Back in the Seventies, Italy went through an impactful oil crisis. This led to raw materials scarcity, which designers faced experimenting with poor, new materials available in the country. Those were also the years when designer Enzo Mari stood out. In 1974, he published the book Autoprogettazione with instructions on how to build easy-to-assemble, DIY furniture using as raw material only rough boards and nails. “Autoprogettazione” is a concept that brings awareness of the process of “making” and design, a method to instruct readers to build practical and useful furniture pieces through very simple techniques, giving more relevance to the act of making rather than the object being made. Mari was an artist first, thus craft was intrinsic to his approach and his design has been appointed as “social” in the sense of it being for the people and not just a privilege for the wealthy. We’re sharing today two conversations held with Giovanna Silva, photographer and author of Desertions, and Simone Lorusso, who’s developed a series inspired by Mari’s philosophy and design themselves.

Ilaria Sponda: Hi Giovanna, it’s a pleasure conversing with you about your book and film Desertions. What is the first memory that comes to mind when you think of Enzo Mari and the journey through the Northern American deserts?

Giovanna Silva: Sprite, this carbonated, sugary water-like drink that Mari had never tried but of which he overdosed hyperglycemic during the trip. And his panama hat. And the cigar. And the perfect dollar shape. Every time I intercept a dollar, increasingly rare in the now credit card world, a thought returns to those moments.

IS: Deserts as “the origin of the world,” as you write in Desertions. What fascinated Mari about the deserts?

GS: More than deserts, it was the American deserts that fascinated him, or rather, maybe America in general, which is made up of huge empty and abandoned spaces, in a word deserts. America was something far away from Mari, his culture, and his ideologies, more than far away I would dare say that America did not arouse any form of fascination in him, in fact, the only two things that the quintessential capitalist culture, the American culture, had created were the dollar, in its perfect form and always the same, and highways. Like all things we detest, there is a form of perverse attraction that causes us to experience them, hence our journey to the American deserts, from Los Angeles to Las Vegas via Palm Springs.

IS: The social aspects of design, reflection on form, and the collective value of the work: how have these pillars of Mari’s work influenced contemporary designers?

GS: I believe that Mari’s strength was not in his products but in the intransigence of his ideas. Mari founded ideological pillars in contemporary design and never betrayed his principles. I think his principle was a moral rather than a formal teaching. Be what you are, whether you are a nail or whatever.

IS: Jumping back to Desertions: it’s a written and visual document of great value and memory that is now historical. What was the process of designing and developing the book like?

GS: I actually published two books, with the same publisher (a+m Bookstore) but years apart. The first one was published in 2007, one year after the trip. It was my first book. It was a mostly photographic book where photos of the American landscape alternated with pictures of Mari on the road. Now, after compulsively publishing 25 of them, I have my own idea of bookmaking; I wanted to republish it in a new layout, asked Mari’s permission, and also reposted for the occasion some mini DVDs I had shot without any real design consciousness during the trip. Listening to the footage again, I realized that there was a new book in his words; it was not only my landscapes but also Mari’s testimony. The new edition therefore combines his words the frames of the video and the photographs of the landscape traversed.

IS: What kind of memory of Mari did you try to communicate with your book and film Desertions?

GS: I tried to communicate my affection for Mari. We dated for a long time even after the trip, for him, I remained forever crystallized in my 27 years and the nickname of “figliolina”, Italian diminutive for “figlia”, thus “daughter”. For me, Desertions is Mari, a person endowed with an out-of-the-ordinary intelligence, a gruff being who nevertheless hid an infinite tenderness. The book plays precisely on these two aspects, Mari’s design strength and his ideas, and the in every sense human side of the great designer.

