Questions On is the video interview format created by C41. It consists of three simple questions addressed to our network of friends, partners and creative minds. This series will go through Printed Narratives, questioning the role of contemporary publishing in the digital era. This episode features Federico Clavarino on the occasion of his participation in Charta Festival, that took place from the 17th to the 25th of July 2021 in Rome.

Charta is a festival of contemporary photography that aims to highlight photographic books and independent publishing. The theme of this edition, Demons, aims to investigate all the darkest derivations of the human condition, from territorial to social or psychological problems, giving a transversal point of view on the criticalities of the contemporary world.

Federico Clavarino after obtaining a Master in Literature and Creative Writing at the Holden School in Turin, 2007 he moved to Madrid where he has been teaching photography at BlankPaper School since 2011. In 2011 he presents his first book Ukraina Passport (Fiesta Ediciones), obtaining an honorable mention as best photography book of the year at PhotoEspaña. In 2014 he publishes together with the publishing house Akina Books his second project, Italy or Italy, whose original prints are exhibited in 2015 at FOTOGRAFIA – International Festival of Rome, and wins the sponsorship of La Caixa Foundation FotoPres with which he starts working on a new project, Hereafter, published in 2019 by Skinnerboox. Two more of his works are published in book format: The Castle (Dalpine, 2016) and The Vertigo (Witty Kiwi, 2017). The Castle is exhibited at PhotoEspaña in 2016 and at Rencontres D’Arles in 2017. Since 2016 he has been represented by the Viasaterna gallery, which in 2019 is exhibiting Eel Soup, a project developed together with Tami Izko. Also since 2016, he starts conducting workshops frequently, collaborating with academies (ISSP, ISIA, PICA), museums (CCCB, MACRO, Museo San Telmo, Arnolfini Centre), and universities (Universidad de Navarra, University of South Wales, Leeds College of Art, University of Roehampton). In 2020 he obtains a Master of Research from the Royal College of Art in London.

After studying Film in Buenos Aires and then Journalism in Madrid, in 2017 Tami Izko was introduced to the world of pottery while living in Lisbon and learned the practice from local artisans. Using the plasticity of clay, she focuses on the epidermal nature of this material that she then shapes into organic forms working as a reflection and abstraction of the self and the elements that configure it. In the context of this research, Tami Izko began collaborating with photographer Federico Clavarino in 2018 developing the series Eel Soup, in which sculptures and images negotiate in a dialogue revolving around intimacy, and the physicality and intersections of coexistence. She currently lives between London and Milan, where she’s continuing with her research around ceramics while working on a series of writing projects. One of the series she developed during lockdown earlier this year – Twofold – was featured in a joint publication between the Royal College of Art and the Design Museum. Tami Izko most recent work, Wounds, revolves around connections between memory, trauma, and resilience and was featured in Artissima Unplugged 2020. Bezoar, an exploration through clay that focuses mainly on our responsibility towards the extraordinary and the mechanisms behind magical thinking, is a work in progress she’s currently devoting most of my time to.

About Ghost Stories – words by Federico Clavarino:

