In the ever-evolving realm of photography, few names command as much respect and admiration as Coppi Barbieri. The dynamic duo behind the London-based powerhouse first crossed paths in Milan during the late 1980s, bonding over a shared passion for visual storytelling. Together, they embarked on a collaborative journey that would redefine the art of still life photography. Their ascent to prominence was meteoric, driven by a relent- less pursuit of excellence and an unwavering commitment to creativity. From their first steps at the Istituto Europeo di Design to their transformative move to the U.K., their portfolio boasts an impressive roster of clients, including Apple, Chanel, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, and Van Cleef & Arpels. However, amidst the glitz and glamour of the commercial world, Coppi Barbieri remains grounded in their artistic roots. Their early works from 1992 until 1997 offer a rare glimpse into the duo’s experimental phase, showcasing the raw talent and boundless creativity that would come to define their signature style. In this exclusive interview, photographic duo Coppi Barbieri (Fabrizio Coppi and Lucilla Barbieri) open up about their formative years, their unique process, and the philosophy that drives their work. Join us as we delve into their fascinating world, where imagination knows no bounds, and every image tells a story.

Nicolas Vamvouklis: Lucilla and Fabrizio, I would like to discuss your early work, so probably it would be better to start from the very beginning of this art and love story. Where did you first cross paths?

Coppi Barbieri: We actually met in Milan during the late 1980s at the esteemed Istituto Europeo di Design, commonly known as IED, where both of us were enrolled in the photography program.

NV: I am curious to know more about these formative creative years. How did your collaborative efforts begin to take shape?

CB: During that time, IED was becoming increasingly recognised as one of the best art and design schools in Italy, but it struggled to accommodate the growing number of students. As a solution, the faculty implemented a strategy to ensure all students could participate in the workshops. We were grouped into small teams, sometimes comprising just two or three people, and were tasked with sharing a single camera. We took turns behind the lens while our partners managed the logistics of the set design and lighting. This fostered a culture of collaboration among us all.

NV: Could you give me a glimpse of your inaugural studio where all the early photography experiments took place?

CB: Our first studio was located near Milan’s central railway station, within a 20th-century building close to Piazza Caiazzo. Situated on the fifth floor, our apartment was flooded with ample natural light. We converted the largest room, our living space, into a studio characterised by its generous proportions and pristine white walls. The interplay of light within this space bestowed upon our subjects a soft yet dynamic contrast.

NV: Reflecting on your nearly three-decade tenure in London, how has the city influenced your artistic trajectory? Do you ever find yourselves missing Italy?

CB: In 1996, we embarked on a bold venture, relocating to London to challenge ourselves creatively. London has always been very close to our vision and sensibility. Many magazines that published the type of photography we admired were based in London. Additionally, the music scene was also significant to us; most of the musicians we loved and still love were British. The city’s vibrant cultural landscape proved irresistibly appealing. London embraced us warmly, and we immediately received numerous commissions. British clients were very experimental, providing fertile ground for innovation. Recently, we’ve been working for Italian clients on a regu- lar basis, which has been an amazing experience to bring them our vision and collaborate with many inspiring creatives. Of course, we always miss Italy, especially its culture and beauty. While we cherish our Italian roots, our experiences in London have undeniably enriched our artistic perspective.

NV: While speaking, I am going through your book Early Works 1992- 1997, published by Damiani five years ago. It brings together all these incredible images you created together before your commercial career took off. I particularly appreciate the introductory quote by Plato: “The beginning is the most important part of the work.” How does this sentiment resonate with your process?

CB: The images showcased in this specific publication comprised the portfolio we took to London. They served, in a way, as our artistic compass during this transition period. None of these images were commissioned assignments; they all stemmed from personal exploration and embody our creative DNA. They provided a platform for honing our compositional techniques, mastering lighting nuances, textures, backgrounds, and colours. All these elements remain integral to our work today, forming the foundation upon which our subsequent endeavours were built. In essence, we could say that these images have refined our distinctive aesthetic and style.

NV: You have very often utilised ordinary domestic objects in your photography. I believe your mastery lies in transforming them into extraordinary works of art. What do you think defines a good still life?

CB: A compelling still life starts with an original idea, where commonplace objects are reimagined through a lens of creativity. We meticulously orchestrate compositions and lighting to elevate these objects, infusing them with a sense of monumentality and intrigue. The symmetry of the image and the low-angle view play pivotal roles in imbuing our still lives with a timeless allure.

