Circ Studio is an architecture and interior design practice that embraces the unexpected, balancing a playful imagination with an eye for detail.

With the motto “Wandering, wondering, and daydreaming” as their compass, the studio frames design as an open invitation to step outside the ordinary. In their own words, they are “dedicated to (…) architecture beyond the high-rise towers and the known.”

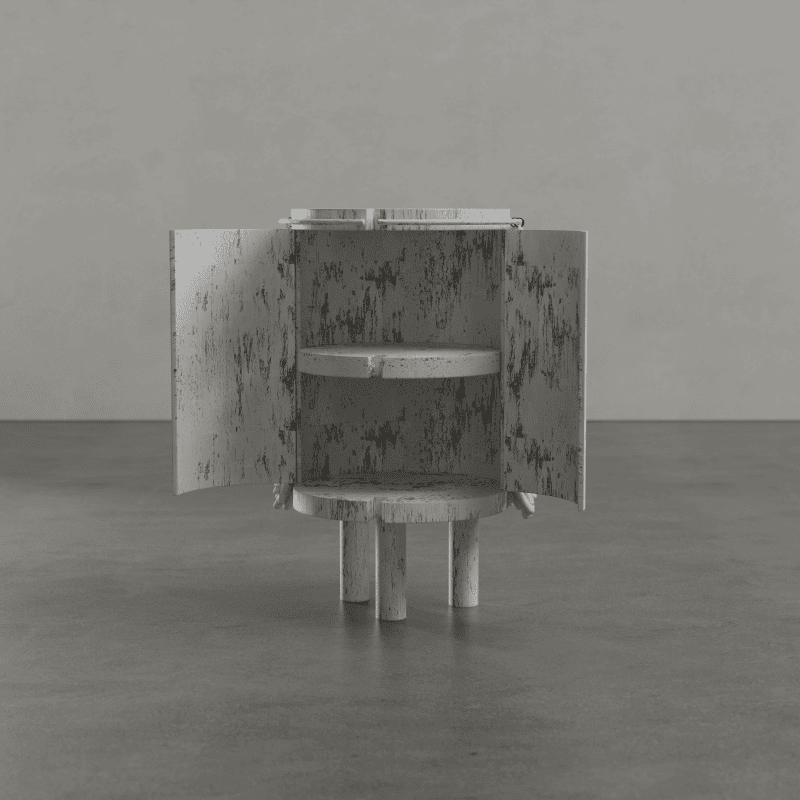

Founded by Sara Bokr, this UAE-based studio shifts effortlessly between scales — from designing objects like the Tabi Rack to shaping interiors such as a smash room — always searching for new ways to turn space into an experience.

Nisha Kapitzki: What drew you to architecture in the first place? Was there a specific moment or influence that shaped your path, or a first building or space that made you want to become an architect?

Sara Bokr: Honestly, I don’t think there was one single moment, it was more of a slow intuitive pull. I’ve always loved making things and assembling objects with my hands. That love for creating and making naturally evolved into an interest in architecture. I wasn’t very aware of buildings in terms of their shapes or forms when I was younger, but I was aware of how they made me feel. I could remember the emotion a space carried, whether it made me feel safe, happy, or even unsettled. That emotional awareness of space is what lured me in and made me want to shape those feelings for others.

NK: What is your creative process like?

