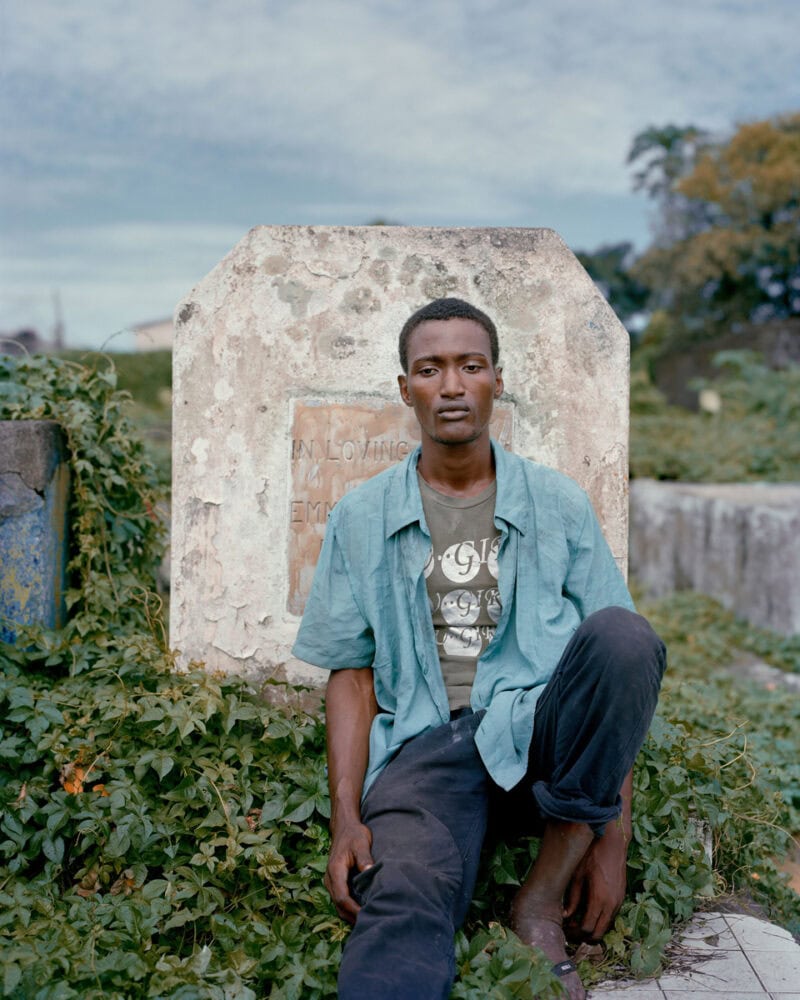

Born 1992 in Paris (France). Elliott Verdier is a documentary photographer. He grows up influenced by a « classical » photojournalism culture, but quickly questions his position as a witness and the subjectivity of his images. His work naturally steers away from hot news and favors the slowness of the large format camera. Driven by themes such as memory, generational transmission and resilience, he surveys territories and photographs with a certain intimacy, and dignity, the people who inhabit them.

In 2017, he completed his first long term project, ‘A Shaded Path’, in Kyrgyzstan. He was helped by the French National Center for Visual Arts in 2019 for his second major project ‘Reaching for Dawn’, in Liberia.

Elliott Verdier also collaborates with the press, especially with the New York Times, but also Le Monde Magazine and Vogue Italia.

About Reaching for Dawn – words by Elliott Verdier:

This is the story of a small piece of land nestled on the shores of West Africa, a long-neglected land of stifling mangroves, glutted with water and malaria, where the dense jungle sheltered a few isolated tribes. A land where, in the early 19th century, the government of the United States established, without ever naming it as such, its first colony. Baptized Republic of Liberia, bears in its name the cynical foundations of its adulterated history. At a time when an increasing number of former black slaves, now free and literate, appeared on the streets of the Union’s intellectual capitals, the white population felt challenged in its racial, cultural, and moral ideals. Nipping the problem in the bud, the decision was taken to ship off hundreds of brown-skinned men and women to this land that allegedly belonged to their ancestors. Impregnated with Christian and capitalist morals, the deportees became loyal agents of the US and reproduced a system that once oppressed them. The enslavement of the indigenous populations by the newcomers, prompting the putrefaction of post-colonial society and the negation of fundamental human values, fomented the tensions feeding the tragedy that has developed over the past two centuries, only to reach the epitome of savagery: the Liberian civil war (1989-2003). “The love of liberty brought us here”, the national motto, boasting local pride, is despairingly attached to a mystification erected on rejection, domination, and servitude.

