Campeggi has been making design history since the late 1950s, constantly transforming and weaving ongoing relationships with the designers who have helped to make its name. But what does it mean to produce transformable objects? Guglielmo Campeggi, grandson of the founder, and Lorenzo Damiani, designer slash inventor and—almost—a member of the family, talk us through it. It is a laidback conversation that, much like the DNA of the Brianza-based company, changes and takes different directions as it dissects the ecosystem that revolves around the birth of a product, regardless of function. Because in the end, there’s always an excuse to design.

Claudio Campeggi’s favourite sport was hunting for designers. Son of Luigi, the upholsterer from Brianza who founded Campeggi in 1958, Claudio had an unerring flair for finding designers who would contribute their creativity to the family business.

Some will probably remember seeing him on Sunday afternoons at the Salone Satellite during Salone del Mobile international fair in Milan, where he used to cultivate fruitful dialogues with creatives. He spent just as much time forging links with the stars of the contemporary art scene: Aldo Mondino and Antonio Paradiso were all friends of his. Until he passed away in 2020, he was a visionary director, accompanied by his brother Marco, his right-hand man, who was in charge of the production and administration. Then came his son Guglielmo, an architect by training, who joined his uncle Marco, his cousin Nicolò and his brother Giacomo at the company where, to this day, they continue to experiment with transformability through material, spatial and technological research, infused with historical and cultural references. All this, without ever taking it too seriously. Guglielmo Campeggi and Lorenzo Damiani, a longstanding collaborator who has worked with Campeggi since the early 2000s, tell us all this in a two-part interview.

Passionate about architecture, Guglielmo Campeggi is an enthusiastic character with a great desire to get things done and give voice to the brilliant ideas of designers. He is fascinated by the dualism intrinsic to the transformability of Campeggi’s products, a path he explores in order to propose solutions that change our perception of space itself.

Lorenzo Damiani is a keen observer. If you ever meet him, he may well bring a backpack full of light bulbs, taps, handles, felt pads, glasses and other prototypes as a pretext to explain his way of seeing the world because, after all, we are what we make. He finds it a good way to show who he is. Before sending them for production, he likes to have his objects delivered to the studio so he can spend a few days with them. On some occasions, this habit has allowed him to make important changes and find new solutions.

Giovanna Castelli: Campeggi is a leading brand in transformable furniture. What is the standard definition of transformability?

Guglielmo Campeggi: It is a type of design that not only improves the living space of an environment by increasing options for movement and use but also allows us to experiment with new and continuous spatial configurations, adapting to the needs of our time. One example is the sofa bed, a classic Campeggi product: in the not-too-distant past, you would find them in secondary residences by the sea, placed there out of need and not often used. Today, it has become the bed sofa and taken on a fundamental role: we use it daily because our living space has shrunk. In a studio apartment, the sofa bed takes centre stage with its dual function: it makes the room both living room and bedroom. Transforming a space means changing one’s daily habits.

Lorenzo Damiani: Transformability allows multiple functions in one object and consequently saves space. With Campeggi I have very often ‘incorporated’ existing objects into my creations, such as the bicycle stand in the case of Underdog.

GC: What about a less official, more laidback way of defining it?

GC: Design should not be taken too seriously. Much like life. This is a characteristic that makes Campeggi unique: transformation in relation to play and fun. This positive and joyful mood was developed over the years under my father’s artistic direction. When you play, it’s like moving something and when you move something, it’s like playing. That’s the way he saw it. Transformability is the fil rouge for Campeggi. And then, of course, the designers contribute their own identity. The identity of the company and the designer come together to create uniformity in the collection. With Vico Magistretti, we worked on ready-mades of existing objects; with Damiani, objects become technical and innovative. With Emanuele Magini, they are more plastic, sculptural, and almost pop; Sakura Adachi, on the other hand, has a cabinetmaker’s background; and Matali Crasset’s high-tech shaped pieces from the early 2000s are immediately recognisable as the French designer’s work.

GC: An object is always born into a context, historical or mental, from which it derives its functionality, symbolism, materials and even technology. How do you define the context of a designer?

LD: Research is the mental gymnastics needed for intercepting an idea to which you can cling design-wise. What interests me is researching a small percentage of novelty to justify a new project. Perhaps the functional aspect, the materials, new processes, or even the message that the design itself conveys. In a world already saturated with ‘things’, it is essential to find a reason, even a tiny one, to justify the presence of a new object in the world. It is important to look around with curiosity. It becomes useful to observe how a person sits at a school desk or how they eat while sitting on a wall, or to understand that chipboard can be refined and marble can be bent. I believe that my reference context is anything that can activate these thoughts into pursuing a project that will meet a new need, suggest new behaviour or imagine new solutions for the use of materials. That should always be the intention, it is not always successful but it is important to try. The beauty of our work is that in the end, there’s always an excuse to design.

