Throughout time, the narrative around bodies has changed as a consequence of social and cultural dynamics that have turned them into mere objects. Lifeless entities bound to serve stereotypes and adhere to labels. The stories that our bodies tell are not solely based on what they carry, but also on society’s expectations about them. But what happens when these assumptions interact with more than just one category? Black, brown, fat, disabled, and queer are just a few of the many realities in which our bodies live. And what happens when these categories are not seen as worthy of living in?

Social media, fashion, and cosmetics—to name a few—have built their foundations on beauty standards that cater to just one specific story, whose main claim is “perfection”. A goal that can be achieved exclusively by displaying the features and characteristics that reflect social norms: straight, white, abled, slim, and prude.

What about the rest of us? What about the bodies that deviate from such models? We like to believe that each century has brought us closer to progress, to the ideal society where everyone is equal and equally vocal. However, some body types and stories are yet to be seen and heard. Where are the “others”? This has led specific groups of people to realise that what they were seeing on TV, in magazines, and in campaigns wasn’t exactly what they were encountering in the real world.

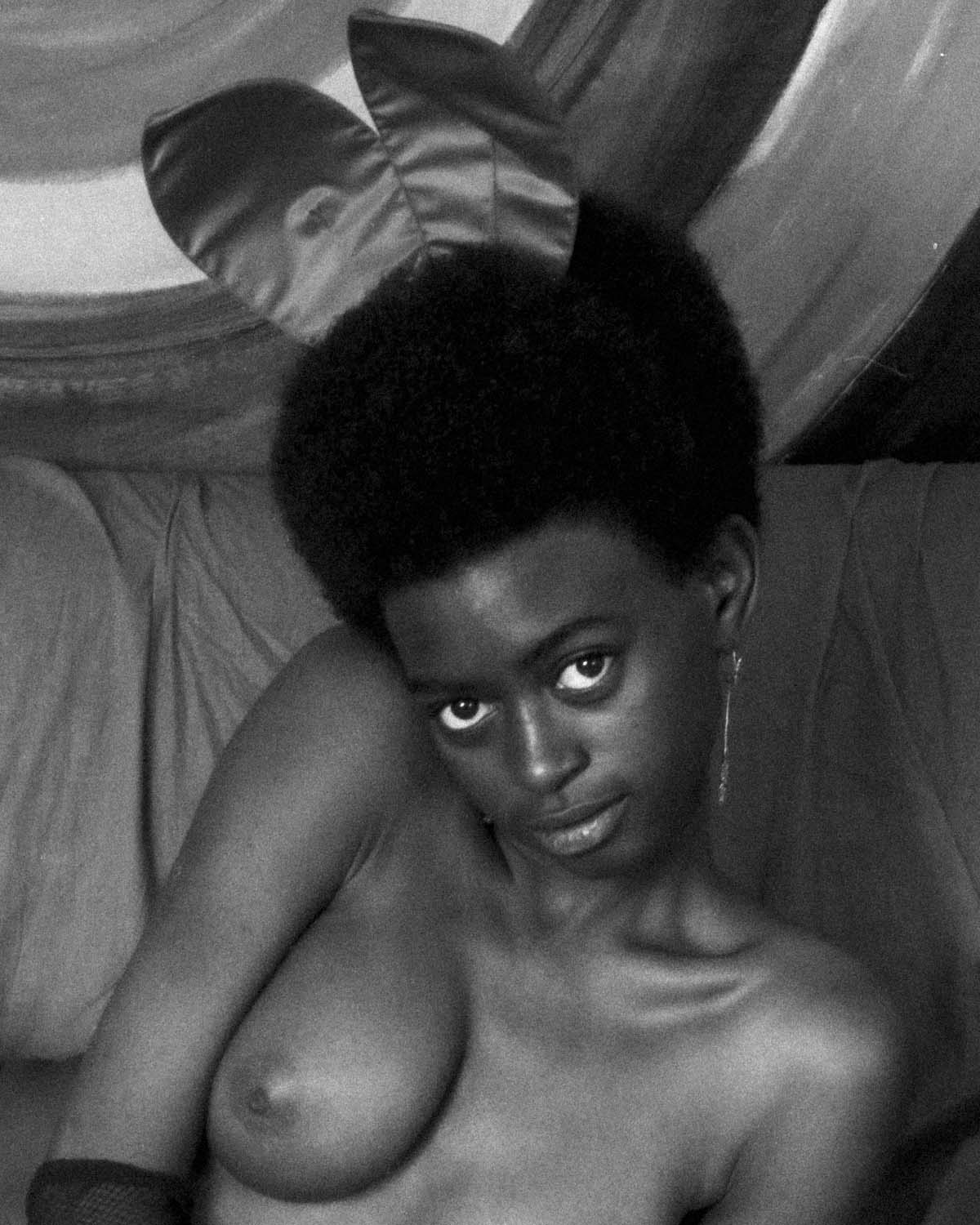