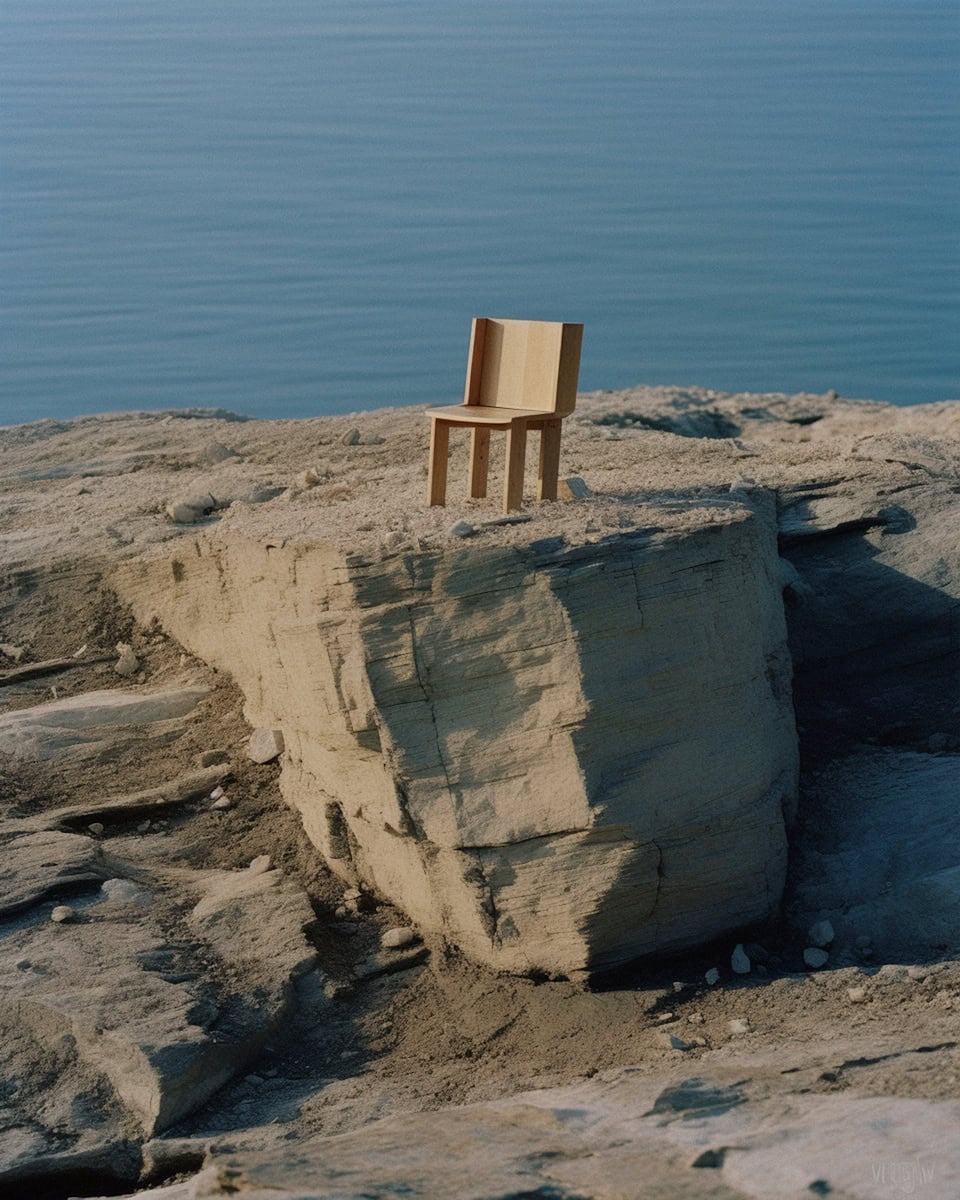

IS: Hi Simone, I’m glad to have this opportunity to delve deep into your last series. What’s behind Sitting in Solitude?

