Upon returning, the sky above home seemed both the same and unrecognizable: a pale, quiet blue, unable to restore the amplitude I had breathed elsewhere. In the Andes, space was a concave vault that pushed the gaze outward; here, everything appeared to draw back. From that distance I understood: I no longer saw as before.

There is a point at which travel ceases to be an itinerary and becomes a stance. For Gaia Anselmi Tamburini, that point takes the form of Cieli Sonori, curated by Sara Castiglioni: a project stemmed from the experience at Mater Iniciativa, in the heart of the Peruvian highlands, where nature, culture, and research are not declarations but daily practices. Between 3,500 and nearly 5,000 meters above sea level, photography shifted to a new breathing pace: less urgent, more contemplative. Casa Colibrí—a green refuge inhabited by dozens of hummingbird species—was the threshold; from there, each morning, the path led to Moray, the concentric terraces of the Inca, and Mater’s research center. Hours in the field with botanists, conversations in the van as thin clouds grazed the peaks, each breath made rarefied and therefore intentional: in this way the image learned to fall silent, to let a voice emerge.

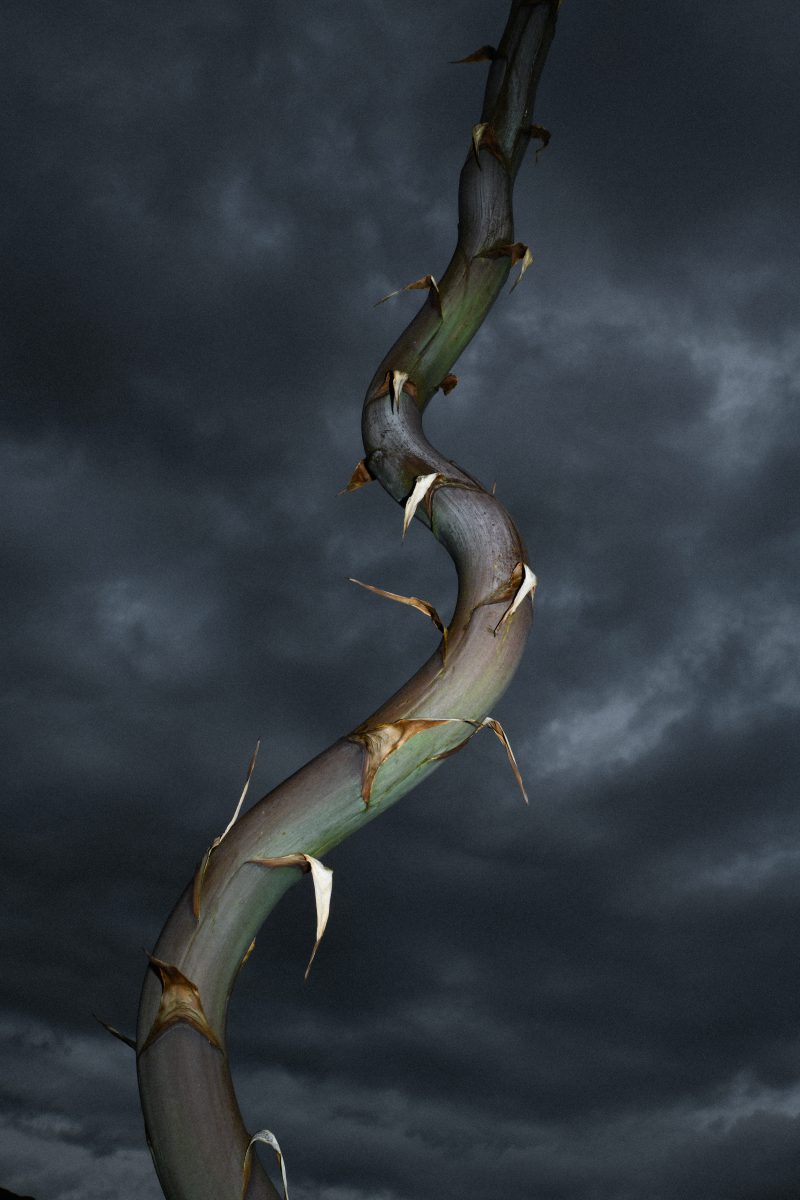

At first, an almost documentary impulse prevailed, an inclination to accumulate visions, places, encounters. Then came a fertile crisis, the kind that hollows and lightens: subtract, thin out, entrust oneself to the essential. The communities met along the way did the same each morning, pinning a flower to their hats according to the day’s emotion—a minimal, powerful lexicon. There the symbols took form: the flower as a sign of belonging, the root as a memory that persists. Not mere subjects, but words in a shared language. Gaia began to look closely, at a respectful distance, allowing gestures—rather than the idea of a gesture—to guide the shutter.

Sound entered almost by necessity. A small recorder, headphones like a perceptive antennas, and every detail—wind, footsteps, leaves, distant bells, breath—expanded to reveal layers the eye alone cannot embrace. Recording became a form of meditation; listening back, a way to re-enter the image and lend it depth. Nearly ten hours of audio traced a parallel geography: skies that resonate in the photographed subjects, horizons that vibrate, landscapes that expand beyond the edges of the print.

