Questions On is the video interview format created by C41. It consists of three simple questions addressed to our network of friends, partners and creative minds. This series will go through Printed Narratives, questioning the role of contemporary publishing in the digital era. This episode features Antone Dolezal and Lara Shipley on the occasion of their participation in Charta Festival, which will take place from the 17th to the 25th of July 2021 in Rome.

Charta is a festival of contemporary photography that aims to highlight photographic books and independent publishing. The theme of this edition, Demons, aims to investigate all the darkest derivations of the human condition, from territorial to social or psychological problems, giving a transversal point of view on the criticalities of the contemporary world.

Antone Dolezal is a visual artist and author whose body of work surveys the cultural and political dynamics of American folklore and mythology. His work has been exhibited widely and is held in notable collections including the Museum of Contemporary Photography, New Mexico Museum of Art, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. His photographs have featured in media such as GEO, National Public Radio, Oxford American and Smithsonian Magazine, and he is the recipient of numerous visual arts awards. Antone has lectured at academic and non-profit institutions throughout the United States and currently teaches at the University of Nevada, Reno.

Lara Shipley is an Assistant Professor of photography at Michigan State University. Her photographic practice covers rural culture, identity, mythology, storytelling and photography’s relationship to evidence. She has had major gallery exhibitions across the United States, South America and Europe and her work is held in collections such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago and Nelson Atkins Museum for Art in Kansas City. www.larashipley.com

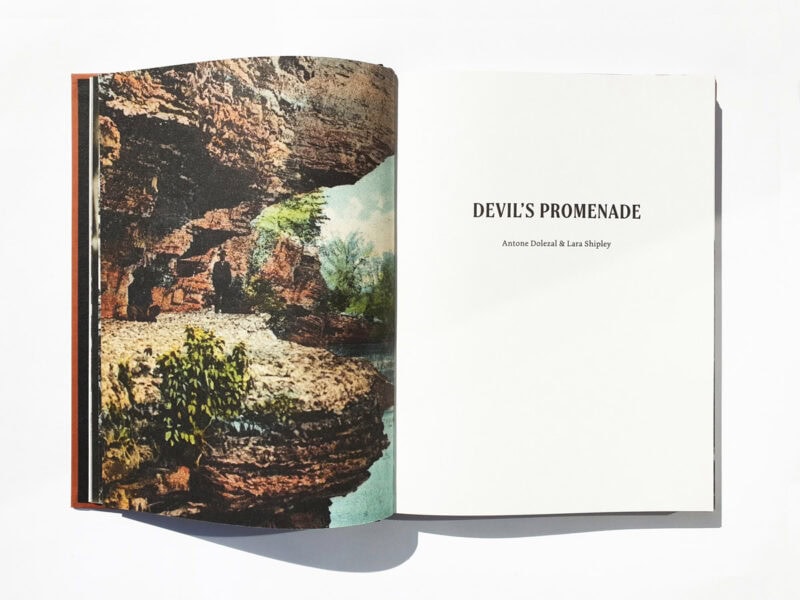

About Devil’s Promenade – words by Antone Dolezal and Lara Shipley:

