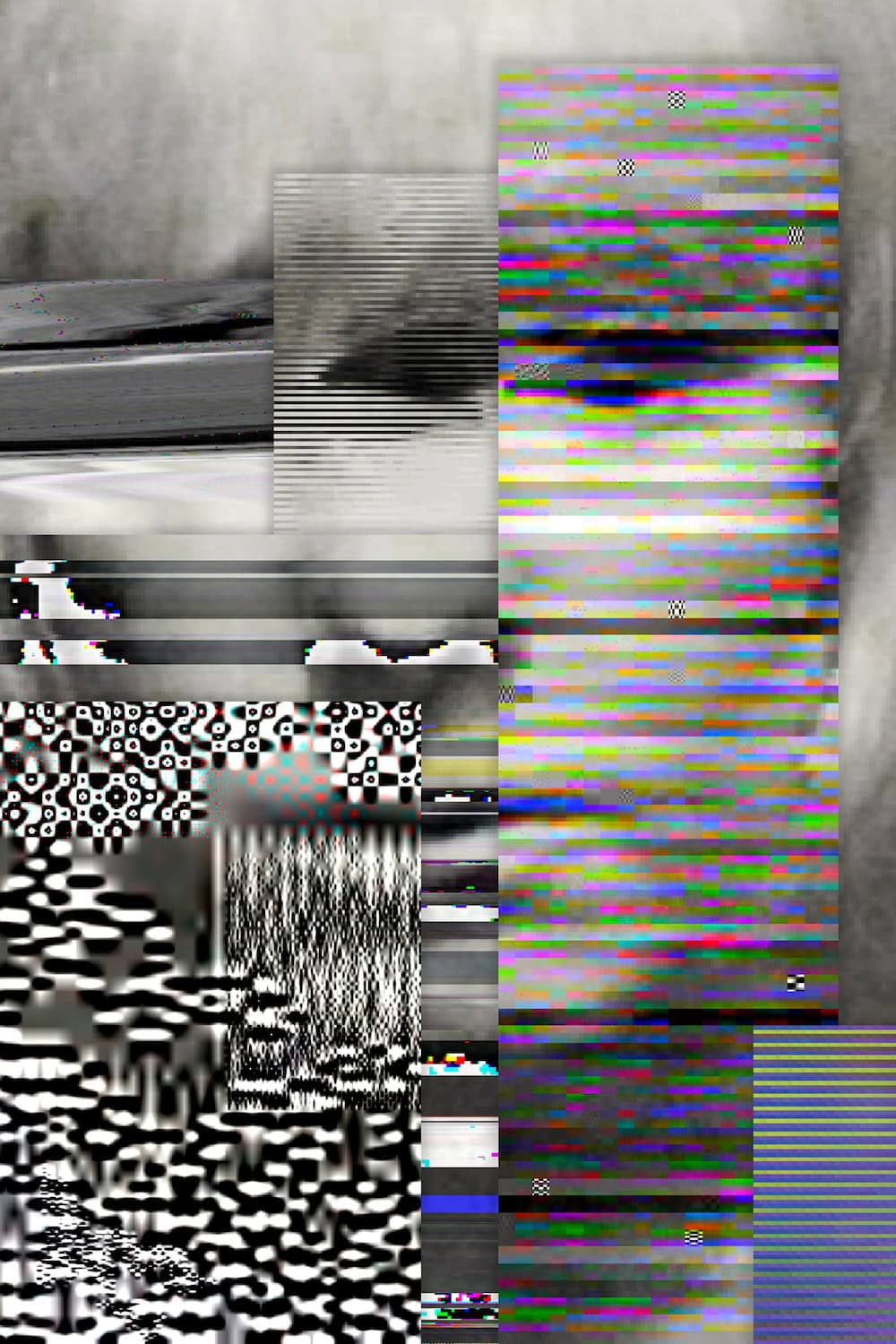

As one of the youngest and most unpredictable forms of art, “glitch art” specifically draws attention to the productive side of the flawed. Initially prevalent in the technical jargon of radio and television engineers in the 1950s, the term “glitch” (Early Modern High German: glitschen, meaning to glide or slither, or from the Yiddish gletshn, to slip or skid, to slide away) soon came to describe programming or graphic errors in the world of computer games. A glitch is thus the unexpected result of a malfunction that occurs not only in computer games but also in other digital software. In the art context, technical interference finds its immediate expression in the field of computer-generated images and digital work. However, its roots go back to the early days of the history of photography. As an artistic counter-movement to recognised forms of expression, the technical glitch takes its course from early photography via avant-garde film to video and sound art, as well as to digital image media and net art where glitches are intentionally provoked or deliberately programmed.