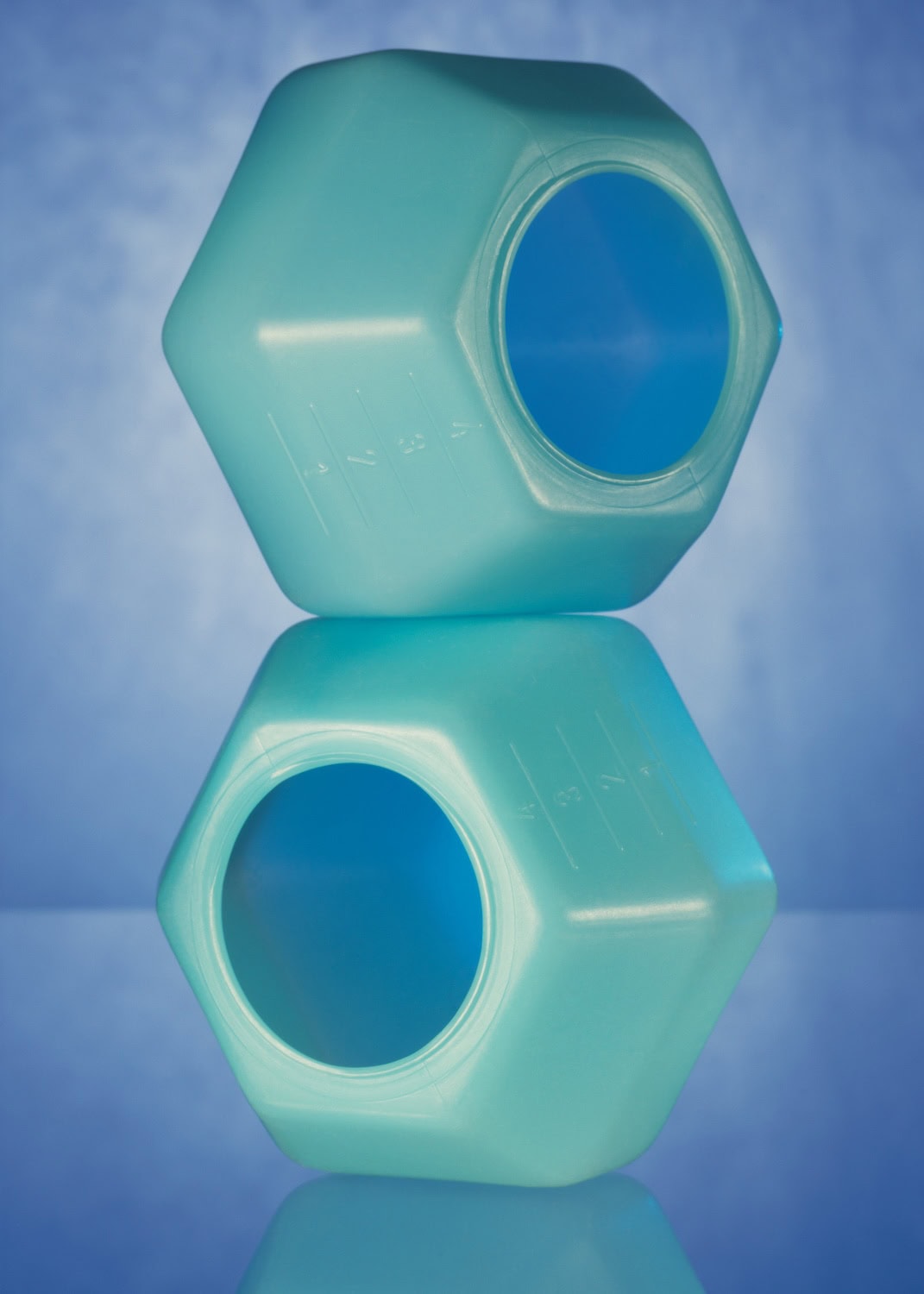

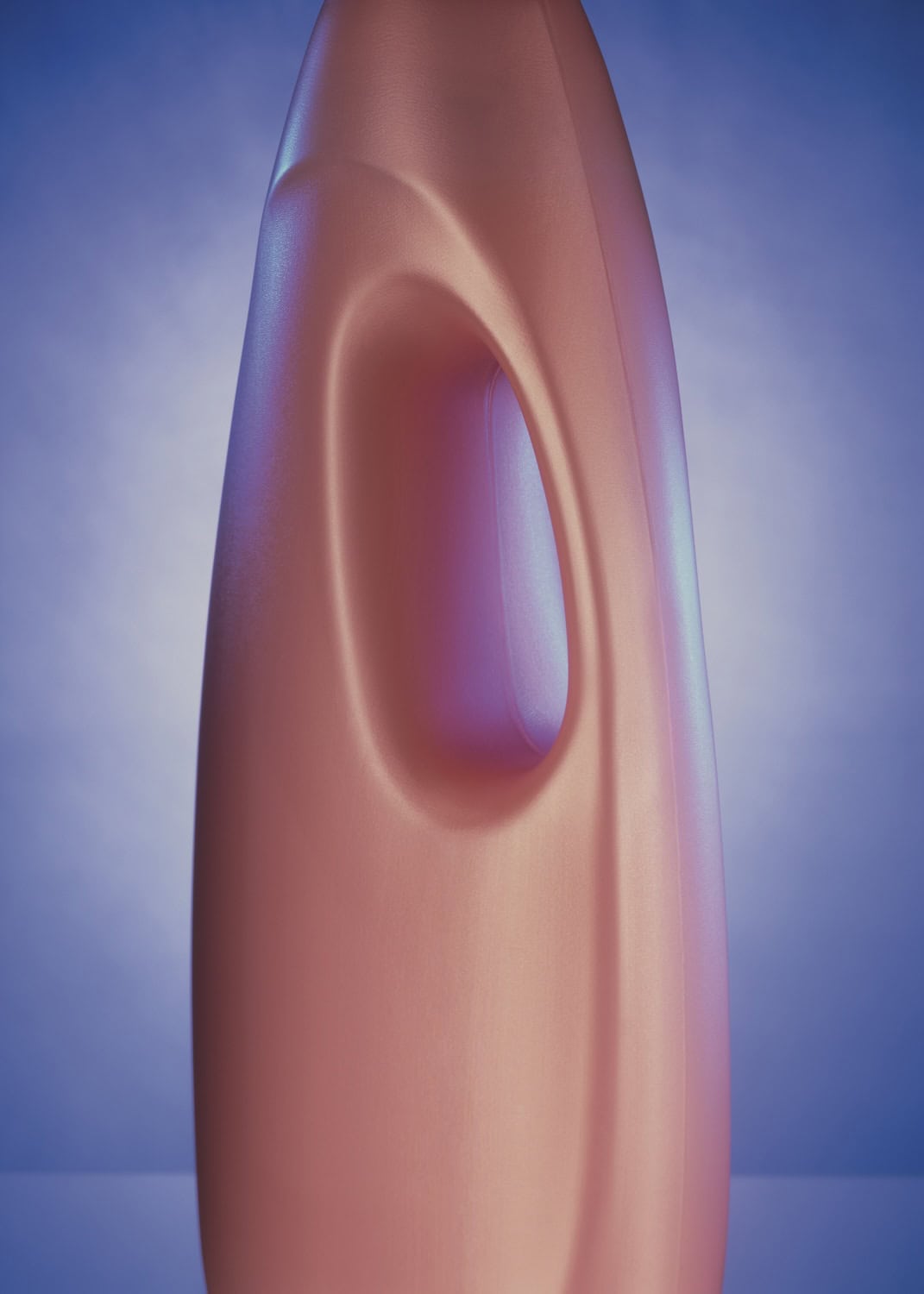

NV: Among your repertoire, my favourite series is the one featuring plastic detergent containers. I marvel at their sculptural volumes, and I also quite enjoy this juxtaposition of familiarity and grandeur. What drew you to these particular objects?

CB: Our fascination with simple, mundane objects stems from a desire to challenge perceptions and invite viewers to reconsider the ordinary. By spotlighting plastic mass-produced items, such as detergent bottles and iron water jugs, we offer a fresh outlook that transcends their utilitarian nature, evoking a sense of wonder and curiosity.

NV: Do you consider yourselves collectors in any capacity?

CB: We have a passion for glass objects that goes beyond mere accumulation. We keep whatever we accidentally break during the year, and at the end, we take pictures of these cracked objects. It is a sort of ritual that testifies to our commitment to creative exploration. We enjoy experimenting with the broken fragments, reimagining and reconstructing them into new forms.

