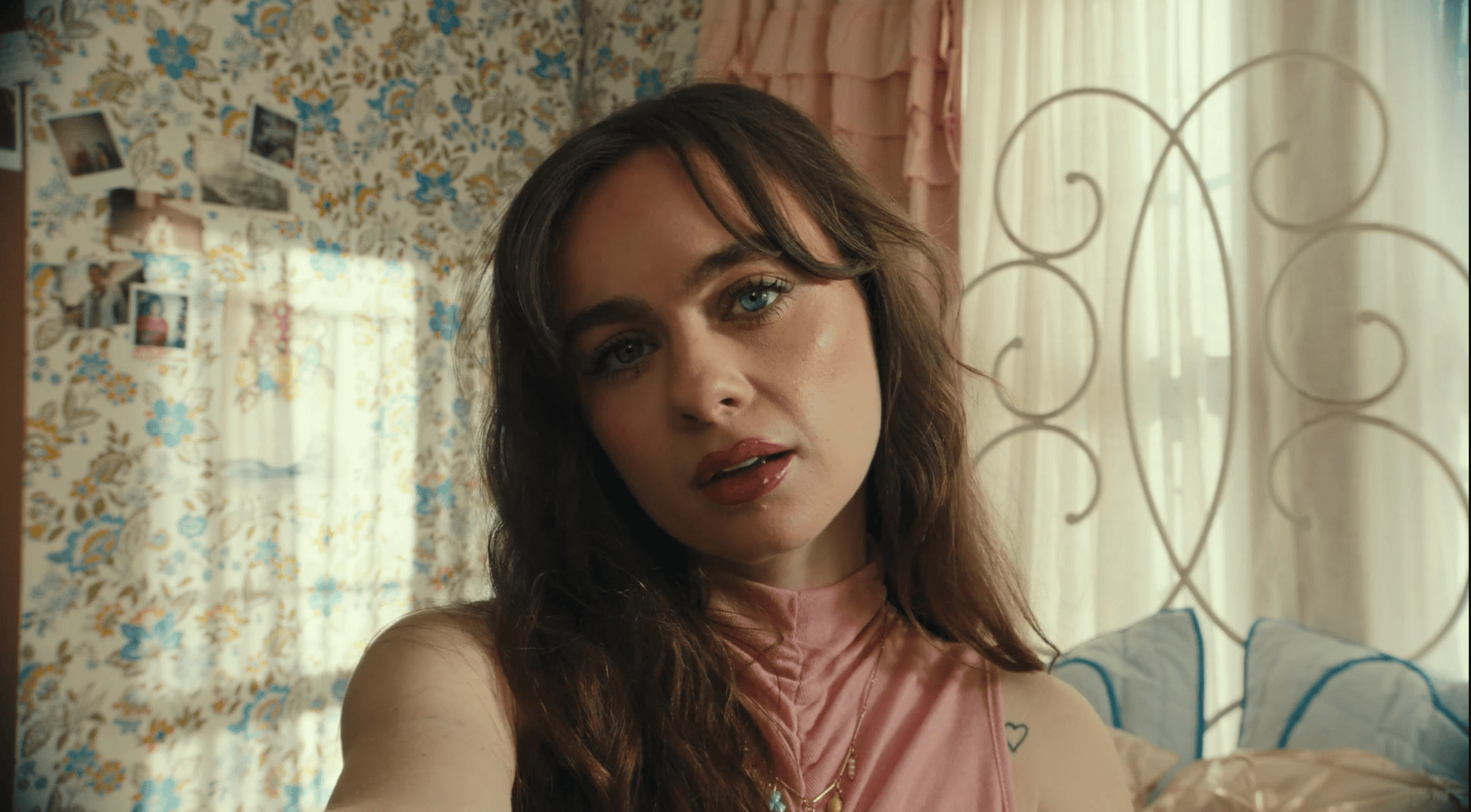

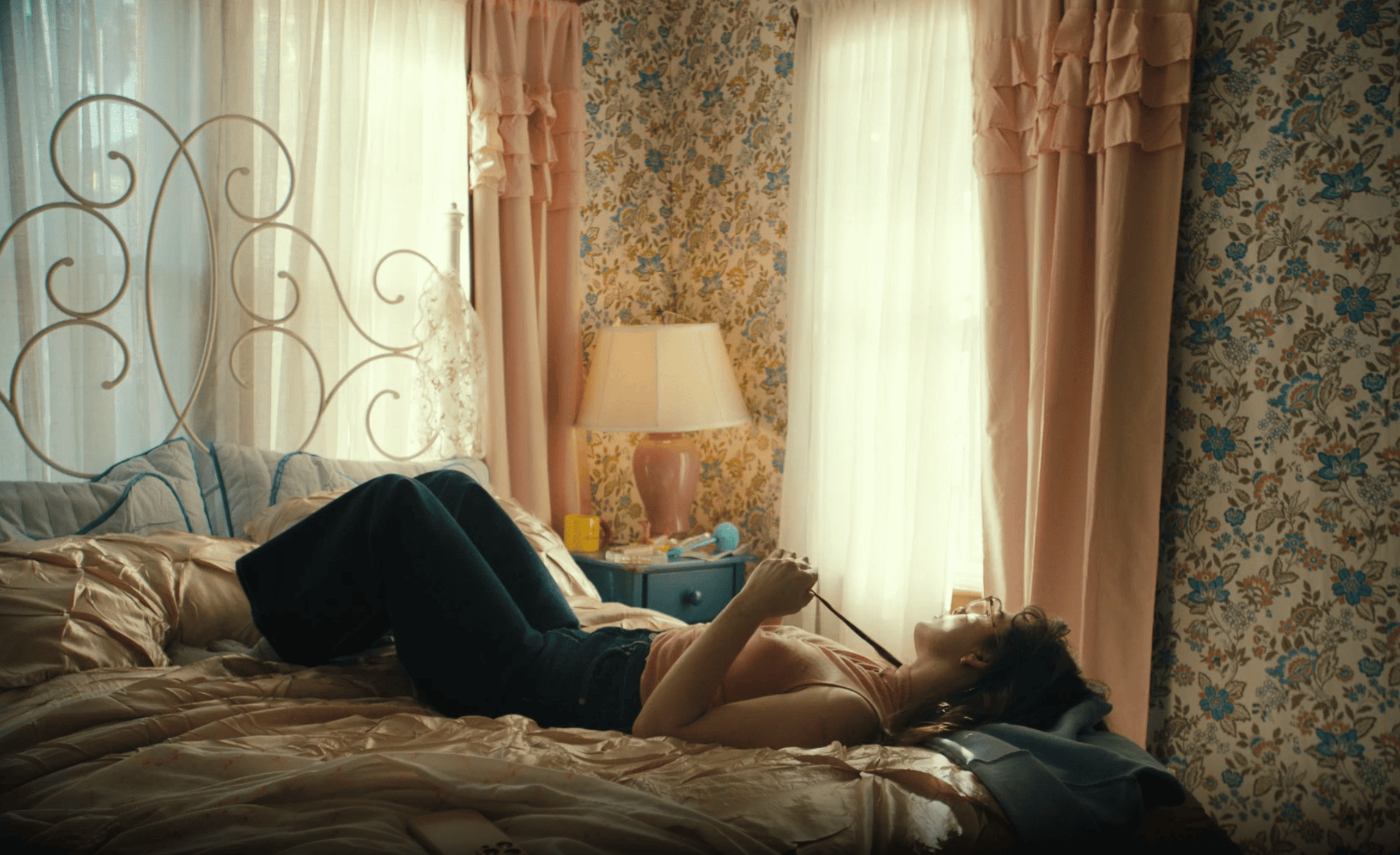

Immersed in the melancholy of imaginary suburbias, filled with floral wallpaper and meaningful silences, Bianca Poletti’s short films portray intimacy in its most disarming form. With a strong visual sensitivity, the director and screenwriter builds emotional microcosms made of lived-in rooms, solitary adolescences, and imperfect relationships. In this conversation, Bianca Poletti shares how her visual worlds come to life, the role of childhood and solitude in her poetics, and the challenges of representing vulnerability in an age dominated by filters and algorithms. At the center of the dialogue is FaceTweak, her two-minute short that explores the digital distortions of body image with irony and unease.

Ritamorena Zotti: Your work is often immersed in a dreamlike and melancholic aesthetic — how do you build the visual atmosphere of your stories?

Bianca Poletti: I usually like to pick a location or world, and then I build the stories around that. Growing up, my mom was always house hunting, going on house tours of fixer-uppers and properties she could buy, redo, and resell. My sister and I would help her break down the space of the homes and imagine what they could be — with a facelift, with some color, texture, and life added. I think my love for spaces started there. I love walking into any sort of space and seeing what kinds of stories the walls can tell.

I’ve also always been in love with “Tim Burton meets Sofia Coppola” sort of worlds — colorful, wallpapered homes and seemingly perfect American suburbia, but with an undercurrent of loneliness. I’m drawn to the feeling of perfection masking sadness, and I love building stories around those themes and exploring them. When prepping for a shoot, I usually start with the location and then pull inspiration mostly from photography. For Face Tweak, for example, I pulled a lot from photography books about girlhood — Justine Kurland’s work, Bill Owens’ Suburbia series — and crafted from there.

RZ: Is there a moment from your adolescence that you find yourself constantly revisiting or reworking through your projects?

