I’m not a photographer, but I can be one.

With this disarming and unapologetic statement, Enrico Rassu opens our conversation. A lucid, deliberate refusal of labels, and a gateway into a layered meditation on artistic identity, the archive as an emotional dwelling, and the deeply human urge to exist beyond all forms of classification. The interview gradually unfolds into the realm of books — two distinct yet intimately connected works, like pulsing veins of the same body. Both span nearly a decade of crossings and encounters, and reveal a rare and radical stance: that of someone who doesn’t shoot to build an image, but to honour a moment.

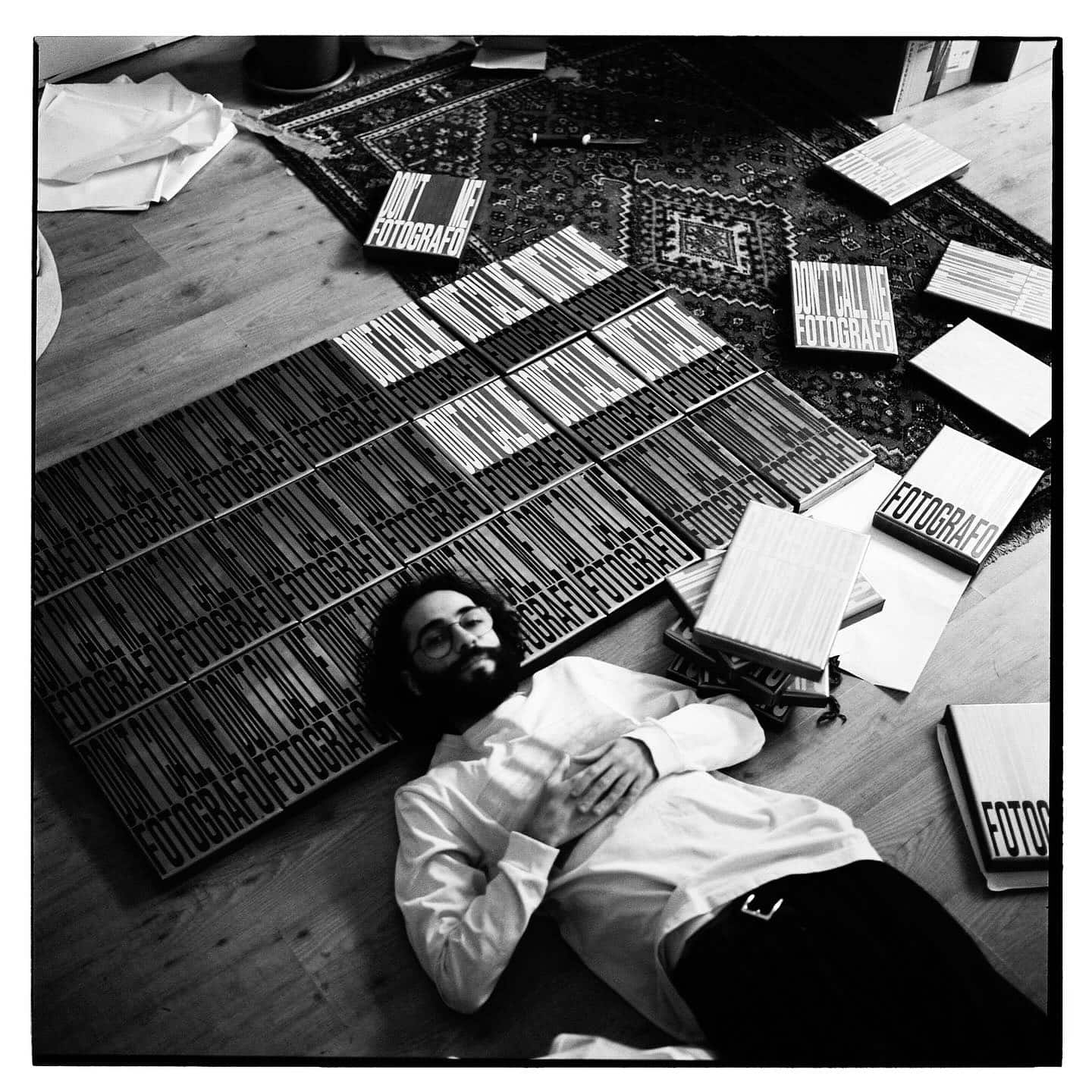

The first book is not for sale. It’s a sealed object, complete and finite, which Enrico describes in striking, almost funereal terms:

