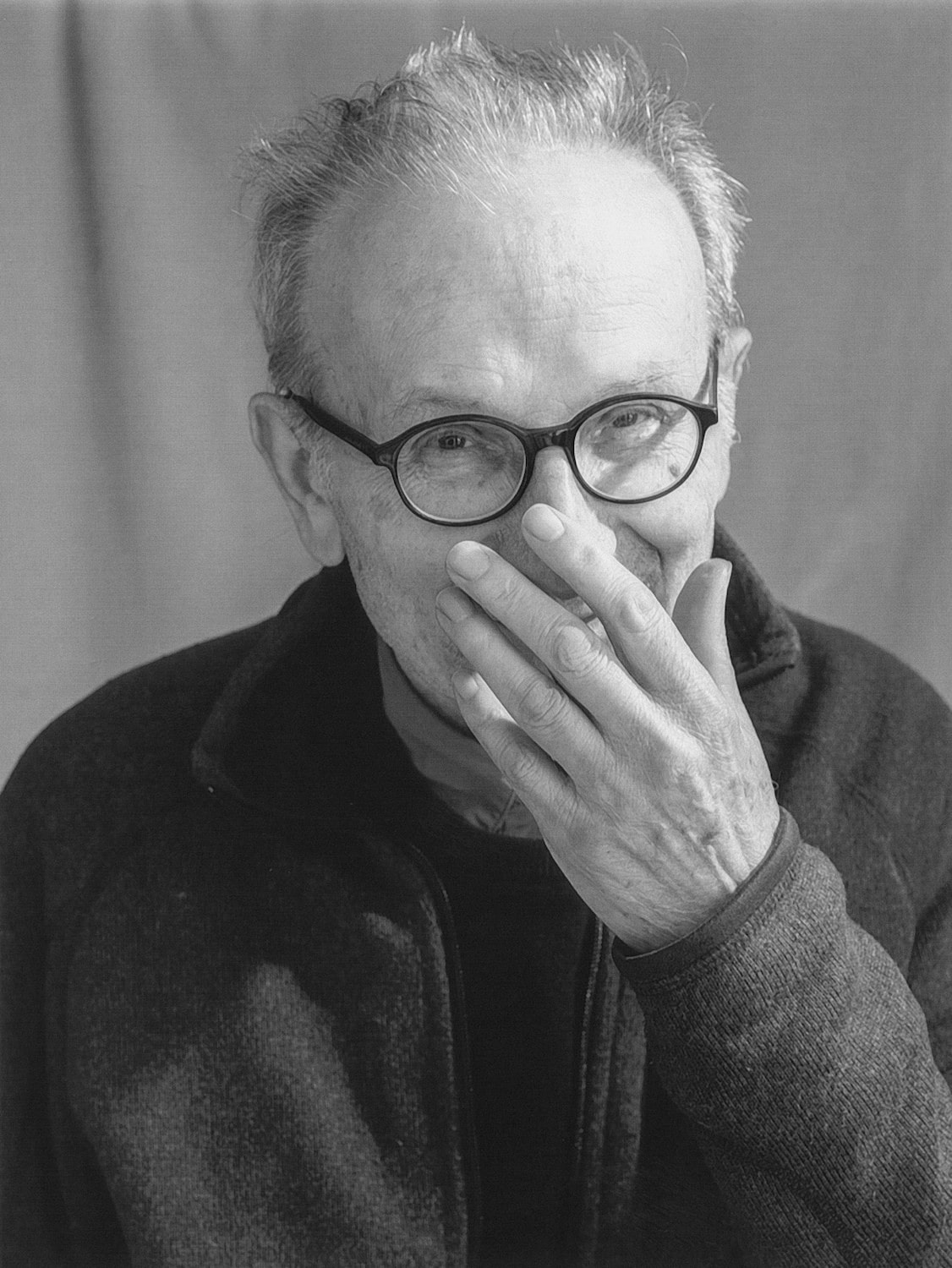

Seeing rather than documenting, appreciating intractable reality, looking to the margins, traversing the landscape, staying outside the city centre to inhabit the periphery, getting up in the morning to meet the sun: not only is Guido Guidi the photographer who transforms things into landscapes, but also the maestro that everyone dreams of meeting. I did it for you.