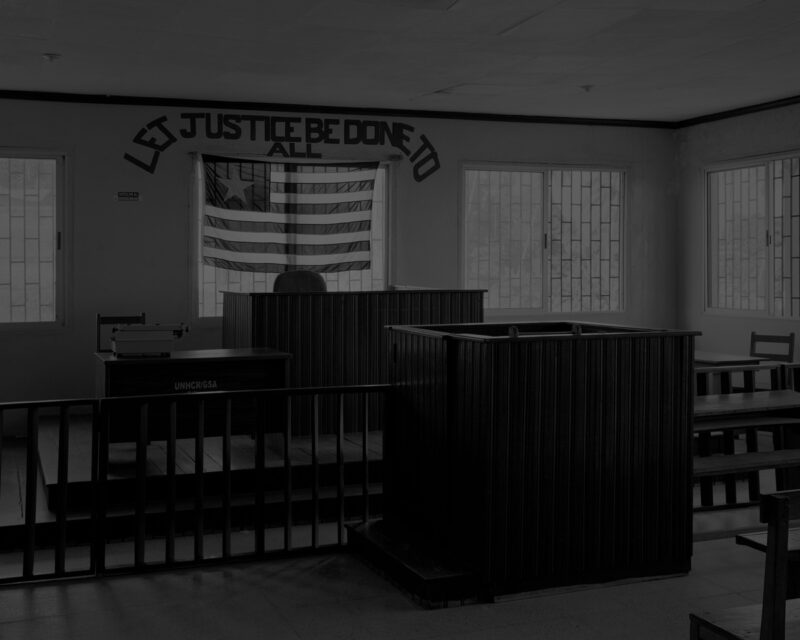

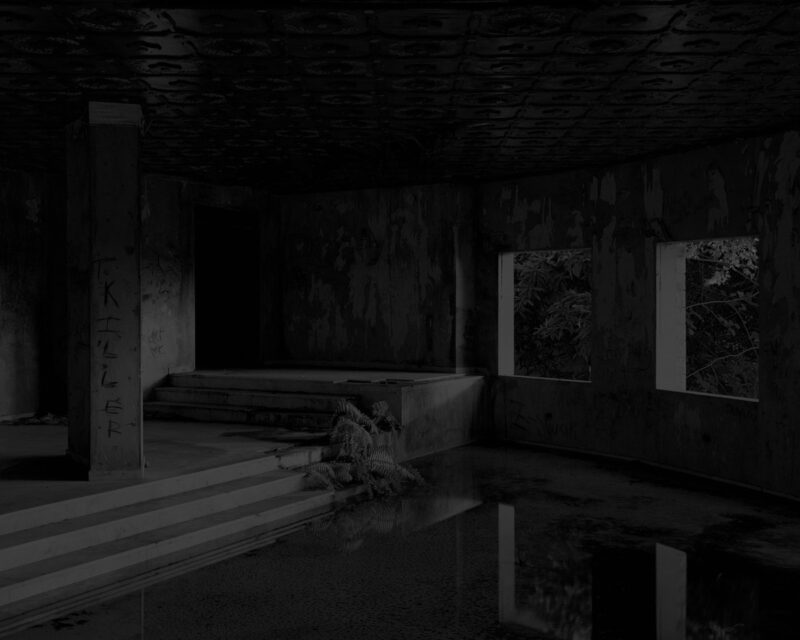

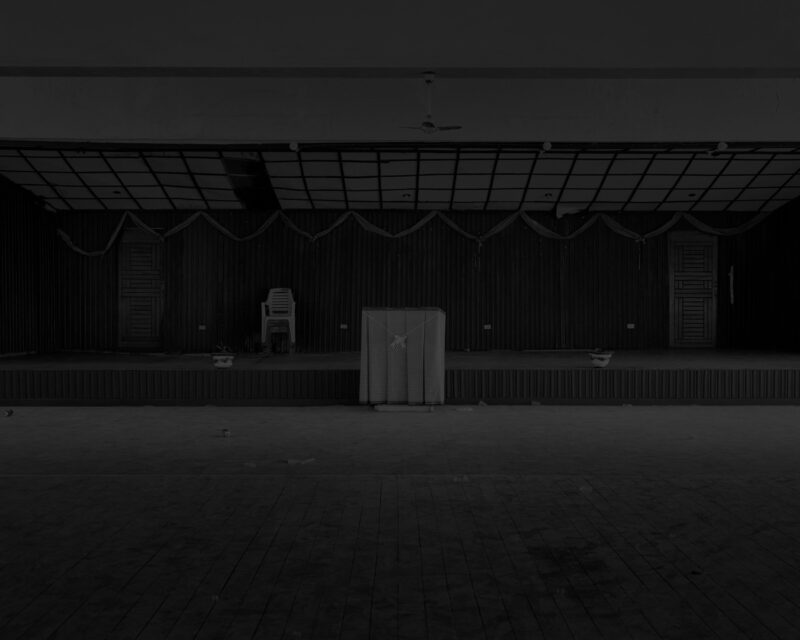

Of the bloody conflict that decimated Liberia, its population does not speak. No proper memorial has been built, no day is dedicated to commemoration. The country, still held by several protagonists of the carnage, refuses to condemn its perpetrators. Among them, Prince Johnson, former warlord, and infamous torturer, is now a senator, while the recently elected Vice-President is none other than Jewel Howard Taylor, ex-wife of war criminal Charles Taylor (only convicted for his crimes in Sierra Leone). This deafening silence, that resonates internationally, denies any possibility of social recognition or collective memory of the massacres, immuring Liberia in an endless feeling of abandonment and drowsy resignation. The trauma carved into the population’s flesh is crystallized in the society’s weak foundations, still imbued with an unsound Americanism, and bleeds onto a new generation with a hazy future. The wind of hope blown by the 2018 peaceful and democratic elections that put former ghetto child turned soccer star Georges Weah to power, is already falling through the cracks of his apathetic governance.

Liberia is suffering a long, anonymous night, a decaying sludge of existence miring pain and its innate loneliness. The photographic and audio work explores the mechanisms of its resilience and the invisible resorts of psychic trauma in war. Without Manichaeism, it unveils the eye and loosens the tongue of these women, these men, victims or perpetrators, on their damaged fate, made of nightmares in the daylight.