It’s February and the 8:30 am chill on the Montisola coast freezes your bones, while the stillness makes you feel at one with the rest of the world. We’re here to meet the family behind Horto, the much anticipated restaurant opening this summer in the heart of Milan. We meet producers Camilla, Matteo and Tommaso from Orti Iside and father-son fishing team Fernando and Andrea. Later in the day, we are also introduced to Norbert Niederkofler, the sustainable Michelin star chef, and the Horto team, Stefano Ferraro and Alberto Toé. They’ve missed the ferry from Sale Marasino (or, I fear, we gave them the summer timetable) so they head over in a small fishing boat, the same way I imagine Clooney accesses his Cernobbio residence. It’s a constant stream of contagious smiles and kindness; clearly Horto puts you in a good mood. If you haven’t heard, it’s going to be a locus amoenus in the centre of the city, a restaurant guided by a new philosophy that professes ethical time. Co-founder and executive director Diego Panizza took the name from Horti Conclusi, enchanting monastery spaces dedicated to the cultivation of rare plants, reflecting the harmonious reunification with the natural environment that it intends to embody.

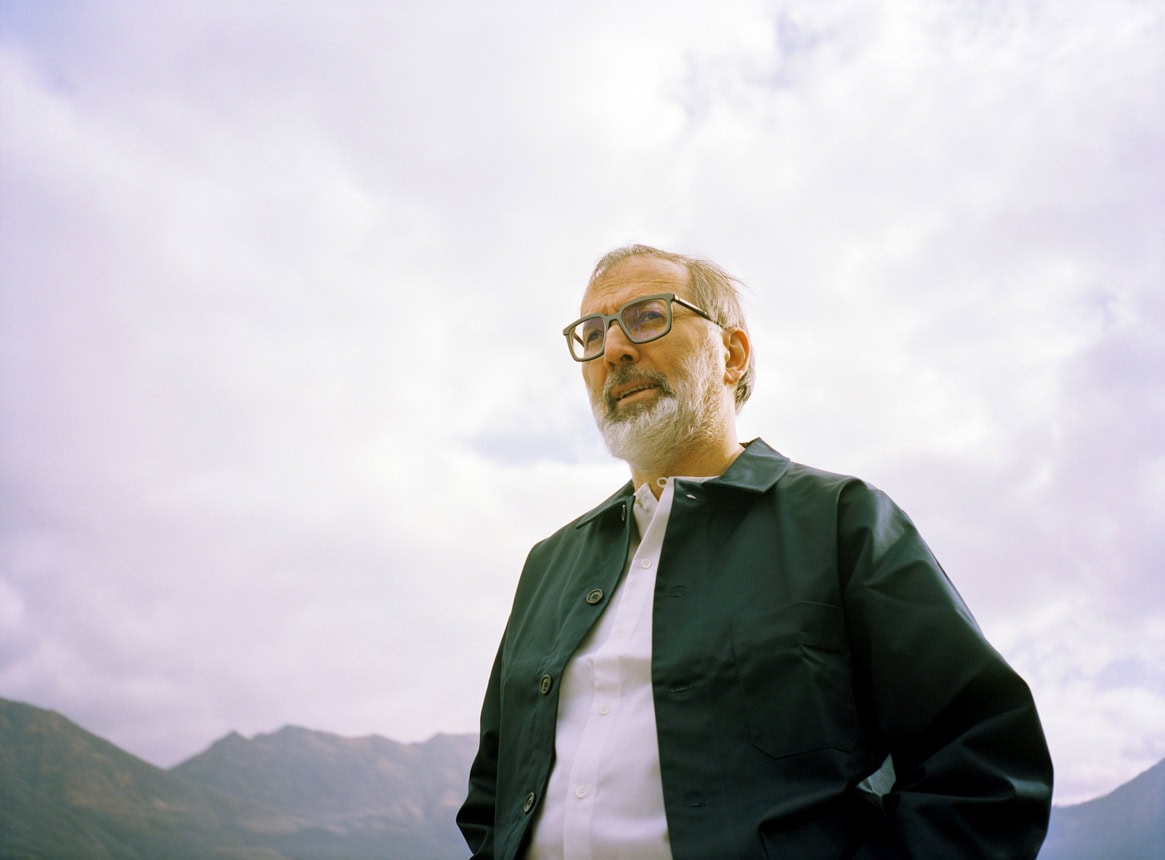

Niederkofler will be the head of strategy, leaning towards the sustainable and local sourcing of products and rediscovery of an authentic cuisine. What other reason would we have to wake up at 5 am other than to meet the people who will be making this project a reality? Retracing the journey of the food we eat, from roots to plate, is a precious opportunity and one we didn’t want to miss. “Horto is a huge opportunity to get our foot in the door in Milan with a project that reflects our philosophy and approach,” explains Niederkofler. We are sitting at Locanda al Lago, the restaurant run by the fisherman’s family. It’s 12:30 and we are right over the water, waiting to be fed. “It is a project for the future and for the generations to come that professes a sustainable way of thinking. And it’s not just limited to food, but to architecture and lifestyle too, and that’s what we like: it’s a decision to be ethical.” So what sort of things are they planning? “Stefano, Alberto and I didn’t want trucks travelling across Italy, so instead we just decided to draw a circle around Milan that wouldn’t extend further than an hour and a half away. Even in that short distance you can find everything you need. Just look at this.” And to illustrate his point, he flings his arms open to the expanse of lake before us. “We need to change our way of thinking. If we perpetuate current rhythms, we’ll hardly have any crops left. To be honest, I’ll manage just fine because I’m sixty years old already, but the problem will fall to the younger generations. I have two children so I have to think that way. It’s not always and exclusively about me, it involves thinking about the future, in general. Thinking about diversity and respect for producers and nature so that our children can live. Our work has proved to young people that if you respect the nature around you, you can access all the materials you want and earn three Michelin stars. And the same applies to any region in Italy. They all have so much to offer; Lombardy, with its vineyards, lakes and freshwater fish, mountains and unique rice cultivation, has everything. Systems like Horto will protect nature, traditions and culture.” In light of this, what the new restaurant will offer its guests is a chance to be reintroduced “to all the wealth, culture and materials the region has to offer, without leaving the city centre.” And what about the Horto family? “We’ve reversed the system: it’s not the chef and their team in the front row, it’s nature. Then you have the producers, such as the farmers and fishers; they are the ones who make it possible for us to work with extraordinary products, so their contribution is vital.” Orti Iside will supply all the vegetables. They have six acres of fields with plans for modernisation, including aquaponic systems and new innovative crops of fish and mushrooms. The young, incredibly healthy looking and enthusiastic team is composed of linguists, engineers and architects, all working together to establish a structure that enhances local wealth. The humorous, welcoming and amiable fishers, Fernando and his son Andrea, are continuing the family business that Andrea’s great-grandfather started. They originally opened the restaurant to use the fish they were catching first-hand and focus their efforts on collaborating with partners that appreciate unique raw materials. “It’s not about me, we’re not built that way; we’re only the third row,” Niederkofler continues. “This means acting ethically and respectfully towards all those involved.” And what does ethics mean to Niederkofler? “Ethics is simply respect for nature, for humans, for the family respect for anyone doing anything. Nothing more.” Horto was a pre-pandemic project and, like so much else, it was put on hold. Designing a social space during times of isolation sounds like a challenge. “I was in shock at the start of the pandemic. Our calendar just collapsed; my assistant Christof and I had plans to travel to Korea, Japan, and Mexico. And then I started meditating on this whole situation and the first thing I realised is that I have a family. Prior to the pandemic, I was never at home.

