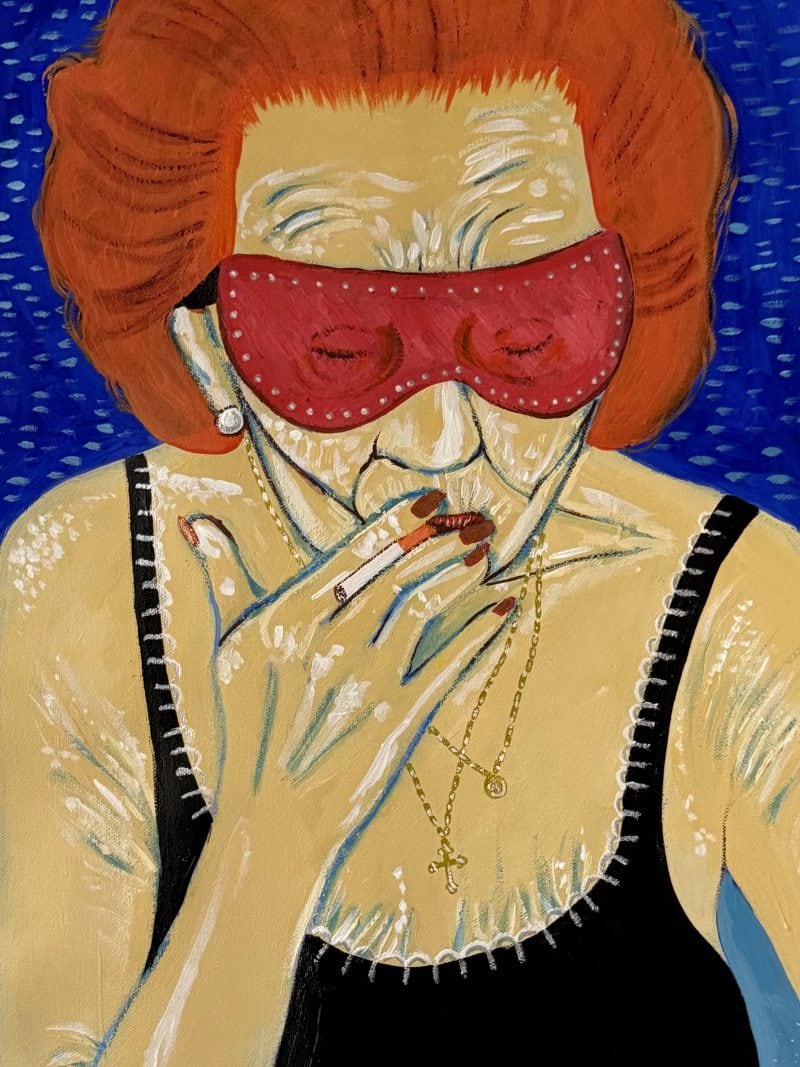

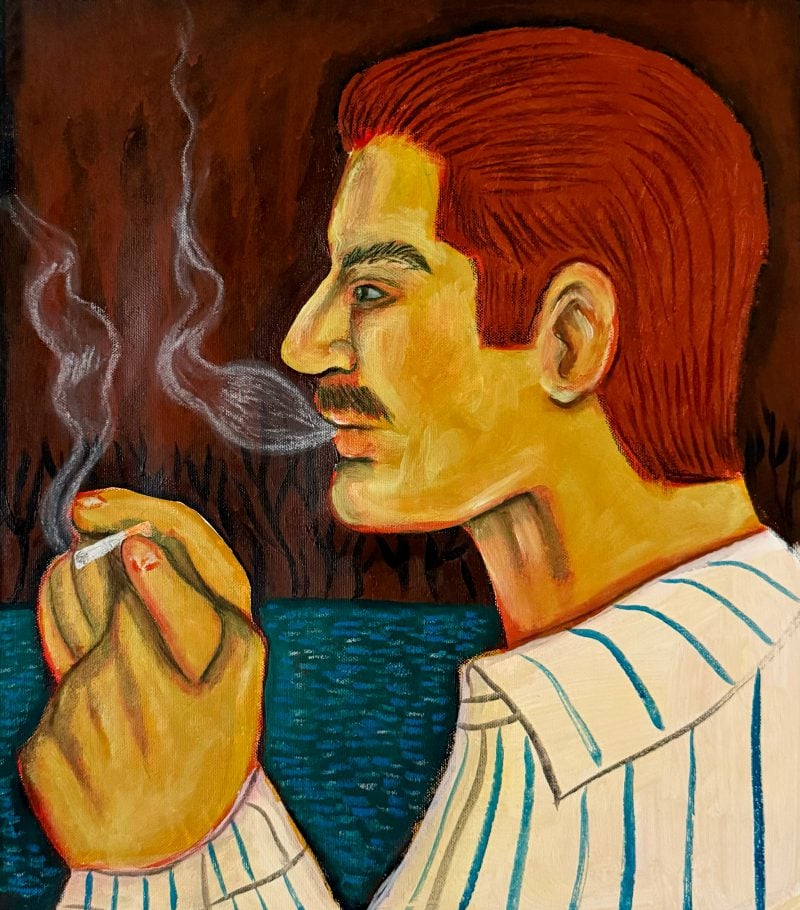

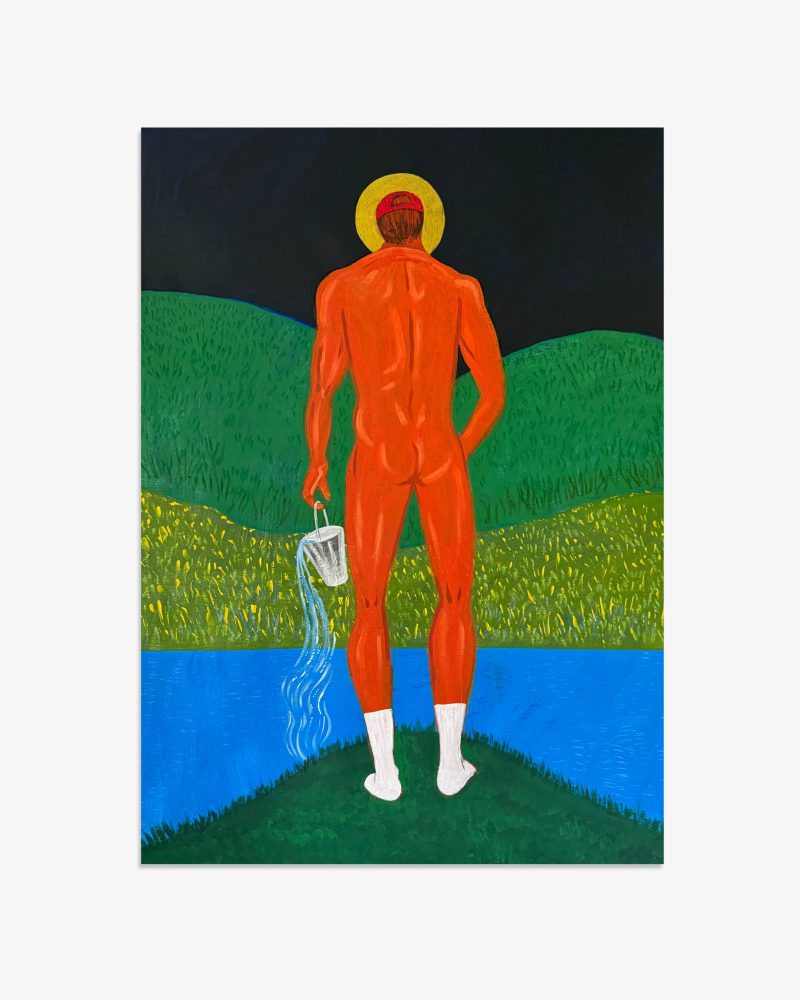

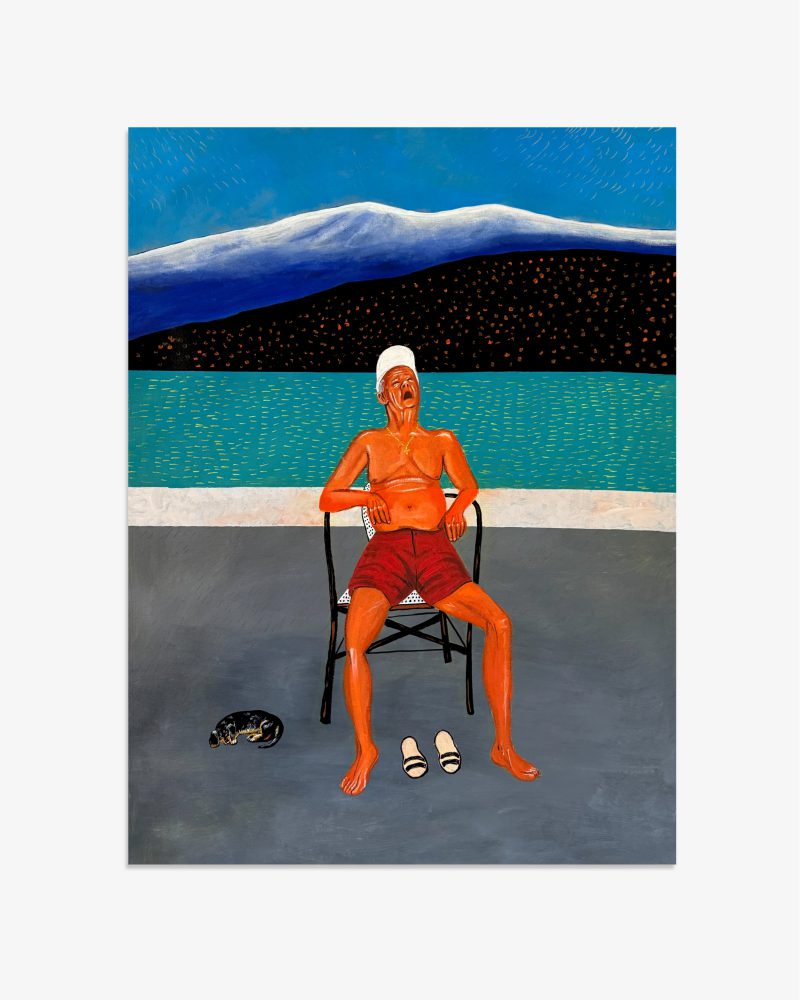

Born in 2000 in Beirut, Lebanon, Elie Chammaa is a multidisciplinary artist with backgrounds in graphic design and fashion. Although he’s engaged in art direction and graphic work, painting has always been at the core of his creative life. His style is primarily figurative and modern, with a subtle nod to post-impressionist influences. Elie’s work gently explores the intersection of identity, culture, and memory, using painting as a way to uncover and express the deeper layers of his own experience.

Athena Kuang: You were born in Beirut and are now based in Italy. How has moving between these two places shaped the way you see yourself and the way you paint?

Elie Chammaa: You know, it’s like having your heart and soul in two different places at once. I’ve built a life in Italy, but sometimes I feel a bit numb, like parts of me are scattered between the chaotic beauty of Lebanon and the more conventionally beautiful Italy. That in-between state pushed me to explore themes of identity, culture, and belonging in my work, because I’m constantly negotiating where I stand.

I romanticise the chaos of Lebanon; there’s something raw, generous, and deeply human about it. In Italy, it’s almost the opposite: everything carries this polished, classical idea of beauty. So my work ends up drawing from both. It’s a blend of what’s conventionally beautiful with something unfinished, slightly naive, or a bit unsettling.

Moving to Italy also made me grow very fast. You start out excited, then you slowly realise how deeply your home land is embedded in you, even the parts you once resented. And when something major happens back home, like a war, it sharpens that awareness even more. All of that inevitably finds its way into the work.