GC: How has the company changed over the years?

GC: My grandfather was among the first who conceived the sofa bed as a multifunctional piece of furniture. Architects Alberto Salvati and Ambrogio Tresoldi designed a table bed and a wardrobe bed for us, which were presented in 1972 at The New Domestic Landscape exhibition curated by Emilio Ambasz at MoMA, today remembered as a cult event in the history of design. The company has always produced in response to society’s ever-changing spatial needs and these needs have been met over the years with different projects: from the more traditional to the more radical. The result of constant research into the role and function of the domestic object, which should not be understood as something static, but interactive and dynamic like our lives. And, above all, useful.

GC: Brianza is the design Mecca of yesterday, certainly, but also of today and tomorrow. How does it feel to run a company at the centre of all this?

GC: Giulio Manzoni, a designer who has worked with us for more than 30 years now, is our technicality expert, the last romantic of design control. He once said that Brianza was like a great big DIY store. When you needed to prototype an object, all you had to do was go to Brianza and you would find everything you needed at your fingertips. There was so much scope for experimentation and construction—everything was accessible. Supply was so high at the time. When Manzoni told me this, I envisioned Brianza like a strip in Los Angeles: a motorway with a multitude of companies and craftsmen’s workshops on either side. So many companies here developed thanks to the intuition of enterprising craftsmen, carpenters and upholsterers, just like my grandfather. And like Campeggi, I too feel as though I’m in constant transformation.

Speaking of artisans, Lorenzo has a very fluid way of working, entering into an agile dialogue between design and craftsmanship…

LD: I design both handcrafted and industrial objects. I think it is a question of attitude. The context, whether craft or industrial, becomes a nuance. The way I approach design is the same but with a handcrafted product, I feel more freedom to dare, perhaps even make mistakes. They are two different responsibilities, but both are stimulating.

GC: How did you start working together?

LD: Those were the years that I took part in Opos and Salone Satellite, I think it was 2000. One day my phone rang. It was Claudio Campeggi asking to see me in Anzano del Parco in his very direct and pragmatic way. He had got my name from Beppe Finessi. The call must have lasted no more than two minutes and at the next Salone del Mobile, we presented an object that contained both a sofa and a table within its soft structure. For me, seeing ‘UnoperPiu’ in dialogue with designs by Vico Magistretti, Denis Santachiara and Giovanni Levanti was an incredible opportunity. Thank you, Mr. Claudio… That’s what I’ve called him for the past 20-odd years.

GC: Rest seems to be a recurring Campeggi theme. What is your relationship with rest, sleep, dreams and the subconscious?

GC: We are a company that produces products intended for sleep. Sleep is a consequence of being awake. Good rest is essential for an active and functional day, it is not yet a leitmotif of ours but perhaps it will be after this interview!

GC: What does Campeggi aspire to now?

GC: Maintaining continuity and enjoyment, which have always characterised the company. Making the obligatory transformations happen but at the same time remembering to develop the products in line with the unique method of transformability that has distinguished the company since its inception.