“It’s a tomb. A piece of metal engraved with 2017–2025 Enrico Rassu.”

This “tomb” isn’t an epitaph, but an affective container. First presented at Art Basel, in a presentation curated by WUF (We Understand Future), the book entered the public eye not as a commodity, but as an intimate, finite gesture. An archive of steps, faces, places traversed. Not just a photography anthology, but a ritual gesture — both burial and care. The images — some of which portray well-known figures, scenes from the art world, friends — are not declarations. “They are where I walked. Who I met. What I saw while I was there.” It is in this affirmation that one of the deepest aspects of his practice is revealed: the book is not an object to be read, but a space to inhabit. Not a linear narrative, but an emotional and sensitive landscape. A place to lose — or find — oneself in silence.

RITAMORENA ZOTTI: The title Don’t Call Me Fotografo is a bold stance. What exactly are you rejecting in that word?

“One word is never enough,” says Rassu with the calm of someone who’s dwelt in the grey areas of meaning, emerging with a quiet clarity. “It takes twenty, thirty words. At most, what we do can shape us — but not one word.”

His tone carries both the assurance gained over time and the embrace of doubt as a form of freedom. Rejecting the term photographer is not a quirk, but a necessity — a desire to protect the complexity of being from a label that flattens and confines. In a time of simplification and categorisation, Rassu invites us to slow down, to name with care, and to treat the margins as fertile ground. His work isn’t a job description — it’s a way of being.

RZ: Your work moves across images, stories, archives, and communities. How would you define — if you ever wanted to — your practice?

“I’m Enrico, if you want. I decide to take a photo, to organise an event, to become someone’s friend, to be a son, to be a thing.” His practice is a continuous motion, never fully classifiable. A gesture rooted in encounter, in the moment, in the fertile stumble. Identity and profession break apart to become daily choices. The self becomes a space of relation, where every act is openness, possibility, question. This is a radical vision of selfhood, rejecting the verticality of authorship in favour of fluidity.

RZ: How important is it, today, to free oneself from professional labels? And how can that freedom avoid becoming just another pose?

“For a long time I saw my passions as a weakness,” I admit, in that rare suspension between interviewer and interviewee. Enrico smiles with the gentleness of someone who doesn’t need to explain everything to be understood. In a time obsessed with output, performance, and hyper-specialisation, letting go of labels becomes both resistance and care. But it’s not easy: “Sometimes it does feel like a pose, I know. But if you really mean it, it changes everything.” The point is not to turn refusal into an aesthetic, but to hold space for an ethic of presence.

RZ: The photographs in the book span nearly a decade. Looking at them together, what kind of story emerges?

The book is a tomb, a body, a stretch of time made touchable.

“A tomb, a piece of metal engraved with 2017–2025 Enrico Rassu,” he says. It’s not a publishing product, but an existential container. A place to inhabit rather than sell. It gathers encounters, walks, intuitions. The photos are traces — footsteps in the worlds and lives of others. The book is an object to leave behind, not to distribute. An intimate legacy, an affective archive, a gesture of love.

RZ: Is there an invisible thread connecting the photos you selected for the exhibition? A theme that revealed itself while looking back at your archive?

There’s no imposed narrative, only an emotional necessity running through every image: the need to preserve. Not to hold on, but to be able to reread. To remember who we were, who we’ve been for others. The archive is not static; it’s a body in flux. It becomes an exercise in memory, a space of resonance. In each photo, the desire not to lose — or perhaps, to lose oneself with others, but consciously so.