Hence the material and relational choices of the installation. The first collaboration is with composer Nicola Ratti, who welcomed and recomposed the field recordings with a sensitivity capable of preserving the original breath of the sites. In dialogue with architect Riccardo Orsini, curator of the exhibition display, the photographs are printed on aluminum plates which—thanks to small exciters—transform into resonant surfaces. The image is not only seen; it vibrates with sound, echoing the place it depicts, and invites a tactile way of listening.

For the opening at BiM, this score will unfold live: traditional wind instruments gathered during the residency—entrusted to the MMMM collective with Alberto Morelli, Andrea La Pietra, and Lorenzo Saini—intertwine with contemporary electronics, creating a dialogue between ancestral timbres and new sonic textures. Light also plays an essential role, with Max Milà Serra’s luminous installations inhabiting the space like a restless flock of ancestral creatures.

In the background remain the faces and names of those who offered another way of being in the world: the botanist Efrahim and his patient knowledge; the researchers who skip meals to witness a rare flowering; the encounters that, without fanfare, change the rhythm of a day. Within this network of relations, Cieli Sonori finds its voice: not a story about the landscape, but a dialogue with it, where images become listening, and listening becomes care.

And the sky? It returns again and again—not as a backdrop, but as the chord holding everything together. To look at it is to remember that seeing also means belonging: to an altitude, a rhythm, a community of gestures. Gaia Tamburini’s photographs do not seek to give the final word; they hold an echo, they open a space. They invite us to linger long enough to hear that every flower is a spoken thought, every root a pact with the earth, and that the image—when it finds its time—can, with radical simplicity, become an act of care.

Sara Castiglioni: What first drew you to Peru, and how did your connection with Mater Iniciativa begin? Was there a specific curiosity, experience, or intuition that sparked your desire to explore that context through photography?

Gaia Anselmi Tamburini: I first came across Mater in 2019, shortly after finishing university, as I was searching for places that reflected my values—contexts where nature, culture, and research could engage in authentic dialogue. Although their residency was only open to artists and I came from a product design background, I decided to write to them anyway.

Over the years, Mater remained a quiet point of reference. When my path in photography became clearer, I felt the need to return to that initial desire. I applied for the residency with little expectations, as they only select one resident per year. Exactly at a moment of discouragement and uncertainty, I received the answer: I would leave in two weeks to spend a month and a half in the Peruvian Andes.

Mater, for me, was not just a physical place, but a space full of visions, roots, and possibilities. I needed to slow down, to make space. To allow a personal research to emerge—one that combined image, listening, and thought. At first, it wasn’t easy to find the right rhythm, to truly listen to what that landscape had to say. Over time, I found a different pace. More essential, more clear. A way of working that was closer to what I had been looking for.

SC: The exhibition Cieli Sonori explores the intersection between sound, sky, and landscape as a space of memory and ecological awareness. First of all, how did the title Cieli Sonori originate? And how did this layered sensory approach shape your way of seeing and photographing the environment around you?

GAT: The only starting point I had at the beginning of this project was the idea of combining sound with images. Often, when looking at a photograph, I could hear sounds that brought me back to that moment, and I wanted to capture that connection in a duality that could work. I believe music has the power to amplify what we see every day—it intensifies emotions and makes sensory experiences even more vivid.

That’s where the title Cieli Sonori comes from: the sky, in constant transformation, was the first thing I noticed, and the sounds I recorded felt like skies resonating through the photographed subjects.

Following this instinct, I brought a field recorder with me. It was a new tool for me, and interestingly, having no prior experience meant I had no external influences—only my way of seeing and feeling that place. This approach guided me, just like when I first began taking photos as a child, driven by pure curiosity and without filters or expectations.

Recording sounds opened up a whole new dimension: I would take a photo and then, listening back to the audio, I could delve even deeper into the image. Wearing headphones and recording sounds became a sort of meditation, where every detail was amplified exponentially. In this way, I collected nearly ten hours of audio recordings…

SC: Your images feel like silent epiphanies, almost meditative in their stillness. What role do slowness and listening play in your creative process, especially in a context of biodiversity and cultural interconnection?

GAT: During the first two weeks of the residency, I began photographing the way I was used to on set, following my usual method. I traveled, visited places, met different people and communities—all of whom touched me in different ways—and I tried to capture everything, to bring home as much material as possible. But it was turning into a somewhat scattered reportage, lacking a strong central thread. It was an objective account of what I was experiencing, but something was missing.

Then I went through a crisis, a deep reckoning that lasted most of the residency. I had to let go of some certainties about how I worked, allowing myself to be moved by new, much simpler truths. In such an essential place, where people dedicate themselves to taking care of the land, the animals, and their small communities, it felt almost instinctive to return to simplicity in my work as well.

It was a process of stripping away everything unnecessary and making space for what, in that moment, was most essential and fundamental—just like the people around me did in their everyday lives.