Ilaria Sponda: First of all, how has your work at the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich been going as a Chief Curator of Photography and Time-based Media?

Franziska Kunze: I do not only deal with photography but also with time-based media as you mention. The combination of the two media interests me the most. When we look at the artists working in the photography field, they often work with video art and vice versa: this combination is quite popular. I think they benefit, photographs and videos, really benefit from each other if they can be perceived together in the same space and not in separate rooms as often happens.

IS: In this particular exhibition Glitch. The Art of Interference, on view until March 17th, we see photography and video art dialoguing through the commonality of ‘glitch’. How did you arrive at conceiving this exhibition?

FK: This is a very special interest of mine, to work with image interference. I worked on it for quite a while, also I already wrote my dissertation on it. Actually, the first chapter of the exhibition is more or less, in a nutshell, a part of my dissertation. When I arrived at the Pinakothek der Moderne this was the first project I pitched. There have been many people before me working on it, of course, and there have been exhibitions but on a smaller scale than this. There are festivals that deal with image interference too. Texts have been written about it. But talking of large-scale projects, especially in an institution like this museum, I think this is quite a unique research. I got interested in the concept of ‘glitch’ because of its history and relation with art, specifically its misconception among people’s common knowledge: when thinking of glitch art, many people think of pixels and colorful images. Many also think of filters. But actually, glitch art is rooted in a media-reflective perspective.

IS: How would you describe the very concept of ‘glitch’?

FK: When conceiving the exhibition I sort of wanted to disappoint the museum’s digital native audience, who probably comes thinking to know all about glitch art. Analog photography is one starting point for telling the story–at least within technical image media. People who feel more comfortable with analog works can have a link to maybe understand digital media art and the other way around. I wanted to start in this unexpected way, showing works that have never been shown before in such a context and narrative.

IS: How come analog photography is a starting point of the exhibition and your perspective on glitch art?