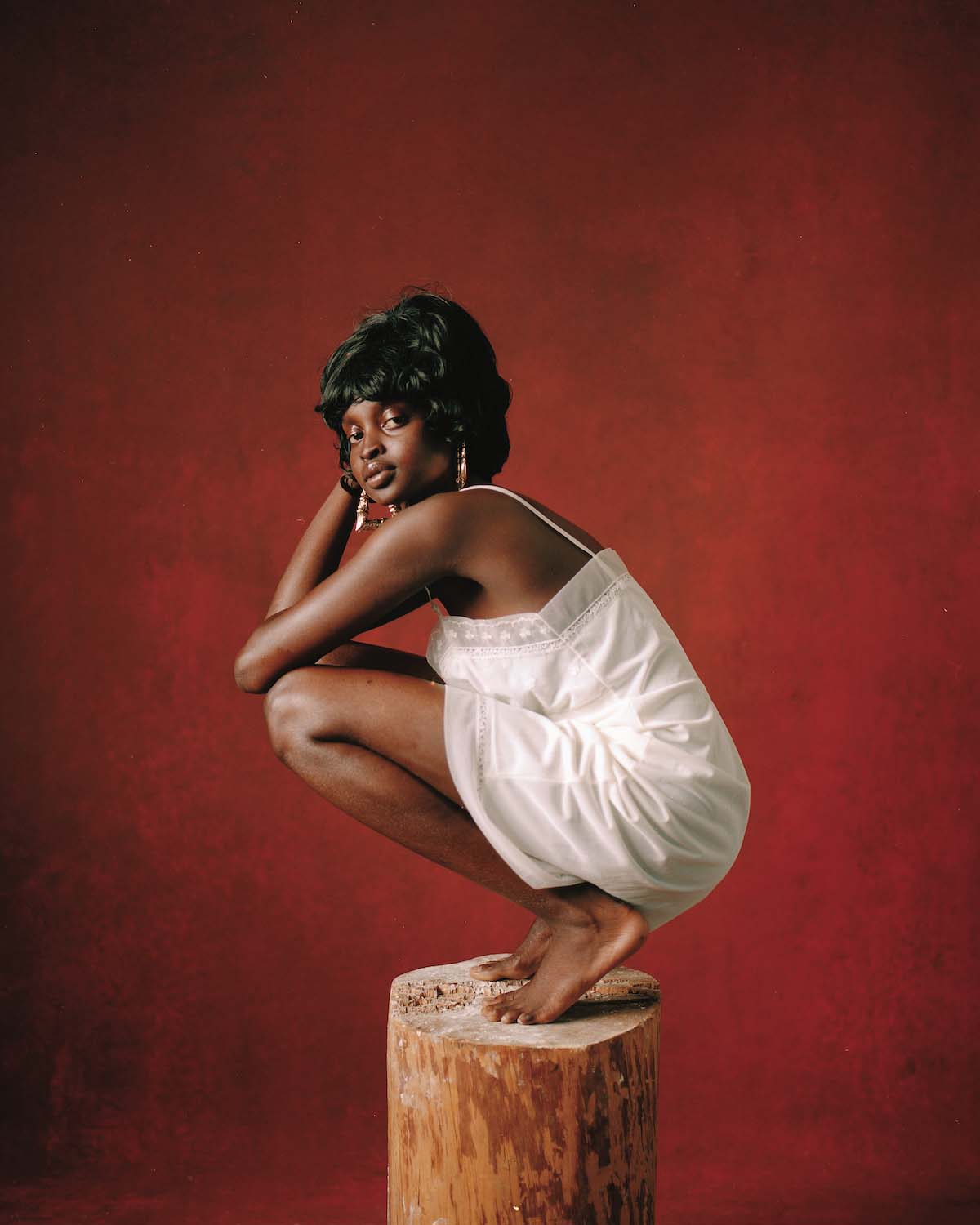

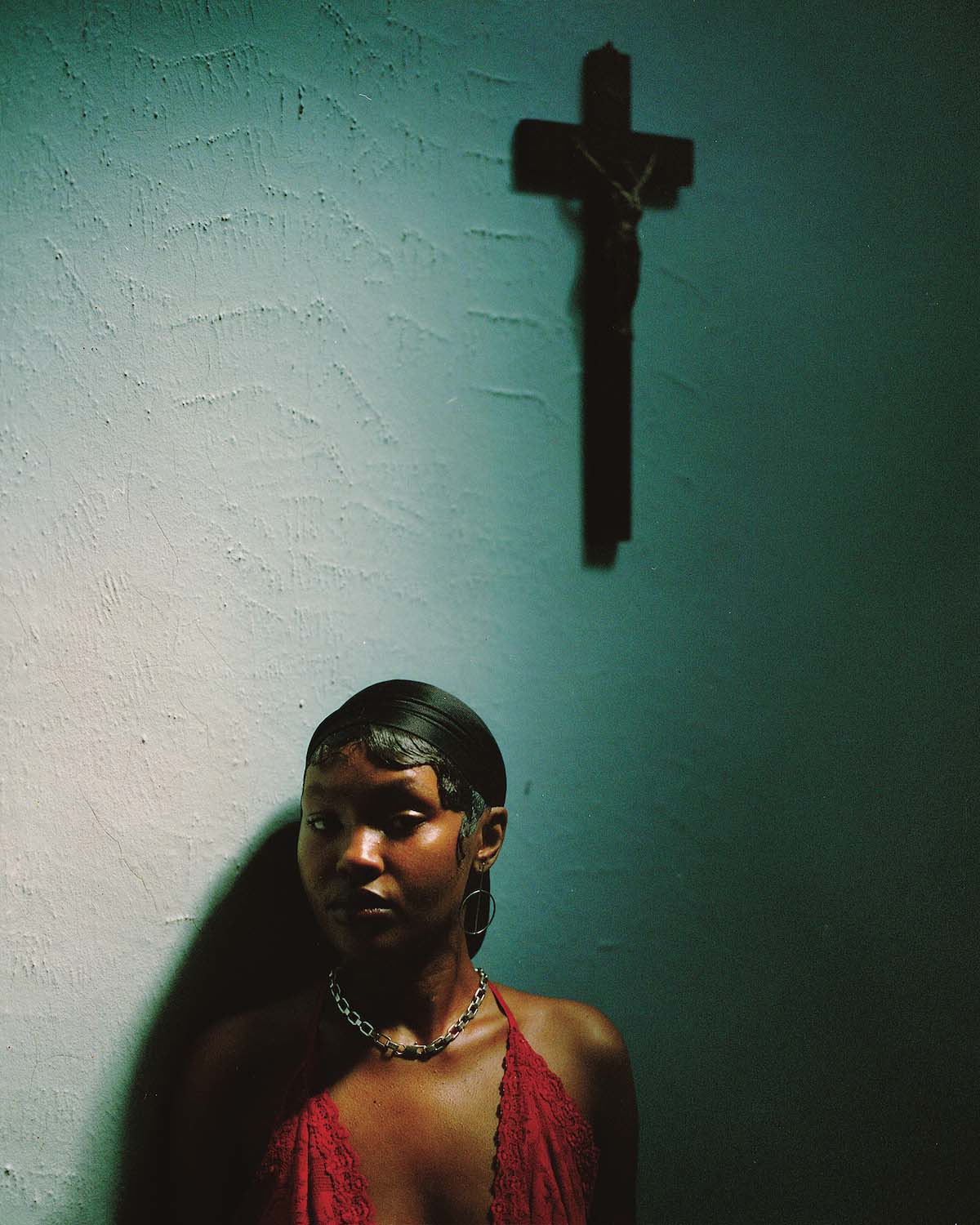

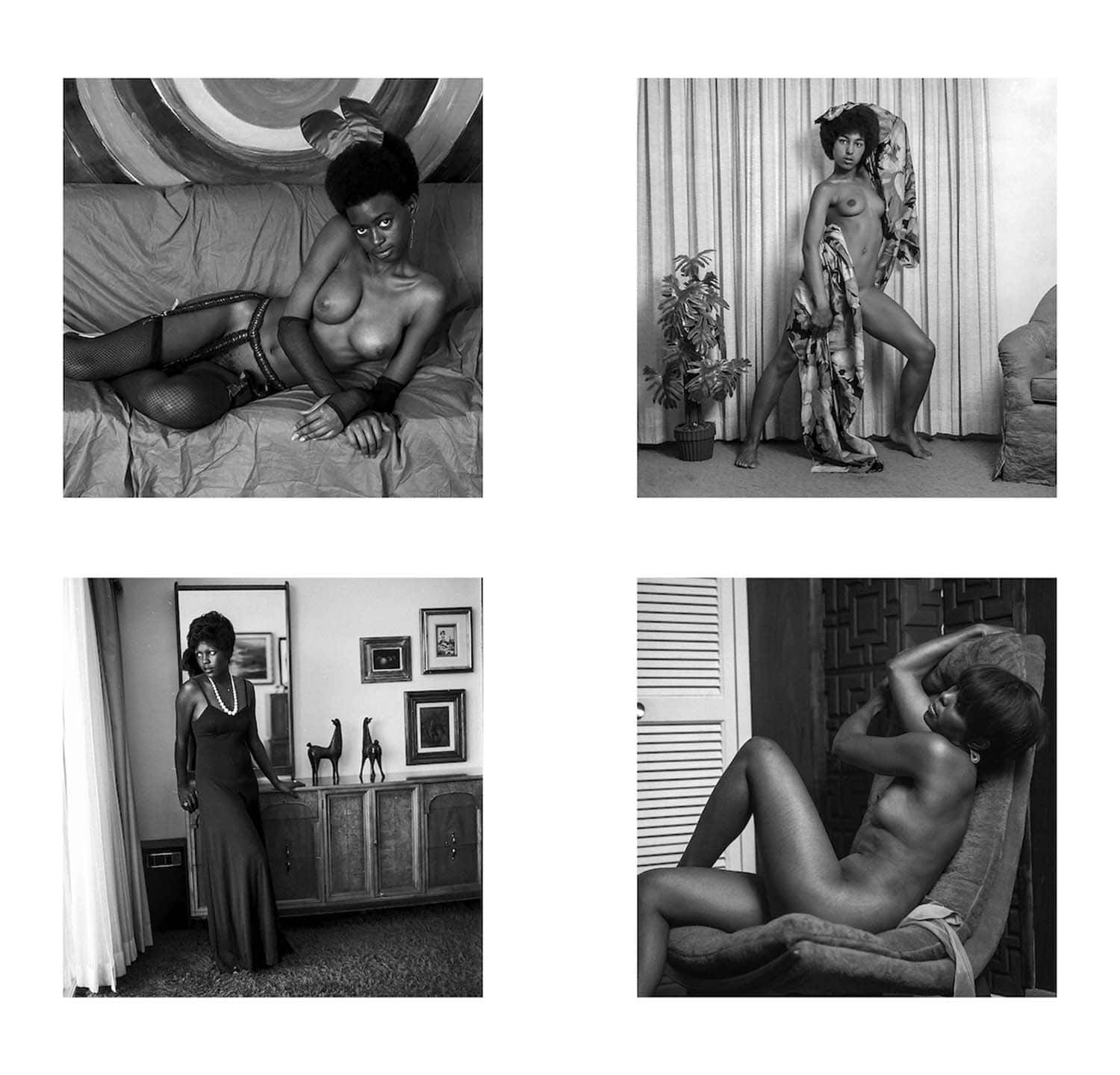

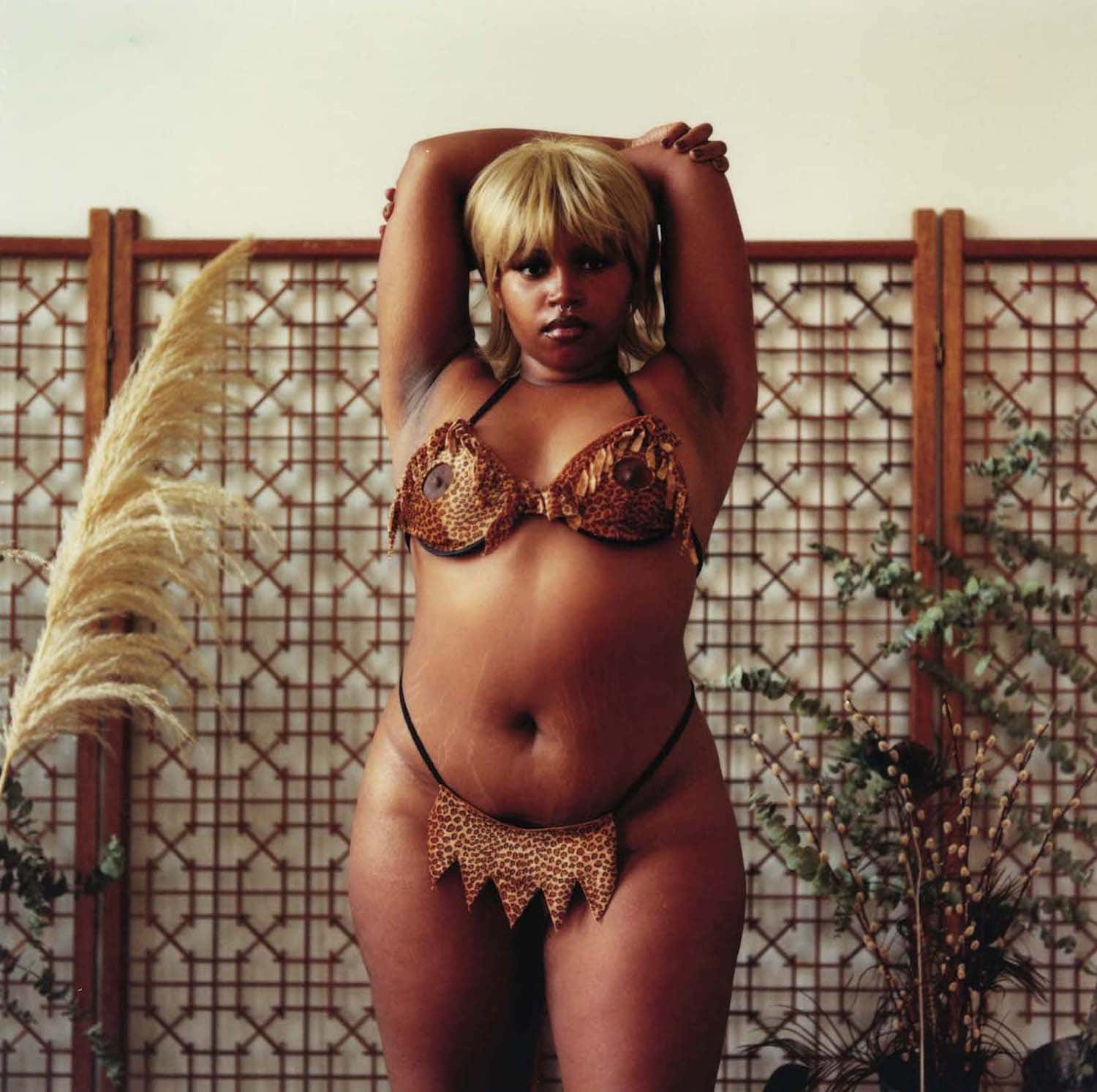

Audre Lorde, the famous Black, female, queer poet has shaped words and covered pages trying to unravel the stories behind the bodies of Black women. Bodies that for centuries have been cancelled and silenced, not just in politics, medicine, and similar, but also in art. That is why it is essential to give space and create platforms where artists can bring forward narratives that question the very essence of perfection. Photographer Kennedi Carter, similarly to Audre Lorde, uses her camera to capture the past, the present, and the future of what it is to inhabit a Black body. Her stories are centred on the socio-political dynamics of Black life as well as the aesthetics of skin, texture, trauma, peace, love, and community. Her goal is to reinvent notions of creativity in the realm of Blackness. Her works have been featured in famous magazines and she has had the pleasure of shooting Black and Brown game-changers. We had the opportunity to chat with her about the importance of telling stories that break away from socially embedded biases and which spread awareness of how complex and diverse the Black female body is by discussing intimacy, nudity, and sexuality.

Naomi Kelechi Di Meo: In her poem Woman, Audre Lorde describes the Black female body as an “endless harvest”. How does such an idea impact the way you interact with your body and the bodies of your models?

Kennedi Carter: To properly answer, I need to take a step back and point out why I decided to photograph Black women—especially naked—in the first place. I think part of it has to do with recognising my queerness during my teenage years, as someone who grew up in the American south. It is not just a matter of attraction or care, but it is also a way of expressing my sexuality in a way I couldn’t when I was younger. Now that I am older and I know who I am and what I want, I have more room to play around and explore womanhood, including as an act of worship.

NKDM: Is there any particular aspect of the female body that you want to highlight in your pictures?