Guido Guidi: I hear you’ll be torturing me for an hour.

Rossana Ciocca: It’s meant to be a friendly chat, do raise your hand if you feel tortured at any point. You are considered a master of Italian landscape photography and your work has created dialogue with the world for many years, aimed at investigating the very practice of looking. May I ask what landscape means to you?

GG: I will answer with the words of Andrea Zanzotto. His father was a painter and he saw him as though he were wearing a landscape—a landscape cloak.

RC: It’s immersive then, we are all part of the landscape.

GG: What came first, landscape or landscape painting? I don’t know… Longhi would say that landscape painting came first.

RC: Your work has always focused on the marginal and anti-spectacular spaces of the Italian landscape, a cultural context that is diametrically opposed to the classic nineteenth-century vision of the landscape, or what we might call panorama. What is an image for Guido Guidi?

GG: It’s not a panorama. There is a tendency today to call everything “image”—understood as an incorporeal figuration. I don’t know if I totally agree, a figure has a body. With the advent of digital, mobile phones, and so on, everything has become an image, an image of reality—intractable reality—but photography is not just an image, it is also a photograph: a two-dimensional object.

RC: It’s also a creation.

GG: Yes, but let’s avoid the term “creative”, because there is only one Creator, the Eternal Father.

RC: You have been extremely committed to education and teaching alongside your professional career: since 1986 you have held workshops, lectures, and seminars in various Italian universities, including IUAV in Venice, Milan’s Politecnico, the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy at the universities of Venice, Lecce, Bari and the Cattolica in Milan, as well as various Italian public and private institutions. In one interview, I heard you say that schools should educate the eyes but that they don’t teach you to look and nobody looks anymore because we are all in a hurry. In your opinion, what kind of impact will not knowing how to look at the world have on future generations?

GG: Not knowing how to look is serious, at least that’s my opinion. In the 1920s, Lázlo Moholy Nagy observed that those who ignore photography will be illiterate in the future. Illiteracy is very convenient for authoritarian regimes. In Italy, we live in a sort of reiterated illiteracy, especially as regards photography. We have already fallen behind: not knowing photography today means being illiterate.

RC: Are you referring more to the historical, artistic, or technical part of photography?

GG: Unfortunately, almost nobody knows the history of photography. What interests me above all is knowing how to look, I am interested in learning to see, to understand; Minor White used to say that to understand a photograph, you needed to be sharp enough to cut yourself. Unfortunately, many photographers aspire solely to break into the art world, perhaps with good reason but at the risk of being tamed as Barthes says.

RC: I know you asked for a camera when you were very young, what advice can we give to parents who want to teach their children about photography and gaze today? Is giving them a camera enough? How do you educate the gaze?

GG: Photography is not taught but learned. One day on Calle dei due Bari in Venice, I happened to hear a mother addressing her son as he left the house: “Walk straight ahead and don’t stop and look”. This is definitely no good way to educate a child who must at least be taught to look right and left before crossing the road. Reality must be read, photography must be read: how can you take a photograph if you haven’t learned to read with your eyes? How can you be a writer if you can’t read? How do you learn to read a book? We try and try again: this is an A, this is a B, this is a sign. Teaching photography is more complicated because the visual lesson shouldn’t really be taught verbally. It has its own rules: visual rules. Cartier Bresson also lamented that we are not taught to look. We look at images fast and furiously, we look at the subject but not at how the subject is portrayed or their transformation. Lèvi-Strauss said that a painting “is not primarily what it represents, but what it transforms” and it is this transformation of reality that ought to be studied at school, especially the transformation that occurs through photography.

