Hans Thyge Raunkjær, a renowned Danish designer, lives and works in Norsminde, Aarhus, where he leads his acclaimed design studio. After completing his studies at the Danish Design School in Copenhagen, he began his career as a set designer for the Danish theatre company Dueslaget before moving to Milan, where he collaborated with some of Italy’s most prominent designers. During this time, he honed a deep understanding of the art of visual storytelling – an element that now permeates all his creations.

His ability to intertwine cultural and historical references in his projects has made him a pioneer in conceiving design as a form of storytelling. In 1983, his talent took him to Milan, where he spent seven years working with leading figures of Italian design, including members of the renowned Memphis Group, the collective founded by Ettore Sottsass that revolutionised design and architecture in the 1980s. His return to Denmark in 1990 marked the beginning of his independent career, as he founded Hans Thyge & Co, shaping his vision of design focused on the exploration of furniture, objects, and interiors.

Today, Hans Thyge & Co is a benchmark for design excellence – a place where experience and innovation harmoniously merge, guided by a profound mastery of materials and production techniques. Raunkjær’s work remains a continuous dialogue between aesthetics, functionality, and the ability to evoke stories through every single creation.

Ritamorena Zotti: Your studio combines aesthetics and functionality with a strong narrative. What are the fundamental principles you follow in your design approach?

Hans Thyge: I started my career in theatre, and for this reason, storytelling has always been fundamental to me. Every object that surrounds human beings is full of stories. It could be something as simple as a fork which, through its material, shape, and craftsmanship, evokes cultural habits and different narratives. I often use the word “baggage” when talking about the history of an object. The designer works in that intermediate space between “baggage,” functionality (what it is used for), and the personal commentary we can add to make it relevant in our time.

RZ: In your studio, how do you face the challenge of innovating without losing the identity and emotional value of objects?

