Eli Durst was born and raised in Austin, TX. HE received a Bachelor of Arts from Wesleyan University in 2011, majoring in American Studies and French Studies. After graduating, he moved to New York City to work as an assistant for photographer Joel Meyerowitz and as a fine art printer at the renowned photographic lab Griffin Editions. Durst returned to school to study photography at the Yale School of Art, graduating in May 2016 and receiving the Richard Benson Prize for Excellence in Photography.

While at Yale, he was the recipient of a 2015 Orville H. Schell Center for Human Rights Artist Grant to undertake a photographic project investigating the postcolonial legacy in Asmara, Eritrea. This series, entitled In Asmara, garnered him the 2016 Aperture Portfolio Prize which included publication in Aperture magazine and a solo show at Aperture Foundation in New York in 2017. In the same year, he was a recipient of an Aaron Siskind Individual Photographer Fellowship for his ongoing series The Community, which will be released as a monograph by London-based publisher Mörel Books in early 2020. In the summer of 2019, Durst received a New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) Artist Fellowship in the field of photography.

Durst is currently an Assistant Professor of Practice at the College of Fine Arts at the University of Texas at Austin. In 2019, he was awarded the John D. Murchison Fellowship in art in recognition of teaching excellence.

About ‘In Asmara’ – words by Eli Durst:

Asmara is unlike another city on earth. For a westerner, it seems to stand outside our conception of era and geography. Present-day Eritrea became an official Italian colony in the late 19th century. When Mussolini rose to power in the 1920s, he treated the colony’s capital city Asmara as a blank slate, tasking Italian Futurist architects to transform it into a fascist utopia. The city gained the moniker “Piccola Roma” and to this day contains one of the highest concentrations of modernist architecture in the world.

Eritrea, as a sovereign nation, is a relatively young country. After British forces expelled the Italian army from Eritrea during World War II, the UN ceded control of the land to Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia. A thirty-year guerrilla war for independence followed and in 1993, Eritrea officially claimed independence.

The optimism of the early 90s has slowly morphed into fear and dread, however, as Eritrea’s autocratic government never implemented the Constitution of 1997 that would have allowed multiple political parties to exist. As a result of the suppressive government, economic stagnation, and an indefinite national conscription program, tens of thousands of Eritreans are fleeing every year, seeking asylum in Europe or the United States.

I first became interested in Asmara when I realized that I knew nothing about it. My mother is an immigration lawyer in Austin, Texas, and many of her clients are Eritrean refugees. Since 2011, I’ve helped my mother with photo-related tasks, most of which involved taking blurry or pixelated cell phone pictures sent from foreign countries and editing them so they can be used for official immigration documents. Often, when I would tell my mother’s Eritrean clients that I was a photographer, they would tell me that I needed to photograph Asmara, and that it was the most beautiful city in the world. I was deeply struck by this seemingly paradoxical relationship to a space: a deep-seated love confronted by a desperate need to flee.

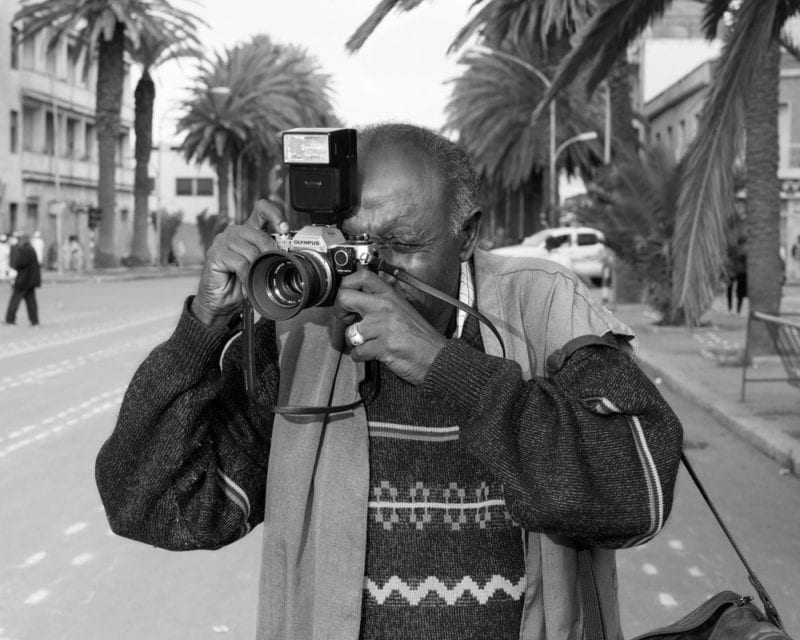

I was able to travel to Asmara during the summer of 2015 and these photographs represent an attempt to process the colonial legacy of this singular city and how it mirrors the repressive regime of today. Against the backdrop of Mussolini’s deteriorating Modernist masterpieces, Asmara sits at the intersection of a bygone vision of the future and the harsh realities of life in one of the world’s most troubled countries.