AK: Painting seems to sit at the emotional core of your multidisciplinary practice. What is it about painting that feels essential for you, even as you work across fashion, graphic design, and art direction?

EC: Well, painting is like this perfect fusion of everything I love. When I paint, I’m basically the art director of my own canvas. I’m thinking about the distribution of elements, the colour palette, all those visual choices. It’s like doing graphic design, art direction, and a bit of fashion sense all rolled into one. And I’m a photographer in that moment too, because I’m capturing a feeling or an emotion, almost like freezing a little piece of time on the canvas. It might be naive, it might not be perfect, but it’s all those skills coming together. So painting is really just where I get to put all those creative muscles to work and let them play.

AK: As a queer artist, you’ve spoken about feeling like an outsider in different contexts. How does this sense of displacement translate into your figures and compositions?

EC: Yeah, so it’s interesting. I always feel like an outsider, whether I’m in Lebanon or Italy, and even within my own queer community sometimes. In Lebanon, I might be seen as too different, too outspoken, not fitting the cultural norms. In Italy, I’m that guy from the Middle East with all the baggage that comes with it. And even as a queer person, I feel like an outsider because I’m in a culture that often moves so fast, stays on the surface, and I crave depth. I want meaning in everything; in relationships, in life experiences, and that can make me feel a bit too intense for the crowd sometimes.

So that sense of being an outsider definitely comes through in my art. My figures are often solitary, kind of living in their own bubble, and the space around them can feel a bit empty or void. I think it’s my way of showing that I’ve built this protective shield around myself, a little distance from others. And yeah, I’m working on breaking that down, but it’s a process. So all of that uniqueness, that intensity, that feeling of being on the outside, it’s all there in the compositions and the solitary figures I paint.

AK: Do you see your paintings as self-portraits, even when the figures aren’t explicitly you?

EC: Yeah, absolutely. I met this oil painter not too long ago who said something that really stuck with me, basically that all your work is a self-portrait, whether you realise it or not, because it’s a reflection of your subconscious. And I think that’s true. I wouldn’t paint something I don’t like or something that doesn’t mean something to me. Each painting is like a little piece of a puzzle, a piece of my story, sometimes literally, sometimes in a more subliminal way. So yeah, I’d definitely say my paintings are self-portraits. They tell my story, and I hope the people who really get it can see that. Even if it’s a bit of a puzzle sometimes, for those who look closely, they’ll find those pieces of me in there.

AK: Looking at your recent body of work, what questions are you currently asking yourself, and what do you hope viewers might ask in return?

EC: Oh, there are tons of questions swirling around in my head right now. I mean, the first big question I’m always asking is: am I understood? Do people actually like what I’m doing? Because as much as I might say I don’t care, of course I care. And I’ve been shifting directions a bit in the last six or seven months, and I’m wondering if this new direction is the right one. Like, is this the path that’s going to help me actually make a living as an artist? Did I find the glitch in the system, so to speak, or am I just chasing something that’s going to shift again?

Because the art world is tricky. People see the successful ones selling paintings for thousands, but they don’t see the struggle. And I don’t want to be that artist who only gets appreciated after I’m gone. I’m trying to figure out how to break that cycle and get noticed now, in a world where algorithms and quick hits and thirst traps seem to get more attention than art.

So I’m asking myself all these existential questions, like, how do I balance who I am with what people want? And on a day-to-day level, sure, I’m asking if a brushstroke is right or if the composition works.

I welcome all kinds of questions from the viewers, as long as they come from a place of care, curiosity, and kindness. It’s like being a teacher: you want your students to ask the smart questions, the ones that show they’re invested and really thinking about what you’re doing. I’d love to be challenged by my viewers, to have them dig a little deeper rather than just skimming the surface. Of course, I’ll answer any question, but the ones that really make me think or show that someone’s engaged, those are the ones I appreciate the most. So I hope people ask the challenging stuff. It means they’re really connecting with the work.