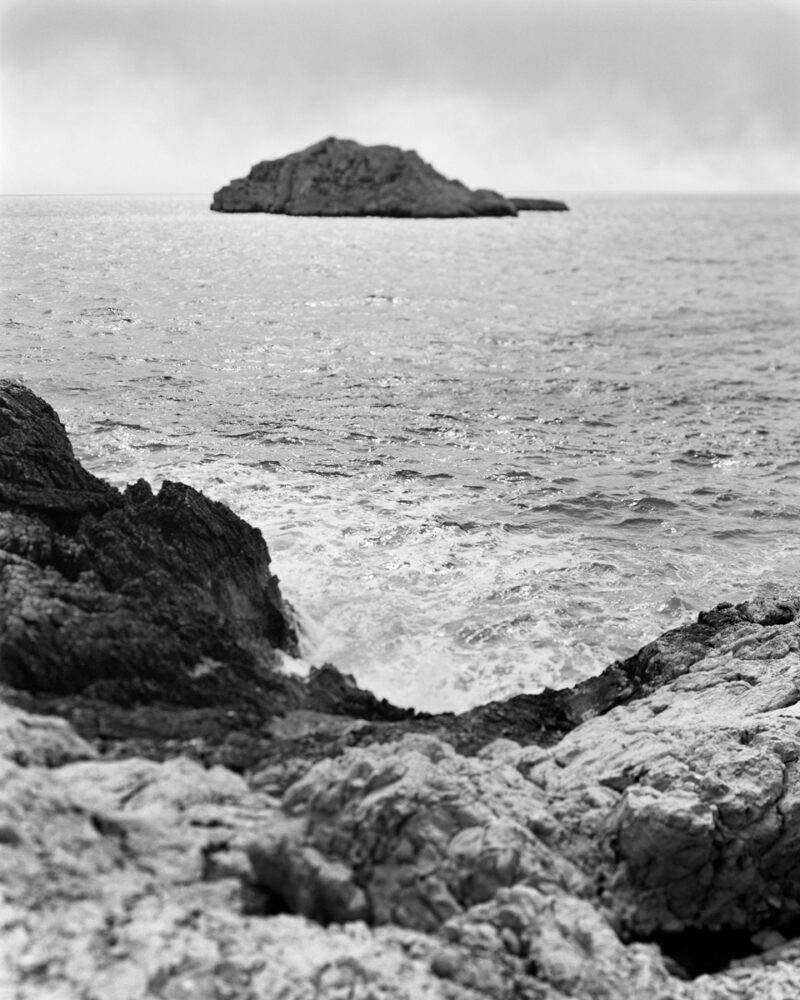

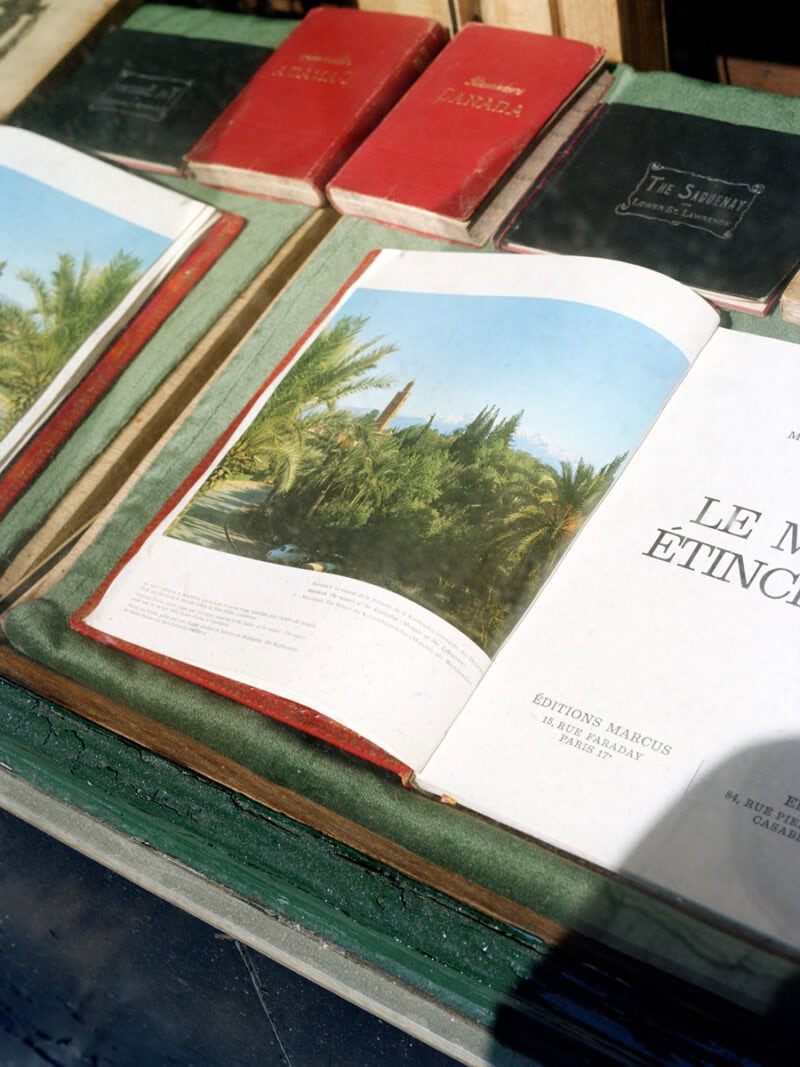

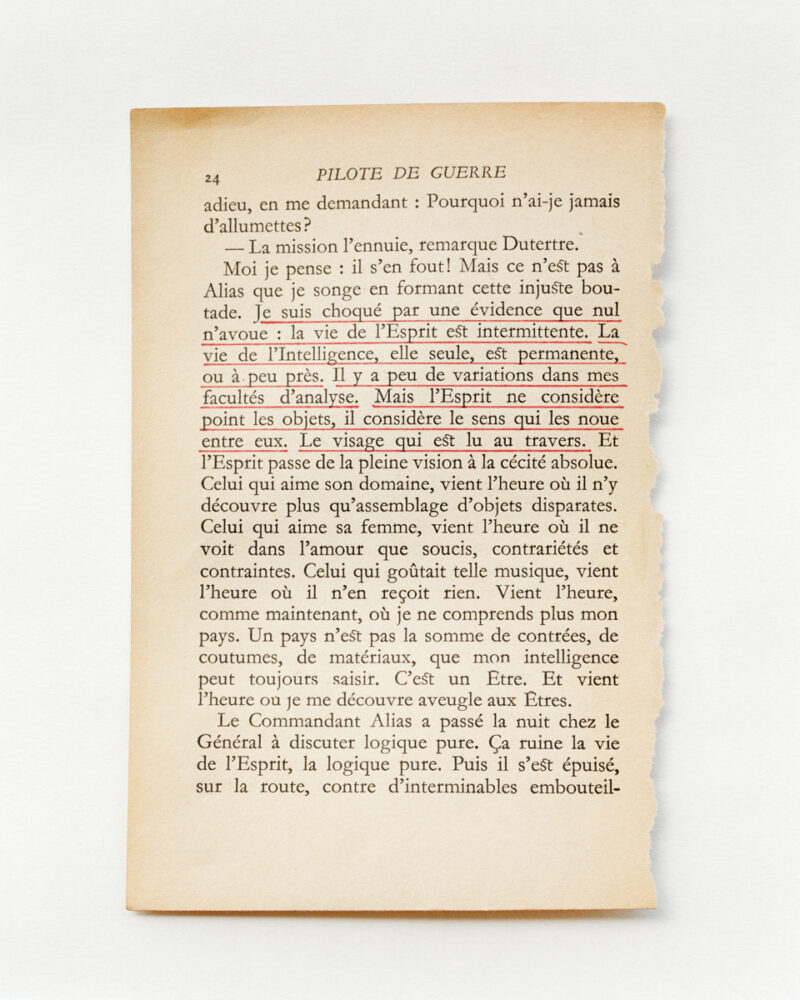

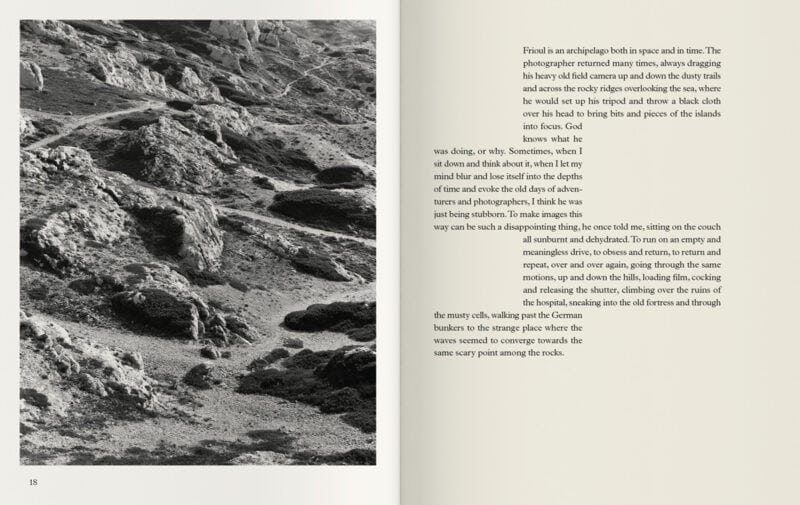

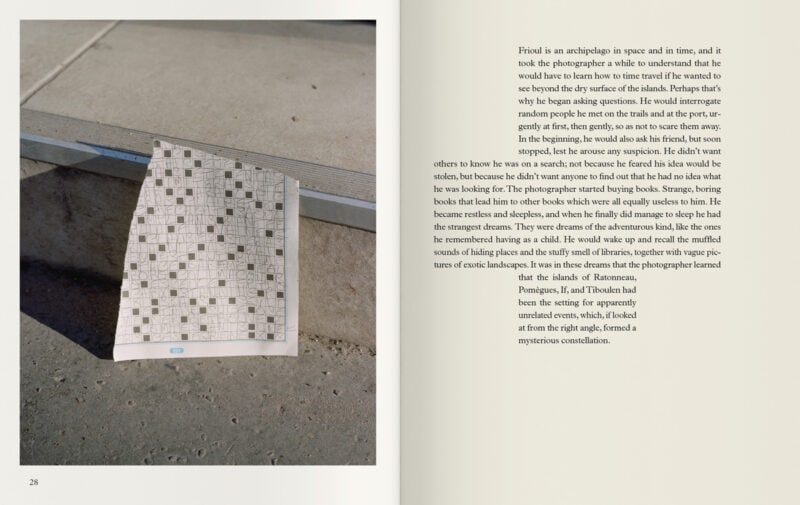

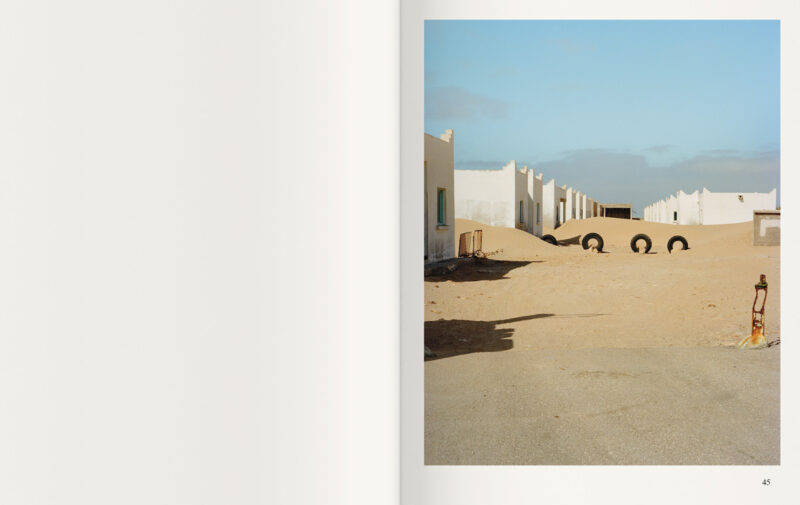

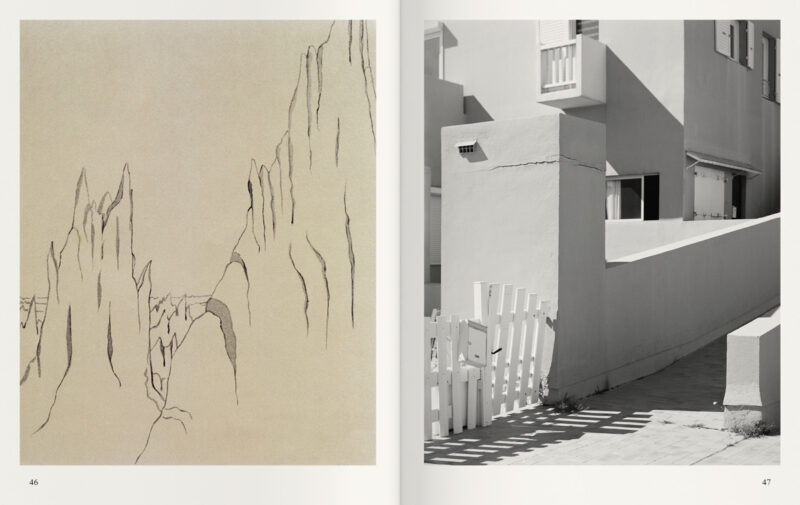

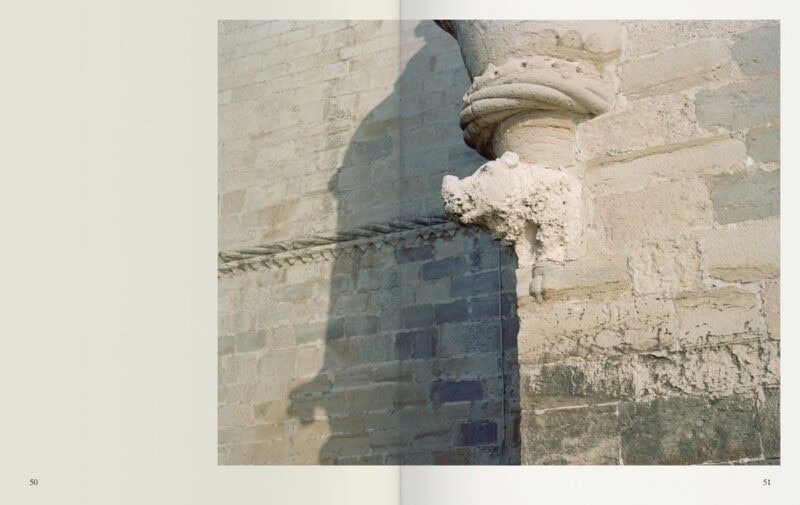

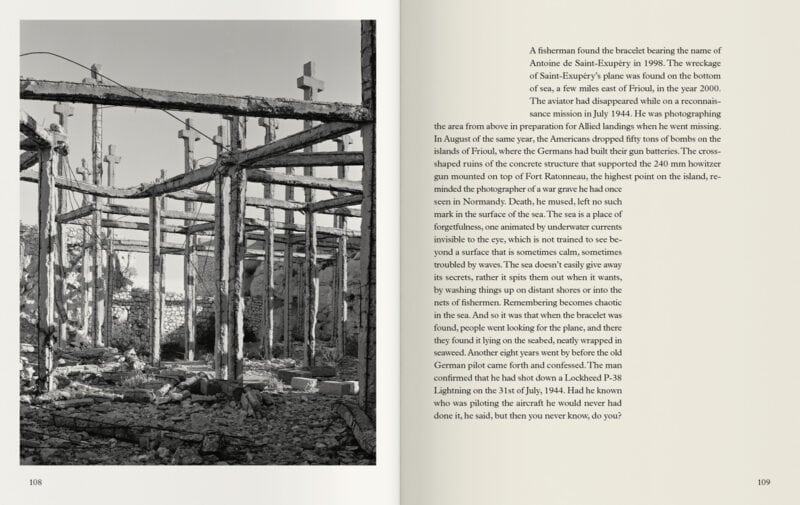

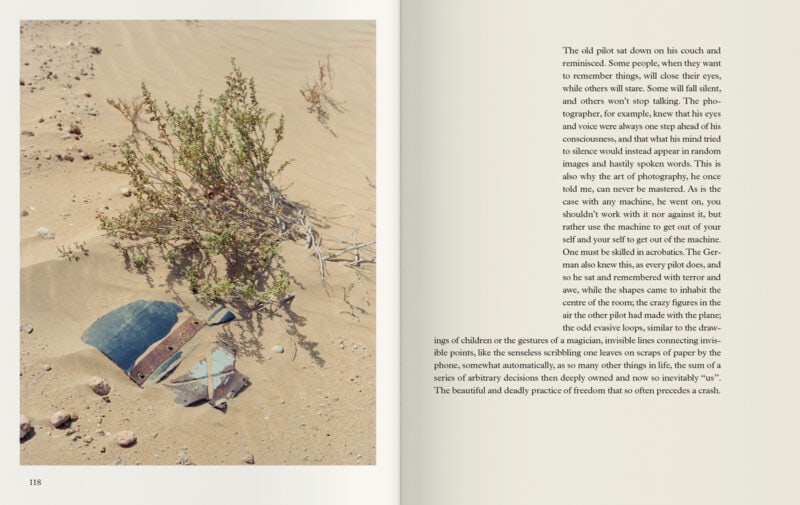

The Frioul archipelago is located in front of the gulf of Marseille, and it comprises four islands: Ratonneau, Pomègues, If and Tiboulen. Frioul is an archipelago in space and in time: these islands have been the scenario of apparently unrelated events that make up a mysterious constellation. In 1516 king Francois I ordered a fortress to be built on the island of If, which was then used as a prison in the XVII century. Its most famous inmate was Edmond Dantès, the protagonist of Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Montecristo. Inside one of its cells, it is still possible to see a hole Dantès made in a wall in an attempt to escape. On the 24th of January, 1516, the first rhinoceros to be ever seen in Europe was unloaded on Ratonneau. The animal was being shipped to Pope Leon X, and Francois I, king of France, hurried there to admire the beast. On its way to Rome, the ship ran into a violent storm and sank. Albrecht Dürer later made a woodcut of it from a sketch that was sent to him. On the 31st of July, 1944, Luftwaffe pilot Horst Rippert shot down a P-38 Lightning, which fell into the waters of the archipelago together with its unfortunate pilot, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. A bracelet bearing his name was found by a fisherman in his net while fishing near Pomegues decades later. Ghost Stories is a series of photographs that is meant to weave together all of these events, occurred in the same space but at different times.

