built an ephemeral monument to instinctive language: quick phrases, sharp thoughts like cuts. Have you ever wondered if Martellate is more an exercise in resistance or liberation?

MM: They are a collection of impulsive fragments: each phrase presents itself as a world of its own. I love the concept of the fragment, understood as a kind of archaeology of the word. My phrases range from poetry to irony. Sometimes they are characterized by a sense of liberation, other times of resistance—it is an incessant succession of moods and different formal registers.

RZ: Your phrases seem made to be seen before they are read, as if their meaning arrived all at once, like a flash. What is your relationship with the time of reading? Are you more interested in the glance or the rereading?

MM: The Martellate are like instants, they create an immediate encounter with the reader. Reading my Martellate is like continuously zapping on your phone. They are direct, like images. I think the word has the function of “calling,” as if it were an oracle.

RZ: Martellate collects an archive of obsessions and intuitions. Have you ever found yourself rewriting, censoring, or reconsidering one of your phrases?

MM: My phrases are often uncomfortable; I believe in the instinctiveness of thought. It’s as if I were eavesdropping on the world, gathering reflections, idiosyncrasies, ideas, paradoxes, emotions, and then returning them as concise slogans that make you smile and at the same time sadden you, that irritate and comfort, that clarify and confuse.

RZ: There is something physical, almost muscular, in the way you display words: suspended, shouted, engraved. Do you think writing can have a body, or even a gesture?

MM: I also feel words physically, I perceive them almost as if they were shouted. I think the act of writing is very performative. I believe in the strength of the sign becoming meaning. My phrases are black on white—simple yet eternal. The Martellate stand out sharply and monumentally against the white space of a page.

RZ: Some phrases resemble slogans, others intimate confessions, others still small acts of sabotage against common sense. Have you ever thought of the Martellate as a form of discontinuous self-narration, a fragmented diary?

MM: The Martellate are like ruins, fragments, ideas. I believe that taken all together they constitute my most authentic self-portrait. After all, the very name Marcello comes from the Latin Marcellus, meaning “little hammer.” THE SELF-PORTRAIT IS EVERYTHING I DON’T DECIDE.

RZ: In your work, beauty often coexists with disorientation, excess with precision. To what extent do the Martellate convey, in your opinion, an affective and unstable portrait of contemporary reality?

MM: When I write, I also use the gaze of others—THE ARTIST USES EYES AS HANDS. I try to give breath to the word, and I like it to get dirty with the city, with the landscape, and certainly with the reality that surrounds me.

RZ: Is “writing” still a radical act today? Or is it its context—a wall, a sheet of paper, a record—that makes it a political or poetic gesture?

MM: WRITING IS A VOICE BENT BY HAND. I believe that right now there is more need to say than to show. It’s as if I no longer feel the need to create forms or images, but to create messages, to use language that, from private and intimate, often offers itself to a public, collective dimension.