Simone Lorusso: Ilaria, I want to extend my heartfelt gratitude for this interview. It’s providing me with the opportunity to discuss a beautiful project, an unfettered designer, and pressing, enduring themes. Again, I’d like to commend Giovanna Silva and Studio Mare for their fantastic work, specifically Margherita, as we were schoolmates. The series Sitting in Solitude draws its title directly from the title given to the project by Giovanna Silva: Desertion. The word “desertion” evokes the idea of a desert and carries the meaning of abandonment. More specifically, it signifies a contemplation with oneself, in solitude, regarding the essence of design and the world around us. This is precisely why we feel alone — engaged in a contemplative exploration of design’s meaning and its relationship to our surroundings. For me, the chair has always been a highly intriguing object, not only for its design aspects but also for its political and social significance. One only needs to consider the most significant political discussions, protests, and many of our daily actions and gestures that are carried out while seated, precisely for this aspect of contemplation and reflection. Chairs, in their seemingly simple design, hold a deeper layer of symbolism, embodying a space where ideas are exchanged, decisions are made, and perspectives are contemplated.

IS: Where does your fascination for Mari come from?

SL: My fascination with Mari traces back to around 2012 if I recall correctly. I was approximately 20 years old (a photography student), when I came across Artek’s publication of chair N° 1(visual reference for this project), taken from the Autoprogettazione catalog. Intrigued by this, I delved into Mari’s initial research. I was immediately captivated by the “DIY” concept and, more importantly, the notion of design breaking away from overly pervasive industrial control. In Mari’s proposition, there is a critical attitude towards large-scale production, recognizing the potential deprivation of individuals’ ability to create. Essentially, Mari’s ideas laid the groundwork for the current European regulation on ecodesign, emphasizing the importance of a DIY ethos and encouraging a more thoughtful and sustainable approach to design that empowers people to engage with their creative capabilities.

IS: Mari’s design is known for its impact on “projectuality”. How could this method apply to photography?

SL: That’s a very interesting question, albeit challenging to answer. Design must inherently possess a functional aspect in form, use, and functionality. Photography, on the other hand, differs in this aspect. However, in a general sense, Mari was an atypical designer, far from the concept of a classic design, as we often tend to imagine it today. Politics heavily influenced his production, and his identity as a thinker and craftsman before being a designer. In this sense, photography follows a similar path—designing images that reflect, to varying degrees, socio-political aspects. Just as Mari aimed for inclusivity and a democratic approach to design, photography can strive to capture and represent various perspectives and societal narratives, making it a tool for expression and communication that belongs to everyone.

IS: What has your experience of the desert been while developing this project?

SL: I have always been both fascinated and, at the same time, intimidated by the desert. In recent years, my interest in the gradual desertification of the land has deepened, considering it one of the most significant threats to our planet, both on a social and economic level. According to the most widely accepted definition by the UNCCD (United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification), which came into effect in December 1996, desertification is the progressive loss of soil fertility, rendering it incapable of supporting agricultural production or various species of spontaneous vegetation. I won’t delve into this lengthy discourse. Still, I’ll pause for a moment to reflect on one of the primary causes: unsustainable use of natural resources, such as industrialized agricultural practices. This brings us back to the discussion mentioned at the beginning of this interview regarding Mari and his critique of the industrialized design process. Just as Mari advocated for a more sustainable and inclusive approach to design, acknowledging the repercussions of excessive industrialization, the issue of unsustainable resource usage in desertification reinforces the importance of mindful practices and a holistic perspective toward our environment.

IS: Photographic practices can be charged with solitude. How do you relate to it?

SL: I’ve always felt like a solitary soul; I’ve never been fond of the idea of being part of a group and have always seen solitude as a moment of personal enrichment and reflection with myself—perfect for “creating art.” However, as one grows, fate introduced me to someone, Filippo. It was wonderful to find a person who was not only your boyfriend but also your partner in work, someone to study with, to conduct research. To make art. We lived together in Rotterdam, and for C41, we collaborated on Rotterdam Make it Happen (I handled the photos and he conducted the interviews). We also delved into discussions about ecology, society, and politics with the project Re-Generation. Now, this person is no longer in my life, but that’s another story. Life unfolds, and experiences shape us, altering the way we relate to solitude and creativity.