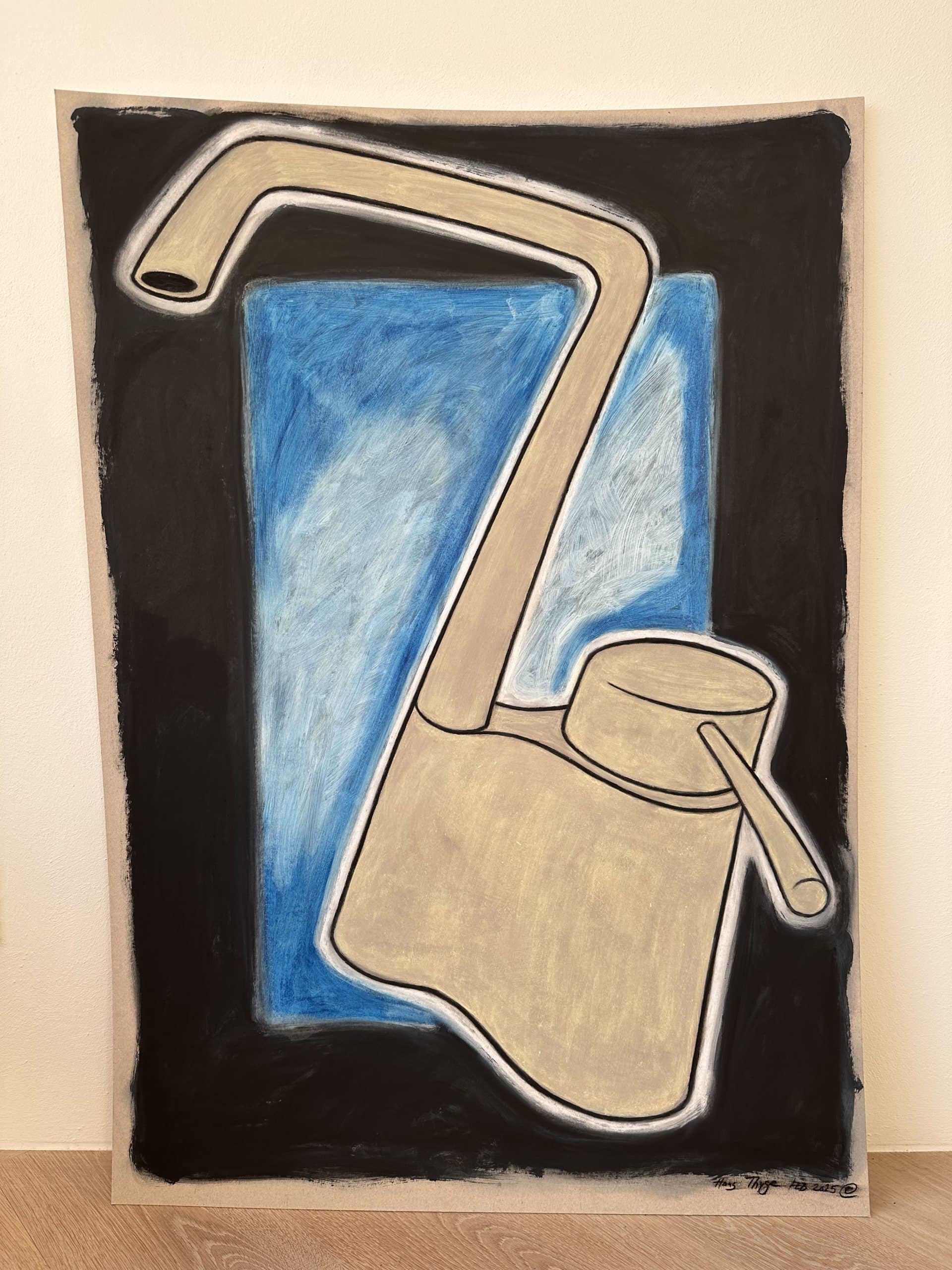

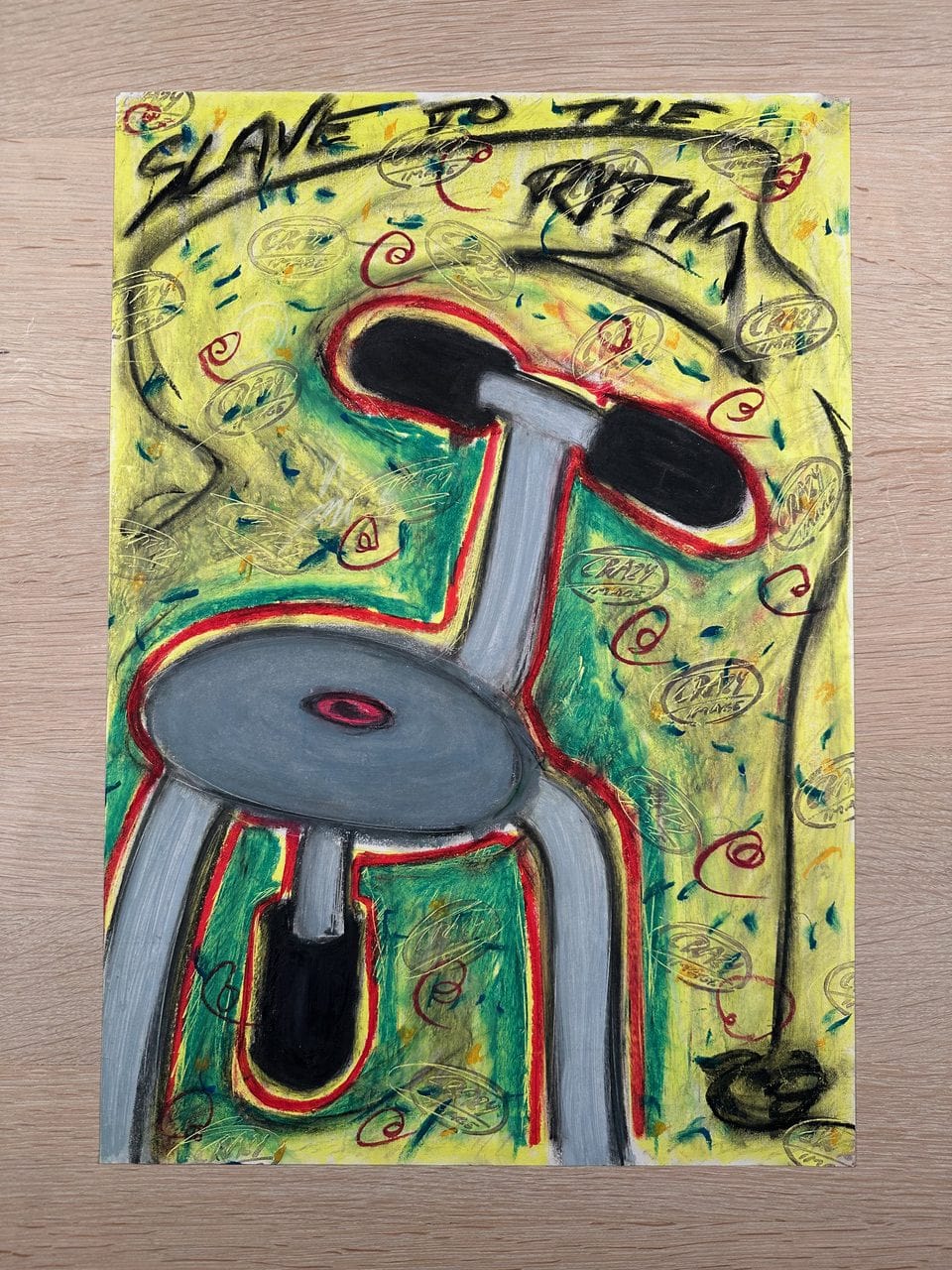

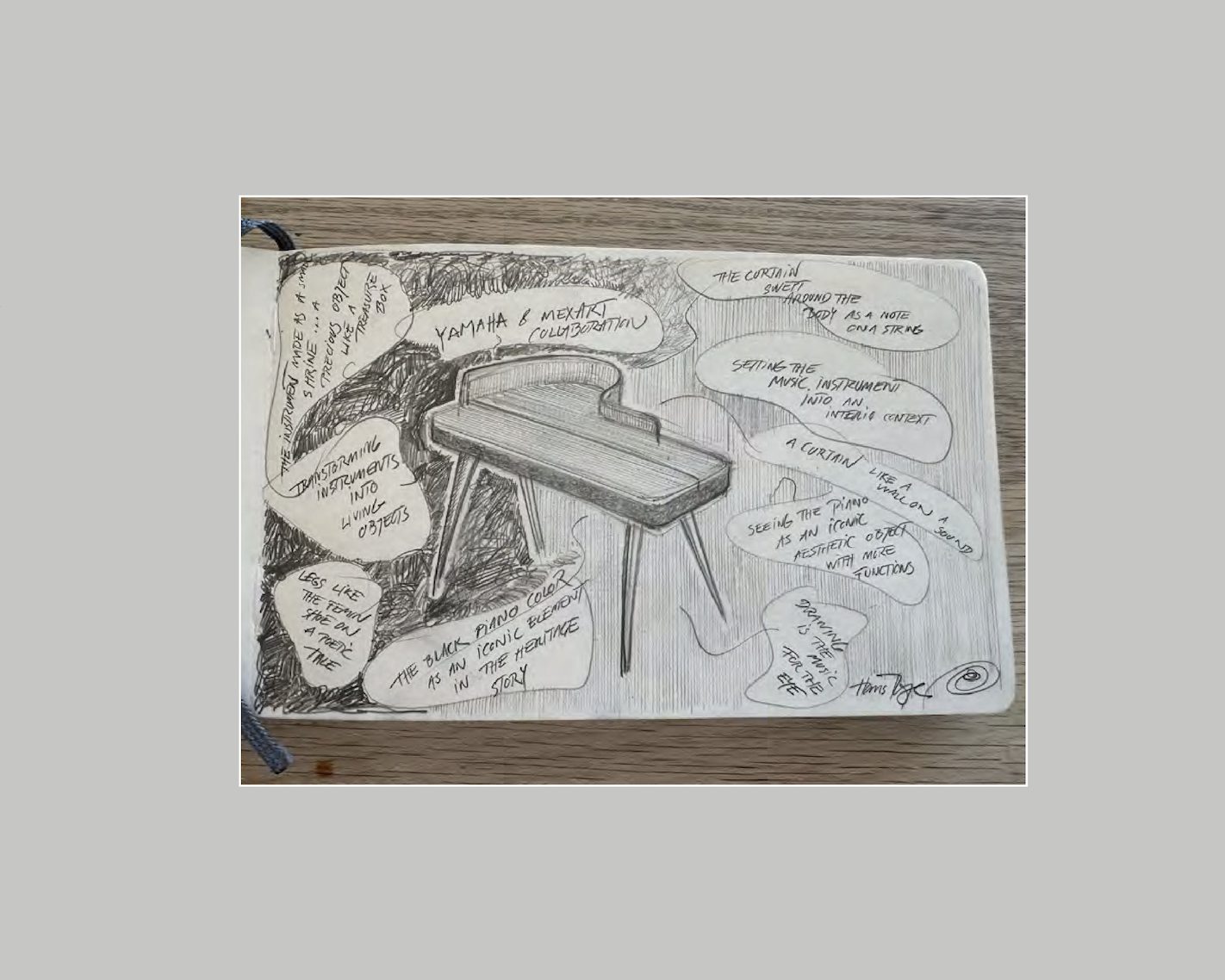

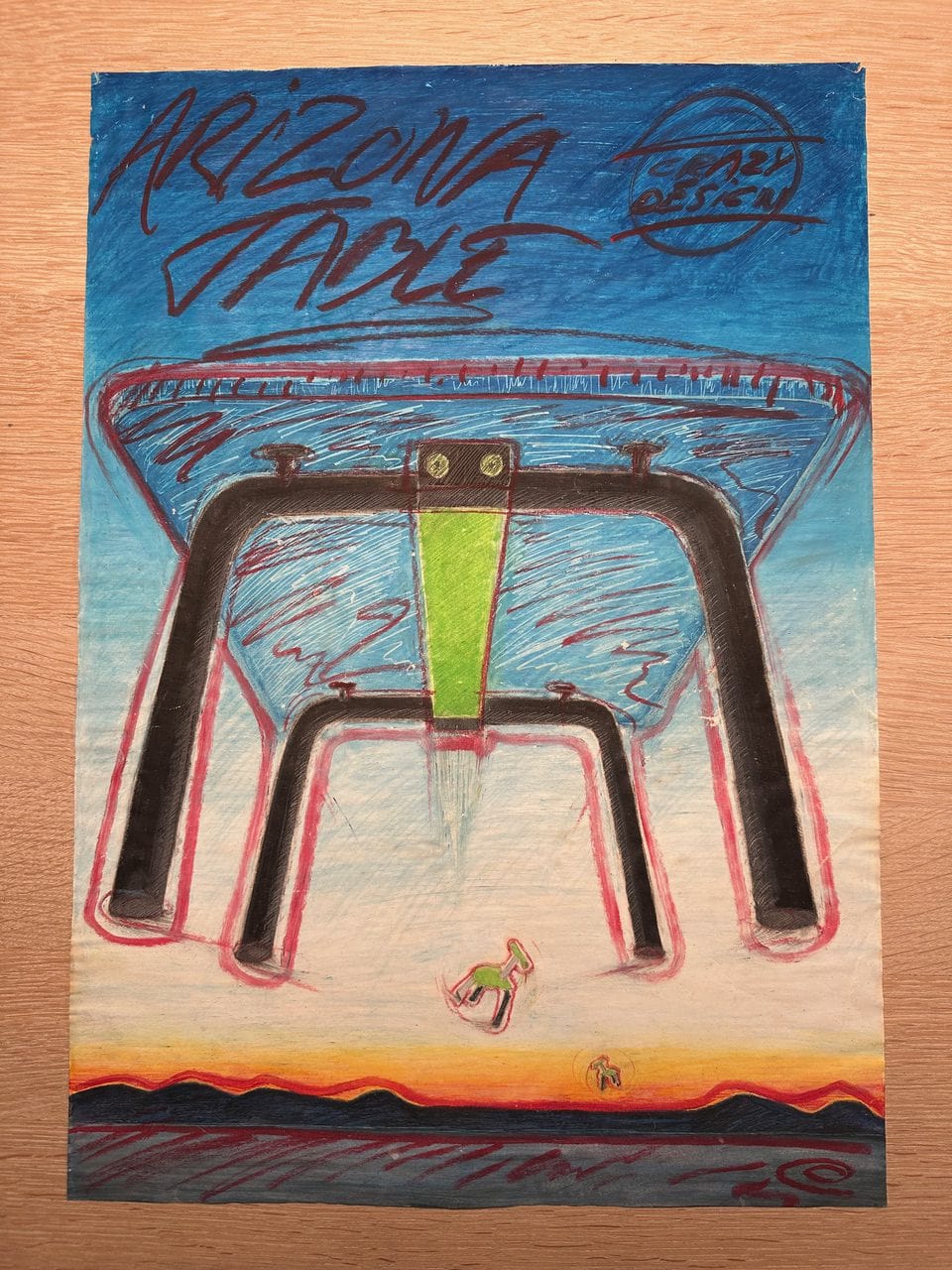

HT: In our studio, we work a lot with sketches, models, and paintings. We use them as tools to capture the spirit of an idea. Just like in cartoons, we experiment with abstract and exaggerated drawings because caricature often holds the essence of a concept. When you create the right sketch, you recognise it immediately, and you must preserve it like a recipe to follow in the creative process. It’s like a “magic cube” that holds the flavour and essence of the idea… or, to put it more poetically, it contains the dream. The Canadian painter Barry Lereng Wilmont once said – if I remember correctly – that a work of art is born in the dream, grows in ecstasy, and ends in the aura of defeat, because no work can ever reveal the dream in its entirety, only a glimmer of it. In our work, we must strive to define the dream, the feeling, and the thought that an object carries, keeping them alive until the final realisation.