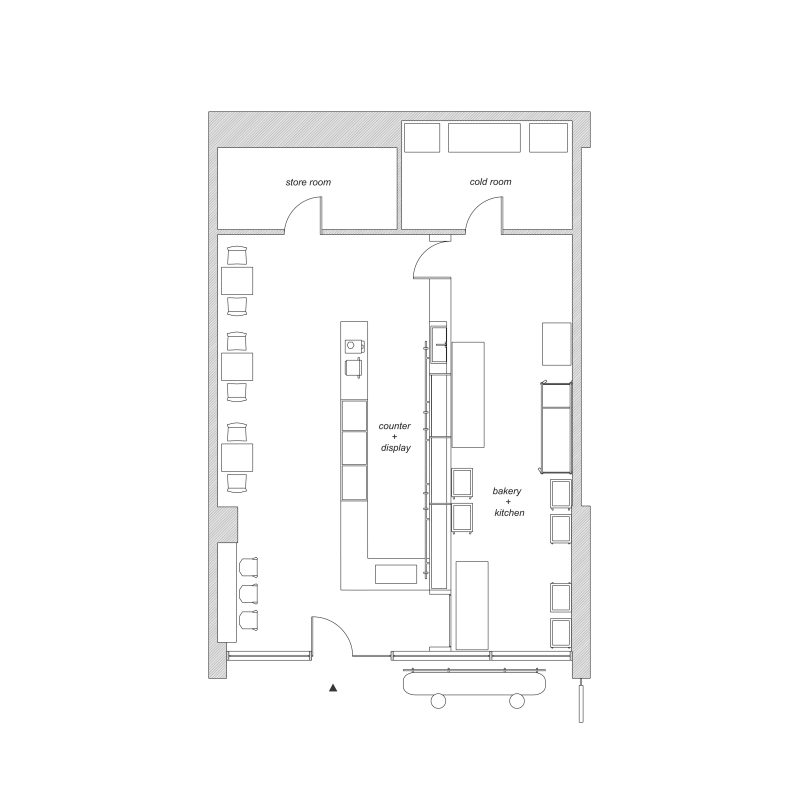

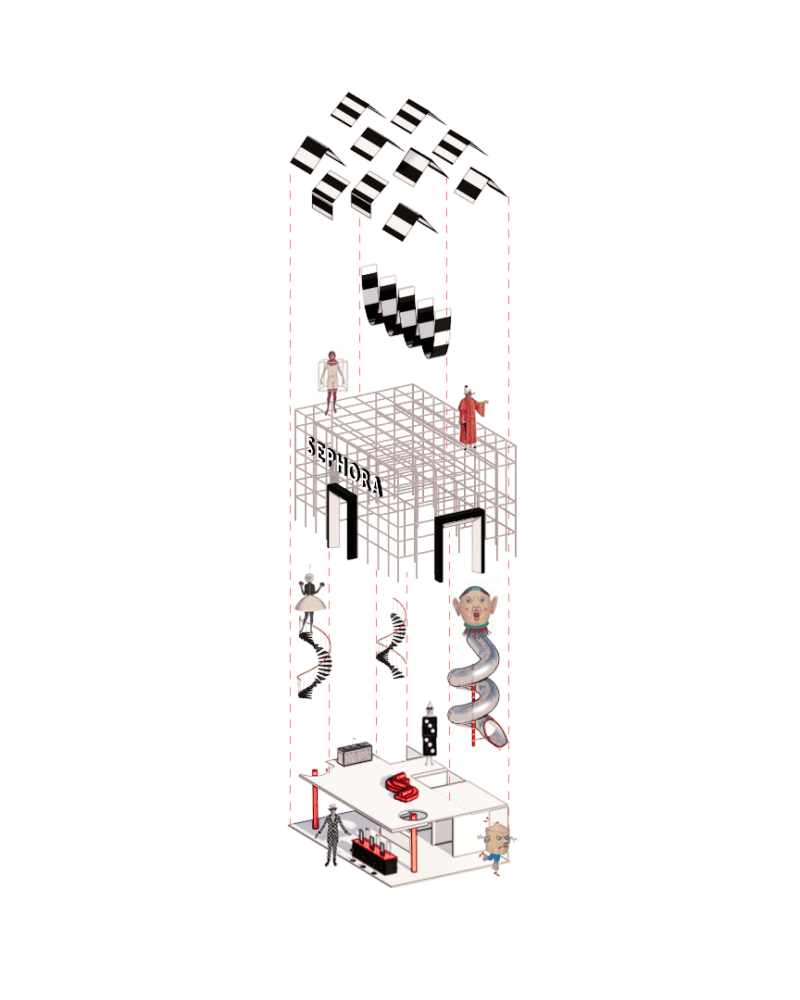

SB: It always starts with a lot of daydreaming. I find myself constantly visualizing and mentally playing with the projects I’m working on. It becomes a mix match situation, which happens before I even put anything down on paper. But it usually begins with a little sketch. Paper and cardboard are my go-to materials for making my quick 2-minute study models. I then move to 3D modeling to understand how the structure can come to life in space, colors and materials. Once that feels right, I get on to the technical drawings to detail the concept

further.

NK: How has your relationship with space changed since becoming an architect?

SB: Since becoming an architect, my relationship with space has completely shifted. The way I see details is as if I’m looking at them with a magnifier. Things I never noticed before have become part of my everyday life, almost without realizing. Suddenly I am understanding why the kitchen table brought us together for lunch at my parent’s house, while the dining table in the living room didn’t. I’m hooked on the subtle cues in a space that influence how we behave and connect. Now I’m constantly touching walls, running my hands over chairs, getting up close to see the hinges behind a good door. It’s like I can’t move through a space without needing to understand how and why it works the way it does.

NK: Is there a project or design of yours that feels particularly personal to you?

SB: Omooma chair is one of my most personal projects. I’m not a mother, but I wanted to understand the emotional weight of motherhood and nursing in that phase. Omooma became a way for me to explore that kind of care through design. After it was mad, I thought about when I’ll become a mother myself, and how I’ll immediately revisit that chair when I’m nursing—and maybe redesign it.