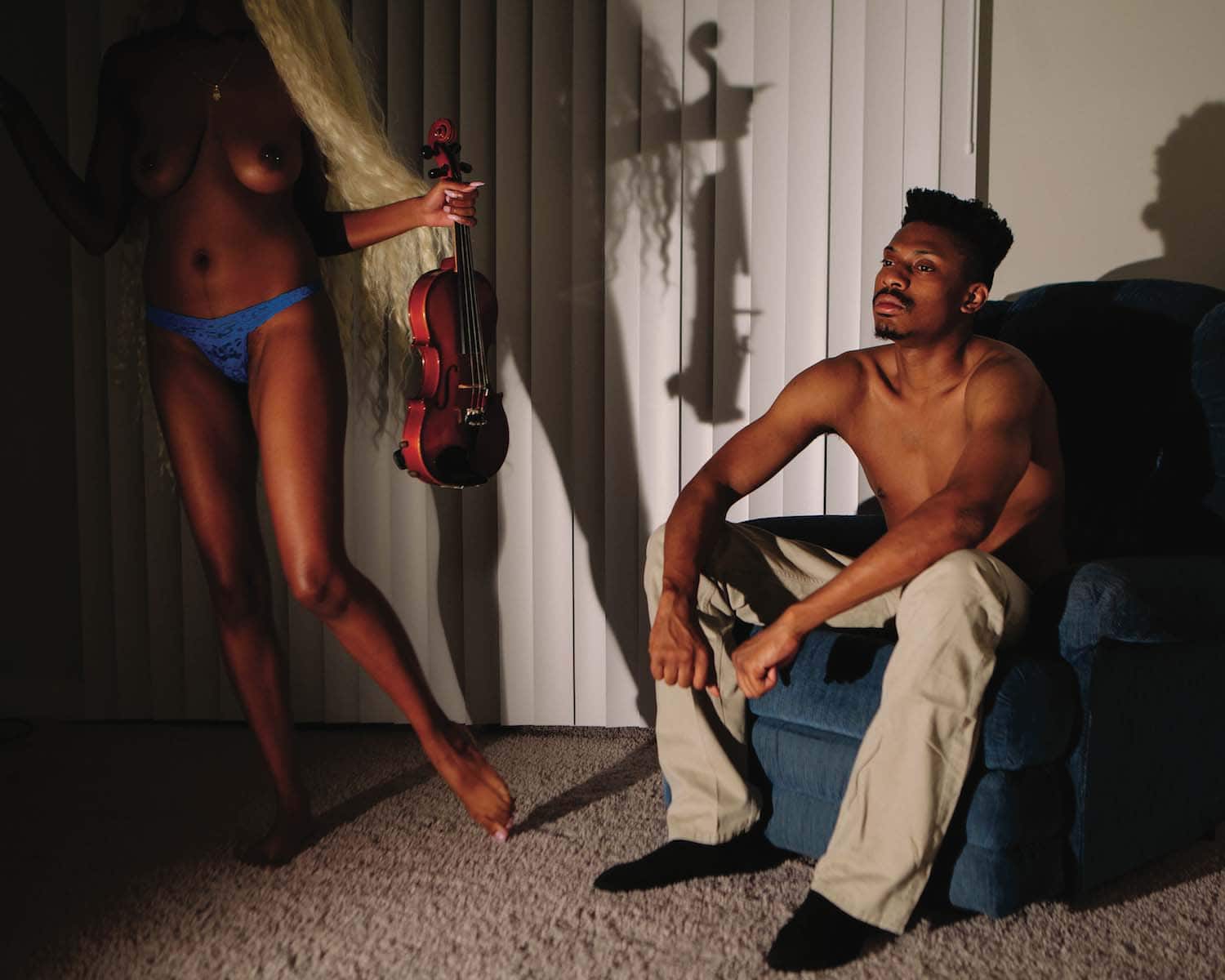

KC: Not necessarily. I get inspiration from the energy that someone has. Sexiness and attraction can be explored in many ways, not just through something physical like the body. I have this trans friend who I find very sexy and that feeling has to do with her confidence. I am mesmerised by the way she navigates the world and leads forwardly with that sexuality. I am moved by how a person gravitates around their own sexiness and intimacy. That is what I want to capture.

NKDM: Nudity has become less and less of a taboo. However, female bodies are still very much controlled, especially when undressed: what do you aim for when shooting naked bodies?

KC: It depends. But since my sitters are mostly Black women, I tend to be more careful about who can purchase and own my works. Black women have a peculiar relationship with nudity, sexuality, and intimacy as a whole, and the stories they tell with their naked bodies are delicate. I want to make sure that they don’t get exploited.

NKDM: How do you describe the relationship between the camera and your subjects?

KC: I usually shoot people that go into the experience 100% sure of what the deal is. But I can still sense the feeling of discomfort around them while shooting. I think that with time, I have developed a method to make sure they feel at ease: I interact with the models as if they were clothed, and I make sure they are okay by checking on them regularly throughout the shooting. Once they understand that the experience is not so different from a clothed shoot, everything becomes more natural. Sometimes my sitters think they need to perform in front of the camera… I always remind them that it is not a performance and that the goal is to capture their being. But it is a process that takes time.

NKDM: How do the stories of your sitters influence your creative process while shooting?