RC: I heard you say in an interview that photography is small…

GG: It is humble, first and foremost. “I am tired of shooting skyscrapers”, said Ralph Steiner, “I want to take photographs that are like ex votos”. An ex voto cannot be big. A few days ago, I read in the new book by Roberta Valtorta (Chiedi alla fotografia) that her students say that photography should be big because going to an exhibition should be an emotional journey. But emotion doesn’t require size. Communication comes from size, if anything, not emotion. Kierkegaard said that everything is focused on comprehension and nothing on ostentation. Sadly it’s a widespread phenomenon.

RC: In many of your photographs, such as the Fiume series, the practice of walking the same paths and getting to know the land around your house, looking beyond the threshold, has made you not only a great master of the mental processes needed to create space and time in your works but also a great pioneer in terms of the vital responsibility we all have to care for our own territories.

GG: Care is loving vigilance; a vigilance similar to what Ronald Barthes mentioned in his open letter to Michelangelo Antonioni. The letter was published in the Cahiers du Cinéma many years ago. Barthes said that one of the three virtues of the artist was looking after things. A little like that apprehensive vigilance a mother might have for a reckless child.

RC: Giving dignity to things, giving them a presence, thinking of photography as an act of interrogation, walking 100 metres as a pilgrim and not a tourist… I have often read that taking a photograph is a devout act for you, akin to praying. Could you explain how you come into contact with the things of the world? And while your work does not prioritise beauty, it is clear that it prioritises a gaze. How did you form this type of gaze?

GG: The devout act is no more…Carlo Scarpa used to say that it’s not about the ugly or the beautiful but the necessary. The signs you leave should not aim to be ugly or beautiful but necessary. Necessary for what? Like a tree with its branches reaching up to the sun: it’s necessary for them to turn that way, not in search of beauty but out of need. In terms of the devout act, I want to quote for the hundredth time Fra Angelico, as described by Vasari: “It was his habit never to retouch or alter any of his paintings, but to leave them as they came the first time, believing, as he said, that such was the will of God. Some say he would never take up his pencil until he had first made supplication, and he never made a crucifix but he was bathed in tears.” My practice goes hand in hand with his.

RC: You are very certain of this practice. May I ask whether it is spiritual or technical?

GG: I am only certain of the need to keep taking photographs. I do not, however, cry when I take them.

RC: No, of course not, but it is an extremely profound approach.

GG: I remember once during a public conference when the semiologist Paolo Fabbri asked me if I had ever cried in front of a painting. He did it to provoke me. I confessed with both shame and certainty. When I was a student in Venice, instead of going to my mathematical analysis lessons, I would often go to the Correr or the Accademia… There is a little room there, where you can find anyone from Giorgione to Giovanni Bellini to Piero della Francesca. But just as you go in, there is Andrea Mantegna’s Saint George. I cried there. Why? I can no longer remember, perhaps moved by the quality of the painting. I do remember that an English man approached to ask if I was alright and I reassured him I was.

RC: I can relate, for me it was Piero della Francesca’s Madonna del Parto. I would like to show you one of your photographs that particularly moved me: Ritratto a Maurizio Predasso con e senza barba, Italy, Venice, 1974. In this photo, you depict the same subject (Maurizio) two times, with and without a beard. The artifice is extremely simple but terribly powerful. Maurizio is clutching a photograph of himself (without a beard) that looks almost luminescent, like an annunciation. Could you tell me about this photograph?