NK: How do your personal values show up in your work, even in small ways?

SB: My personal values always push me to leave behind formal by-the-book methodologies. I care more about offering an experience, whether it’s through something absurd, a fix, or an idea that needs attention. I want people to feel something, even if it’s stupid or unnecessary. That reaction means it did its job. Through my own practice Circ Studio, that ethos becomes a design language.

NK: When you’re starting a new project, where does your mind go first—form, feeling, site, story?

SB: It depends. Once I understand what needs to be addressed, whether it’s functionality,

emotional value, or spatial attributes, I start to explore how form, story, and feeling can grow out of that. I need the why first. That’s how it works at Circ Studio—we don’t rush into what it should look like, but we start by figuring out what it needs to do or say. Once that’s clear, everything else starts to take shape naturally.

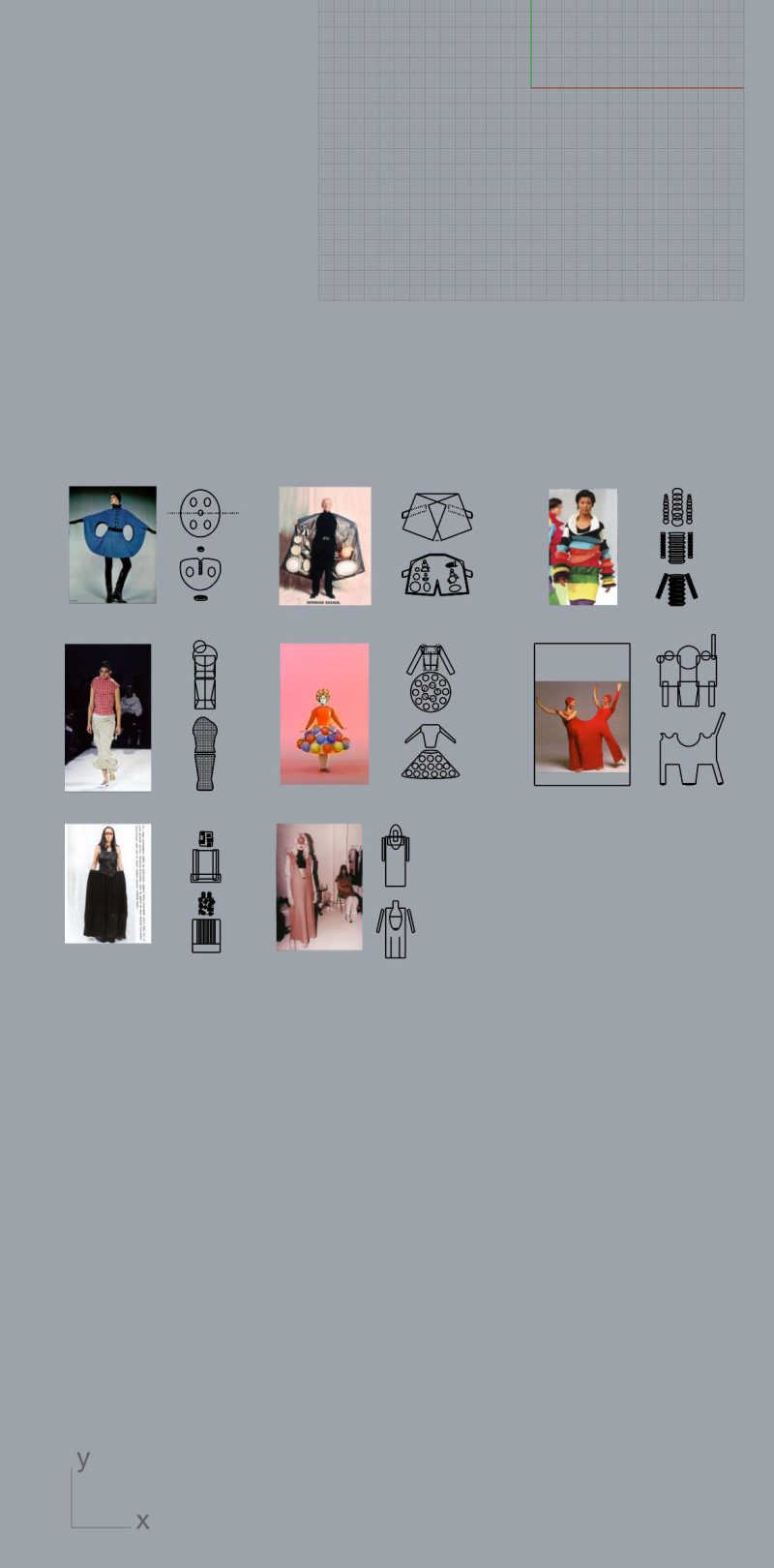

NK: Does inspiration ever come more from outside your discipline—like from film, fashion, or nature?