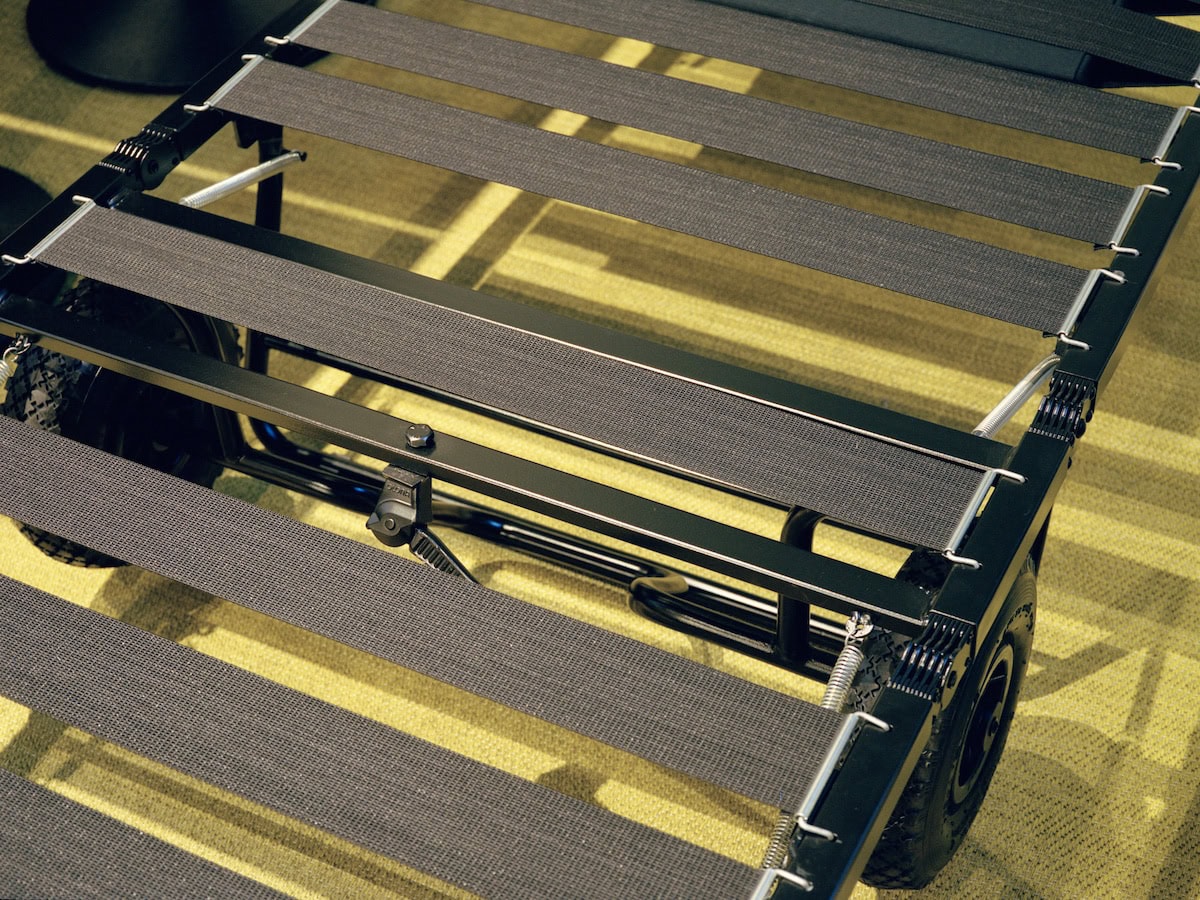

Underdog behind the curtains, by Lorenzo Damiani

“The so-called ‘makeshift bed’ can be seen as an underdog object yet, in moments of need, it solves a pressing issue. When we have an unexpected guest, Underdog comes to the rescue. Years ago, I was reflecting on the needs of people living in unstable situations, often without a fixed abode. This later morphed into the Campeggi product, which retains the soul of the initial idea. It is a versatile object: a comfortable but ‘more or less makeshift’ bed that can be used as a sofa when needed, to be displayed without preclusions. An armchair with a bare aesthetic, devoid of superfluous frills, which can be ‘parked’ anywhere within the space. The presence of two big wheels and the trestle makes it clear—right from the start—that it is not afraid of movement. The kickstand is a ‘romantic’ touch that takes me back to times long past when I used to clip cards to the spokes of my bike to simulate the rumble of a motorbike. Today, when I lift it and hear the sound of the spring, my mind instantly goes back to riding around with friends. Even the sound aspects generated by an object and their references can be important.”

If Underdog were a song…

“Negrita’s Qui non è Hollywood might be the right soundtrack: “Everything is too much and what you have is enough / maybe one day you’ll understand”. Crazy Andy was right! That’s a great phrase to describe designing a simple object that will make a friend happy by giving them a good night’s sleep.”

The genesis of a Lorenzo Damiani x Campeggi product, by Guglielmo Campeggi

“While working on Underdog project, Lorenzo and I have established a kind of tradition: we used to meet with my uncle Marco at the company early on Saturday mornings to work on the product from 7:30 a.m. to midday. It’s like a continuous workshop, we make many spontaneous changes to the prototype there on the spot. There is no specific time frame, rather intensity and clarity are what count. We occasionally run into difficulties: a chair on paper might work in practice too, but a chair that transforms is an action that we have to make happen so the discourse shifts to engineering and the mechanical. These are special moments during which original ideas take shape, like Underdog, a product that became ready-made and to which wheels were added. A mobile object that keeps changing.”