GG: I struggle to talk in general, let alone about my photographs… We were living in Venice, Maurizio and I, in a sort of commune of architects and painters. I was already a photography maniac and I photographed everything I came across. Maurizio was telling me that he had to take a new photograph for his passport because his beard had grown in the meantime, so I took this photo to somehow remember the time. It certainly wasn’t suitable for his passport. Perhaps Giorgione is the painter who has worked most insistently on the idea of time. In the room next to Mantegna’s Saint George at the Accademia is a portrait of an elderly lady holding a scroll with the words “with time” on it, an allusion to “with time I became old”. The title of this painting is The Old Woman, which is unfortunate, if only because the title is already there on the scroll. I believe it was Salvatore Settis who suggested that it was probably the client who asked Giorgione to clarify the meaning behind the painting because it was too hermetic without the scroll. There are other signs that refer to time in the painting but the client wanted a linguistic underlining of the theme, a set of instructions almost. The scroll does, in fact, look a little artificial.

RC: It’s a small piece of parchment, isn’t it?

GG: Yes, but the structure of the parchment, like the collar of her chemise as it happens, is S-shaped. A softer variant of the Z, which is the arrow of time.

RC: This photo of Maurizio is one of my favourite of all time. Do you remember the introduction to Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography? When Barthes is talking about the Emperor and those little “touches of solitude”. It’s like that.

GG: I’m glad you like it. I remember it was taken with a wide-angle lens.

RC: The room looks like something out of the 16th century. The first thing you notice is time, which almost always appears in your work, but this image is almost unreal in its sheer simplicity. A person holding a photograph of themselves (but different) is a simple artifice but it is the combination of poetics and composition that makes it.

GG: There are other photographs with people holding portraits but it’s usually mothers holding photos of the sons they have lost at war.

RC: I have brought another photograph with me so that we can chat more about the images. I really like it. If I lived a little closer, I would come and bother you more often.

GG: Which photograph?

