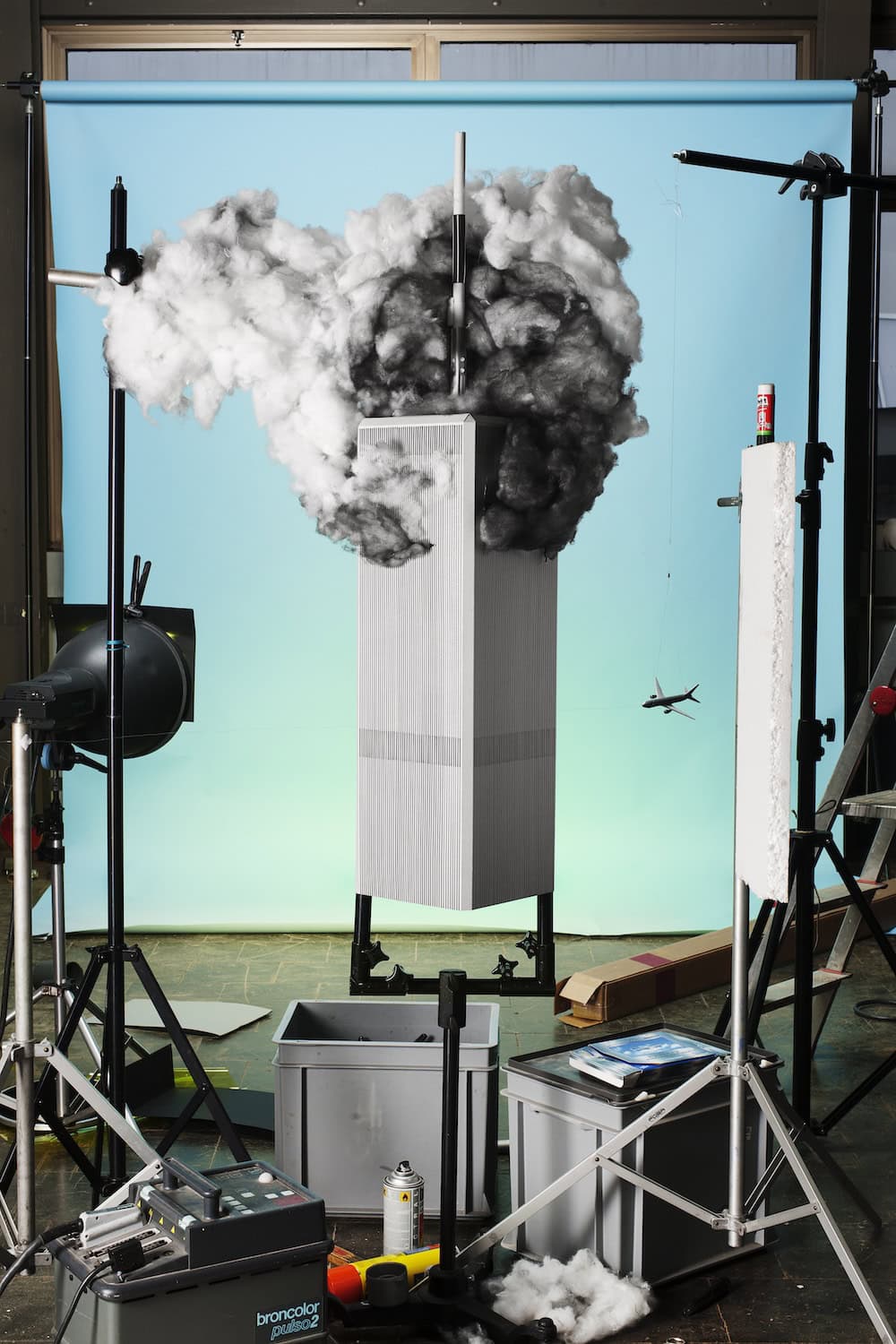

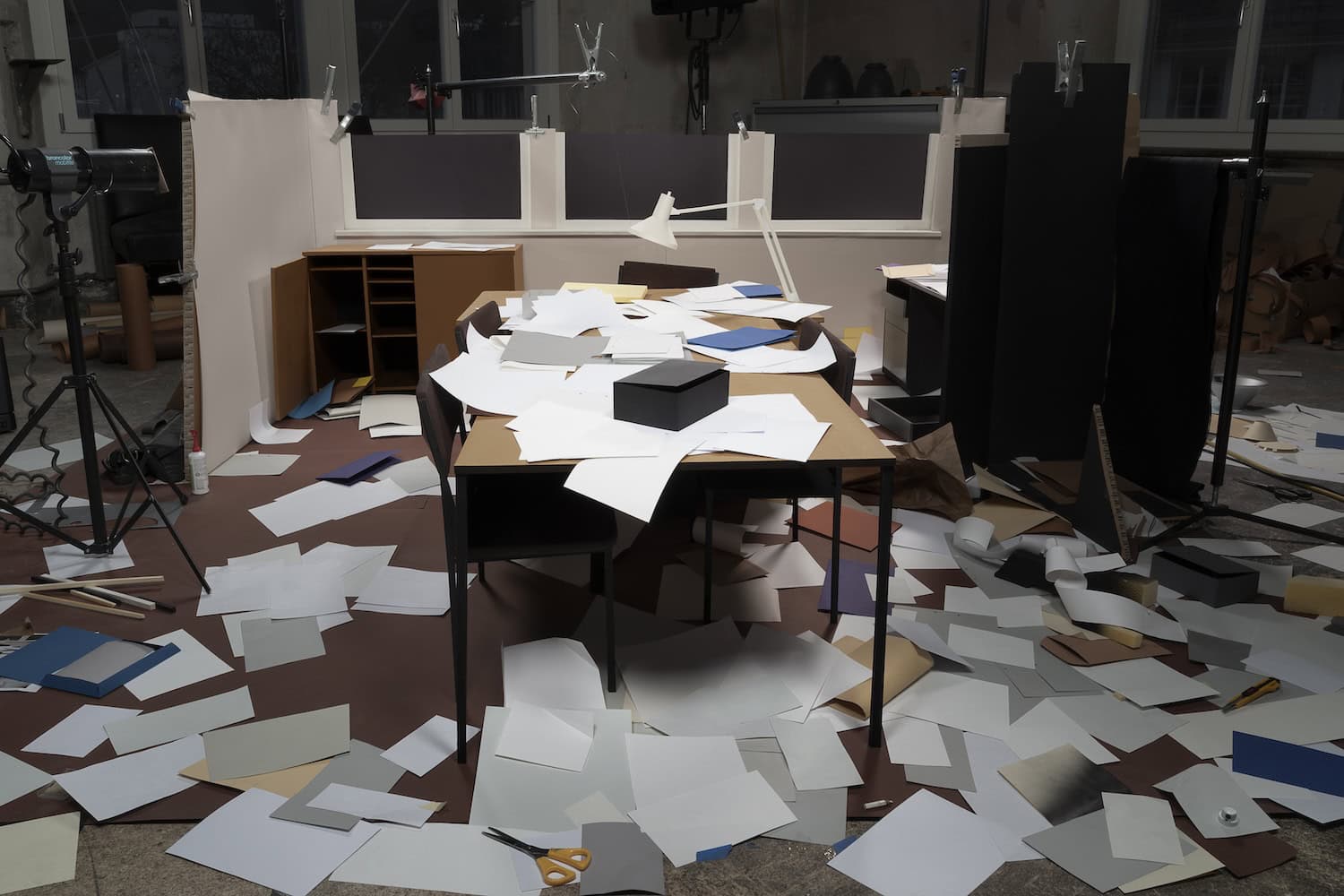

Since 2012, artist duo Jojakim Cortis (b. 1978, Germany) and Adrian Sonderegger (b. 1980, Switzerland), otherwise known by their shared name Cortis & Sonderegger, have been constructing exhaustive dioramas (a three-dimensional theatrical model) by hand of iconic photographs that balance between truth and fabrication. Photographs such as Robert Capa’s Falling Solider, Ansel Adams’ Moon and Half Dome, Joe Rosenthal’s Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, and Stuart Franklin’s Tiananmen Square are all etched into our collective memory and consequently have all been recreated by Cortis & Sonderegger. After each scrupulous scene is made, the pair photograph their creation including the materials, tools, structures, and lighting that have conceived their trickery in the frame. By exposing their activities, the duo allows us to examine where the boundaries lie of perceived reality, how fiction can work in tandem with truth, and what authenticity is in the photographic medium.