BP: Great question. Definitely a general feeling of coming of age is something that’s in almost all of my work — and a bit of loneliness, too. Growing up, I always felt like a bit of an outcast, clumsily falling into who I wanted to be. It took a bit longer than maybe it does for the average person, and honestly, I’m still learning and changing every day.

The loneliness part: I spent a lot of time as a kid alone at home. My mom was a single mom who worked a lot to take care of my sister and me. My sister was often out with friends, so I spent a lot of time by myself — drawing, creating one-person plays, watching movies and TV shows, reading books — always in my own imagination and play world. I’m happy I went through all of that now because it helped me keep a spirit of imagination and play, but in the moment, it was definitely lonely. Those themes have stayed pretty consistent in my work.

RZ: Many of your works celebrate tenderness, but never in a naïve way. How do you portray intimacy without falling into clichés or stereotypes?

BP: Thank you — that’s really kind of you to say. I try to approach intimacy through a real lens (hopefully it comes across that way), trying to recreate how messy, embarrassing at times, exhilarating, weird, and clumsy intimacy can be with another human. No one is perfect, and what I love most about humans is how imperfect we all are — it’s interesting stuff. So, I try to dig into real-life imperfections and memories, and tell the story through that lens rather than through some polished, picture-perfect idea.

RZ: The relationships you depict are subtle, authentic, never forced. How important is it for you that representation isn’t “educational” but emotional, visceral?

BP: Very important. I never want to tell a story in a one-sided way. I’m not interested in telling people how to feel about something. I just want to portray how it might feel to be in the protagonist’s position. I try to heighten every emotion and feeling visually — with the right music, edit, and sound design (thank you Abbey Hendrix, Dusten Zimmerman, and Natalie Huizenga for all your help with that!) — to help people step into the hero’s shoes and experience something either new or familiar. I want to open the door to a concept or feeling and let the audience take it wherever they want emotionally.

RZ: In a world increasingly saturated with fast-paced imagery, how do you cultivate intimacy and slowness in your work?

BP: Oof. Great question! I definitely struggle with this sometimes. Working in advertising, it’s often about telling a full story in six or fifteen seconds, without a second longer to stay on a face or let a moment breathe. So when it comes to my film projects, I really try to take my time where it’s necessary.

It takes time to watch someone go through something — to feel it with them. It takes time to establish relationships and build worlds. If it’s possible, I’ll let silence be okay. I’ll let an opening shot take its time before landing on the hero of the story. That said, I also love films that are entertaining. There are moments to slow down and allow silence, but there are also scenes where you need to pick up the pace.

For example, I love Severance, but Season 2 took me a long time to finish because the pacing was so slow — until the last two episodes, when everything finally started happening. I think it’s important to strike a balance.

RZ: FaceTweak is ironic, but it strikes a nerve: the way we craft our digital selves today. Where did the idea come from, and how did you decide on the tone?

BP: I was spending a lot of time on TikTok, researching for a commercial job, and going through hours and hours of videos — from girls to women, ages 16 to 50. Every single beauty video, or video in general, seemed to be about fixing flaws. A lot of the younger girls only showed themselves with filters on, or posted before-and-afters of Facetuned versions of themselves, or AI versions they were trying to replicate with surgery.

I find beauty standards for women and young girls incredibly interesting — how they change over time, and how some things never really change: the pressure to be “perfect.”

I’ve dealt with a lot of that myself. I used to use filters heavily on photos, I struggled with anorexia as a teen, and I carried a lot of self-shame. I wanted to tell a story within this world — but not in a preachy, sad PSA way.

The reality is: it’s okay to fix things about your appearance if it makes you feel more confident. It’s great to be healthy and feel good about yourself. The problem comes when the extremes take over — when nothing is ever enough. No one will ever be pretty enough, thin enough, perfect enough — because that concept doesn’t really exist.

So I wanted to explore that, in a more Black Mirror sort of tone, incorporating AI and leaving things a bit open-ended. FaceTweak is more about the feeling — when do you know you’ve gone too far? Is there a limit?

RZ: The short is only two minutes long, yet it’s packed with pop culture and social media references. What was the biggest challenge in condensing so much into such a short format?

BP: There’s definitely a bigger story here to explore. But I had a location locked to shoot the trailer for another short of mine, Video Barn, and the location was really interesting and textured. We only needed a half day to shoot the trailer, so I quickly wrote FaceTweak, knowing it could be shot in under three hours with minimal crew and one talent.

It was condensed from the start, but I liked the challenge of telling a story in a short amount of time, without a dialogue-heavy script. I wrote it knowing this was just one moment in her life that we’re witnessing.

The social media videos were filmed by friends of mine during the edit — on their own phones, in their own wardrobe — so that part came together quickly. Overall, the biggest challenge was crafting the tone, and figuring out how simple we could get with the setups and shots to still tell the story: one talent, one room, two total camera setups, three hours. It was a fun challenge.