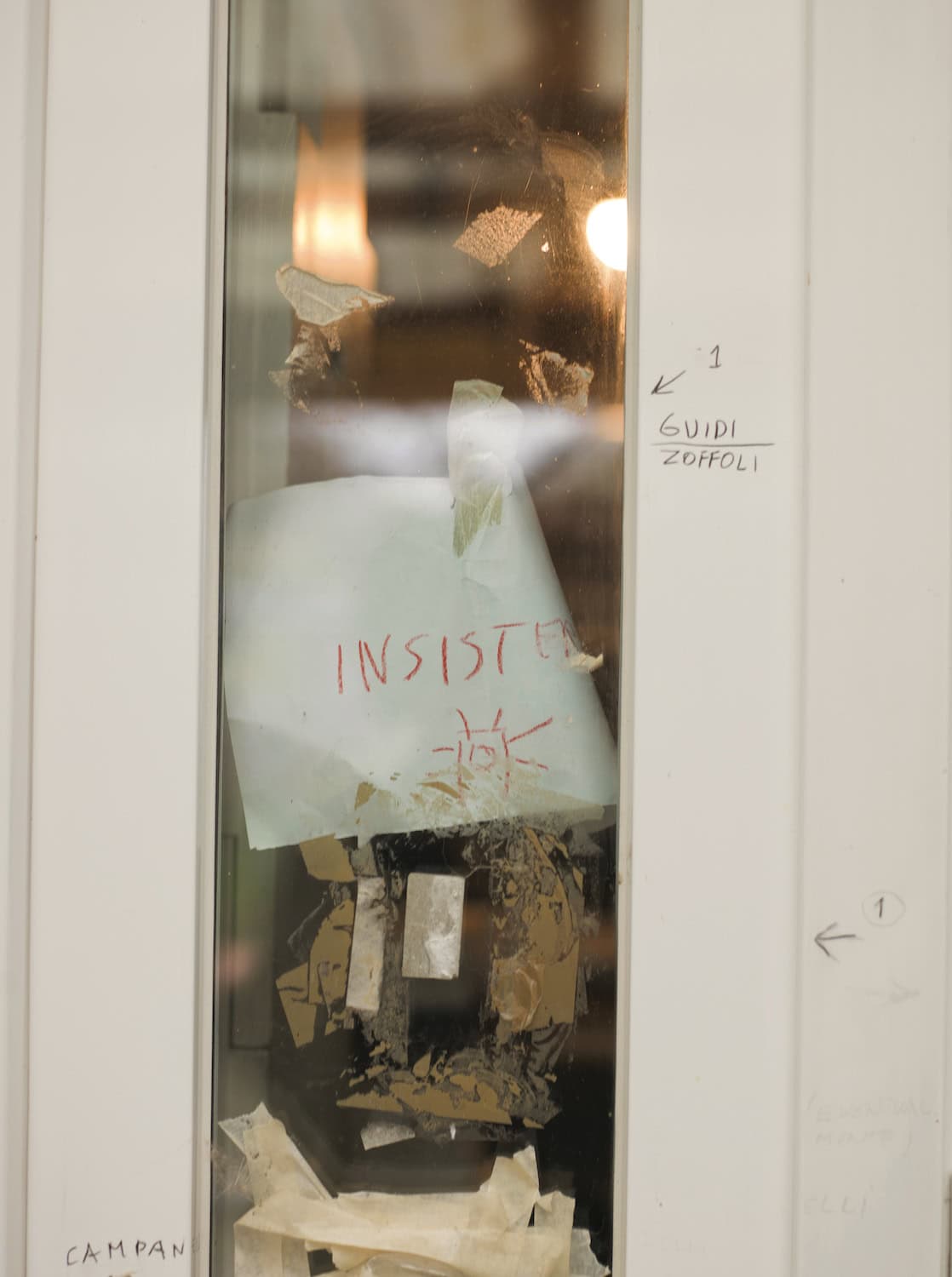

RC: The photographs is classified as specchio o vetro, Misinto, 1997. It’s covered in tape. It doesn’t look like a mirror to me but the back of something.

GG: Where did you dig this out from? I don’t remember it.

RC: Is it a mirror? Or a window? What is it?

GG: It’s a window, I assume, of a phone booth, from behind.

RC: I knew it was the back of something.

GG: The subject is definitely a phone booth window.

RC: All your work is defined by this attention to fragments: sometimes written words, sometimes cracks in the wall, sometimes open doors. All these images manifest as traces or signs. I find that your photographs create spaces and places in which to reflect, as though photography was defined by an absence, and the gaze of the spectator completes it. For example, when I look at this photograph, I cannot say that I am truly interested in the representation of the object as much as in the silent powers that it brings into play. I find that some of your work, like that of other photographers such as Lewis Baltz, is similar to conceptual art. What do you make of this statement?

GG: Conceptual art… Many years ago in Arles, I met Jean Claude Lemagny, director of the photography department at the Bibliothèque Nationale. I showed him some photos—I was still young—and he called them naïve conceptualism.

RC: Why naïve?

GG: Then he added: “It is a very rare quality.” I’ve been proud of this ever since, perhaps I’m conceptual in spite of myself. I have never taken photographs that require an explanation or instructions. Contemporary conceptualism is very much in that vein, starting with Duchampism. I have taught for many years and I am familiar with this neo-academism.

RC: Would like to discuss this idea of the gaze further, precisely because you don’t explain, you don’t define the things you photograph and your photos are places in which the spectator can think, seek, and ask themself questions. I think that this approach is typical of our reading of some conceptual work, which somehow allows interpretation of the other while maintaining an extremely distinctive style.

GG: Beyond the visual.

RC: Yes, it is an opening of the gaze, beyond the photographer. This image [the phone booth window], for example, can be many things because it is composed of fragments. For one person, it might be an abstract painting, for another a map… Depending on the gaze and sensibility of the viewer, all these fragments can open universes. And I don’t mean that the surface is composed of fragments, but of signs, a word you often use.