NV: Photographer Paolo Roversi mentioned that your still lifes are actually acting as portraits. What is your take on this observation?

CB: We think that Paolo refers to our pictures as portraits because we treat the subject with the same attention one would give to a person. We infuse our still lifes with a sense of personality and depth: enhancing the best features, highlighting textures, sculpting shapes, and making the object akin to a sitter. Through this careful attention to detail, we invite contemplation and dialogue. We feel a connection with whoever dedicated time to designing this object.

NV: Let’s take a moment to delve into one of your signature techniques — the use of textile screens as filters. I imagine it is challenging to balance the result so that the objects will not get lost…

CB: The use of filters, particularly textiles placed in front of the lens, originated from our initial desire to “paint” with the camera. Textile filters imbue a sense of mystery and diminish certain aspects of reality, resulting in images that appear more dreamy and pictorial. We have extensively experimented with this technique and have mastered the ability to manipulate the degree of reality by employing various types of textiles, or even by utilising a sheet of glass dusted with powder in front of the lens.

NV: Speaking of visibility, if we were to remove Lucilla from a photo you two have taken together, what would be miss- ing? Vice versa for you, Fabrizio.

CB: It is difficult for us to say. It has rarely happened that we have shot assignments separately. Our process thrives on mutual respect and complementarity, with each of us offering a unique perspective that enriches the final outcome. In any case, the vision remains the same. Perhaps Lucilla likes to capture the object from above to highlight its fragility, while Fabrizio prefers a lower angle. However, the lighting techniques and sensibility would be very similar, as it is something we have developed together over the years.

NV: You started with a traditional large-format camera and gradually transitioned to digital. How has this shift affected your workflow?

CB: We began working with a 5×7 Sinar camera, shooting transparency film. The transition to a digital Sinar occurred relatively late, around 2008. It was a gradual shift, and at times, we still used film, especially for editorial and personal projects. We slowly learned to adapt to the new technology, recognising its amazing advantages. One challenge was maintaining the same contrast in our images as we had with transparency film. Today, in our opinion, it is difficult to discern a difference in our work between what was shot on film and what is captured with a digital camera. Working with film was a more intimate process. There were no large screens where everybody could see the images happening.

NV: I wonder, what is your relationship with social media? How do you approach these networks?

CB: We view social media as a powerful tool. We often use these platforms to highlight new projects and promote specific initiatives. Our content primarily consists of personal or editorial images.

NV: Your unique portfolio spans diverse genres, from fashion and beauty to food and car photography. What role does creative freedom play in navigating these varied landscapes?

CB: Creative freedom lies at the heart of our artistic ethos. We approach our commercial work as if it were our personal work and strive to remain true to our aesthetics. Collaboration is key and fuels our process; a great creative director always assists in making a better picture.

NV: What are you currently working on? Is there any exciting new project on the horizon that you would like to share with me?

CB: At present, we have been working on a personal project for several years. It is titled PLUMAE and it is an extensive study on the plumage of live birds. The images consist of close-ups of the birds’ feathers, showcasing joyful patterns and fantastic colours that form harmonious abstract textures, sometimes reminiscent of aerial landscapes. The birds have been sourced from private collections throughout the UK or bird sanctuaries. It is interesting to observe how different species exhibit different personalities. Some, like pheasants, are really easy to photograph with a handler. Birds of prey readily pose for you, while parrots are temperamental and quite challenging. We envision the project evolving into our next book and an exhibition, offering audiences a captivating glimpse into the diverse world of avian beauty.

NV: This sounds very intriguing. Well, if you weren’t photographers, what do you think

you would be?

Fabrizio: Today I would probably say architect, although I must admit this did not cross my mind in my teenage years.

Lucilla: Astrophysics was my only passion in my youth.

NV: There is this question from the Proust Questionnaire I would really like to address to both of you. Which talent would you most like to have?

Fabrizio: I am quite impatient and therefore I would like to deal with matters more calmly.

Lucilla: I would like to take things more lightly and remember that often when people express judgement, they are talking more about themselves than about you.

NV: To conclude, what advice would you offer to emerging photographers just starting out?

CB: Aspiring photographers should take the time to develop a unique vision and a recognisable style. This style should evolve over time but remain coherent. Always remember, success doesn’t happen overnight; it’s the result of consistent effort and many small steps.