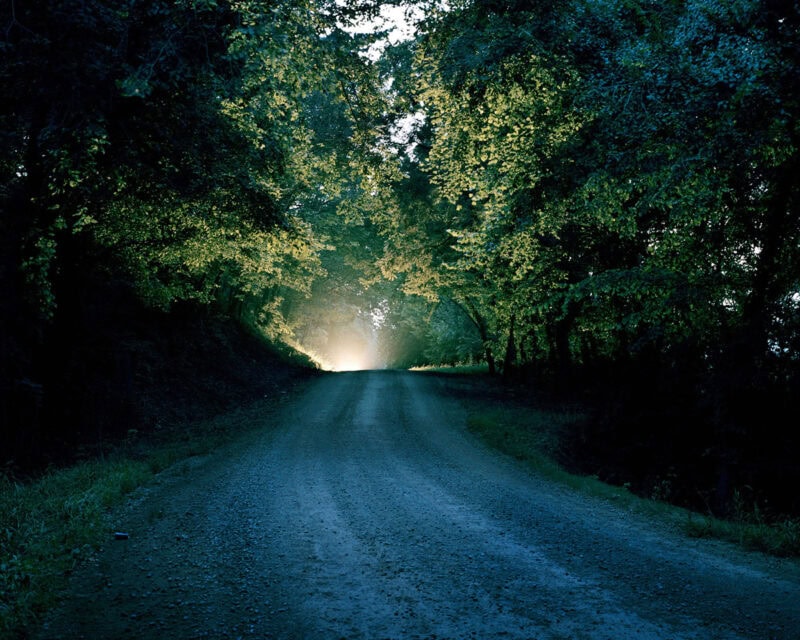

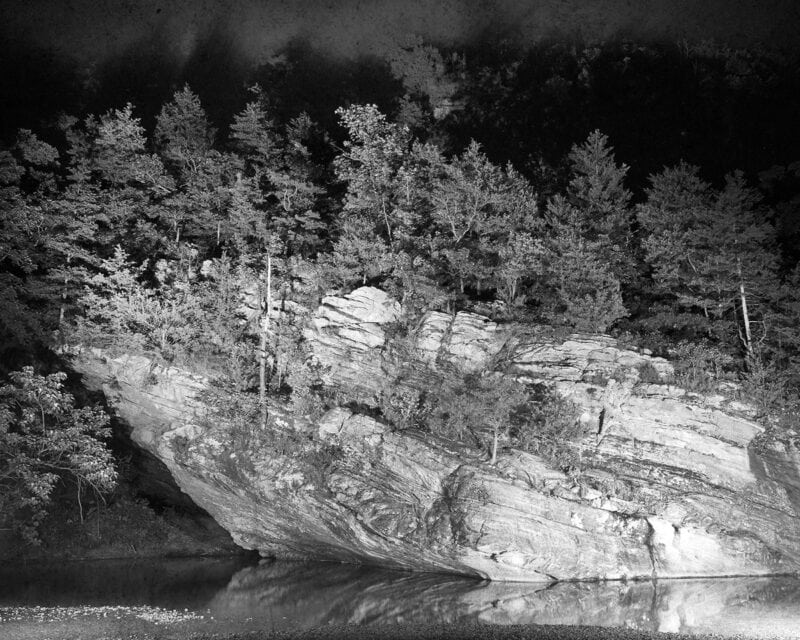

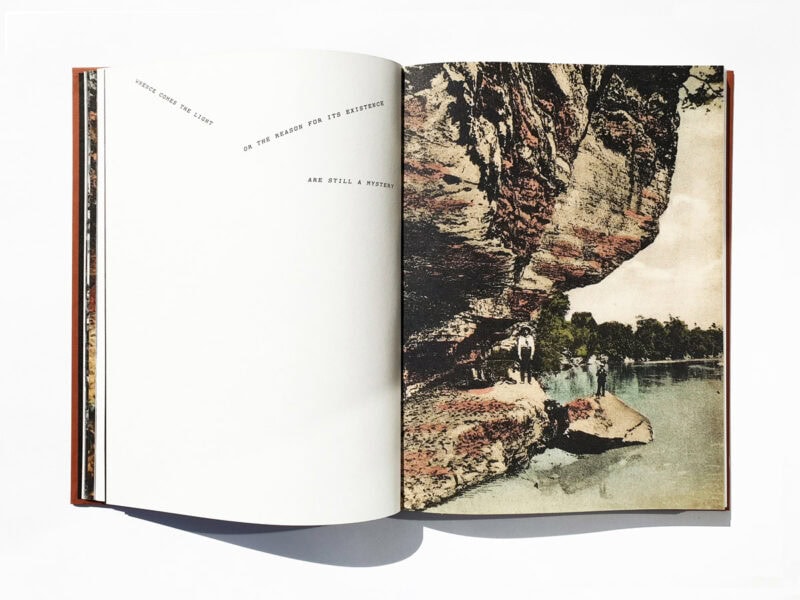

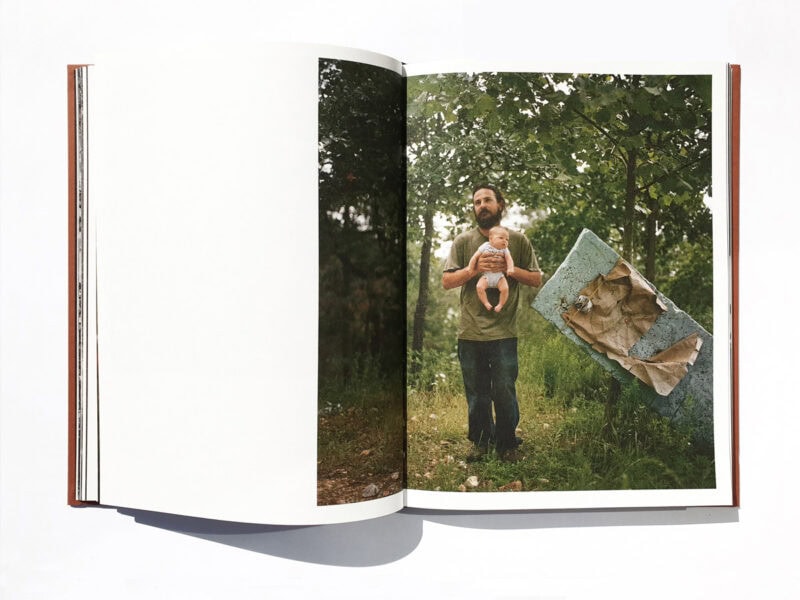

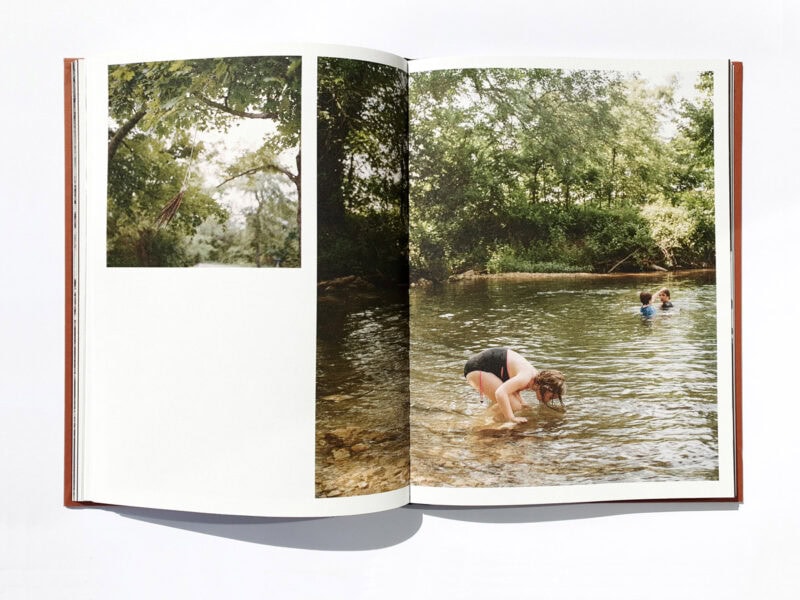

Dolezal and Shipley return to their home region of the Ozarks in the American Midwest, where locals persist in their search for a legendary floating orb of light that can only be seen from the Devil’s Promenade. It’s a lushly wooded road in an area where wanderers flock to seek possible redemption, or just to escape the boredom and darkness of ordinary rural life. This story-led book offers a nuanced, mysterious and tender representation by photographers returning to the place where they grew up, but also reveals the current, stark realities of a remote place in America.

Longtime collaborators, Antone and Lara currently live at nearly opposite ends of the United States but their point for making this work meets in the middle, at the physiographic intersection of four heartland states. Together they have documented Ozark people and landscape over a period of almost 10 years, drawn first by a desire to reconnect with their past, then compelled to relate something

of the character and rituals of an area where locals can become skittish around strangers. Their photographic interests encompass culture, identity, folklore and mythology of place—but forming a clear picture of this isolated place is complicated.

«Ozarkers always have been somewhat dualistic, believing that two great forces – one good and one evil – battle for control in each person.» (Stanley Burgess)

The roots of Ozark folklore were formed by 19th century pioneer settlers from Scotland, Ireland, Britain and Germany. From early on they had a penchant for sharing jokes and colorfully embellished stories within their community, passing down superstitions and lore to younger generations. Meanwhile, religion is central to social life in the Ozarks, having strongly shaped the area over more than two centuries. Locals are generally proud of their rural values and individualistic, traditional approach to life.

With Devil’s Promenade, the photographers take us along their journey into the thick woods where anything might happen; you may either bathe in the light of salvation, or come face-to-face with the Devil on a bridge, in the inky dark.

Why Devil’s Promenade?