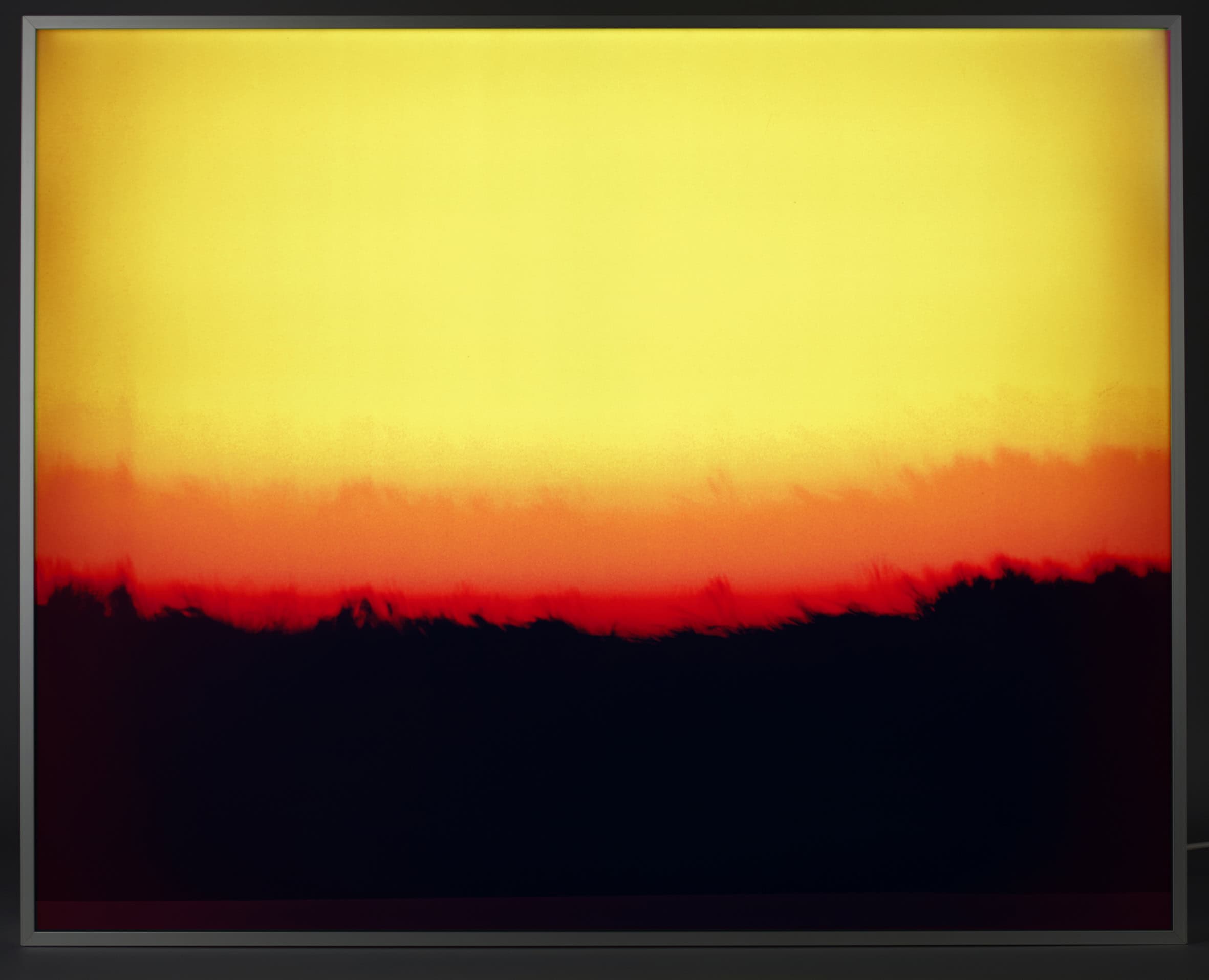

FK: Well, the first part of the exhibition is titled Born to Glitch, a statement to highlight photography as a medium that came into being mostly presenting photochemical soups thus appearing erroneous. Developers and photographers tried hard to achieve the representational images that we are used to right now. In the 20th century, people tried to break these rules and do something outside of the box and to turn the perspective completely around. Those are very brave perspectives because this was nothing that the market was interested in, not at all.

IS: Could you highlight any of the female artists that are shown in the exhibition?

FK: Firstly, Johanna Reich. She’s from Cologne and in the exhibited video work she kicks a video camera, an analog video camera, through the streets of the city. It is a sort of video performance. As she’s kicking the camera, the resulting images composing the video are turned upside down, distorted, and sometimes the image signal is severely interrupted. There is also in the first chapter a photography work by Evelyn Richter, known for her documentary approach. There is just this one single image presented at the Pinakothek der Moderne which shows something completely different from her usual work. It’s a photograph taken in the 1950s, so right after World War II, and shows the Dresden Frauenkirche (“Church of Our Lady Dresden”). The city represented is destroyed and the church is destroyed too. This destruction was intensified by the chemical treatment of the photographic surface. Rosa Menkman, Steina Vazulka, Esther Hunziker, Mame-Diarra Niang, and Maya Dunietz are among other perspective on glitches by women.

IS: Where does glitch art trace back according to you?

FK: Well, since glitch art is a movement and not an art form it is really hard to give a precise start to it. The movement came up in the 1990s. It came into being through the spirit of computational art and, of course, digital art. Being highly linked to electronic media, at some point, the glitch artist movement was already traced back to early video art. But my proposition within the exhibition is to go even further back. When you think of technical media, which photography is part of, it is natural to think of their developments to achieve a perfect transposition of reality into an image. In the 20th century, specifically in the 20s, early experimental works tried to challenge pure representation–think of the Surrealist movement. During World War II Germany witnessed photography being used by the Nazi regime for propaganda so for many years the medium was not experimentally used at all. I have the feeling that all of these artists who wanted to work again with photography had to destroy the medium in a way in order to rebuild it. I see it as a way to regain artistic power over a medium that has been used for propaganda for such a long time.

IS: What do glitches tell of the globalised information network of today?

FK: I think one could start off thinking about this question by looking back at our behaviour throughout the last years, during the pandemic. Within the moments of everyday routine, being on video calls and seeing faces dissolving into pixels due to unstable connections annoyed us or made us smile because it was turning the routine upside down and breaking the normal. Image interference can be used as a tool to activate our attention and as a tool for intervention and commentary on social and political issues that sometimes I would say cannot be made visible with the mainstream media. If you consider Nam June Paik’s work exhibited at the Pinakothek der Moderne, you see a TV with a compilation of several speeches of Richard Nixon.. When pushing a button, the video gets distorted. This represents the warped content of some political speeches up until now. And this is what I think is the most interesting thing about the glitch art movement, that as long as you live in a society familiar with electronic or technical media, I think you can read the images that these artists produce quite easily, without the boundaries of languages. And this makes it a global phenomenon according to my vision.