Why Ghost Stories?

The title comes directly from the stories I’ve found, which all have to do with people, characters and animals who disappeared at some given moment in the Mediterranean waters, near these islands in the Frioul archipelago, and who somehow came back, so they led this second ghostly existence. There is this English word that is “the haunt” (which would mean to haunt). The persistence in the present of something from the past that is uncomfortable, that doesn’t go away, so that’s the reference to the ghost. Either to specific stories, such as the story of the rhinoceros that disappeared after being brought from India following a shipwreck, which then became the model for hundreds of years of erroneous, or at times fanciful, depictions of rhinos within European art history. In another case it is the story of the Count of Montecristo, then a story of fiction, a fantasy story. He too, pretending to be dead, is thrown into the waters near the Frioul and then leads this second life as the Count of Montecristo, carrying out his revenge in Paris. The other references within the book, in a more contemporary and more transversal way, also lead you to reflect on how certain other events and certain other stories in the Mediterranean have their consequence, and their life in the present, their fantasy life. It is a bit of an invitation to reflect on the fact that the past does not end, but constantly returns.

What do all these unrelated literary events give to the place? Is there something archaeological in your approach to photography?

The other big theme of the book – if the first is time travel or the idea that in this place, which I live in the present as a photographer, these stories from the past come back and are found – on the other hand, there is this idea that in the middle of rocks in the Mediterranean, where basically there seems to be no trace of those stories, one can derive other spaces. So to tell the story of a place, you can’t stay in that place, you have to go somewhere else. They are all connected in some way. And not connected in the way we understand it today, that is, with the fact that we live in a more global culture, in which some people can move with more agility and others with more effort, but what is missing is the fact that the moment you look at a place and what happened in that place, you have to, almost immediately and compulsorily, go somewhere else; a place takes you to other places, a place contains other places, a story contains other stories… So there are not really materials there that refer to the story of the rhinoceros, for example. On the Frioul Islands, there are rocks, there are perhaps remains of other buildings, which have other stories. But there is that story, that links that place with the British Museum, maybe with a museum in a small village in France, with the national library in Belgium and with a porcelain museum in Dresden, for example… But also with a small village in the south of Morocco and in the streets of Paris. It’s almost like saying: it’s impossible to be in a place, to live in a place, because even the emptiest of all places – such as windswept islands in the middle of the sea – without it connecting you to other places and other times.

Publishing could be seen as an anachronistic practice. Why do you think it could still have a role in shaping contemporary visual culture? Is printing a way to return images to where they belong?

Anachronism is part of my practice and interests, as the first question shows. I don’t believe in a torrent of history that takes you from one place to another, I think it’s much more complex, much more about coming and going. I lived through a moment in which, for example, the production of photography books underwent a change and a very interesting, strong push, starting with the evolution of new digital technologies, and online distribution, right? Many of us, photographers and artists, started to self-publish books or publish them with extremely independent publishing houses. We took advantage of the fact that it was possible to distribute and advertise our work online, it was possible to sell it online, and it was possible to sell it through digital printing techniques and to access, for example, smaller editions. Before maybe you needed to publish a lot of books before you had access to a certain kind of professional printing. So this has all changed, an old object has come back to life with more force than the years when new technologies were changing the landscape of book distribution and consumption. It’s also true that the way photography flows, for example, nowadays is mainly online and mainly through screens, that’s something I find is part of what we all do. When you print a photo, you share the image on Instagram for example. They are now hybrid chains of images, products and works and I find that they are not alternatives. The space that one opens can never, I think, be opened on a screen, precisely because of the physicality of the medium, because of its characteristics, because of how it is sent, because of the type of temporality that it opens up. Exactly as the work can never be experienced inside the book, as it happens inside an exhibition in a social place, it is completely different, it is a different relationship with your body. The same thing happens with the speed and possibilities that other technologies give you, such as experiencing images on a screen at enormous distances and extremely short times. They are really different tools, I don’t think one leads to the death of the other, on the contrary, I think they can enhance each other in interesting and unpredictable ways.