RZ: How important are context and timing when you shoot? Are you more interested in documenting or interpreting?

“There’s no rule. Sometimes it’s a need for closeness, sometimes it’s just curiosity.” Photography, for Rassu, emerges from the gesture, not the project. It’s a way to get closer, to acknowledge, to touch.

Context often comes after the fact — and most often, it’s the emotion that drives the click. A graffiti, a face, a presence: Enrico follows, listens, captures. Not to document, but to be with.

RZ: Many of your subjects are recognisable figures in music and visual culture. What guides you when taking a portrait?

It’s not fame that draws his lens, but energy — the enigma. “I want to know who you are. Or rather: who you are while I’m looking at you.” The image becomes the result of an encounter, never its representation. The goal is not to possess, but to welcome. To look without trying to define.

RZ: Do you have a method for creating connection with your subject? Or do you prefer to leave space for spontaneity?

No method — just presence. If the encounter is genuine, it happens on its own. “It’s like falling in love: you can’t control it.” Enrico doesn’t direct, doesn’t force, doesn’t stage. He stays. He waits. He lets himself be surprised.

RZ: Is there a photo, a person, or a meeting that changed your way of seeing things?

“Rosa’s pills,” he replies without hesitation. The project began with Rosa, a girl he met in Florence. In New York, at her home, Enrico noticed a blanket painted with all the psychiatric medications Rosa had taken between ages 15 and 21. She was inspired by Warhol’s soup cans — the same ones her mother served her during her darkest moments. Adderall, sleeping pills, mood stabilisers: every colour told a story. “A statement, a protest,” he says. A necessary work. Rassu brought the project into Angelini Pharma and helped shape an artistic and political dialogue. But he also felt the need to return Rosa’s story to her complexity — to tell it her way, with respect, beyond any institutional filter. An encounter that changed his idea of care, art, and relationship.

RZ: How did No Ball Games shape your approach? Is it just a collective, or something more personal?