SC: At the heart of this project are elements like the flower and the root, symbols of connection and fragile equilibrium. How do they speak to your personal understanding of belonging, and how do you translate such intangible ideas into visual form?

GAT: This question brings me back to the first photo series I created as an adult: it was a bouquet of flowers. It may seem simple, but that bouquet, a gift from someone special, I observed and photographed from every angle. It reawakened something in me and made me realize I wanted to deepen my relationship with photography. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that everything started there.

Finding myself in the Andes, at 3,500 meters above sea level, immersed in such generous, omnipresent nature, was a return to that initial feeling I’d had years before. But I didn’t get to it right away—it was a gradual process. At first, I observed from the outside, then I truly began to listen. The people I lived with decorated their hats every day with different flowers, chosen based on the emotion they were feeling. For them, these weren’t just ornaments, but powerful, almost ritualistic symbols.

Through those daily gestures, I started to see flowers differently—not just as visual subjects, but as part of a language. I began photographing them more attentively, from a closer perspective. In that simplicity, I found a tangible way to tell stories about belonging, relationship, and care.

SC: The exhibition will feature photographs printed on aluminum sheets, each transformed into a sounding surface reproducing fragments of your field recordings. What led you to intertwine image and sound in this way?

GAT: The idea of using aluminum sheets came from a conversation with my friend Riccardo Orsini, an architect with whom I developed the entire exhibition setup. From the beginning, one of the most important aspects of this project for me was sharing the process with people I admire and feel a natural connection with. I didn’t want the project to become self-referential—I wanted it to be a shared journey capable of generating real exchange.

Riccardo was one of the first people I talked to about it, and we immediately clicked—especially when we identified the core idea: the images had to vibrate and reproduce the sounds I had recorded in the field.

From there, the idea emerged to use aluminum plates as resonant surfaces. Each photograph is printed on a sheet that, thanks to an exciter—a small device that transforms the surface into a speaker—vibrates and emits sound. It was a fundamental step for the exhibition.

SC: On a more practical level, how did your residency with Mater Iniciativa take shape day by day, especially considering the physical and environmental challenges of working at nearly 5,000 meters in the Andes?

GAT: I lived in a small lodge called Casa Colibrí, a true green haven at 3,500 meters above sea level, home to around 30 different species of hummingbirds. Everything was very modest, but nature held the greatest treasure. Every morning I woke up at 6 a.m. to take a van that brought me to 4,200 meters—to the headquarters of Mater Iniciativa, a research center near Moray, an ancient Inca agricultural consisting in large circular terraces dug into the ground, considered a kind of experimental agricultural laboratory.

We had breakfast with the research team at 7, then everyone went about their work. Often, we skipped lunch to go on field expeditions, exploring and studying the surrounding nature, stopping for a snack around 5 before returning to our homes.

During these days, I often worked alongside a botanist named Efrahim, a local man trained in traditional knowledge who was researching rare high-altitude Andean species—one of the most wonderful people I’ve met. Every morning, while riding in the van, I felt like I was dreaming—watching the low clouds and surreal landscapes constantly changing.

Being in that place, alone, yet surrounded by people with different but inspiring endeavors, was fundamental: in the end, you were there with your own project, and your questions…

SC: Part of the project includes a musical collaboration with composer Nicola Ratti, who reinterpreted your on-site field recordings. How did this exchange unfold, and what did it mean for you to hear those landscapes transformed through his compositional language?

GAT: I was looking for someone who could interpret my sounds with sensitivity—someone who could understand the relationship with the surfaces and the space that would host the installations. I already knew Nicola Ratti’s work and immediately felt he was the right person for this part of the project. I reached out to him while I was still in Peru, and he responded with enthusiasm.

I won’t hide that, when he sent me the first draft of the composition using all my field recordings, I was moved…

SC: During the exhibition inauguration— on 29th October at BiM, Milan—there will be a special live performance by MMMM collective. The show will incorporate traditional wind instruments collected locally during your residency. How did this idea come about, and what inspired the collaboration?

GAT: During my time in Peru, in addition to field recordings, I became curious about traditional local instruments. I met some artisans who made them, and from there, a whole new world opened up. I instinctively decided to bring some instruments back to Italy, with the idea of entrusting them to someone who could interpret them respectfully and sensitively—someone able to understand their spirit, not just their form.

Talking with Andrea La Pietra, we immediately thought of Alberto Morelli, an ethnomusicologist who has studied traditional instruments and musical practices his entire life. Alberto enthusiastically embraced the idea and began working on a composition based directly on the sounds I had collected in the Andes. He will be joined by Lorenzo Saini and Andrea, who will enrich the live performance with an electronic component, creating a dialogue between ancestral sounds and a more experimental, contemporary sensibility.

This fusion reflects the core of the project: integrating traditional Andean instruments—rich with cultural meaning—into a contemporary composition that reinterprets them through electronics. This immersive concert will be a kind of performative play, in which these small instruments, gathered during the residency, will be played live to weave together ancient roots and modern languages.