GG: Yes, I understand, but the thing is that this idea of seeing other things within reality and photography has a name: pareidolia. A doctor from the Salpètriere Hospital performed an experiment: he showed photographs to a patient. They were photos of a mountain with donkeys climbing on it. He told the patient that this photograph depicted her naked and she got extremely angry and tore up the photo. A copy of the same photograph was mixed among others but when it emerged once more, she again became incensed.

RC: A little like Dali.

GG: Daniel Arasse said: “The prestige of the image consisted and still consists in the ability to confuse what texts and a clear conscience wish to distinguish.” Years ago, I went to the Correr in Venice to see a Jim Dine exhibition, a tribute to Morandi. At the entrance was a large painting of approximately 2×4 metres. Morandi? What’s on earth? Fine, there were some bottles in the painting but that’s not enough. There was a skull too and Morandi never painted a skull as far as I know, although he loved Cezanne who did include them in his still lifes. So what’s the connection? I looked at Morandi again and I finally saw where I was supposed to be looking. I should have been looking in the cracks, between one bottle and the next.

RC: But looking is a very complicated theme, Guido. It’s a pure practice and asking questions such as yours about the skull is the only way we can force ourselves to look.

GG: Yes, I agree.

RC: It’s very difficult to teach, as we said.

GG: Because it risks becoming too obvious.

RC: You have often said that your photography practice develops from the margins and not the central perspective of the image. I read a great essay on Picasso by David Hockney years ago in which he declared that Picasso was the first artist to have truly overcome the centrality of the image and not solely at a theoretical and practical level but sociocultural too. According to Hockney, Picasso abandoned the centrality of the space because he wanted to move past catholic iconography; he shifted from the centre to culturally move away from the central axis of the crucifix and therefore the passion and suffering of man. What does looking at the margins, at the perimeter, mean to you? What does it mean to be a vernacular photographer?

GG: I like the word vernacular. The margins… A long while ago, I read something by John Szarkowski in which he observed that Vermeer’s paintings didn’t start from the middle but from the sides. Vermeer broke with Roman centrality and this method meant: 1) that he almost certainly used a camera obscura; 2) this new tool changed the way we portray and see things.

RC: We were born and raised with that central vision, we are permeated by the central perspective. Our buildings, frescoes, and churches—everything takes us there, which is why I think it’s such a complicated exercise to move away from the centre.

GG: Yes, you’re right, but we must remember that in De Pictura, L. B. Albertini proposes the horizon at eye level and the vanishing point “wherever you want” and Angelico put it outside the painting. We should also remember that Perspective is the ancestor to Photography and yet the tourists all flock to the city centre, all the exhibitions are held in the centre. Pietrantoni said that in ancient sacred paintings, you have the Madonna in the centre, the Saints alongside her and then little angels the further you get from the centre, frolicking in the margins of the paintings.

RC: If I imagine an exhibition of your work, I cannot imagine it with a classic, horizontal set-up. I would see it more as an expanding universe.

GG: Fausto Melotti said there may be motorways but there are also pathways and we should walk them all, perhaps with a vague sense of guilt.

RC: I like your total coherence when it comes to photography so I wondered if you had ever organised a less institutional exhibition.

GG: I used to like organising exhibitions, but I get tired now and prefer sitting at a table, prepping a book perhaps. The first show I held was back in 1968, I remember gluing the photographs to plywood panels with Vinavil and then arranging the panels, but I actually don’t think displaying photos on the walls is the best way. Better on the table or like that show where I arranged the photos to build sequences.

RC: If I’m not wrong, you quoted Seneca in a public interview: “Give your eyes time to unlearn”.

GG: Ah, beautiful, I quoted that?

RC: I’ll read you the whole thing. After the Seneca quote, you say that we must be eternal learners, that we must unlearn in order to come back and look again because we must constantly refresh our gaze on things and today’s fast-paced world doesn’t allow it. Listening to this phrase, it occurs to me that you are using the time you are taking to look again and renew your gaze.

GG: Are you going to include that in the text?