I have a beautiful relationship with my older son, Thomas, but it’s completely different with my youngest because I was there to put him to bed and wake him up for four months. To this day, it is one of the most important and cherished elements of this whole experience. I don’t want to be insensitive, because many have been terribly affected by these tough times, but it was the best period in terms of my family life.” Niederkofler has the great gift of being an optimist: “I am a person who always sees the glass half full, never empty. Every crisis holds enormous potential for reworking old systems. One might ask, ‘Why do I have to question them if they work?’ but you must. We still have a lot to pay but we’ve witnessed major changes, including a switch in the life-work balance, especially in younger generations. It’s important to start doing things differently. I’m used to working fifteen hours a day and I don’t want to do that anymore. Last year I turned sixty and I decided that I want to respect the rhythms of family life. I spent my first Christmas at home and I’m going on holiday with my family for ten days in Easter because Thomas has a school break; the other one doesn’t care, he’s in nursery.” And lucky him, may I add. During such turbulent times, it is beyond fascinating to study the trends in Google searches; for example, during lockdown we were looking less for “comfort food” and more “how to grow a vegetable patch at home,” in keeping with a general desire to better ourselves. “The worlds must be separated,” Niederkofler explains. “In Italy we have a vast culinary culture that we inherit from our grandparents and great-grandparents, so our focus and desire to better ourselves has increased and, of course, we cooked at home for three months. Convenience food has also increased, but price is not the key factor. The problem today is waste: 30-50% of food that is being bought is thrown away.” And for just a moment, the chef turns into an economist: “If you do the reverse calculation and decide to only buy what you will actually consume and increase your spending by 20% by purchasing from small producers, you’ve actually saved money and spent well. Of course, during the pandemic we had plenty of time to go shopping and were happy to do so every day, but I hope that we won’t go back to the old rhythms. New countries, such as China, will continue to act this way for a long time because they’re all ‘go go go’ and ‘grow grow grow,’ which is why I said we need to separate our worlds. It’s important for us to lend a hand because that is how you maintain a culture.” Generally speaking, we all studied and researched more during lockdown; but don’t be fooled, research is a double-edged blade. “You have to be careful on Google. We have young guys in the kitchen who just google a question instead of asking or looking for first-hand experience, and they believe everything they read. It’s important to maintain curiosity in making mistakes. When developing our philosophy, we had to close a few doors, using citrus fruits for example, which meant that we had to do our research; the saying ‘when one door shuts, another one opens’ becomes relevant here.”

The fisherman Andrea joins the table. “Oh good, now you’ll have to listen to all the ridiculous things I have to say,” the chef greets him. “Are you really sixty years old?” he replies. “I am and at this point I should probably start caring less. But I love my children and I want them to see the world and taste some real flavours. I don’t care if they want to become chefs, I am just here to help them develop and make their own way.” Niederkofler’s parents also worked in hospitality, “But I became a chef because it was the easiest option. I wanted to travel and I had no money, so I just chose a job that was located wherever I wanted to go on holiday. I’ve always done whatever I wanted in my life.” Well that doesn’t sound too bad. We are interrupted by a gentle voice that introduces a dish of dry sardines on a bed of dumplings and tomato sauce. Niederkofler has a special appreciation and understanding of life, one to admire and one that shines through in his kind, authentic and generous attitude. And in the midst of more fish and conversation, we miss our ferry back to Sale Marasino.