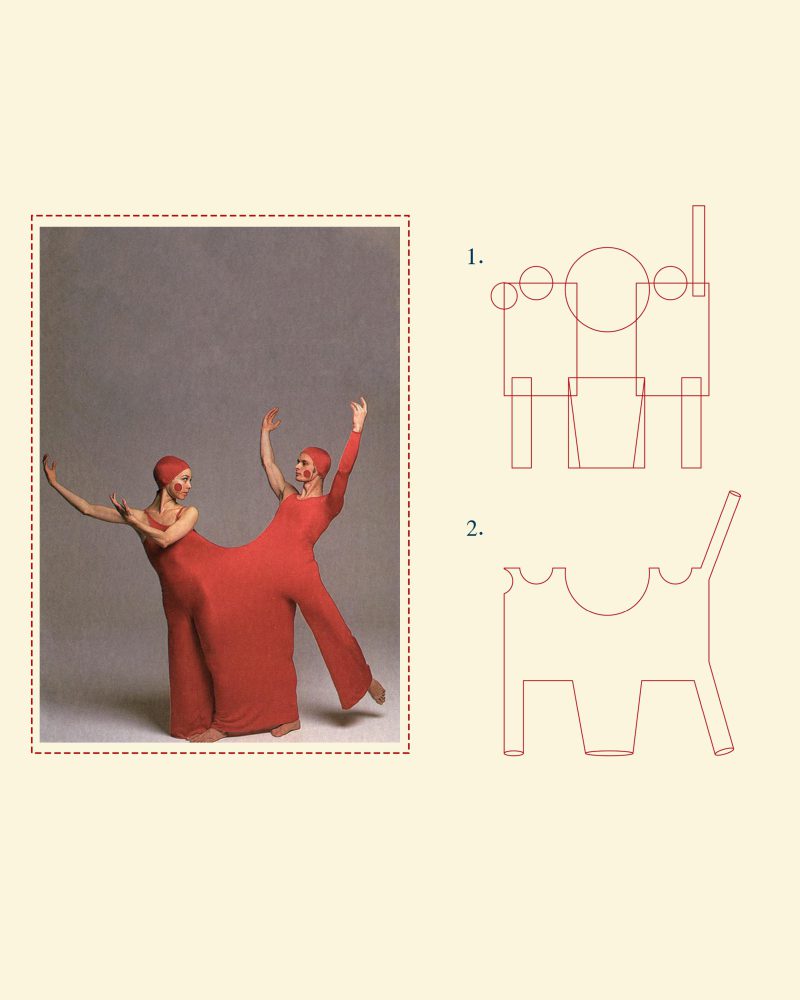

SB: Yes. I’d say that in terms of scale, if you magnified film, fashion, or music, they’d all start to feel a lot like architecture. The layers, the structure, the way they trigger senses or follow certain mechanisms—it all translates. I get just as much inspiration from a garment’s construction or a scene in a film as I do from a building. It’s all spatial in its own way.

NK: Have you ever collaborated with artists or technologies in unexpected ways?

SB: Almost every project ends up being a collaboration, if I really think about it. Whether the person I’m working with is a DJ, filmmaker, artist, or even a finance bro, it’s still a creative exchange. I get to understand how their mind works and how mine responds to it, and somewhere in between, we shape something that feels relevant to both of us. That back- and-forth is what makes the process intertwined.

NK: How do you measure the success of a building years after it’s built?

SB: I measure its success by how it stays with you, if you still remember how it made you feel even after you’ve left it. That emotional imprint and the timelessness mean more to me than the methodology it followed. If the space still holds meaning years later, then it worked.

NK: Which overlooked buildings or architects do you think deserve more recognition?

SB: I think overlooked buildings are often the most unforgettable. Some of my favorites are in Sharjah and Bahrain, like the Flying Saucer and the House of Music. They both have stories embedded in them and are tucked into the older parts of the city. There’s something theatrical and new in how they hold space and emotion. They leave a mark without trying too hard. Those are the ones that stick with me.

NK: What is something you wished more people knew about the art of architecture as well as a profession?

SB: That architecture can be absurd, theatrical, emotional, and even temporary. It doesn’t

have to be permanent to be powerful. Some of the most meaningful work exists in moments, installations, or experiences that occur between architecture, art, fashion and performance. It’s a discipline that can stretch and morph, and that’s what makes it exciting.