Ilaria Sponda: How did you start as a duo? What are your backgrounds?

Jojakim Cortis & Adrian Sonderegger: We met at an art school in Zurich and became friends because we had similar interests in art and music. We started studying photography in 2001. At the end of our studies, around 2005, we started working together. In 2006, we did our diploma thesis together, which was about places that simulate something. It was a classic documentary work with a large-format camera. We also wrote our theoretical paper on artist couples and their collaboration. Your creative outputs are extremely staged, so I was wondering how much of your creative process is also rooted in fiction, or if you get inspiration from any fictional world. Our creative output is very staged. One of the main reasons why we are very much anchored in staged photography is the fact that there are two of us. We talk a lot about image concepts at the beginning before we ever pick up the camera. As a result, our way of working is very controlled and inevitably staged. It’s difficult to say exactly where we find our inspiration. Jojakim watches a lot of movies, while Adrian goes to see more exhibitions. But a lot of things flow into our work very unconsciously.

IS: How did Icons come about?

JC & AS: The Icons series began in the summer of 2012. Before, we were primarily focused on editorial work and didn’t have much time for freelance projects. In that summer, things were quiet with no assignments coming in and not much money, so we decided to take on a freelance project. We had the crazy idea of recreating the most expensive photos in existence in three dimensions. Thus, we made a miniature replica of Rhine II by Andreas Gursky while maintaining every detail from the original photo. However, simply copying it wasn’t interesting enough for us. We took a step back and photographed the environment of our studio, including the tools and materials we used. We quickly realized that this was much more exciting than just reproducing a section of the original photo. As we continued with the project, we found it difficult to reconstruct other expensive photos, as many of them featured people or close-ups of faces. Therefore, we shifted our focus to famous photos that hold a place in our collective memory.

IS: Given the current lack of trust in images, do you believe that photography has lost its role as a means of representation?

JC & AS: The act of taking a photograph begins with the decision to capture a specific moment, neither a second earlier nor later. It is then followed by the choice of framing, as each photograph inherently has its limitations. What lies beyond the edges of the picture? Only the person behind the camera decides what to include or exclude. In this sense, photography only offers a fragment of reality and should never be seen as completely authentic. The credibility of photography has never been absolute, as image manipulation emerged alongside the development of photography itself. The advent of digital photography in the 1990s introduced new methods of manipulation that we are all familiar with. Today, with the advancement of AI, it is possible to create entirely synthetic images that have no connection to reality, challenging the truthfulness of photography. Therefore, it is crucial to clearly distinguish between these generated images and authentic photography. However, it is also advantageous that traditional documentary photography can still claim authenticity.

IS: What is your relationship with AI? Have you been testing it?

JC & AS: In principle, we actually do the opposite of what AI does. The handmade and analog nature is extremely important in all our photographs. However, we are very interested in technology and what can be achieved with AI. That’s why we have been conducting some experiments to explore how we can integrate this technology into our work. Of course, we also recognize the potential risks associated with AI. Photography is losing its credibility to some extent. However, there was a similar outcry when digital photography first emerged. Ultimately, it is up to the viewer to exercise skepticism and question every image they encounter.

IS: What role, if any, does irony play in your work?

JC & AS: Irony plays a significant role in our work. Even though the theme of the work Icons is serious and often sad, we incorporate irony and humorous elements. It is a strategy we use to approach somber subjects with humor. The title Making of… for each picture is meant to be understood with a light-hearted tone, and it does not imply that we took the original photographs.