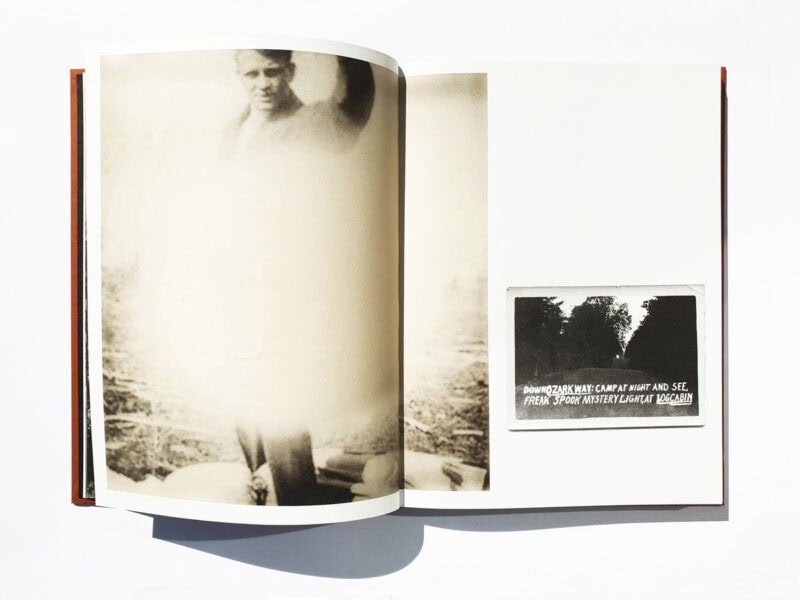

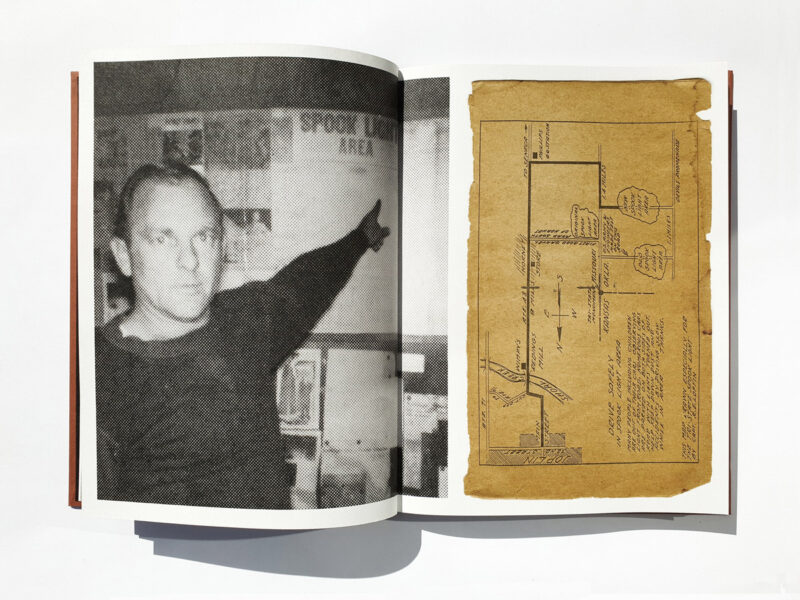

AD: Well, Lara and I begin this project about ten years ago and the Ozark is the region we are both from and we wanted to make a project about the place we grew up in, but also about the place that we left as adults and come back to. We really want to reevaluate what our relationship with the Ozark region was. So we decided to start talking about it and start focusing on the folklore traditions of the Ozark region. Those traditions were something that was embedded in our family history and our families were both really large – big storytelling families. We decided to focus on the Devil’s Promenade, which is a remote region in the Ozarks and it’s referred to by locals as a place they go out to and see what‘s known as the Ozark light, which is this floating orb of light that changes colours and it’s been a mystery for a long time of what exactly the origin of the light is. It’s also a place that locals claim to see where the devil lives. And so we thought that the duality between going out to this remote country road in the middle of the place that was in the heart of the Bible belt, that will still suffer from economic instability and going on seeing either a light or maybe encountering the devil was a really great metaphor and a foundation for our particular project about the Ozarks.

LS: Yes, I just add to that we were both drawn to return to the Ozarks, in part because of a frustration with the way those places are depicted in media. And so we were trying to think of a different kind of way to make work about these places that I think are really fault victim to a lot of storytellers coming from the outside areas, bringing in ideas what they think the Ozarks is. In our country, we really are particularly in a moment of a lot of divisions between rural America urban areas and I think both rural America and urban America are looking at each other with a lot of misinformation, misunderstanding, narrow ideas of who the people are in those places and what is life like. So, it was important for us to think of how do we use the stories that are coming from this place not the stories had implose on this place as a framework for our project and that was where interesting folklore began.

What are the people on that road truly looking for? What is the role of mystery in our lives?