RC: Absolutely. I am particularly interested in this topic because the image nowadays seems to be more important than in any other age (thanks to social media, of course), but it is always the same.

GG: To this point, I would like to mention Percepire le differenze, a piece but the late Paolo Costantini for Fotologia magazine.

RC: The algorithm rewards images that are the same so we are unlearning how to look more than ever, in favour of images that are increasingly identical.

GG: We like to be comforted, to know that nothing is changing.

RC: The slow pace you are implementing in your reading of the photographs of these past 50 years is certainly not fashionable, but I think it’s the only conceivable way to re-examine your entire journey.

GG: Absolutely.

RC: Thinking, for example, of all the projects you were assigned in the 1980s when they called you to participate in research projects for the transformation of the city and territory. I remember one for the Archivio dello Spazio project by the Province of Milan, as well as your work on public housing for the INA-Casa project, and the Italian Atlas, curated by the Directorate General for Contemporary Architecture and Art. Between 1993 and 1996, you documented the new urbanisation developing along the ancient road axis between Russia and Santiago de Compostela after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Today, after this lengthy investigation into the Italian territory, what are your thoughts on the urban changes of recent years and the major transformations in urban and suburban areas? What kind of gaze have we lost in the last fifty years?

GG: What do you mean by that?

RC: What have we lost that used to be present in your photographs? Have the suburbs remained the same?

GG: I can no longer work in the suburbs. The houses all have a nice “jacket” on (thanks to energy saving laws) and have been repainted, highlighting an architectural vulgarity that was previously diluted by wear.

RC: The Villa dei Sogni (Villa of Dreams) has gone. That was another of your photographs that I have always loved.

GG: The Villa dei Sogni was demolished years ago and they even burned the pine forest that surrounded it. I’ve lost my energy and enthusiasm along the way: I have too many things waiting to be photographed and I find this discouraging. I walk and I don’t go back to the places I had planned to go back to; I no longer have the strength to stop, or to neglect the people waiting for me at home.

RC: That’s lovely.

GG: Not exactly.

RC: Well, it can be interpreted in two ways.

GG: I hope that this desire to stop and waste time with something I find along the way will return with the spring.

RC: I am interested in sustainability, for work of course. How much time do you devote to territorial projects, such as the Fiume series for example.

GG: That took four months while In Between Cities, for example, took 15 days in August for 4 years. It was a one-way journey, which is something I do sometimes. I have a project in the works with Michael Mack, Andata e Ritorno, a series of photographs taken in the seventies from my R4 while I was driving along the Via Romea from Cesena to Venice and back again. These projects came about primarily because I wanted to go and see what was out there, to wake up in the morning and have these extraordinary experiences, to meet the sun, the light, houses, whatever was out there… “Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet” is the caption to a Courbet painting that shows the painter wearing a backpack of tools and coming across two people who greet him.

RC: You go to meet the landscape.

GG: Exactly! I went into the bar on Ca’ Tron for a coffee one day and Marco Venturi was there having a coffee too. I said, “Marco, why don’t we take a trip like the one Vittorini dal Piemonte took down to Sicily?” Marco sipped his coffee and then said we should take a trip across Europe and we left just like that. The initial idea was to see what was left of the B1, the road that Napoleon wanted to connect Paris to St Petersburg.

RC: Because traversing the landscape is crucial to understanding it.

GG: Yes. We went through all these villages along the way, always outside the city centre, almost always in the suburbs.

RC: Because the suburbs are the margin.

GG: City centres are too stiff and plastered. The outskirts are always moving and transforming. For the record, since the first part of our trip went so well, it occurred to us to extend it to Santiago de Compostela. Our journey through Spain was one of the best parts.

RC: Why is that?

GG: The sunshine, the food, everything.

RC: I am being told that it’s time to say goodbye.

GG: Robert Adams tells us that Timothy H. O’Sullivan greatly enjoyed photographing in the desert, despite the mosquitoes…See you in Cesena.