KC: I photograph people from all social backgrounds. However, there are certain aspects that I look for while thinking about projects or collections. For example, I really enjoy taking pictures of mothers, trans women, strippers, and rappers. I love getting to the bottom of who these people are. I want them to say who they are through my pictures, without us having to make any assumptions. That’s the core of my creative process: people.

NKDM: Art has turned into a tool for awareness about political issues. Would you describe your art and vision as politicised?

KC: I think everything is rooted in politics and history, whether we like it or not. History informs everything we do, and for us to learn from our history we need to read between the lines. I do a lot of research and dive deep into what it means to be a Black woman, jumping from Sara Baartman to archives of Black pin-ups, to pictures of women holding their driving licences, and so on. We have to look at the bigger picture, at what was here before us, to properly understand the world around us today.

NKDM: In your opinion, what is lacking in photography or any other medium when displaying bodies, nudity, or intimacy?

KC: Honestly, I am not entirely sure, because what I have encountered in art has always been done with a lot of beauty and honesty. Perhaps photographers should allow their sitters to be more involved in the process. Maybe discussing where they would like to have their pictures displayed. Paying attention to consent not just when taking pictures but also for everything that comes after that.

NKDM: Nowadays, people often say we turn everything into a racial matter. Have you ever struggled to give the proper importance to race through your pictures?

KC: Absolutely not. Because I think race is everywhere in my work and in my life. I grew up in the American south so it is something I feel is very close to my history as a Black American woman. So yeah, it is important and I make sure it has the space it needs to be properly addressed.