RZ: Your studio also had a headquarters in Shanghai until 2019 and in Asia. How does this dual perspective affect your design approach?

HT: I have always travelled a lot, and in a globalised world, it is essential to be open to the cultural stimuli around us. Someone once said: to design is to know how to see. The designer lives in sensitivity. For us, it has always been natural to find inspiration anywhere, often in the places where we least expect it. The beauty of other cultures lies in the fact that they see aspects of life through different eyes, and this also makes you reflect on your own culture.

RZ: What experiences or collaborations have had a fundamental impact in shaping your vision of design?

HT: I wouldn’t know how to say precisely… Every project, client, or social collaboration teaches you something essential. Design is a complex discipline, and many projects never reach the consumer or have a very short life. It’s a bit like making a film: you can have the best actors, the perfect script, and even the best director, but if the cinematographer doesn’t capture the essence or if the location is wrong, the final result might not work. Sometimes, incredible projects are born with unknown and inexperienced clients simply because all the right elements align at that moment. Other times, a project succeeds magnificently because the client is extraordinary and has the courage to delve deep into the creative process together with the designer. I love design precisely for this unpredictability.

RZ: In the 80s, together with the Memphis Group in Milan, you shook the world of design with its radical and ironic approach. What do you think is the most important legacy of this movement for the new generations of designers?

HT: I lived in Milan from 1983 to 1990 and worked with George Sowden and Nathalie du Pasquier. It was a lightning-bolt experience. For me, Memphis represented a total opening of design to the world. Before, design had the task of solving problems; then, Sottsass arrived with a group of young people saying that design is expression, a dream, an accumulation of cultural stimuli. Design must speak to the senses, not just to rationality. Memphis freed design from stereotypes and invited consumers to laugh, reflect, touch, and be curious.

RZ: Memphis dared with bright colours, plastic materials, and irregular geometric shapes, breaking with modernist rationalism. Do you think contemporary design still has the courage to challenge conventions like back then?

HT: Not really. I think today’s design has become very mainstream. It seems that interior design has taken over everything, reducing design to a harmonious aesthetic that blends with the surrounding environment. I, on the other hand, see design as a language that thrives on chaos and disorder, mixing beauty and ugliness, new and old, minimalism and brutality. Design works when an object moves you so much that you want to buy it, regardless of where you’ll put it.

RZ: Sottsass saw design as a poetic and sensory expression, not just functional. How do you manage to integrate poetry and emotionality into design while maintaining functionality?

HT: Lately, we have resumed painting and using sketches as an additional material for the product. I strongly believe in storytelling through videos, words, and drawings. A beautiful object is one that continues to reveal new aspects over time.

RZ: In a context where design is increasingly influenced by marketing and business strategies, how do you see the role of design as a means of communication and cultural change?

HT: Design is sculpture, tactility, emotion. Only by treating it as an expressive art can we preserve its poetry and musicality. We are the conductors, the directors of the film. If the designer fails to elevate the creative process beyond market strategy, the product ends up being just another object in the world… and the world is already full of objects.

RZ: If you had to choose a design object that best represents your philosophy, what would it be and why?

HT: I have a constant love for the Viennese chair: it is banal and beautiful, expressive and anonymous, universally accepted, and part of our common culture. It exists outside of time.

RZ: Sustainability and design: how do you integrate eco-friendly materials and processes into your projects?

HT: We have been working with sustainability for many years. It is a duty because we have only one planet, but it is also a great creative drive: waste materials, often ugly or raw, push us to experiment with new textures, colours, and sensitivities.

RZ: What is the key element that a good design can never overlook?

HT: Sometimes I love to make a sketch or a painting after creating a product. If I can’t make a clear and beautiful drawing of the object, then it means it lacks depth. I believe design must always be personal and intimate, a reflection of our lives and cultural stimuli. In our studio, we strongly believe in collaboration and mutual respect, because I have this somewhat naive vision: beautiful things, created with dignity and respect, have a beautiful soul.