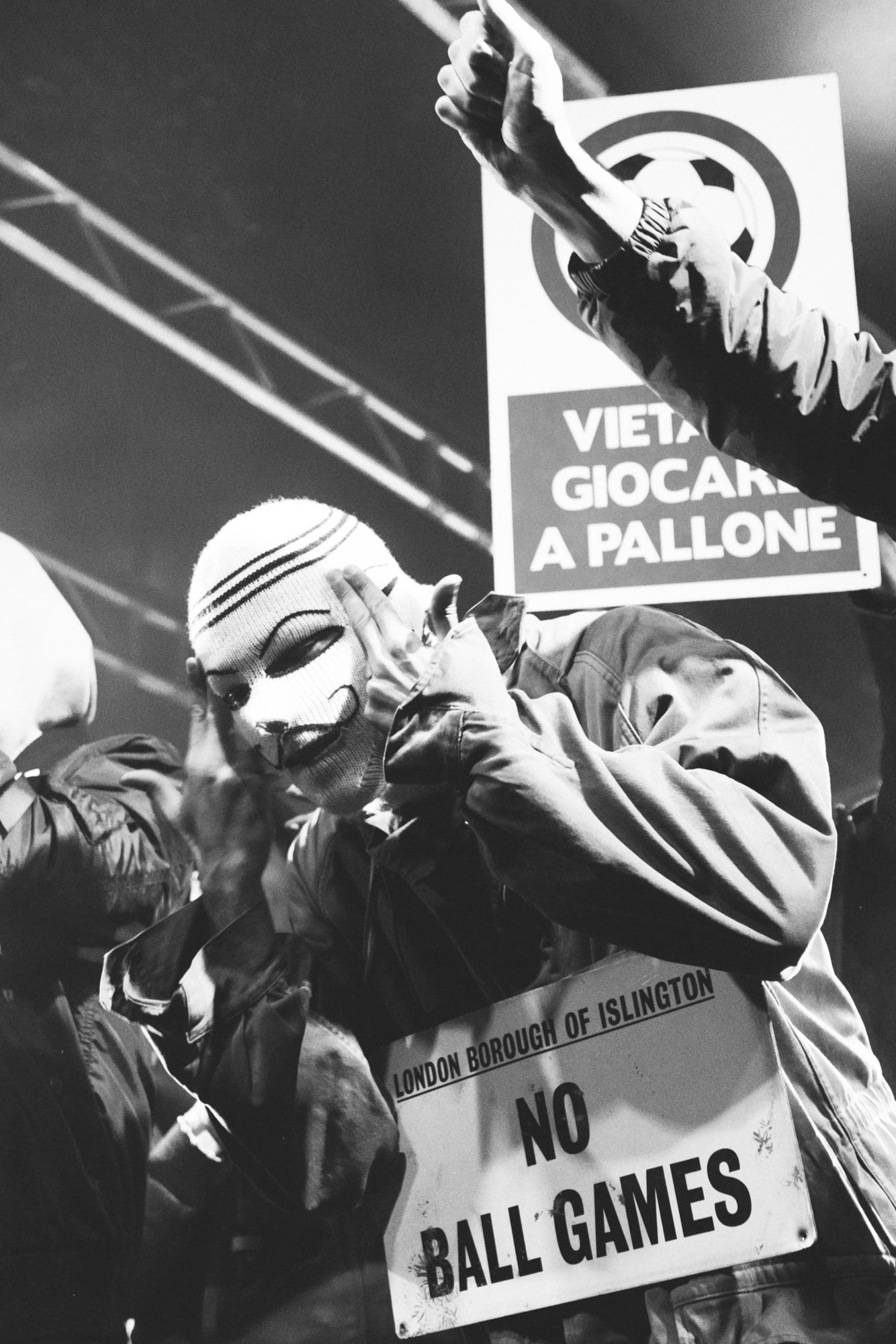

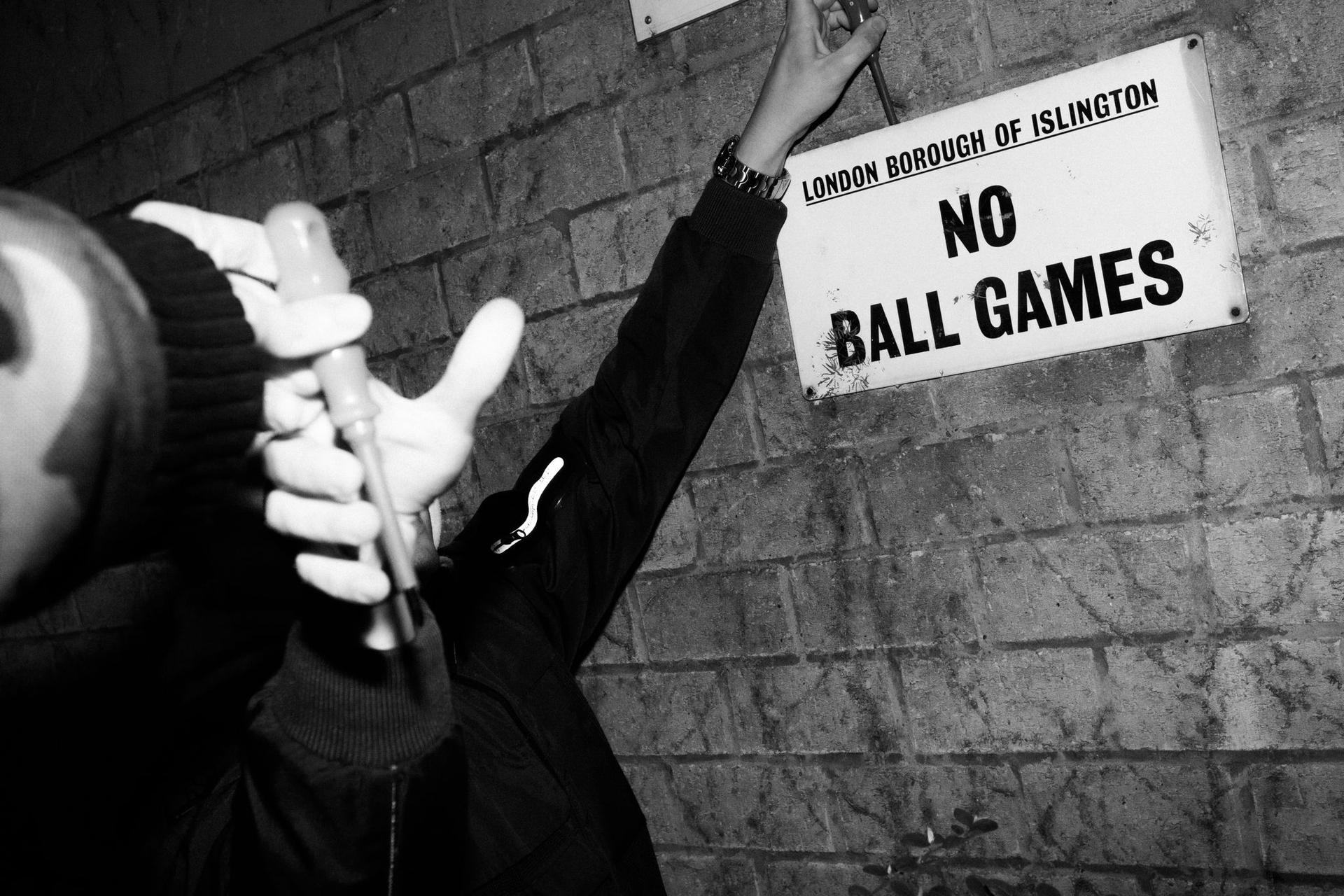

It’s personal, political, and deeply poetic. No Ball Games is a declaration of love for desertion, non-production, and non-performance. A collective gesture that refuses imposed order in order to open up spaces of freedom. One of the most powerful events — with no schedule, no RSVP, no names — embodied a tangible utopia. “People could be whatever the f*** they wanted.”

A temporary, loving, radically free community.

RZ: “We are not what we do” is the phrase chosen for the mural installation. Is it a provocation or a necessity?

It’s a necessity — almost a silent scream.

“People need to hear that,” he says. In a world that constantly asks what do you do?, the answer is a refusal: we are much more than what we produce. It’s an invitation to remember we are alive — beyond all roles.

RZ: This seems more like a collective declaration than a traditional presentation. How did you approach the direction of the entire thing?

Enrico doesn’t direct — he orchestrates. He lets things happen. He listens, invites, connects. The short film — which reveals a vulnerable part of his past — was made not for the screen, but for a collective experience. The mixtape plays with fragments and echoes from a long emotional journey. The performances are moments of activation — ephemeral and relational. It’s not an exhibition, but a place of shared presence. An invitation to stay a while. To inhabit the archive as a body. To exist outside of the frame.

RZ: What kind of experience do you want to offer the audience? What do you hope remains, beyond the images?

“I’d like people to feel less alone. To leave with a question, maybe. Or with a desire.” For Rassu, art is never an object. It is a relational space. It is openness. It is the echo of an encounter that continues even after the exhibition.

RZ: What role should the artist have today, in your opinion? More than documenting or representing — acting, perhaps?

“Doing things to feel good. And in doing so, making others feel good too.” The answer disarms with its simplicity, and precisely for that reason, it overturns everything. The artist as healer, as sower of kindness, as witness to a time that can still be loved. You don’t need to be special. You just need to be present.

In the end, this work is an attempt to stay.

To stay in places, in bonds, in bodies. Even if only for a moment.