LS: Well, what I thought about that the first time we went out there was that we didn’t know if the place was gonna be totally abandoned, nothing there, no one there and, I mean, there really wasn’t anything there but the first time we were showed up it was like a Friday night in the summer and it was a crowded road, there were cars parked along the side of the road and people were just standing out in this road in the dark, looking for this light and I thought it was really interesting how this is something that was ongoing, something that is really still part of the community. So, we spend a lot of time just standing out, just talking to people about this and that, about why they were there, what they are looking for. And I think it’s nice to have an experience in a place like that where there’s not a lot of parks or things like that. That’s just getting out, not going to like wall mark, not going to a church or some place like that but just going at some place where you can get together with other people or just get out of your house and have this kind of communal and mediating experience in nature. But with that kind of extra bit about seeing something possibly magical, it just really did seem to bring out a spiritual side in the people that we talk to. We were really surprised by the types of conversation that we were having, the depth of conversations people were talking about: life, death, souls, very metaphysical. It makes me think a lot about why is this place still around, usually nothing care, what is the function of it. And I think we still need a little bit of the unexplained in our lives and it’s a place where if you grow up there, if you got there your all life, like a lot o people are, there is not a lot that feels new and surprising and we really need that, I’ve been thinking about that a lot this last year at home with my family… And for us, for the grown-ups, it wasn’t exactly a time of discovering excitement, you know, it was like stuck in our house seem everyday. But we were there with this person that is still learning about the world and that just wake up excited and engaged and I think as an adult you have to hang on to some of that things can be surprising, wonders and beautiful. So, I felt like that was really important and beyond the nature of the story, that there is that beautiful light but also the devil, seem really interesting to me like it gave people this way to talk about the unpredictability of life. You know, you go to this place and you don’t know if you are gonna get this beautiful experience or damnation, I mean it’s really like a metaphor for growing up in a place without a lot of options, without a lot of second chances and I do think the stories that we tell, they really shape us as a community, they kind define us as a community and they say a lot about what our values are, what our desires are and what it is that we’re trying to understand that’s difficult to understand. Antone and I we’re having conversations with like a guy from like a mechanic shop, a restaurant manager, this kind of people that are living around, walking around town, living there that if you talk to them, if we met them any other circumstance we wouldn’t just had, just kind of your everyday small talk but meeting them on this road things got deep, really fast. That was really interesting to me.

AD: Go after what you’re saying. I think there’s so much importance in just the human experience of looking at the world with like some form of enchantments and that’s what we sure noticed with people going out to the road. There’s still this ability to look at the world and see this been enchanted and mysterious and a sort of wonderful in this way we don’t experience it in the day to day life. We can look at the world occasionally has been enchanted then we have the possibility and becoming more engaged with it and maybe more engaged with the environment that we’re in, caring more about the environment that we’re in and caring more about the people because that’s what that kind of experience provides for individuals and communities. And I also think it’s important to realize this story of going out to the Devil’s Promenade and possibly seeing the Ozark light or possibly encountering the devil at night. That story is over a hundred years old at this point and well before movie theatres were in the local communities, in the local towns of that area, and so it was a form of entertainment to one degree but it was also a form of having the community come together and participate together in this community activity of going out to see this, you know, phenomenon or experience it themselves. And that has stayed with this specific community for over a hundred years and I think that says a lot about the power of stories and what they can do and how they can shape us and how they can bound us together as people.

Publishing could be seen as an anachronistic practice. Why do you think it could still have a role in shaping contemporary visual culture? Is printing a way to return images to where they belong?

LS: Well, first of all, I mean, images belong everywhere and whether that’s my opinion or not they’re everywhere and I don’t think that’s gonna be changing. I think that is one of the reasons why the photo book is really important, when you have this society of images where they’re so malleable and easily transferable it can be hard for an artist to kind of corral their work into a container that really fully expresses their ideas about a project. I think that’s really important, that means a lot to our work, we are not the kind of artists that make a single image that conveys all of our ideas, it’s really about the sequence, the connection between images and texts and ephemeral and design and how all these things come together to create a morse of experience that’s something that really drives us as far as artists. I mean, we’re really always thinking about the book from day one.

AD: Yes and we actually use to both work at photo wide book stores, so we’ve been involved in photo books, in setting photo books for quite some time and for us like Laura said we make work that is important to be seen in a sequence, it’s their long form near the projects. We also work in different genres of photography so we’re using different types of images, both archival images, our own images, images that are performed and some that are documentary, and to be able to put that into the book form and make connections among all of these players that we’re really working with, it seems to be a really great container for our projects, it’s something that we can create and provide for a viewer who can really focus on the work in a quiet and sort of meditated state and really be able to look at the work and make those kinds of connections that we want people to see. It’s about as much of control we can have with our work, what goes out into the public and so for us the photo book is just kind of this form that seems to have infinite possibilities with the way that we can communicate our ideas and our projects.

Credits:

Featuring: Antone Dolezal and Lara Shipley

Curated by Robin Sara Stauder

Editor: Alice De Santis and Nicole Salotti

Visual: C41.eu